полная версия

полная версияThe Day After Death (New Edition). Our Future Life According to Science

Asteroids. Jupiter. Saturn. Uranus. Neptune.

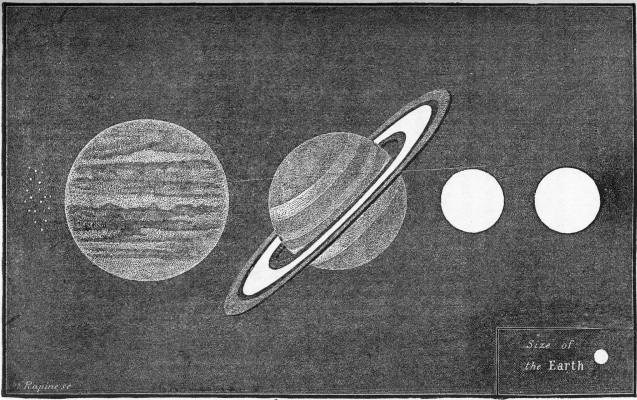

Fig. 5.—Size of the Planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune compared with the Earth.

This rapid glance at our solar system in its entirety, proves that the earth is not in possession of any privilege. The part which she plays in the economy of the universe is equally fulfilled by other stars, and there is nothing to justify the pre-eminence assigned to her by the ancients. She is not the largest, the warmest, or the brightest of the planets. She simply forms a portion of a group of stars, and is but one individual of that group.

These considerations tend to lead us to a very important deduction. Since the earth is in no way distinguished from the other planets of our solar system, there must exist in other planets the things which are found on our globe; air, water, a hard soil, rivers and seas, mountains and valleys. Even vegetation and forests ought to be there, regions covered with verdure and with shade. So there surely ought to exist in the other planets, animals, and even men, or at least creatures superior to animals, corresponding to our human type.

But is this possible? is it true? are the planets which, like the earth, and together with it, turn round the sun, constituted physically as the earth is? Are they covered with vegetable growth? are they tenanted by animals and by beings belonging to the human type?

This grave question has been profoundly discussed by M. Camille Flammarion, in a work entitled Pluralité des Mondes Habités, and in a later publication, Les Mondes Imaginaires et les Mondes Réels. It would be outside the province of this book to follow the author through the various scientific considerations, from which he reasons that the planets which form a portion of our solar system, are, like the earth, the scene of life, organization, thought, and feeling. In the 17th century, Fontenelle and Huygens had successfully approached this successful problem, which M. Camille Flammarion has lately treated with especial care and development, invoking the lessons of contemporaneous astronomy and physics, which refer to the subject. We therefore refer the reader, who wishes to be instructed upon the question of the possibility of the planets being inhabited, to M. Flammarion's works.

CHAPTER THE FOURTEENTH

THAT WHICH HAS TAKEN PLACE UPON THE EARTH WITH REGARD TO THE CREATION OF ORGANIZED BEINGS HAS PROBABLY ALSO TAKEN PLACE IN THE OTHER PLANETS.—THE SUCCESSIVE ORDER OF THE APPEARANCE OF LIVING BEINGS ON OUR GLOBE.—THIS SAME SUCCESSION HAS PROBABLY TAKEN PLACE IN EACH OF THE PLANETS.—PLANETARY MAN.—THE PLANETARY, LIKE THE TERRESTRIAL MAN, IS TRANSFORMED, AFTER DEATH, INTO A SUPERHUMAN BEING, AND PASSES INTO THE ETHERWE believe, with M. Camille Flammarion, that organized beings exist in all the planets. But are these beings who live in the distant worlds accompanied, like terrestrial man, by a superior type? This is the subject which we now propose to examine. In the absence of observation analogy is our only means of investigation, and, guided by analogy, we must admit that the processes which have taken place upon the earth, since the epoch of its formation, must have similarly taken place upon all the other planets, the earth's congeners.

We are now perfectly acquainted with the manner in which the vegetable and animal creations have appeared, and succeeded each other upon our globe since its origin. At first the earth was simply a collection of gas, and burning vapour which revolved round the sun. This mass of gas and vapour grew cold by degrees in its passage through space, and first becoming liquid, afterwards assumed the consistency of paste, and ultimately became solid, by a gradual process of refrigeration. Consolidation began on the surface, because the circumference of a sphere is more exposed than the remainder of the mass to refrigerating influences. Then the water and the vapours which still flowed upon the consolidated globe became condensed, and, falling in burning showers upon the hard soil, they formed the first seas.

The proof that the earth's primitive condition was like to a liquid or half paste, is, that if we take a plastic sphere, for instance a slightly fluid ball of quicksilver, and make it turn rapidly upon its axis, we observe that it swells out in the middle, and becomes flat at the two poles, or the extremities of the axis; this is the effect of the centrifugal force engendered by the rotatory motion. Now the earth is depressed at the poles, and slightly swelled out at the equator.

The other planets must have been formed by the same process as the earth. They were, no doubt, composed of a collection of gas and vapours, which became liquid, pasty, and eventually solid, by a process of refrigeration. This process, taking effect especially upon their surface, they began to put forth a skin, or exterior and solid covering, which was the soil of the planet. On this resisting soil fell the liquids resulting from the condensation of the water vapour, and thus the first seas of the planets were formed.

We would remind those who doubt the correctness of this theory that the poles of the globe of Saturn and that of Jupiter are much more flat than those of the Earth; which is explained by the greater velocity of the rotation of each upon its axis. Our days are 24 hours long, whereas those of Jupiter and Saturn are only 10 hours. Greater rapidity of rotation produces a correspondingly increased depression at the extremities of the axis. This geometrical result demonstrates the justice of the assimilation in their respective origin which we maintain between the Earth and the other planets.

In the warm waters of the basin of the seas the first living beings which existed upon our globe appeared. Animal life commenced in the waters, in the primitive forms of zoophytes and mollusca, as we know, because zoophytes and mollusca, with the addition of a few articulates, composed the animal remains found in the transition strata which come after the primary formations. The first vegetables are found in the same transition strata, they are mosses, algæ, and ferns.

When the earth had become somewhat cooler, phanerogamous vegetables appeared upon the continents. Numerous vegetable species were simultaneously created, for the flora of the secondary formations is extremely rich and varied.

It was the same in the case of animals. So the zoophytes, mollusca, and fish which existed in the transition period succeeded reptiles, in the secondary formation, which inhabited both land and sea. At this period appeared those monstrous saurian reptiles, whose formidable shapes, and colossal dimensions fill us with surprise and almost with dismay. Then the gigantic mosasaurus ravaged the seas, the terrible ichthyosaurus spread terror among the inhabitants of the waters, and the gigantic iguanodon laid waste the forests. The secondary formation, which is filled with their remains, shows us that at that period reptiles held the first rank in creation.

At a later date, the atmosphere having become purer, birds began to traverse the air. In the tertiary deposit we find the remains of several kinds of birds, and these remains, which do not exist in the earlier formations, sufficiently prove that it was in the tertiary period that birds made their first appearance upon the terrestrial globe.

Still later, at a more advanced period of the tertiary epoch, mammifers appear upon the scene. We must observe that these animal species do not replace each other, that the one does not exclude the other. Several of the ancient animal species continue to exist after the appearance of entirely novel kinds. We might quote as instances whole groups of animals, such as the lingulæ (mollusca), the coral (zoophyte) among animals, and among vegetables, the algæ, ferns, and lycopodes, which appeared on our globe in the earliest period of the reign of organization, and have never ceased to exist. It was not until the last epoch in the history of the Earth, during the quaternary epoch, that man appeared, the highest product of living creation, the ultimate term of organic, intellectual, and moral progress, the crowning upon our earth of the visible edifice of nature.

At present, man lives together with the animals which began to exist during the quaternary epoch, and a great number of other kinds of mammifers which were created during the tertiary epoch.

The various phases of the development of the animal and vegetable kingdoms on our globe, these perfected organized species each succeeding the other, and finally reaching the superior type which we call man, must, in our opinion, have been produced in the selfsame order, upon the other planets of our solar world. M. Flammarion proves, in the work which we have already quoted, that the physical and climatological constitution of the planets is similar to that of our globe. There is therefore no reason why things should have taken place otherwise in Mercury, Jupiter, or Venus, than in the Earth, in respect to the successive order of the creation and appearance of living beings, and, in our belief a precisely similar successive appearance of vegetables and animals, has taken place in these planets. The plants and animals of Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, &c., were certainly not identical with those species which have had existence on the Earth, and perhaps no resemblance could be traced between them, but all, in their successive appearance, obeyed the principle of progress and perfecting. Life, commencing in the burning waves of the primitive seas, subsequently manifested itself upon the continents. Animals of aërial organization have lived upon these continents, their species have by degrees reached the perfection of their type, at length, and finally, a creature appeared in these planets more complete, superior in organization, intelligence, and sensibility to all the animal creation which formed the population of each particular globe.

This superior being, this last step of the ascending scale of living creation proper to the planetary worlds, the corresponding analogous creature to terrestrial man, we shall take leave to call planetary man.

In all the planets, then, there exist men, as on the earth, just as there exist animals which are inferior to that noble and privileged type.

According to the views which we have explained at the commencement of this work, terrestrial man undergoes, after his death, a glorious metamorphosis. Leaving his miserable material covering here below, his soul springs upward into space, and becomes incarnate in a new being, whose type is infinitely superior, by reason of its moral perfection, to that of our poor humanity. He becomes that which we have called the superhuman being. If this be true of the terrestrial man, it must be equally true of the planetary man. So that the superhuman being must proceed, not only from the earth, but from all the other planets.

Superhuman beings come from the human souls who have lived either upon the Earth, or upon Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, &c. And precisely as the superhuman being, who comes from the Earth passes into the surrounding ether, so the planetary man, leaving Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, &c., passes into the ether, which surrounds his own planet, becomes incarnate in a superhuman being, and lives in the ethereal plains adjoining the planet which he has quitted.

All these superhuman beings float in the clouds of ether which, in the case of every planet, succeed to its atmosphere.

Thus, the principles upon which we have based terrestrial humanity, are general, and apply to all planetary humanity. Not from the Earth only do those souls proceed who are incarnate in new creatures in the bosom of the ethereal spaces, these souls proceed from all the globes which, together with the Earth, form the attendant court of the royal Sun.

CHAPTER THE FIFTEENTH

PROOFS OF THE PLURALITY OF HUMAN EXISTENCES, AND OF RE-INCARNATIONS.—APART FROM THIS DOCTRINE IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO EXPLAIN THE PRESENCE OF MAN UPON THE EARTH, THE SAD AND UNEQUAL CONDITIONS OF HUMAN LIFE, AND THE FATE OF CHILDREN WHO DIE IN INFANCYTHE doctrine of the plurality of existences, and of re-incarnations, which bind together, like so many links of the same chain, all living creatures, from the most minute animal, even to those blessed beings to whom it is given to behold God in His glory; which gives brethren in the different planets to terrestrial humanity; which makes of the inhabitants of our globe a nation of the universe; which sees but one family in all the population of the worlds—a planetary family—whose every member may raise himself by his merits and his struggles, in the hierarchy of happiness, is supported by so many proofs. So many, indeed, that we are puzzled to choose among all the methods of demonstration which offer themselves in aid of it. To enumerate them all would unduly enlarge the dimensions of this work, so that we shall content ourselves with bringing forward the most striking.

Why are we on the earth? We did not ask to be placed there, we did not express a wish to be born. If we had been consulted, we should probably have objected to coming into this world at all, or at least we should have wished to appear there at some other epoch. We should probably have asked to be permitted to sojourn in some other planet than the Earth. Our globe is, indeed, a very disagreeable habitation. In consequence of its inclination on its axis, climate is very unpleasantly distributed. Either we must succumb to cold, if we are not artificially protected against it, or we must be terribly incommoded with heat. Regarded from the moral point of view, the conditions of humanity are very sad. Evil predominates in the world; vice is held almost everywhere in honour, and virtue is so ill-treated, that to be honest is, in this life, to be tolerably certain of evil fortune. Our affections are causes of anguish and tears. If, for a while, we enjoy the happiness of paternity, of love, of friendship, it is only to see the objects of our love torn from us by death, or separated from us by the accidents of a miserable life. The organs given us to be exercised in this life are heavy, coarse, subject to maladies. We are nailed to the earth, and our heavy mass can be moved only by fatiguing exertion. If there are men of powerful organization, gifted with a good constitution and robust health, how many are there who are infirm, idiots, deaf and dumb, blind from their birth, ricketty, and mad! My brother is handsome and well made, and I am ugly, feeble, ricketty, and hump-backed; nevertheless, we are both sons of the same mother. Some are born in opulence, others in the most hideous destitution. Why am I not a prince and a great lord, instead of being a poor toiler of the rebellious and ungrateful earth? Why was I born in Europe and in France, where, by means of art and civilization, life is rendered easy and endurable, instead of being born under the burning skies of the tropics, where, with a bestial snout, a black and oily skin, and woolly hair, I should have been exposed to the double torments of a deadly climate and social barbarism? Why is not one of the unfortunate African negroes in my place, comfortable and well off? We have done nothing, he and I, that our respective places on the earth should have been assigned to us. I have not merited the favour, he has not incurred the disgrace. What is the cause of this unequal division of frightful evils which fall heavily upon certain persons, and spare others? How have they who live in happy countries deserved this partiality of fate, while so many of their brethren are suffering and weeping in other regions of the world?

Certain men are endowed with all the gifts of the intellect; others, on the contrary, are devoid of intelligence, penetration, and memory. They stumble at every step in the difficult journey of life. Their narrow minds, their incomplete faculties, expose them to every kind of failure and misfortune. They cannot succeed in anything, and destiny seems to select them for the chosen victims of its most fatal blows. There are beings whose whole life, from their birth to their death, is a prolonged cry of suffering and despair. What crime have they committed? Why are they upon the earth? They have not asked to be born, and if they had been free, they would have entreated that this bitter cup might be removed from their lips. They are here below in spite of themselves, against their will. This is so true that some, in an excess of despair, sever the thread of their own life. They tear themselves away with their own hands from an existence which terrible suffering has rendered insupportable to them.

God would be unjust and wicked to impose so miserable a life upon beings who have done nothing to incur it, and who have not solicited it. But God is neither unjust nor wicked; the opposite qualities are the attribute of His perfect essence. Consequently, the presence of man on certain portions of the earth, and the unequal distribution of evil over our globe, are not to be explained. If any of my readers can show me a doctrine, a philosophy, a religion by which these difficulties can be resolved, I will tear up this book, and confess myself vanquished.

If, on the contrary, you admit the plurality of human existences and re-incarnations, that is to say the passage of the same soul into several different bodies, everything is wonderfully easily explained. Our presence in certain portions of the globe is no longer the effect of a caprice of fate, or the result of chance; it is simply a station of the long journey which we are taking throughout the worlds. Previous to our birth in this world we have lived either in the condition of superior animals, or that of man. Our actual existence is only the consequence of another, whether it be that we bear within ourselves the soul of a superior animal, which we must purify, perfect, and ennoble, during our sojourn on earth; or that, having already fulfilled an imperfect and evil existence, we are condemned to re-commence it under new obligations. In the latter case, the career of the man re-commences, because his soul is not yet sufficiently pure to rise to the rank of a superhuman being.

Our sojourn upon earth is then only a kind of trial, imposed upon us by nature, during which we must refine our souls, free them from earthly bonds, rid them of the defects which weigh them down, and hinder them from rising, in radiance, towards the ethereal spheres. Every ill-fulfilled human existence has to be recommenced. Thus, the school-boy who has worked hard, who has studied well, goes into a higher class at the end of the year; but if he has made no progress in his studies, he must go through his class again. Perverse men are, in our opinion, vicious beings who have had a previous life, and are obliged to live it over again. They must go through it again and again, until the day comes when their souls shall be fit to take higher rank in the hierarchy of creatures, that is to say, until they shall be fit to pass, after their death, into the condition of superhuman beings.

In proportion as the cause of our existence here below is obscure and even inexplicable according to ordinary ideas, it is simple and luminous in the light of the doctrine of the plurality of existences. We must add that this doctrine is conformable to the justice of God. In making earthly life a trial for man, God is equitable and good, like an earthly father. Is it not better to subject a soul to a trial which may begin over again if it have an unfortunate result, than to bind it to one condition, failure in which must involve the condemnation of the guilty person? It is better to offer the possibility of rehabilitation by his own efforts, by his personal struggles, to a fallen creature, than to utterly crush him, stained by his crimes and imperfections. The justice and the goodness of God are manifest in this paternal arrangement, much more than in the severe jurisdiction which would irretrievably condemn a soul after one single trial had resulted unfavourably.

If human life be a trial, if it be a period during which we are preparing for a new and happier existence, there is no need to look beyond that truth for an explanation of why we are on the earth, why we are living to-day rather than to-morrow, and in one latitude of our globe rather than in another; there is no need to ask why we are born in the earth, and not in Mercury, Saturn, or Mars. Whether we are living now, or are to live later, whether we have been born in the earth, in Mercury, or in Mars, whether we inhabit Europe or Africa,—all these things are utterly unimportant to our destiny. We are undergoing a period of preparation indispensably necessary to be accomplished before we pass into the superhuman condition; and the place, the moment of our transit, the country in which we sojourn, the planet which is assigned to us as the scene of this trial, are without any importance in the part which we have to play in accordance with the intentions of nature. We are making an immense journey through the worlds, and a short sojourn on the Earth makes a part of our vast itinerary. Whatever may be the corner of the universe in which we find ourselves we cannot escape the trial imposed upon us by God, a trial by strife and suffering, a period of moral and physical pain to which we must submit before we can be promoted in the hierarchy of creatures. The time, the place, the good or evil moral conditions ought therefore to be indifferent to us. What is needful for us is a brief sojourn on a planet in which this trial may be accomplished, and it may be accomplished on the Earth, or in Mars, or in Mercury, and on any spot of the Earth's surface one chooses to think of.

If, during the course of this trial, we meet with moral evil, if we see vice triumphant and virtue persecuted, if we see the innocent victims of the injustice, the cruelty, or the ignorance of man, we have no right to murmur against Providence, we have no right to utter maledictions against pain, to deplore the scandal of successful and triumphant crime, and of suffering and weeping virtue. We have no right to regret our bodily infirmities, the diseases which lay hold upon us on the Earth, and which afflict us all our lives, or to complain of the weakness of our minds, the decay of our faculties. All these conditions, which are inimical to earthly happiness, are a portion of the series of trials which we have to undergo here below. We ought to bless those evils, and be grateful to those sufferings, for they are the instruments of our eternal redemption, and the more piercing and bitter they are the sooner will come the hour of our deliverance, the happy moment when we shall leave this impure and filthy world which our feet have trodden for a while. Besides, justice will speedily be done. With brief delay the wicked shall be punished for his evil deeds by having to recommence a new existence here, while the good shall be elevated to the upper world, where a new, wide-ranging life awaits him, far more happy and more wise, in truer harmony with the aspirations of our nature than his previous and miserable existence here. Then we shall be born again, radiant and strong, with our memory, our feelings, and our liberty complete.

Thus difficulties vanish, and problems are solved: thus uncertainty vanishes away, and mysteries which no doctrine, no religion, no philosophy, could dissipate, and which almost made us doubt the justice of God, are cleared up. The doctrine of re-incarnations and prior existences explains everything, answers everything.

We pass on to one of the most interesting questions of the doctrine of the pre-existence of souls, the question of children who have died in infancy. What becomes of children who die at a few days old, or at the age of eight or ten months, or at their birth? Until after all these periods the human soul remains quite undeveloped; it is in almost the same rudimentary state as at the hour of its birth. What, then, is the fate of young children after their death? The doctrine of the plurality of existences simplifies this question. It admits that when an infant dies before it has lived one year (the period of dentition), its soul remains upon the earth, and does not pass, like that of a grown man, into the state of a superhuman being. The soul of an infant a year old is still in a rudimentary condition, almost as much so as at the moment of its birth. The soul of a child who dies at that age has to begin life over again, disengaging itself from the little corpse, it incarnates itself in another newly-born body, and after this fresh incarnation, it begins a second life.