полная версия

полная версияMemoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Volume I., Part 2

The admiral stated that he had met a force of infantry and artillery which gave him great trouble by killing the men who had to expose themselves outside the iron armor to shove off the bows of the boats, which had so little headway that they would not steer. He begged me to come to his rescue as quickly as possible. Giles A. Smith had only about eight hundred men with him, but I ordered him to start up Deer Creek at once, crossing to the east side by an old bridge at Hill's plantation, which we had repaired for the purpose; to work his way up to the gunboat, fleet, and to report to the admiral that I would come, up with every man I could raise as soon as possible. I was almost alone at Hill's, but took a canoe, paddled down Black Bayou to the gunboat Price, and there, luckily, found the Silver wave with a load of men just arrived from twin's plantation. Taking some of the parties who were at work along the bayou into an empty coal-barge, we tugged it up by a navy-tug, followed by the Silver Wave, crashing through the trees, carrying away pilot-house, smoke-stacks, and every thing above-deck; but the captain (McMillan, of Pittsburg) was a brave fellow, and realized the necessity. The night was absolutely black, and we could only make two and a half of the four miles. We then disembarked, and marched through the canebrake, carrying lighted candles in our hands, till we got into the open cotton-fields at Hill's plantation, where we lay down for a few hours' rest. These men were a part of Giles A. Smith's brigade, and part belonged to the brigade of T. Bilby Smith, the senior officer present being Lieutenant-Colonel Rice, Fifty-fourth Ohio, an excellent young officer. We had no horses.

On Sunday morning, March 21st, as soon as daylight appeared, we started, following the same route which Giles A. Smith had taken the day before; the battalion of the Thirteenth United States Regulars, Major Chase, in the lead. We could hear Porter's guns, and knew that moments were precious. Being on foot myself, no man could complain, and we generally went at the double-quick, with occasional rests. The road lay along Deer Creek, passing several plantations; and occasionally, at the bends, it crossed the swamp, where the water came above my hips. The smaller drummer-boys had to carry their drums on their heads, and most of the men slang their cartridge-boxes around their necks. The soldiers generally were glad to have their general and field officers afoot, but we gave them a fair specimen of marching, accomplishing about twenty-one miles by noon. Of course, our speed was accelerated by the sounds of the navy-guns, which became more and more distinct, though we could see nothing. At a plantation near some Indian mounds we met a detachment of the Eighth Missouri, that had been up to the fleet, and had been sent down as a picket to prevent any obstructions below. This picket reported that Admiral Porter had found Deer Creek badly obstructed, had turned back; that there was a rebel force beyond the fleet, with some six-pounders, and nothing between us and the fleet. So I sat down on the door-sill of a cabin to rest, but had not been seated ten minutes when, in the wood just ahead, not three hundred yards off, I heard quick and rapid firing of musketry. Jumping up, I ran up the road, and found Lieutenant-Colonel Rice, who said the head of his column had struck a small force of rebels with a working gang of negroes, provided with axes, who on the first fire had broken and run back into the swamp. I ordered Rice to deploy his brigade, his left on the road, and extending as far into the swamp as the ground would permit, and then to sweep forward until he uncovered the gunboats. The movement was rapid and well executed, and we soon came to some large cotton-fields and could see our gunboats in Deer Creek, occasionally firing a heavy eight-inch gun across the cotton field into the swamp behind. About that time Major Kirby, of the Eighth Missouri, galloped down the road on a horse he had picked up the night before, and met me. He explained the situation of affairs, and offered me his horse. I got on bareback, and rode up the levee, the sailors coming out of their iron-clads and cheering most vociferously as I rode by, and as our men swept forward across the cotton-field in full view. I soon found Admiral Porter, who was on the deck of one of his iron-clads, with a shield made of the section of a smoke-stack, and I doubt if he was ever more glad to meet a friend than he was to see me. He explained that he had almost reached the Rolling Fork, when the woods became full of sharp-shooters, who, taking advantage of trees, stumps, and the levee, would shoot down every man that poked his nose outside the protection of their armor; so that he could not handle his clumsy boats in the narrow channel. The rebels had evidently dispatched a force from Haines's Bluff up the Sunflower to the Rolling Fork, had anticipated the movement of Admiral Porter's fleet, and had completely obstructed the channel of the upper part of Deer Creek by felling trees into it, so that further progress in that direction was simply impossible. It also happened that, at the instant of my arrival, a party of about four hundred rebels, armed and supplied with axes, had passed around the fleet and had got below it, intending in like manner to block up the channel by the felling of trees, so as to cut off retreat. This was the force we had struck so opportunely at the time before described. I inquired of Admiral Porter what he proposed to do, and he said he wanted to get out of that scrape as quickly as possible. He was actually working back when I met him, and, as we then had a sufficient force to cover his movement completely, he continued to back down Deer Creek. He informed me at one time things looked so critical that he had made up his mind to blow up the gunboats, and to escape with his men through the swamp to the Mississippi River. There being no longer any sharp-shooters to bother the sailors, they made good progress; still, it took three full days for the fleet to back out of Deer Creek into Black Bayou, at Hill's plantation, whence Admiral Porter proceeded to his post at the month of the Yazoo, leaving Captain Owen in command of the fleet. I reported the facts to General Grant, who was sadly disappointed at the failure of the fleet to get through to the Yazoo above Haines's Bluff, and ordered us all to resume our camps at Young's Point. We accordingly steamed down, and regained our camps on the 27th. As this expedition up Deer Creek was but one of many efforts to secure a footing from which to operate against Vicksburg, I add the report of Brigadier-General Giles A. Smith, who was the first to reach the fleet:

HEADQUARTERS FIRST BRIGADE, SECOND DIVISION

FIFTEENTH ARMY CORPS, YOUNGS POINT, LOUISIANA,

March 28, 1863

Captain L. M. DAYTON, Assistant Adjutant-General.

CAPTAIN: I have the honor to report the movements of the First Brigade in the expedition up Steele's Bayou, Black Bayou, and Deer Creek. The Sixth Missouri and One Hundred and Sixteenth Illinois regiments embarked at the month of Muddy Bayou on the evening of Thursday, the 18th of March, and proceeded up Steele's Bayou to the month of Black; thence up Black Bayou to Hill's plantation, at its junction with Deer Creek, where we arrived on Friday at four o'clock p.m., and joined the Eighth Missouri, Lieutenant-Colonel Coleman commanding, which had arrived at that point two days before. General Sherman had also established his headquarters there, having preceded the Eighth Missouri in a tug, with no other escort than two or three of his staff, reconnoitring all the different bayous and branches, thereby greatly facilitating the movements of the troops, but at the same time exposing himself beyond precedent in a commanding general. At three o'clock of Saturday morning, the 20th instant, General Sherman having received a communication from Admiral Porter at the mouth of Rolling Fork, asking for a speedy cooperation of the land forces with his fleet, I was ordered by General Sherman to be ready, with all the available force at that point, to accompany him to his relief; but before starting it was arranged that I should proceed with the force at hand (eight hundred men), while he remained, again entirely unprotected, to hurry up the troops expected to arrive that night, consisting of the Thirteenth Infantry and One Hundred and Thirteenth Illinois Volunteers, completing my brigade, and the Second Brigade, Colonel T. Kilby Smith commanding.

This, as the sequel showed; proved a very wise measure, and resulted in the safety of the whole fleet. At daybreak we were in motion, with a regular guide. We had proceeded but about six miles, when we found the enemy had been very busy felling trees to obstruct the creek.

All the negroes along the route had been notified to be ready at night fall to continue the work. To prevent this as much as possible, I ordered all able-bodied negroes to be taken along, and warned some of the principal inhabitants that they would be held responsible for any more obstructions being placed across the creek. We reached the admiral about four o'clock p.m., with no opposition save my advance-guard (Company A, Sixth Missouri) being fired into from the opposite side of the creek, killing one man, and slightly wounding another; having no way of crossing, we had to content ourselves with driving them beyond musket-range. Proceeding with as little loss of time as possible, I found the fleet obstructed in front by fallen trees, in rear by a sunken coal-barge, and surrounded, by a large force of rebels with an abundant supply of artillery, but wisely keeping their main force out of range of the admiral's guns. Every tree and stump covered a sharp-shooter, ready to pick off any luckless marine who showed his head above-decks, and entirely preventing the working-parties from removing obstructions.

In pursuance of orders from General Sherman, I reported to Admiral Porter for orders, who turned over to me all the land-forces in his fleet (about one hundred and fifty men), together with two howitzers, and I was instructed by him to retain a sufficient force to clear out the sharp-shooters, and to distribute the remainder along the creek for six or seven miles below, to prevent any more obstructions being placed in it during the night. This was speedily arranged, our skirmishers capturing three prisoners. Immediate steps were now taken to remove the coal-barge, which was accomplished about daylight on Sunday morning, when the fleet moved back toward Black Bayou. By three o'clock p.m. we had only made about six miles, owing to the large number of trees to be removed; at this point, where our progress was very slow, we discovered a long line of the enemy filing along the edge of the woods, and taking position on the creek below us, and about one mile ahead of our advance. Shortly after, they opened fire on the gunboats from batteries behind the cavalry and infantry. The boats not only replied to the batteries, which they soon silenced, but poured a destructive fire into their lines. Heavy skirmishing was also heard in our front, supposed to be by three companies from the Sixth and Eighth Missouri, whose position, taken the previous night to guard the creek, was beyond the point reached by the enemy, and consequently liable to be cut off or captured. Captain Owen, of the Louisville, the leading boat, made every effort to go through the obstructions and aid in the rescuing of the men. I ordered Major Kirby, with four companies of the Sixth Missouri, forward, with two companies deployed. He soon met General Sherman, with the Thirteenth Infantry and One Hundred and Thirteenth Illinois, driving the enemy before them, and opening communication along the creek with the gunboats. Instead of our three companies referred to as engaging the enemy, General Sherman had arrived at a very opportune moment with the two regiments mentioned above, and the Second Brigade. The enemy, not expecting an attack from that quarter, after some hot skirmishing, retreated. General Sherman immediately ordered the Thirteenth Infantry and One Hundred and Thirteenth Illinois to pursue; but, after following their trace for about two miles, they were recalled.

We continued our march for about two miles, when we bivouacked for the night. Early on Monday morning (March 22d) we continued our march, but owing to the slow progress of the gunboats did not reach Hill's plantation until Tuesday, the 23d instant, where we remained until the 25th; we then reembarked, and arrived at Young's Point on Friday, the 27th instant.

Below you will find a list of casualties. Very respectfully,

Giles A. SMITH, Colonel Eighth Missouri, commanding First Brigade.

P. S.-I forgot to state above that the Thirteenth Infantry and One Hundred and Thirteenth Illinois being under the immediate command of General Sherman, he can mention them as their conduct deserves.

On the 3d of April, a division of troops, commanded by Brigadier-General J. M. Tuttle, was assigned to my corps, and was designated the Third Division; and, on the 4th of April, Brigadier-General D. Stuart was relieved from the command of the Second Division, to which Major-General Frank P. Blair was appointed by an order from General Grant's headquarters. Stuart had been with me from the time we were at Benton Barracks, in command of the Fifty-fifth Illinois, then of a brigade, and finally of a division; but he had failed in seeking a confirmation by the Senate to his nomination as brigadier-general, by reason of some old affair at Chicago, and, having resigned his commission as colonel, he was out of service. I esteemed him very highly, and was actually mortified that the service should thus be deprived of so excellent and gallant an officer. He afterward settled in New Orleans as a lawyer, and died about 1867 or 1868.

On the 6th of April, my command, the Fifteenth Corps, was composed of three divisions:

The First Division, commanded by Major-General Fred Steele; and his three brigades by Colonel Manter, Colonel Charles R. Wood, and Brigadier-General John M. Thayer.

The Second Division, commanded by Major-General Frank P. Blair; and his three brigades by Colonel Giles A. Smith, Colonel Thomas Gilby Smith, and Brigadier-General Hugh Ewing.

The Third Division, commanded by Brigadier-General J. M. Tuttle; and his three brigades by Brigadier-General R. P. Buckland, Colonel J. A. Mower, and Brigadier-General John E. Smith.

My own staff then embraced: Dayton, McCoy, and Hill, aides; J. H. Hammond, assistant adjutant-general; Sanger, inspector-general; McFeeley, commissary; J. Condit Smith, quartermaster; Charles McMillan, medical director; Ezra Taylor, chief of artillery; Jno. C. Neely, ordnance-officer; Jenney and Pitzman, engineers.

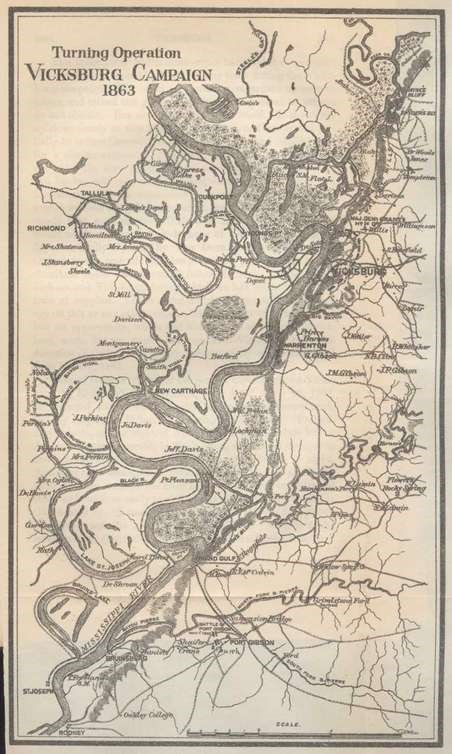

By this time it had become thoroughly demonstrated that we could not divert the main river Mississippi, or get practicable access to the east bank of the Yazoo, in the rear of Vicksburg, by any of the passes; and we were all in the habit of discussing the various chances of the future. General Grant's headquarters were at Milliken's Bend, in tents, and his army was strung along the river all the way from Young's Point up to Lake Providence, at least sixty miles. I had always contended that the best way to take Vicksburg was to resume the movement which had been so well begun the previous November, viz., for the main army to march by land down the country inland of the Mississippi River; while the gunboat-fleet and a minor land-force should threaten Vicksburg on its river-front.

I reasoned that, with the large force then subject to General Grant's orders-viz., four army corps—he could easily resume the movement from Memphis, by way of Oxford and Grenada, to Jackson, Mississippi, or down the ridge between the Yazoo and Big Black; but General Grant would not, for reasons other than military, take any course which looked like, a step backward; and he himself concluded on the river movement below Vicksburg, so as to appear like connecting with General Banks, who at the same time was besieging Port Hudson from the direction of New Orleans.

Preliminary orders had already been given, looking to the digging of a canal, to connect the river at Duckport with Willow Bayou, back of Milliken's Bend, so as to form a channel for the conveyance of supplies, by way of Richmond, to New Carthage; and several steam dredge-boats had come from the upper rivers to assist in the work. One day early in April, I was up at General Grant's headquarters, and we talked over all these things with absolute freedom. Charles A. Dana, Assistant Secretary of War, was there, and Wilson, Rawlins, Frank Blair, McPherson, etc. We all knew, what was notorious, that General McClernand was still intriguing against General Grant, in hopes to regain the command of the whole expedition, and that others were raising a clamor against General Grant in the news papers at the North. Even Mr. Lincoln and General Halleck seemed to be shaken; but at no instant of time did we (his personal friends) slacken in our loyalty to him. One night, after such a discussion, and believing that General McClernand had no real plan of action shaped in his mind, I wrote my letter of April 8, 1863, to Colonel Rawlins, which letter is embraced in full at page 616 of Badeau's book, and which I now reproduce here:

HEADQUARTERS FIFTEENTH ARMY CORPS,

CAMP NEAR VICKSBURG, April 8,1868.

Colonel J. A. RAWLINS, Assistant Adjutant-General to General GRANT.

SIR: I would most respectfully suggest (for reasons which I will not name) that General Grant call on his corps commanders for their opinions, concise and positive, on the best general plan of a campaign. Unless this be done, there are men who will, in any result falling below the popular standard, claim that their advice was unheeded, and that fatal consequence resulted therefrom. My own opinions are:

First. That the Army of the Tennessee is now far in advance of the other grand armies of the United States.

Second. That a corps from Missouri should forthwith be moved from St. Louis to the vicinity of Little Rock, Arkansas; supplies collected there while the river is full, and land communication with Memphis opened via Des Arc on the White, and Madison on the St. Francis River.

Third. That as much of the Yazoo Pass, Coldwater, and Tallahatchie Rivers, as can be gained and fortified, be held, and the main army be transported thither by land and water; that the road back to Memphis be secured and reopened, and, as soon as the waters subside, Grenada be attacked, and the swamp-road across to Helena be patrolled by cavalry.

Fourth. That the line of the Yalabusha be the base from which to operate against the points where the Mississippi Central crosses Big Black, above Canton; and, lastly, where the Vicksburg & Jackson Railroad crosses the same river (Big Black). The capture of Vicksburg would result.

Fifth. That a minor force be left in this vicinity, not to exceed ten thousand men, with only enough steamboats to float and transport them to any desired point; this force to be held always near enough to act with the gunboats when the main army is known to be near Vicksburg—Haines's Bluff or Yazoo City.

Sixth. I do doubt the capacity of Willow Bayou (which I estimate to be fifty miles long and very tortuous) as a military channel, to supply an army large enough to operate against Jackson, Mississippi, or the Black River Bridge; and such a channel will be very vulnerable to a force coming from the west, which we must expect. Yet this canal will be most useful as the way to convey coals and supplies to a fleet that should navigate the lower reach of the Mississippi between Vicksburg and the Red River.

Seventh. The chief reason for operating solely by water was the season of the year and high water in the Tallahatchie and Yalabusha Rivers. The spring is now here, and soon these streams will be no serious obstacle, save in the ambuscades of the forest, and whatever works the enemy may have erected at or near Grenada. North Mississippi is too valuable for us to allow the enemy to hold it and make crops this year.

I make these suggestions, with the request that General Grant will read them and give them, as I know he will, a share of his thoughts. I would prefer that he should not answer this letter, but merely give it as much or as little weight as it deserves. Whatever plan of action he may adopt will receive from me the same zealous cooperation and energetic support as though conceived by myself. I do not believe General Banks will make any serious attack on Port Hudson this spring. I am, etc.,

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General.

This is the letter which some critics have styled a "protest." We never had a council of war at any time during the Vicksburg campaign. We often met casually, regardless of rank or power, and talked and gossiped of things in general, as officers do and should. But my letter speaks for itself—it shows my opinions clearly at that stage of the game, and was meant partially to induce General Grant to call on General McClernand for a similar expression of opinion, but, so far as I know, he did not. He went on quietly to work out his own designs; and he has told me, since the war, that had we possessed in December, 1862, the experience of marching and maintaining armies without a regular base, which we afterward acquired, he would have gone on from Oxford as first contemplated, and would not have turned back because of the destruction of his depot at Holly Springs by Van Dorn. The distance from Oxford to the rear of Vicksburg is little greater than by the circuitous route we afterward followed, from Bruinsburg to Jackson and Vicksburg, during which we had neither depot nor train of supplies. I have never criticised General Grant's strategy on this or any other occasion, but I thought then that he had lost an opportunity, which cost him and us six months' extra-hard work, for we might have captured Vicksburg from the direction of Oxford in January, quite as easily as was afterward done in July, 1863.

General Grant's orders for the general movement past Vicksburg, by Richmond and Carthage, were dated April 20, 1863. McClernand was to lead off with his corps, McPherson next, and my corps (the Fifteenth) to bring up the rear. Preliminary thereto, on the night of April 16th, seven iron-clads led by Admiral Porter in person, in the Benton, with three transports, and ten barges in tow, ran the Vicksburg batteries by night. Anticipating a scene, I had four yawl-boats hauled across the swamp, to the reach of the river below Vicksburg, and manned them with soldiers, ready to pick up any of the disabled wrecks as they floated by. I was out in the stream when the fleet passed Vicksburg, and the scene was truly sublime. As soon as the rebel gunners detected the Benton, which was in the lead, they opened on her, and on the others in succession, with shot and shell; houses on the Vicksburg side and on the opposite shore were set on fire, which lighted up the whole river; and the roar of cannon, the bursting of shells, and finally the burning of the Henry Clay, drifting with the current, made up a picture of the terrible not often seen. Each gunboat returned the fire as she passed the town, while the transports hugged the opposite shore. When the Benton had got abreast of us, I pulled off to her, boarded, had a few words with Admiral Porter, and as she was drifting rapidly toward the lower batteries at Warrenton, I left, and pulled back toward the shore, meeting the gunboat Tuscumbia towing the transport Forest Queen into the bank out of the range of fire. The Forest Queen, Captain Conway, had been my flag-boat up the Arkansas, and for some time after, and I was very friendly with her officers. This was the only transport whose captain would not receive volunteers as a crew, but her own officers and crew stuck to their boat, and carried her safely below the Vicksburg batteries, and afterward rendered splendid service in ferrying troops across the river at Grand Gulf and Bruinsburg. In passing Vicksburg, she was damaged in the hull and had a steam-pipe cut away, but this was soon repaired. The Henry Clay was set on fire by bursting shells, and burned up; one of my yawls picked up her pilot floating on a piece of wreck, and the bulk of her crew escaped in their own yawl-boat to the shore above. The Silver Wave, Captain McMillan, the same that was with us up Steele's Bayou, passed safely, and she also rendered good service afterward.