полная версия

полная версияThe Day After Death (New Edition). Our Future Life According to Science

Thus heat and life would be the manifestation of one and the same power, and the cause of life would be found to dwell, like the cause of mechanical force, in the sun.

CHAPTER THE EIGHTH

THE SUN THE DEFINITIVE ABODE OF SOULS WHO HAVE ATTAINED THE HIGHEST RANK IN THE CELESTIAL HIERARCHY.—THE SUN THE FINAL AND COMMON DWELLING OF SOULS WHO HAVE COME FROM THE EARTH.—THE PHYSICAL CONSTITUTION OF THE SUN.—THE SUN IS A MASS OF BURNING GASESTHE fundamental importance of the sun in the general economy of our world being finally established, our readers will not be surprised to hear that we assign that radiant and sublime abode to the human souls released from the earth, and successively purified and perfected by the long series of their multiplied incarnations in the bosom of the interplanetary spaces. Some philosophers have perceived this truth. The astronomer Bode placed the most elevated intelligences in the sun. "The happy creatures which inhabit this privileged abode," he says, "have no need of the alternate succession of day and night; a pure and unextinguishable light illumines it for ever. In the centre of the light of the sun, they enjoy perfect security, under the shelter of the wings of the Almighty."6 Under what form may we picture to our fancy the inhabitants of the sun? We cannot answer this question without being acquainted with the geography of the sun, or as astronomers call it, his physical constitution, which differs essentially from that of the planets, of their satellites, and of the comets. He is unique in his position and office in the planetary system,—he must therefore be specially constituted. What is this special constitution? What is the geography of the sun?

Would that it were in our power to reply to this question with precision; would that we could describe the configuration of the sun. Unhappily, science has not yet reached that point. The problem of the sun's true nature is full of uncertainty. Astronomers are divided between two opposite theories, and that which seems to be the best supported, is too recent to be set forth in a dogmatic fashion. We can only summarize the actual condition of our knowledge on this question, explain the theory which seems conformable to ascertained facts, and applying it to the subject on which we are engaged, endeavour to deduce the physical condition, which, in our opinion, would belong to the inhabitants of the king-star.

Until the great epoch of the discovery of the telescope, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, in the time of Keppler and Galileo, only vague and arbitrary ideas respecting the sun prevailed. The educated, as well as the vulgar, beheld in it merely a globe of fire; the most learned declared that they found in it pure fire, elementary fire, the principle of light, and of fire. But as no means existed of examining the surface of the sun, and as his real distance from the earth was either unknown, or very imperfectly understood, a prudent reserve was maintained on this question. The discovery of the telescope immediately placed the astronomers in possession of the celestial realm; it enabled them to sound the depths of space, and to study the apparent configuration of the stars, including the sun himself. A few hours' observation with the astronomical spy-glass, and more was learned of the nature of the sun, than in the two thousand years of more or less philosophical reverie which preceded the discovery of the telescope.

With a glass which magnified the apparent diameter of the sun only twenty-sixfold, Galileo, repeating the observations of Fabricius, discovered the spots on the sun. Although Galileo did not use the smoked glasses which have since been found so useful, and although he limited his observations to the horizon, watching the great star at its rising and its setting, or when it was veiled by slight clouds, he studied its spots carefully, and described them faithfully.

We may observe that this discovery astonished the philosophers of that period, who were entirely submissive to the authority of Aristotle. The incorruptibility of the sun was held in the schools as a sacred principle, according to Aristotle, and these unfortunate spots perplexed the philosophers. The peripatetics vied with each other in proving to the Florentine astronomer that the purity of the sun was an unassailable principle, and that the spots which he had perceived existed only on his eyes, or on the lens of his glasses.

But Galileo had seen correctly, and soon every one could convince himself of the reality of the phenomenon he had proclaimed. Not only do spots exist upon the disc of the sun, but they furnish the only means which we possess of becoming acquainted with the physical and astronomical peculiarities and properties of the great star. The examination of these spots led to the discovery that the sun revolves like the other planets, and that he accomplishes the entire revolution upon his axis in a period of twenty-five days. The sun's days are therefore twenty-five times as long as ours. Here, however, we must remark upon the word day. To us, the day signifies the periodical return of the earth to the same point, after a complete revolution upon its axis, with an alternation of light and darkness. It is quite otherwise in the case of the sun, which, being self-luminous in all his parts, can never have any night.

We have said that the examination of the sun's spots established his rotation upon his axis. In fact, if we patiently observe the motion of a spot, or of a group of spots, we remark that it advances slowly from one edge of the solar disc to the other; for instance, if the point of departure be the eastern edge, the spot or group will advance with uniform speed towards the western edge, taking fourteen days to accomplish the distance. If we wait fourteen days more, we shall again perceive the same spot making its appearance on the eastern edge of the disc, the interval having been consumed in passing over the opposite and, of course, invisible side of the sun. The spot has therefore taken twenty-eight days to reappear, which twenty-eight days do not, however, represent the exact duration of the revolution of the sun himself. It must not be forgotten that the earth has not remained motionless during this long observation; she, too, has gone round in the sun, as the spots have done. This sort of advance, which causes us to see the same spot for a longer time than we should have seen it, if the earth remained motionless, is of three days' extent, the deduction of which from the twenty-eight given days, allows twenty-five days for the real duration of the sun's rotation upon his axis.

In the sun seasons are unknown as well as days. Time seems to have no existence for the beings who occupy that radiant dwelling-place. The changes, and the succession of things for us which constitute time, are unknown to their sublime essence. Duration has no measure in that blessed world.

The dweller in the sun must behold the revolution of the planets around him, performed according to the same laws, but with different rates of speed. The phases of the planets and their satellites, the phases of Mars and Venus, or those of the moon, which we perceive from the earth, are unknown to them; they see only the hemisphere of those globes which is illumined by their own immense country. They behold, in larger dimensions, the globes of Mercury and Venus, and in lesser dimensions the Earth and Mars. The distant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus, must seem very small to them. Neptune they probably cannot see at all. The comets must be for a long time invisible to the inhabitants of the sun, who behold their flaming mass rushing towards them in ever-increasing size. They also see some comets sinking away into space, and others falling on the surface of the sun himself, to be lost and absorbed in his substance.

Thus, the spots on the sun have revealed to us an important peculiarity of his astronomical character, his revolution upon his axis. They have also given us the only exact ideas which we possess of the physical constitution of the sun.

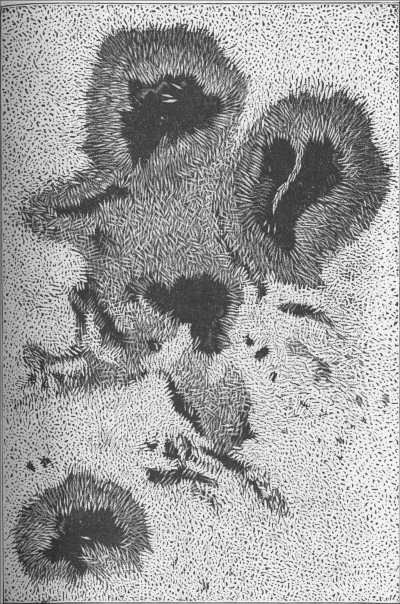

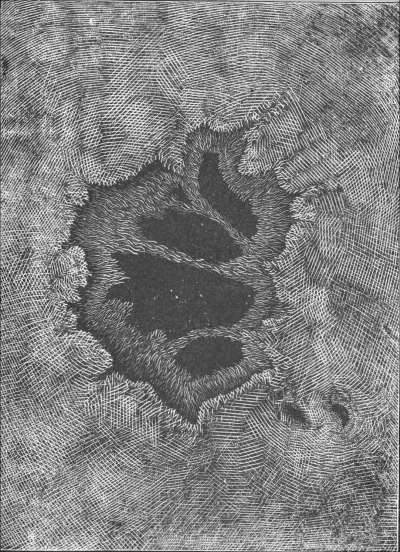

The accompanying plate conveys an idea of what the spots on the sun consist of. Figures 2 and 3 represent the general aspect of these appearances. In the centre is a black space perfectly marked. To this succeeds a space in grey tinting, whose outlines melt by degrees into the rest of the luminous mass. The first region is called the Umbra; the second, the Penumbra.

These words must be distinctly understood. The part indicated by the term Umbra is only dark relatively to the illumined portion. This Umbra is very luminous, its brilliancy is two thousand times that of the full moon. We are merely dealing with comparisons here. The solar spots are often of very considerable dimensions. They have been found 30,000 leagues in breadth, and could swallow up the earth, which is only one-tenth of that magnitude. They are not permanent, sometimes they remain for months, or even years, but the greater number increase and decrease rapidly, and disappear in a few weeks. They are incessantly changing in form and in extent, and they grow and diminish. It is evident that they are regulated by a violent interior movement, and that they are the seat of tumultuous motion. Something like whirlwinds are seen to sweep across the regions occupied by the spots, and to carry them away, like the waves of a furious sea, or the flames of a conflagration. Gigantic bridges of apparently burning matter have been observed, thrown from one edge to the other of adjacent spots, uniting them by a shining band, and then this same band has stretched itself out and caught hold of other spots. Of a sudden the whole edifice has been seen to be swept away by fresh whirlwinds. Signs of a prodigious commotion, of gigantic perturbation, are always evident. These hurricanes, these tempests of flame, are of a widely different grandeur from the hurricanes and the tempests of our atmosphere, because the atmosphere of the sun is several thousands of yards in height, and covers an extent of surface 1,300,000 times greater than ours.

Fig. 2.—Group of Solar Spots observed in 1864 by Nasmith.

Fig. 3.—Another Solar Spot observed by Nasmyth.

We have just said that the sun has an atmosphere. Such is the conclusion to which the careful examination of the great star has led.

From the earliest times at which the sun was observed, a theory of its constitution was formulated, which was perpetuated down to the present age, without receiving authoritative contradiction. In the eighteenth century the astronomers Herschel and Wilson developed this theory, which was popularized in our time by the writings of Humboldt and Arago.

According to this theory, the sun is composed of a dark nucleus, and a burning atmosphere, which is the only source of the light proper to this star. Arago and Humboldt called the incandescent atmosphere of the sun, the photosphere. Heat and light would not, therefore, come to us from the nucleus, but only from the photosphere.

The spots are explained, according to this theory, by admitting that they are openings accidentally formed in the sun's atmosphere by gases discharged from volcanic craters, or in some other way. Through these openings the dark nucleus of the sun is seen. The penumbra of the spots are formed by the lower parts of the atmosphere of the sun, which is either hot or luminous. This lower portion of the atmosphere, reflecting the light emitted by the upper portion or photosphere, is slightly warm, and only partially illumined.

This theory of the constitution of the sun, and of the solar spots, seemed for a long time satisfactory. A similar explanation, that is to say, by partial eruptions of gas from volcanic craters, was assigned to the kind of black dotted appearance observed on the surface of the solar disc, and which is exactly reproduced in the two figures here given.

The brilliant spots scattered over the surface of the sun, which touched here and there with points of intense luminosity, are called faculæ. These brilliant points are said to proceed from local accidents, which cause an escape of light and heat from certain parts of the solar atmosphere.

Thus, according to this theory, the sun would be a solid body, opaque and dark like the planets, surrounded by an atmospheric layer, which would prevent any heat in the nucleus. Outside that layer would be a second atmosphere, the photosphere, which only would be luminous, and capable of emitting light and heat. Dark nucleus, dark atmosphere, luminous photosphere, such would be the constituent elements of the sun, according to Wilson, William Herschel, Humboldt, and Arago. To any who hold this theory, it is not impossible to believe that the sun may be inhabited by beings who differ but slightly to man, or who are endowed with an organization similar to that of the inhabitants of the earth. If the body of the sun be preserved by the interposition of a cold, and but slightly conducting atmosphere from the rays of the photosphere which burns at an immense distance, we can believe that creatures organized almost like ourselves could live within it. The heat of the burning photosphere can reach it through the thickness of the lower atmosphere with only the degree of heat necessary to maintain life. The light thus filtered is brilliant, but not dazzling, and admits of the existence of beings of organization similar to those who live on the earth.

To this conclusion Arago came:

"If I were asked," said the astronomer, "is the sun inhabited? I must reply that I do not know. But, if I were asked whether the sun can be inhabited by beings of organization similar to that of dwellers upon our globe, I should not hesitate to reply in the affirmative."

At the present day Arago would hesitate, for science has made a great advance in the question of the physical constitution of the sun. The new method invented by MM. Kirchhoff and Bunsen, and known as analysis of the luminous spectrum, being applied to the solar rays, has given rise to an entirely new conception of the nature of the sun. We have returned to the opinion of the physicists of the middle ages, who regarded the sun as a globe of fire, a sort of gigantic torch.

It would be impossible to enter into the details of the optical experiments which rendered accurate analysis of the solar rays possible, and enabled us to deduce a new theory of the constitution of the sun from their properties. We shall confine ourselves to explaining this theory, as it evolves itself from the experiments of M. Kirchhoff.

According to the German philosopher, the sun is not, as it has hitherto been supposed, a cold, dark, and solid body, surrounded by a burning atmosphere; it is a globe, a sphere, probably liquid, which burns throughout its whole mass, and in all its parts. This incandescent globe is surrounded by a very heavy atmosphere, formed of the vapours which proceed from the incandescent globe, and which are themselves kept burning in consequence of the high temperature of all those masses of fire.

How are the spots on the sun to be explained according to this theory? M. Kirchhoff admits that, owing to unknown causes, a cooling process may take place in the vaporous atmosphere which surrounds the body of the sun. This cooling process would form at certain points condensations of vapour analogous to the condensation of the vapour of water, which on our globe produces clouds and rain. These agglomerations of condensed vapours would form a species of cloud in the atmosphere of the sun, and those clouds, which would intercept the light of the solar disc from us, would produce the effect of a spot on this disc. The cloud, once formed, cools portions of the neighbouring vapours, and, by provoking a partial condensation, gives rise to the penumbra which surround the umbra. Thus, according to M. Kirchhoff, the solar spots are clouds suspended in the sun's atmosphere. Galileo had previously propounded an analogous hypothesis. Without abandoning M. Kirchhoff's theory we may mention another explanation of the spots. A German physicist considers the spots, not as clouds in the sun's atmosphere, but as partial solidifications of the liquid matter which forms the body of the sun; a kind of scoria, analogous to those which may be observed in crucibles containing matters in a state of fusion, and which come from particles of metal not yet melted, or which are beginning to solidify. The penumbra of the spots would be the half-molten, and consequently, half-transparent pollicule which always surrounds the edges of metallic scoria with a semi-liquid ring.

M. Faye, a French astronomer, has propounded a theory, which somewhat modifies that of M. Kirchhoff. He thinks that the nucleus of the sun is neither solid nor liquid, but entirely gaseous. The solar spot, he, like M. Kirchhoff, takes to be an opening made accidentally in the sun's atmosphere by the condensation of vapours on certain points of that atmosphere. According to M. Faye, the spots are due to vertical currents of vapour ascending and descending, and the interception of the light of the sun's atmosphere by the predominant intensity of the ascending current.7

The new theory, the result of the optical experiments of the German physicists, appears to explain all the facts which have been observed, and it has therefore been generally accepted. Some divergences exist on questions of detail, but astronomers are nowadays almost unanimous in regarding the sun as a great body, incandescent in all its parts, as a globe in a state of fusion, surrounded by a burning atmosphere, or, as M. Faye states it, a simple agglomeration of incandescent gases.

CHAPTER THE NINTH

THE INHABITANTS OF THE SUN ARE PURELY SPIRITUAL BEINGS.—THE SOLAR RAYS ARE EMANATIONS FROM THE SPIRITUAL BEINGS WHO LIVE IN THE SUN.—THESE BEINGS THUS PRODUCE ANIMAL AND VEGETABLE LIFE UPON THE EARTH.—THE CONTINUITY OF SOLAR RADIATION, INEXPLICABLE BY PHYSICISTS, EXPLAINED BY THE EMANATION FROM THE SOULS OF THE INHABITANTS OF THE SUN.—THE WORSHIP OF FIRE, AND THE ADORATION OF THE SUN AMONG DIFFERENT PEOPLES, ANCIENT AND MODERNFROM the discussion of physical astronomy contained in the preceding chapters, we have concluded, with MM. Kirchhoff and Faye, that the sun is a mass of burning gases. But, our readers will ask, if this be so—if the sun is a gaseous incandescent mass, or a globe of matter in a state of fusion, surrounded by an atmosphere of burning gas, where do you place its inhabitants, and under what form do you picture them?

We have already said, that at each step of their promotion in the hierarchy, the creatures who live in the planetary spaces and have succeeded to the superhuman being, grow in perfection, their senses are multiplied, their intellectual power is considerably extended. In proportion as the creature, who in the beginning was human, is raised by successive deaths and resurrections in the scale of inter-planetary being, the material substance, which, united to its spiritual principle, formed its radiant individuality, is diminished. In further exposition of our system, we must state our belief that this superior being, when he has been sufficiently perfected and exalted, by his different incarnations, by the multiplied stages in the immensity of the heavens, finally becomes pure spirit. When he attains the sun, he is free from all material substance, from all carnal alloy. He is a flame, a breath; all is intelligence, sentiment, thought, in him; nothing impure is mingled with his perfect essence. He is an absolute soul, a soul without a body. The gaseous and burning mass of which the sun is composed is, therefore, appropriate to receive these quintessential beings. A throne of fire is a fitting throne for souls.

We might even go further, and maintain that not only is the sun the asylum and receptacle of souls which have finished the course of their peregrinations in this world, but that it is nothing else than a collection of those souls which have come to it from the other planets, after having passed through the intermediate states which we have described. The sun may be only an aggregation of souls.

Since the sun is the first cause of life on our globe, since he is, as we have proved, the origin of life, feeling, and thought, since he is the determining cause of the existence of everything possessing organization upon the earth, why may we not hold that the rays which the sun pours upon the earth and the other planets are nothing else than the emanations from these souls? that they are emissions from the pure spirits dwelling in the central star, directed towards us, and the other planets, under the visible form of rays?

If this hypothesis were accepted, what magnificent, what sublime relations existing between the sun and the globes which gravitate around him, would be revealed to us! A continual exchange would be established between the sun and the surrounding planets, an unbroken circle, an inexhaustible communion, radiant emanations which should generate and maintain activity and motion, thought and sentiment, which should keep the flame of life burning everywhere! Let us think of the emanations from souls dwelling in the sun descending upon the earth in solar rays. Light gives existence to plants, and produces vegetable life, accompanied by sensibility. Plants, having received this sensible germ from the sun, communicate it, aided by heat likewise emanating from the sun, to animals. Let us think of the germs of souls, placed in the breasts of animals, developing themselves, becoming perfected by degrees, from one animal to another, and finishing by becoming incarnate in a human body. Let us think, then, of the superhuman being succeeding to man, springing up into the vast plains of ether, and beginning the series of numerous transmigrations which, from one step to another, will lead him to the summit of the scale of spiritual perfection, from which every material substance has been eliminated, and where the soul, thus exalted to the purest degree of its essence, penetrates into the supreme abode of happiness, and of intellectual and moral power—the sun.

Such may be this endless circle, such this unbroken chain, binding together all beings in nature, and passing from the visible to the invisible world.

To those persons who may declaim with severity against the system which we have ventured to put forward, we shall put a question which cannot fail to embarrass them, for science has never been able to solve it. We shall ask them how the light of the sun, and the heat which results from it, are maintained? It is evident that the enormous quantities of heat and light which the sun sends out in torrents into space, must come from a source which cannot be inexhaustible, which has need of renewal, otherwise the sun would become extinct. As there is no effect without a cause, it is plain that the inconceivable quantity of forces which the sun distributes by his burning rays, must be derived from some place. M. Guillemin, in his work on the sun, passes in review the different theories which have been adopted, up to the present day, to explain solar radiation. The following is an analysis of a chapter of M. Guillemin's work on the "Maintenance of Solar Radiation."

Pouillet has calculated that if the sun were not supplied with something to make up for the losses he sustains, he must cool at the rate of one degree in a century. But this calculation falls short of the truth. Pouillet supposed that the specific heat of the sun is the greatest which can be conceived. The specific heat of the sun is, it is true, unknown, but instead of placing it at the maximum power, which it is not proved to be, we might suppose it, by an allowable hypothesis, to be equal to that of water, which is well known. Now if we grant to the sun the specific heat of water, we rectify Pouillet's calculation, and we arrive at the conclusion that the sun, if not furnished with any resources from which to repair his losses, would be entirely extinct at the end of 10,000 years. Professor Tyndall, whose experiments are more recent than those of Pouillet, and inspire greater confidence, says: "If the sun were a block of coal, and it were supplied with sufficient oxygen to enable it to burn at the degree of heat proper to that star, it would be entirely consumed at the end of 5000 years." Now the sun has existed for millions of years, for the transition periods of our globe, in which the first living beings were manifested, are traced back to millions of years. And yet his heat has not sensibly diminished since those distant ages. The proof that it has not diminished, is that the climates of the globe at the present time are the same as they were in the tertiary or quaternary epoch. In the tertiary or quaternary strata the same plants and the same animals which exist at present are found. Speaking of times nearer to our own, we may observe that the productions of the soil remain unchanged during the 2000 or 3000 years, whose traditions and historical archives we possess.