полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Young. Wings and tail as in adult. Downy plumage of head and body ochraceous, with detached, rather distant, transverse bars of dusky. (12,062, Washington, D. C., May 20, 1859; C. Drexler.)

Hab. Eastern North America, south of Labrador; west to the Missouri; south through Atlantic region of Mexico to Costa Rica; Jamaica (Gosse).

Localities: (?) Oaxaca (Scl. 1859, 390; possibly var. arcticus); Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I. 222); Jamaica (Gosse, 23); Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 330, breeds); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 132).

Specimens from the regions indicated vary but little, the only two possessing differences of any note being one (58,747,30 ♂) from Southern Illinois, and one (33,218, San Jose; J. Carmiol) from Costa Rica. The first differs from all those from the eastern United States in much deeper and darker shades of color, the rufous predominant below, the legs and crissum being of quite a deep shade of this color; the transverse bars beneath are also very broad and pure black. This specimen is more like Audubon’s figure than any other, and may possibly represent the peculiar style of the Lower Mississippi region. The Costa Rica bird is remarkable for the predominance of the rufous on all parts of the plumage; the legs, however, are whitish, as in specimens from the Atlantic coast of the United States. These specimens cannot, however, be considered as anything else than merely local styles of the virginianus, var. virginianus.

Bubo virginianus, var. arcticus, SwainsWESTERN GREAT HORNED OWL? Strix wapacuthu, Gmel. Syst. Nat. 1789, p. 290. Strix (Bubo) arctica, Swains. F. B. A. II, 1831, 86. Heliaptex arcticus, Swains. Classif. Birds, I, 1837, 328; Ib. II, 217. Bubo virginianus arcticus, Cass. Birds N. Am. 1858, 50 (B. virginianus).—Blakiston, Ibis, III, 1861, 320. Bubo virginianus, var. arcticus, Coues, Key, 1872, 202. Bubo subarcticus, Hoy, P. A. N. S. VI, 1852, 211. Bubo virginianus pacificus, Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. 1854, and Birds N. Am. 1858 (B. virginianus, in part only). Bubo magellanicus, Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. 1854, 178 (not B. magellanicus of Lesson!). Bubo virginianus, Heerm. 34.—Kennerly, 20.—Coues, Prod. (P. A. N. S. 1866, 13).—Blakiston, Ibis, III, 1861, 320. ? Wapacuthu Owl, Pennant, Arctic Zoöl. 231.—Lath. Syn. Supp. I, 49.

Char. Pattern of coloration precisely like that of var. virginianus, but the general aspect much lighter and more grayish, caused by a greater prevalence of the lighter tints, and contraction of dark pencillings. The ochraceous much lighter and less rufous. Face soiled white, instead of deep dingy rufous.

♂ (No. 21,581, Camp Kootenay, Washington Territory, August 2, 1860). Wing, 14.00; tail, 8.60; culmen, 1.10; tarsus, 2.00. Tail and primaries each with the dark bands nine in number; legs and feet immaculate white. Wing-formula, 3, 2=4–5–1.

♀ (No. 10,574, Fort Tejon, California). Wing, 14.70; tail, 9.50; culmen, 1.10; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 2.00. Tail and primaries each with seven dark bands; legs transversely barred with dusky. Wing-formula, 3, 4, 2–5–1, 6.

Hab. Western region of North America, from the interior Arctic districts to the table-lands of Mexico. Wisconsin (Hoy); Northern Illinois (Pekin, Mus. Cambridge); Lower California; ? Orizaba, Mexico.

Localities: (?) Orizaba (Scl. P. Z. S. 1860, 253); Arizona (Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866, 49).

The above description covers the average characters of a light grayish race of the B. virginianus, which represents the other styles in the whole of the western and interior regions of the continent. Farther northward, in the interior of the fur countries, the plumage becomes lighter still, some Arctic specimens being almost as white as the Nyctea scandiaca. The B. arcticus of Swainson was founded upon a specimen of this kind, and it is our strong opinion that the Wapecuthu Owl of Pennant (Strix wapecuthu, Gmel.) was nothing else than a similar individual, which had accidentally lost the ear-tufts, since there is no other discrepancy in the original description. The failure to mention ear-tufts, too, may have been merely a neglect on the part of the describer.

Bubo virginianus, var. pacificus, CassBubo virginianus pacificus, Cassin, Birds N. Am. 1858, 49. Bubo virginianus, var. pacificus, Coues, Key, 1872, 202. Bubo virginianus, Coop. & Suckley, P. R. Rept. XII, ii, 1860, 154.—Lord, Pr. R. A. S. IV, III (British Columbia). ? Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chicago Ac. I, 1869, 272 (Alaska).—? Finsch, Abh. Nat. III, 26 (Alaska).

Sp. Char. The opposite extreme from var. arcticus. The black shades predominating and the white mottling replaced by pale grayish; the form of the mottling above is less regularly transverse, being oblique or longitudinal, and more in blotches than in the other styles. The primary coverts are plain black; the primaries are mottled gray and plain black. On the tail the mottling is very dark, the lighter markings on the middle feathers being thrown into longitudinal splashes. Beneath, the black bars are nearly as wide as the white, fully double their width in var. arcticus. The legs are always thickly barred. The lining of the wings is heavily barred with black. Face dull grayish, barred with dusky; ear-tufts almost wholly black.

♂ (45,842, Sitka, Alaska, November, 1866; Ferd. Bischoff). Wing-formula, 3, 2=4–5–1, 6. Wing, 14.00; tail, 8.00; culmen, 1.10; tarsus, 2.05; middle toe, .95.

Face with obscure bars of black; ochraceous of the bases of the feathers is distinct. There are seven black spots on the primaries, eight on the tail; on the latter exceeding the paler in width.

♀ (27,075, Yukon River, mouth Porcupine, April 16, 1861; R. Kennicott). Wing-formula, 3, 2=4–5–1, 6. Wing, 16.00; tail, 9.80; culmen, 1.15; tarsus, 2.00. Eight black spots on primaries, seven on tail.

Hab. Pacific coast north of the Columbia; Labrador. A northern littoral form.

A specimen from Labrador (34,958, Fort Niscopec, H. Connolly) is an extreme example of this well-marked variety. In this the rufous is entirely absent, the plumage consisting wholly of brownish-black and white, the former predominating; the jugulum and the abdomen medially are conspicuously snowy-white; the black bars beneath are broad, and towards the end of each feather they become coalesced into a prevalent mottling, forming a spotted appearance.

Another (11,792, Simiahmoo, Dr. C. B. Kennerly) from Washington Territory has the black even more prevalent than in the last, being almost continuously uniform on the scapulars and lesser wing-coverts; beneath the black bars are much suffused. In this specimen the rufous tinge is present, as it is in all except the Labrador skin.

Habits. The Great Horned Owl has an extended distribution throughout at least the whole of North America from ocean to ocean, and from Central America to the Arctic regions. Throughout this widely extended area it is everywhere more or less abundant, except where it has been driven out by the increase of population. In this wide distribution the species naturally assumes varying forms and exhibits considerable diversities of coloring. These are provided with distinctive names to mark the races, but should all be regarded as belonging to one species, as they do not present any distinctive variation in habit.

Sir John Richardson speaks of it as not uncommon in the Arctic regions. It is abundant in Canada, and throughout all parts of the United States. Dr. Gambel met with it also in large numbers in the wooded regions of Upper California. Dr. Heermann found it very common around Sacramento in 1849, but afterwards, owing to the increase in population, it had become comparatively rare. Dr. Woodhouse met with it in the Indian Territory, though not abundantly. Lieutenant Couch obtained specimens in Mexico, and Mr. Schott in Texas.

Bubo virginianus.

In the regions northwest of the Yukon River, Mr. Robert Kennicott found a pair of these birds breeding on the 10th of April. The female was procured, and proved to be of a dark plumage. The nest, formed of dry spruce branches retaining their leaves, was placed near the top of a large green spruce, in thick woods. It was large, measuring three or four feet across at base. The eggs were placed in a shallow depression, which was lined with a few feathers. Two more eggs were found in the ovary of the female,—one broken, the other not larger than a musket-ball. The eggs were frozen on their way to the fort. Mr. Ross states that he found this Owl very abundant around Great Slave Lake, but that it became less common as they proceeded farther north. It was remarkably plentiful in the marshes around Fort Resolution. Its food consisted of shrews and Arvicolæ, which are very abundant there. It is very tame and easily approached, and the Chipewyan Indians are said to eat with great relish the flesh, which is generally fat.

Mr. Gunn writes that this Owl is found over all the woody regions of the Hudson Bay Territory. In the summer it visits the shores of the bay, but retires to some distance inland on the approach of winter. It hunts in the dark, preying on rabbits, mice, muskrats, partridges, and any other fowls that it can find. With its bill it breaks the bones of hares into small pieces, which its stomach is able to digest. They pair in March, the only time at which they seem to enjoy each other’s society. The nest is usually made of twigs in the fork of some large poplar, where the female lays from three to six pale-white eggs. It is easily approached in clear sunny weather, but sees very well when the sky is clouded. It is not mentioned by Mr. MacFarlane as found near Anderson River. Mr. Dall caught alive several young birds not fully fledged, June 18, on the Yukon River, below the fort. He also met with it at Nulato, where it was not common, but was more plentiful farther up the river.

Mr. Salvin found this species in August at Duenas and at San Geronimo, in Guatemala. At Duenas it was said to be resident, and is so probably throughout the whole country. It was not uncommon, and its favorite locality was one of the hillsides near that village, well covered with low trees and shrubs, and with here and there a rocky precipice. They were frequently to be met with on afternoons, and at all hours of the night they made their proximity known by their deep cry.

Dr. Kennerly found it in Texas in the cañon of Devil River, and he adds that it seemed to live indifferently among the trees and the high and precipitous cliffs. It was found throughout Texas and New Mexico, wherever there are either large trees or deep cañons that afforded a hiding-place during the day. Attracted by the camp-fires of Dr. Kennerly’s party, this Owl would occasionally sweep around their heads for a while, and then disappear in the darkness, to resume its dismal notes. Sometimes, frightened by the reverberating report of a gun, they would creep among the rocks, attempting to conceal themselves, and be thus taken alive.

Though frequently kept in captivity, the Great Horned Owl, even when taken young, is fierce and untamable, resenting all attempts at familiarity. It has no affection for its mate, this being especially true of the female. Mr. Downes mentions an instance within his knowledge, in which a female of this species, in confinement, killed and ate the male. Excepting during the brief period of mating, they are never seen in pairs.

Its flight is rapid and graceful, and more like that of an eagle than one of this family. It sails easily and in large circles. It is nocturnal in its habits, and is very rarely seen abroad in the day, and then only in cloudy weather or late in the afternoon. When detected in its hiding-place by the Jay, Crow, or King-bird, and driven forth by their annoyances, it labors under great disadvantages, and flies at random in a hesitating flight, until twilight enables it to retaliate upon its tormentors. The hooting and nocturnal cries of the Great Horned Owl are a remarkable feature in its habits. These are chiefly during its breeding-season, especially the peculiar loud and vociferous cries known as its hooting. At times it will utter a single shriek, sounding like the yell of some unearthly being, while again it barks incessantly like a dog, and the resemblance is so natural as to provoke a rejoinder from its canine prototype. Occasionally it utters sounds resembling the half-choking cries of a person nearly strangled, and, attracted by the watchfire of a camp, fly over it, shrieking a cry resembling waugh-hōō. It is not surprising that with all these combinations and variations of unearthly cries these birds should have been held in awe by the aborigines, their cries being sufficiently fearful to startle even the least timid.

It is one of the most destructive of the depredators upon the poultry-yard, far surpassing in this respect any of our Hawks. All its mischief is done at night, when it is almost impossible to detect and punish it. Whole plantations are often thus stripped in a single season.

The mating of this bird appears to have little or no reference to the season. A pair has been known to select a site for their nest, and begin to construct a new one, or seize upon that of a Red-tailed Hawk, and repair it, in September or October, keeping in its vicinity through the winter, and making their presence known by their continued hooting. Mr. Jillson found a female sitting on two eggs in February, in Hudson, Mass.; and Mr. William Street, of Easthampton, in the spring of 1869, found one of their nests on the 3d of March, the eggs in which had been incubated at least a week. If one nest is broken up, the pair immediately seek another, and make a renewed attempt to raise a brood. They rarely go more than a mile from their usual abode, and then only for food. Mr. Street’s observations have led him to conclude that they mate about February 20, and deposit their eggs from the 25th to the 28th. They cease to hoot in the vicinity of their nest from the time of their mating until their young have left them in June. On the 19th of March, 1872, Mr. Street found two of their eggs containing young nearly ready to hatch.

Mr. Street’s observations satisfied him that the period of incubation of this Owl is about three weeks. When they have young and are hard pressed for food, they hunt by day as well as by night, and at this time they hoot a good deal. The young are ready to leave their nest about six weeks after hatching. At this time their feathers are nearly all grown, except their head-feathers, which have hardly started. In the spring of 1872 Mr. Street found a young bird that had fallen from its nest. Though very small it was untamable, and not to be softened by any attentions. Its savage disposition seemed to increase with age. It readily devoured all kinds of animal food, and was especially fond of fish and snakes. It was remarkable for its cowardice, being always ridiculously fearful of the smallest dog, the near approach of one always causing extravagant manifestations of alarm. He was therefore led to conclude that it does not prey upon quadrupeds larger than a hare, that it rarely is able to seize small birds, and that reptiles and fish form no inconsiderable portion of its food. The young Owl in question assumed its full plumage in November, when less than eight months old. It was of full size in all respects except in the length of its claws, which were hardly half the usual size.

Mr. T. H. Jackson, of West Chester, Penn., has met with fresh eggs of this Owl, February 13, 22, and 28, and has found young birds in their nests from the 2d of March to the 28th.

Mr. Audubon states that while the Great Horned Owl usually nests in large hollows of decayed trees, he has twice found the eggs in the fissures of rocks. In all these cases, little preparation had been made previous to the laying of the eggs, the bed consisting of only a few grasses and feathers. Wilson, who found them breeding in the swamps of New Jersey, states that the nest was generally constructed in the fork of a tall tree, but sometimes in a smaller tree. They begin to build towards the close of winter, and, even in the Arctic regions, Sir John Richardson speaks of their hatching their eggs as early as March. The shape of the egg is very nearly exactly spherical, and its color is a dull white with a slightly yellowish tinge. An egg formerly in the old Peale’s Museum of Philadelphia, taken in New Jersey by Alexander Wilson the ornithologist, and bearing his autograph upon its shell, measures 2.31 inches in length by 2.00 in breadth. Another, obtained in the vicinity of Salem, Mass., measures 2.25 inches in length by 1.88 in breadth. In the latter instance the nest was constructed on a tall and inaccessible tree in a somewhat exposed locality. The female was shot on the nest, and, as she fell, she clutched one of the eggs in a convulsive grasp, and brought it in her claws to the ground. An egg obtained in Tamaulipas, Mexico, on the Rio Grande, by Dr. Berlandier, measures 2.18 inches in length by 1.81 in breadth.

An egg from Wisconsin, taken by Mr. B. F. Goss, may be considered as about the average in size and color. It is nearly spherical, of a clear bluish-white, and measures 2.30 by 2.00 inches.

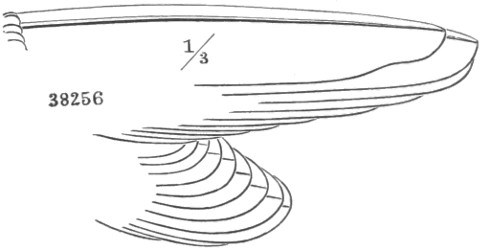

38256 ⅓

Otus wilsonianus.

Nyctea scandiaca, var. arctica, GrayAMERICAN SNOWY OWL

Strix arctica, Bartram, Trav. in Carolina, 1792, p. 285. Strix nyctea, (not of Linn.!) Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. 1807, pl. xviii.—Swains. & Rich. F. B. A. II, 1831, 88.—Bonap. Ann. N. Y. Lyc. II, 36.—Wils. Am. Orn. pl. xxxii, f. 1.—Aud. Birds Am. pl. cxxi.—Ib. Orn. Biog. II, 135.—Thomps. Nat. Hist. Vermont, p. 64.—Peab. Birds Mass. III, 84. Surnia nyctea (Edmondst.), James. (ed. Wils.), Am. Orn. I, 1831, 92.—Nutt. Man. p. 116.—Kaup, Tr. Zoöl. Soc. IV, 1859, 214. Syrnia nyctea (Thomps.), Jardine’s (ed. Wils.) Am. Orn. II, 1832, 46. Nyctea nivea, (Gray) Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. 1854, 100.—Ib. Birds N. Am. 1858, 63.—Newton, P. Z. S. 1861, 394 (eggs).—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 330 (Texas!).—Dall & Bannister, Tr. Chicago Acad. I, ii, 1869, 273 (Alaska).—Coues, Key, 1872, 205. Nyctea candida, (Lath.) Bonap. List, 1838, 6.

Sp. Char. Adult. Ground-color entirely snow-white, this marked with transverse bars of clear dusky, of varying amount in different individuals.

♂ (No. 12,059, Washington, D. C., December 4, 1858; C. Drexler). Across the top of the head, and interspersed over the wings and scapulars, are small transversely cordate spots of clear brownish-black, these inclining to the form of regular transverse bars on the scapulars; there is but one on each feather. The secondaries have mottled bars of more dilute dusky; the primaries have spots of black at their ends; the tail has a single series of irregular dusky spots crossing it near the end. Abdomen, sides, and flanks with transverse crescentic bars of clear brownish-black. Wing, 16.50; tail, 9.00; culmen, 1.00; tarsus, 1.90; middle toe, 1.30. Wing-formula, 3, 2=4–5, 1.

♀ (No. 12,058, Washington, D. C., December 4, 1858). Head above and nape with each feather blackish centrally, producing a conspicuously spotted appearance. Rest of the plumage with regular, sharply defined transverse bars of clear brownish-black; those of the upper surface more crescentic, those on the lower tail-coverts narrower and more distant. Tail crossed by five bands, composed of detached transverse spots. Only the face, foreneck, middle of the breast, and feet, are immaculate; everywhere else, excepting on the crissum, the dusky and white are in nearly equal amount. Wing, 18.00; tail, 9.80; culmen, 1.10. Wing-formula, 3=4, 2–1=5.

Young (No. 36,434, Arctic America, August, 1863; MacFarlane). Only partially feathered. Wings and tail as in the adult female described, but the blackish bars rather broader. Down covering the head and body dark brownish or sooty slate, becoming paler on the legs.

Hab. Northern portions of the Nearctic Realm. Breeding in the arctic and subarctic regions, and migrating in winter to the verge of the tropics. Bermuda (Jardine); South Carolina (Bartram and Audubon); Texas (Dresser).

Localities: Texas, San Antonio (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 330).

The Snowy Owls of North America, though varying greatly among themselves, seem to be considerably darker, both in the extremes and average conditions of plumage, than European examples. Not only are the dusky bars darker, but they are usually broader, and more extended over the general surface.

Habits. This is an exclusively northern species, and is chiefly confined to the Arctic Circle and the adjacent portions of the temperate zone. It is met with in the United States only in midwinter, and is much more abundant in some years than in others. Individual specimens have been occasionally noticed as far south as South Carolina, but very rarely. It has also been observed in Kentucky, Ohio, the Bermuda Islands, and in nearly every part of the United States.

Nyctea scandiaca.

In the Arctic regions of North America and in Greenland it is quite abundant, and has been observed as far to the north as Arctic voyagers have yet reached. Professor Reinhardt states that it is much more numerous in the northern than in the southern part of Greenland. Sir John Richardson, who, during seven years’ residence in the Arctic regions, enjoyed unusual opportunities for studying the habits of this Owl, says that it hunts its prey in the daytime. It is generally found on the Barren Grounds, but is always so wary as to be approached with difficulty. In the wooded districts it is less cautious.

Mr. Downes states that this Owl is very abundant in Nova Scotia in winter, and that it is known to breed in the neighboring province of Newfoundland. In some years it appears to traverse the country in large flocks. In the winter of 1861–62, he adds, these birds made their appearance in Canada in large numbers.

Mr. Boardman states that they are present in winter in the vicinity of Calais, but that they are not common. A pair was noticed in the spring of 1862 as late as the last of May, and, in Mr. Boardman’s opinion, were breeding in that neighborhood. In the western part of Maine Mr. Verrill found it also rather rare, and met with it only in winter. He states that it differs greatly in disposition from the Great Horned Owl, being naturally very gentle, and becoming very readily quite tame in confinement, differing very much in this respect from most large Raptores.

It makes its appearance in Massachusetts about the middle or last of November, and in some seasons is quite common, though never present in very large numbers. It is bold, but rather wary; coming into thick groves of trees in close proximity to cities, which indeed it frequently enters, but keeping a sharp lookout, and never suffering a near approach. It hunts by daylight, and appears to distinguish objects without difficulty. Its flight is noiseless, graceful, easy, and at times quite rapid. In some seasons it appears to wander over the whole of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains, Dr. Heermann having obtained a specimen of it near San Antonio, Texas, in the winter of 1857.

It is more abundant, in winter, near the coast, than in the interior, and in the latter keeps in the neighborhood of rivers and streams, watching by the open places for opportunities to catch fish. Mr. Audubon describes it as very expert and cunning in fishing, crouching on the edges of air-holes in the ice, and instantly seizing any fish that may come to the surface. It also feeds on hares, squirrels, rats, and other small animals. It watches the traps set for animals, especially muskrats, and devours them when caught. In the stomach of one Mr. Audubon found the whole of a large house-rat. Its own flesh, Mr. Audubon affirms, is fine and delicate, and furnishes very good eating. It is described as a very silent bird, and Mr. Audubon has never known it to utter a note or to make any sound.

Richardson states that a few remain in the Arctic regions even in midwinter, but usually in the more sheltered districts, whither it has followed the Ptarmigan, on which it feeds. When seen on the Barren Grounds, it was generally squatting on the earth, and, if disturbed, alighted again after a short flight. In the more wooded districts it is said to be bolder, and is even known to watch the Grouse-shooters, and to share in their spoils, skimming from its perch on a high tree, and carrying off the bird before the sportsman can get near it.