полная версия

полная версияMemoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Volume II., Part 4

We have a right to, use any sort of machinery to produce military results; and it is the commonest thing for military commanders to use the civil governments in actual existence as a means to an end. I do believe we could and can use the present State governments lawfully, constitutionally, and as the very best possible means to produce the object desired, viz., entire and complete submission to the lawful authority of the United States.

As to punishment for past crimes, that is for the judiciary, and can in no manner of way be disturbed by our acts; and, so far as I can, I will use my influence that rebels shall suffer all the personal punishment prescribed by law, as also the civil liabilities arising from their past acts.

What we now want is the new form of law by which common men may regain the positions of industry, so long disturbed by the war.

I now apprehend that the rebel armies will disperse; and, instead of dealing with six or seven States, we will have to deal with numberless bands of desperadoes, headed by such men as Mosby, Forrest, Red Jackson, and others, who know not and care not for danger and its consequences.

I am, with great respect, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General commanding.

HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI

IN THE FIELD, RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, April 25, 1865.

Hon. E. M. STANTON, Secretary of War, Washington.

DEAR SIR: I have been furnished a copy of your letter of April 21st to General Grant, signifying your disapproval of the terms on which General Johnston proposed to disarm and disperse the insurgents, on condition of amnesty, etc. I admit my folly in embracing in a military convention any civil matters; but, unfortunately, such is the nature of our situation that they seem inextricably united, and I understood from you at Savannah that the financial state of the country demanded military success, and would warrant a little bending to policy.

When I had my conference with General Johnston I had the public examples before me of General Grant's terms to Lee's army, and General Weitzel's invitation to the Virginia Legislature to assemble at Richmond.

I still believe the General Government of the United States has made a mistake; but that is none of my business–mine is a different task; and I had flattered myself that, by four years of patient, unremitting, and successful labor, I deserved no reminder such as is contained in the last paragraph of your letter to General Grant. You may assure the President that I heed his suggestion. I am truly, etc.,

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General commanding.

On the same day, but later, I received an answer from General Johnston, agreeing to meet me again at Bennett's house the next day, April 26th, at noon. He did not even know that General Grant was in Raleigh.

General Grant advised me to meet him, and to accept his surrender on the same terms as his with General Lee; and on the 26th I again went up to Durham's Station by rail, and rode out to Bennett's house, where we again met, and General Johnston, without hesitation, agreed to, and we executed, the following final terms:

Terms of a Military Convention, entered into this 26th day of April, 1865, at Bennett's House, near Durham's Station., North Carolina, between General JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON, commanding the Confederate Army, and Major-General W. T. SHERMAN, commanding the United States Army in North Carolina:

1. All acts of war on the part of the troops under General Johnston's command to cease from this date.

2. All arms and public property to be deposited at Greensboro', and delivered to an ordnance-officer of the United States Army.

3. Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate; one copy to be retained by the commander of the troops, and the other to be given to an officer to be designated by General Sherman. Each officer and man to give his individual obligation in writing not to take up arms against the Government of the United States, until properly released from this obligation.

4. The side-arms of officers, and their private horses and baggage, to be retained by them.

5. This being done, all the officers and men will be permitted to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by the United States authorities, so long as they observe their obligation and the laws in force where they may reside.

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General, Commanding United States Forces in North Carolina.

J. E. JOHNSTON, General, Commanding Confederate States Forces in North Carolina.

Approved:

U. S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General.

I returned to Raleigh the same evening, and, at my request, General Grant wrote on these terms his approval, and then I thought the matter was surely at an end. He took the original copy, on the 27th returned to Newbern, and thence went back to Washington.

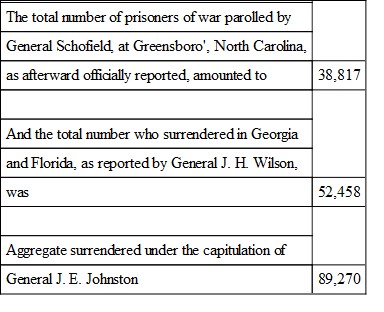

I immediately made all the orders necessary to carry into effect the terms of this convention, devolving on General Schofield the details of granting the parole and making the muster-rolls of prisoners, inventories of property, etc., of General Johnston's army at and about Greensboro', North Carolina, and on General Wilson the same duties in Georgia; but, thus far, I had been compelled to communicate with the latter through rebel sources, and General Wilson was necessarily confused by the conflict of orders and information. I deemed it of the utmost importance to establish for him a more reliable base of information and supply, and accordingly resolved to go in person to Savannah for that purpose. But, before starting, I received a New York Times, of April 24th, containing the following extraordinary communications:

[First Bulletin]

WAR DEPARTMENT WASHINGTON, April 22, 1885.

Yesterday evening a bearer of dispatches arrived from General Sherman. An agreement for a suspension of hostilities, and a memorandum of what is called a basis for peace, had been entered into on the 18th inst. by General Sherman, with the rebel General Johnston. Brigadier-General Breckenridge was present at the conference.

A cabinet meeting was held at eight o'clock in the evening, at which the action of General Sherman was disapproved by the President, by the Secretary of War, by General Grant, and by every member of the cabinet. General Sherman was ordered to resume hostilities immediately, and was directed that the instructions given by the late President, in the following telegram, which was penned by Mr. Lincoln himself, at the Capitol, on the night of the 3d of March, were approved by President Andrew Johnson, and were reiterated to govern the action of military commanders.

On the night of the 3d of March, while President Lincoln and his cabinet were at the Capitol, a telegram from General Grant was brought to the Secretary of War, informing him that General Lee had requested an interview or conference, to make an arrangement for terms of peace. The letter of General Lee was published in a letter to Davis and to the rebel Congress. General Grant's telegram was submitted to Mr. Lincoln, who, after pondering a few minutes, took up his pen and wrote with his own hand the following reply, which he submitted to the Secretary of State and Secretary of War. It was then dated, addressed, and signed, by the Secretary of War, and telegraphed to General Grant:

WASHINGTON, March 3, 1865-12 P.M.

Lieutenant-General GRANT:

The President directs me to say to you that he wishes you to have no conference with General Lee, unless it be for the capitulation of General Lee's army, or on some minor or purely military matter. He instructs me to say that you are not to decide, discuss, or confer upon any political questions. Such questions the President holds in his own hands, and will submit them to no military conferences or conventions.

Meantime you are to press to the utmost your military advantages.

EDWIN M. STANTON, Secretary of War.

The orders of General Sherman to General Stoneman to withdraw from Salisbury and join him will probably open the way for Davis to escape to Mexico or Europe with his plunder, which is reported to be very large, including not only the plunder of the Richmond banks, but previous accumulations.

A dispatch received by this department from Richmond says: "It is stated here, by respectable parties, that the amount of specie taken south by Jeff. Davis and his partisans is very large, including not only the plunder of the Richmond banks, but previous accumulations. They hope, it is said, to make terms with General Sherman, or some other commander, by which they will be permitted, with their effects, including this gold plunder, to go to Mexico or Europe. Johnston's negotiations look to this end."

After the cabinet meeting last night, General Grant started for North Carolina, to direct operations against Johnston's army.

EDWIN M. STANTON, Secretary of War.

Here followed the terms, and Mr. Stanton's ten reasons for rejecting them.

The publication of this bulletin by authority was an outrage on me, for Mr. Stanton had failed to communicate to me in advance, as was his duty, the purpose of the Administration to limit our negotiations to purely military matters; but, on the contrary, at Savannah he had authorized me to control all matters, civil and military.

By this bulletin, he implied that I had previously been furnished with a copy of his dispatch of March 3d to General Grant, which was not so; and he gave warrant to the impression, which was sown broadcast, that I might be bribed by banker's gold to permit Davis to escape. Under the influence of this, I wrote General Grant the following letter of April 28th, which has been published in the Proceedings of the Committee on the Conduct of the War.

I regarded this bulletin of Mr. Stanton as a personal and official insult, which I afterward publicly resented.

HEADQUARTERS MILITARY DIVISION OF THE MISSISSIPPI

IN THE FIELD, RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, April 28,1865.

Lieutenant-General U. S. GRANT, General-in-Chief, Washington, D. C.

GENERAL: Since you left me yesterday, I have seen the New York Times of the 24th, containing a budget of military news, authenticated by the signature of the Secretary of War, Hon. E. M. Stanton, which is grouped in such a way as to give the public very erroneous impressions. It embraces a copy of the basis of agreement between myself and General Johnston, of April 18th, with comments, which it will be time enough to discuss two or three years hence, after the Government has experimented a little more in the machinery by which power reaches the scattered people of the vast country known as the "South."

In the mean time, however, I did think that my rank (if not past services) entitled me at least to trust that the Secretary of War would keep secret what was communicated for the use of none but the cabinet, until further inquiry could be made, instead of giving publicity to it along with documents which I never saw, and drawing therefrom inferences wide of the truth. I never saw or had furnished me a copy of President Lincoln's dispatch to you of the 3d of March, nor did Mr. Stanton or any human being ever convey to me its substance, or any thing like it. On the contrary, I had seen General Weitzel's invitation to the Virginia Legislature, made in Mr. Lincoln's very presence, and failed to discover any other official hint of a plan of reconstruction, or any ideas calculated to allay the fears of the people of the South, after the destruction of their armies and civil authorities would leave them without any government whatever.

We should not drive a people into anarchy, and it is simply impossible for our military power to reach all the masses of their unhappy country.

I confess I did not desire to drive General Johnston's army into bands of armed men, going about without purpose, and capable only of infinite mischief. But you saw, on your arrival here, that I had my army so disposed that his escape was only possible in a disorganized shape; and as you did not choose to "direct military operations in this quarter," I inferred that you were satisfied with the military situation; at all events, the instant I learned what was proper enough, the disapproval of the President, I acted in such a manner as to compel the surrender of General Johnston's whole army on the same terms which you had prescribed to General Lee's army, when you had it surrounded and in your absolute power.

Mr. Stanton, in stating that my orders to General Stoneman were likely to result in the escape of "Mr. Davis to Mexico or Europe," is in deep error. General Stoneman was not at "Salisbury," but had gone back to "Statesville." Davis was between us, and therefore Stoneman was beyond him. By turning toward me he was approaching Davis, and, had he joined me as ordered, I would have had a mounted force greatly needed for Davis's capture, and for other purposes. Even now I don't know that Mr. Stanton wants Davis caught, and as my official papers, deemed sacred, are hastily published to the world, it will be imprudent for me to state what has been done in that regard.

As the editor of the Times has (it may be) logically and fairly drawn from this singular document the conclusion that I am insubordinate, I can only deny the intention.

I have never in my life questioned or disobeyed an order, though many and many a time have I risked my life, health, and reputation, in obeying orders, or even hints to execute plans and purposes, not to my liking. It is not fair to withhold from me the plans and policy of Government (if any there be), and expect me to guess at them; for facts and events appear quite different from different stand-points. For four years I have been in camp dealing with soldiers, and I can assure you that the conclusion at which the cabinet arrived with such singular unanimity differs from mine. I conferred freely with the best officers in this army as to the points involved in this controversy, and, strange to say, they were singularly unanimous in the other conclusion. They will learn with pain and amazement that I am deemed insubordinate, and wanting in commonsense; that I, who for four years have labored day and night, winter and summer, who have brought an army of seventy thousand men in magnificent condition across a country hitherto deemed impassable, and placed it just where it was wanted, on the day appointed, have brought discredit on our Government! I do not wish to boast of this, but I do say that it entitled me to the courtesy of being consulted, before publishing to the world a proposition rightfully submitted to higher authority for adjudication, and then accompanied by statements which invited the dogs of the press to be let loose upon me. It is true that non-combatants, men who sleep in comfort and security while we watch on the distant lines, are better able to judge than we poor soldiers, who rarely see a newspaper, hardly hear from our families, or stop long enough to draw our pay. I envy not the task of "reconstruction," and am delighted that the Secretary of War has relieved me of it.

As you did not undertake to assume the management of the affairs of this army, I infer that, on personal inspection, your mind arrived at a different conclusion from that of the Secretary of War. I will therefore go on to execute your orders to the conclusion, and, when done, will with intense satisfaction leave to the civil authorities the execution of the task of which they seem so jealous. But, as an honest man and soldier, I invite them to go back to Nashville and follow my path, for they will see some things and hear some things that may disturb their philosophy.

With sincere respect,

W. T. SHERMAN, Major-General commanding.

P. S.–As Mr. Stanton's most singular paper has been published, I demand that this also be made public, though I am in no manner responsible to the press, but to the law, and my proper superiors.

W. T. S., Major-General.

On the 28th I summoned all the army and corps commanders together at my quarters in the Governor's mansion at Raleigh, where every thing was explained to them, and all orders for the future were completed. Generals Schofield, Terry, and Kilpatrick, were to remain on duty in the Department of North Carolina, already commanded by General Schofield, and the right and left wings were ordered to march under their respective commanding generals North by easy stages to Richmond, Virginia, there to await my return from the South.

On the 29th of April, with a part of my personal staff, I proceeded by rail to Wilmington, North Carolina, where I found Generals Hawley and Potter, and the little steamer Russia, Captain Smith, awaiting me. After a short pause in Wilmington, we embarked, and proceeded down the coast to Port Royal and the Savannah River, which we reached on the 1st of May. There Captain Hoses, who had just come from General Wilson at Macon, met us, bearing letters for me and General Grant, in which General Wilson gave a brief summary of his operations up to date. He had marched from Eastport, Mississippi, five hundred miles in thirty days, took six thousand three hundred prisoners, twenty-three colors, and one hundred and fifty-six guns, defeating Forrest, scattering the militia, and destroying every railroad, iron establishment, and factory, in North Alabama and Georgia.

He spoke in the highest terms of his cavalry, as "cavalry," claiming that it could not be excelled, and he regarded his corps as a model for modern cavalry in organization, armament, and discipline. Its strength was given at thirteen thousand five hundred men and horses on reaching Macon. Of course I was extremely gratified at his just confidence, and saw that all he wanted for efficient action was a sure base of supply, so that he need no longer depend for clothing, ammunition, food, and forage, on the country, which, now that war had ceased, it was our solemn duty to protect, instead of plunder. I accordingly ordered the captured steamer Jeff. Davis to be loaded with stores, to proceed at once up the Savannah River to Augusta, with a small detachment of troops to occupy the arsenal, and to open communication with General Wilson at Macon; and on the next day, May 2d, this steamer was followed by another with a fall cargo of clothing, sugar, coffee, and bread, sent from Hilton Head by the department commander, General Gillmore, with a stronger guard commanded by General Molineux. Leaving to General Gillmore, who was present, and in whose department General Wilson was, to keep up the supplies at Augusta, and to facilitate as far as possible General Wilson's operations inland, I began my return on the 2d of May. We went into Charleston Harbor, passing the ruins of old Forts Moultrie and Sumter without landing. We reached the city of Charleston, which was held by part of the division of General John P. Hatch, the same that we had left at Pocotaligo. We walked the old familiar streets–Broad, King, Meeting, etc.–but desolation and ruin were everywhere. The heart of the city had been burned during the bombardment, and the rebel garrison at the time of its final evacuation had fired the railroad-depots, which fire had spread, and was only subdued by our troops after they had reached the city.

I inquired for many of my old friends, but they were dead or gone, and of them all I only saw a part of the family of Mrs. Pettigru. I doubt whether any city was ever more terribly punished than Charleston, but, as her people had for years been agitating for war and discord, and had finally inaugurated the civil war by an attack on the small and devoted garrison of Major Anderson, sent there by the General Government to defend them, the judgment of the world will be, that Charleston deserved the fate that befell her. Resuming our voyage, we passed into Cape Fear River by its mouth at Fort Caswell and Smithville, and out by the new channel at Fort Fisher, and reached Morehead City on the 4th of May. We found there the revenue-cutter Wayanda, on board of which were the Chief-Justice, Mr. Chase, and his daughter Nettie, now Mrs. Hoyt. The Chief-Justice at that moment was absent on a visit to Newbern, but came back the next day. Meantime, by means of the telegraph, I was again in correspondence with General Schofield at Raleigh. He had made great progress in paroling the officers and men of Johnston's army at Greensboro', but was embarrassed by the utter confusion and anarchy that had resulted from a want of understanding on many minor points, and on the political questions that had to be met at the instant. In order to facilitate the return to their homes of the Confederate officers and men, he had been forced to make with General Johnston the following supplemental terms, which were of course ratified and approved:

MILITARY CONVENTION OF APRIL 26, 1865.

SUPPLEMENTAL TERMS.

1. The field transportation to be loaned to the troops for their march to their homes, and for subsequent use in their industrial pursuits. Artillery-horses may be used in field-transportation, if necessary.

2. Each brigade or separate body to retain a number of arms equal to one-seventh of its effective strength, which, when the troops reach the capitals of their states, will be disposed of as the general commanding the department may direct.

3. Private horses, and other private property of both officers and men, to be retained by them.

4. The commanding general of the Military Division of West Mississippi, Major-General Canby, will be requested to give transportation by water, from Mobile or New Orleans, to the troops from Arkansas and Texas.

5. The obligations of officers and soldiers to be signed by their immediate commanders.

6. Naval forces within the limits of General Johnston's command to be included in the terms of this convention.

J. M. SCHOFIELD, Major-General,

Commanding United States Forces in North Carolina.

J. E. JOHNSTON, General,

Commanding Confederate States Forces in North Carolina.

On the morning of the 5th I also received from General Schofield this dispatch:

RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA, May 5, 1866.

To Major-General W: T. SHERMAN, Morehead City:

When General Grant was here, as you doubtless recollect, he said the lines (for trade and intercourse) had been extended to embrace this and other States south. The order, it seems, has been modified so as to include only Virginia and Tennessee. I think it would be an act of wisdom to open this State to trade at once.

I hope the Government will make known its policy as to the organs of State government without delay. Affairs must necessarily be in a very unsettled state until that is done. The people are now in a mood to accept almost anything which promises a definite settlement. "What is to be done with the freedmen?" is the question of all, and it is the all important question. It requires prompt and wise notion to prevent the negroes from becoming a huge elephant on our hands. If I am to govern this State, it is important for me to know it at once. If another is to be sent here, it cannot be done too soon, for he probably will undo the most that I shall have done. I shall be glad to hear from you fully, when you have time to write. I will send your message to General Wilson at once.

J. M. SCHOFIELD, Major-General.

I was utterly without instructions from any source on the points of General Schofield's inquiry, and under the existing state of facts could not even advise him, for by this time I was in possession of the second bulletin of Mr. Stanton, published in all the Northern papers, with comments that assumed that I was a common traitor and a public enemy; and high officials had even instructed my own subordinates to disobey my lawful orders. General Halleck, who had so long been in Washington as the chief of staff, had been sent on the 21st of April to Richmond, to command the armies of the Potomac and James, in place of General Grant, who had transferred his headquarters to the national capital, and he (General Halleck) was therefore in supreme command in Virginia, while my command over North Carolina had never been revoked or modified.

[Second Bulletin.]

WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, April 27 9.30 a.m.

To Major-General DIX:

The department has received the following dispatch from Major-General Halleck, commanding the Military Division of the James. Generals Canby and Thomas were instructed some days ago that Sherman's arrangements with Johnston were disapproved by the President, and they were ordered to disregard it and push the enemy in every direction.