полная версия

полная версияThe Crown of Wild Olive

214

I shall not henceforward number the exercises recommended; as they are distinguished only by increasing difficulty of subject, not by difference of method.

215

If you understand the principle of the stereoscope you will know why; if not, it does not matter; trust me for the truth of the statement, as I cannot explain the principle without diagrams and much loss of time.

216

If you can, get first the plates marked with a star. The letters mean as follows:—

a stands for architecture, including distant grouping of towns,

cottages, &c.

c clouds, including mist and aërial effects.

f foliage.

g ground, including low hills, when not rocky.

l effects of light.

m mountains, or bold rocky ground.

p power of general arrangement and effect.

q quiet water.

r running or rough water; or rivers, even if calm, when their line of

flow is beautifully marked.

From the England Series.

a c f r. Arundel.

a f l. Ashby de la Zouche.

a l q r. Barnard Castle.*

f m r. Bolton Abbey.

f g r. Buckfastleigh.*

a l p. Caernarvon.

c l q. Castle Upnor.

a f l. Colchester.

l q. Cowes.

c f p. Dartmouth Cove.

c l q. Flint Castle.*

a f g l. Knaresborough.*

m r. High Force of Tees.*

a f q. Trematon.

a f p. Lancaster.

c l m r. Lancaster Sands.*

a g f. Launceston.

c f l r. Leicester Abbey.

f r. Ludlow.

a f l. Margate.

a l q. Orford.

c p. Plymouth.

f. Powis Castle.

l m q. Prudhoe Castle.

f l m r. Chain Bridge over Tees.*

m q. Ulleswater.

f m. Valle Crucis.

From the Keepsake.

m p q. Arona.

m. Drachenfells.

f l. Marley.*

p. St. Germain en Laye.

l p q. Florence.

l m. Ballyburgh Ness.*

From the Bible Series.

f m. Mount Lebanon.

m. Rock of Moses at Sinai.

a l m. Jericho.

a c g. Joppa.

c l p q. Solomon's Pools.*

a l. Santa Saba.

a l. Pool of Bethesda.

From Scott's Works.

p r. Melrose.

f r. Dryburgh.*

c m. Glencoe.

c m. Loch Coriskin.

a l. Caerlaverock.

From the "Rivers of France."

a q. Château of Amboise, with large bridge on right.

l p r. Rouen, looking down the river, poplars on right.*

a l p. Rouen, with cathedral and rainbow, avenue on the left.

a p. Rouen Cathedral.

f p. Pont de l'Arche.

f l p. View on the Seine, with avenue.

a c p. Bridge of Meulan.

c g p r. Caudebec.*

217

As well;—not as minutely: the diamond cuts finer lines on the steel than you can draw on paper with your pen; but you must be able to get tones as even, and touches as firm.

218

See, for account of these plates, the Appendix on "Works to be studied."

219

This sketch is not of a tree standing on its head, though it looks like it. You will find it explained presently.

220

It is meant, I believe, for "Salt Hill."

221

I do not mean that you can approach Turner or Durer in their strength, that is to say, in their imagination or power of design. But you may approach them, by perseverance, in truth of manner.

222

The following are the most desirable plates:

Grande Chartreuse.

Æsacus and Hespérie.

Cephalus and Procris.

Source of Arveron.

Ben Arthur.

Watermill.

Hindhead Hill.

Hedging and Ditching.

Dumblane Abbey.

Morpeth.

Calais Pier.

Pembury Mill.

Little Devil's Bridge.

River Wye (not Wye and Severn).

Holy Island.

Clyde.

Lauffenbourg.

Blair Athol.

Alps from Grenoble.

Raglan. (Subject with quiet brook, trees, and castle on the right.)

If you cannot get one of these, any of the others will be serviceable, except only the twelve following, which are quite useless:—

1. Scene in Italy, with goats on a walled road, and trees above.

2. Interior of church.

3. Scene with bridge, and trees above; figures on left, one playing a pipe.

4. Scene with figure playing on tambourine.

5. Scene on Thames with high trees, and a square tower of a church seen through them.

6. Fifth Plague of Egypt.

7. Tenth Plague of Egypt.

8. Rivaulx Abbey.

9. Wye and Severn.

10. Scene with castle in centre, cows under trees on the left.

11. Martello Towers.

12. Calm.

It is very unlikely that you should meet with one of the original etchings; if you should, it will be a drawing-master in itself alone, for it is not only equivalent to a pen-and-ink drawing by Turner, but to a very careful one: only observe, the Source of Arveron, Raglan, and Dumblane were not etched by Turner; and the etchings of those three are not good for separate study, though it is deeply interesting to see how Turner, apparently provoked at the failure of the beginnings in the Arveron and Raglan, took the plates up himself, and either conquered or brought into use the bad etching by his marvellous engraving. The Dumblane was, however, well etched by Mr. Lupton, and beautifully engraved by him. The finest Turner etching is of an aqueduct with a stork standing in a mountain stream, not in the published series; and next to it, are the unpublished etchings of the Via Mala and Crowhurst. Turner seems to have been so fond of these plates that he kept retouching and finishing them, and never made up his mind to let them go. The Via Mala is certainly, in the state in which Turner left it, the finest of the whole series: its etching is, as I said, the best after that of the aqueduct. Figure 20., above, is part of another fine unpublished etching, "Windsor, from Salt Hill." Of the published etchings, the finest are the Ben Arthur, Æsacus, Cephalus, and Stone Pines, with the Girl washing at a Cistern; the three latter are the more generally instructive. Hindhead Hill, Isis, Jason, and Morpeth, are also very desirable.

223

You will find more notice of this point in the account of Harding's tree-drawing, a little farther on.

224

The impressions vary so much in colour that no brown can be specified.

225

You had better get such a photograph, even if you have a Liber print as well.

226

See the closing letter in this volume.

227

Bogue, Fleet Street. If you are not acquainted with Harding's works (an unlikely supposition, considering their popularity), and cannot meet with the one in question, the diagrams given here will enable you to understand all that is needful for our purposes.

228

I draw this figure (a young shoot of oak) in outline only, it being impossible to express the refinements of shade in distant foliage in a woodcut.

229

His lithographic sketches, those, for instance, in the Park and the Forest, and his various lessons on foliage, possess greater merit than the more ambitious engravings in his "Principles and Practice of Art." There are many useful remarks, however, dispersed through this latter work.

230

On this law you will do well, if you can get access to it, to look at the fourth chapter of the fourth volume of "Modern Painters."

231

The student may hardly at first believe that the perspective of buildings is of little consequence: but he will find it so ultimately. See the remarks on this point in the Preface.

232

It is a useful piece of study to dissolve some Prussian blue in water, so as to make the liquid definitely blue: fill a large white basin with the solution, and put anything you like to float on it, or lie in it; walnut shells, bits of wood, leaves of flowers, &c. Then study the effects of the reflections, and of the stems of the flowers or submerged portions of the floating objects, as they appear through the blue liquid; noting especially how, as you lower your head and look along the surface, you see the reflections clearly; and how, as you raise your head, you lose the reflections, and see the submerged stems clearly.

233

Respecting Architectural Drawing, see the notice of the works of Prout in the Appendix.

234

I give Rossetti this preëminence, because, though the leading Pre-Raphaelites have all about equal power over colour in the abstract, Rossetti and Holman Hunt are distinguished above the rest for rendering colour under effects of light; and of these two, Rossetti composes with richer fancy and with a deeper sense of beauty, Hunt's stern realism leading him continually into harshness. Rossetti's carelessness, to do him justice, is only in water-colour, never in oil.

235

All the degradation of art which was brought about, after the rise of the Dutch school, by asphaltum, yellow varnish, and brown trees, would have been prevented, if only painters had been forced to work in dead colour. Any colour will do for some people, if it is browned and shining; but fallacy in dead colour is detected on the instant. I even believe that whenever a painter begins to wish that he could touch any portion of his work with gum, he is going wrong.

It is necessary, however, in this matter, carefully to distinguish between translucency and lustre. Translucency, though, as I have said above, a dangerous temptation, is, in its place, beautiful; but lustre, or shininess, is always, in painting, a defect. Nay, one of my best painter-friends (the "best" being understood to attach to both divisions of that awkward compound word), tried the other day to persuade me thatlustre was an ignobleness in anything; and it was only the fear of treason to ladies' eyes, and to mountain streams, and to morning dew, which kept me from yielding the point to him. One is apt always to generalise too quickly in such matters; but there can be no question that lustre is destructive of loveliness in colour, as it is of intelligibility in form. Whatever may be the pride of a young beauty in the knowledge that her eyes shine (though perhaps even eyes are most beautiful in dimness), she would be sorry if her cheeks did; and which of us would wish to polish a rose?

236

But not shiny or greasy. Bristol board, or hot-pressed imperial, or grey paper that feels slightly adhesive to the hand, is best. Coarse, gritty, and sandy papers are fit only for blotters and blunderers; no good draughtsman would lay a line on them. Turner worked much on a thin tough paper, dead in surface; rolling up his sketches in tight bundles that would go deep into his pockets.

237

I insist upon this unalterability of colour the more because I address you as a beginner, or an amateur; a great artist can sometimes get out of a difficulty with credit, or repent without confession. Yet even Titian's alterations usually show as stains on his work.

238

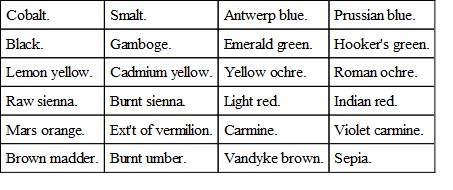

It is, I think, a piece of affectation to try to work with few colours; it saves time to have enough tints prepared without mixing, and you may at once allow yourself these twenty-four. If you arrange them in your colour-box in the order I have set them down, you will always easily put your finger on the one you want.

Antwerp blue and Prussian blue are not very permanent colours, but you need not care much about permanence in your own work as yet, and they are both beautiful; while Indigo is marked by Field as more fugitive still, and is very ugly. Hooker's green is a mixed colour, put in the box merely to save you loss of time in mixing gamboge and Prussian blue. No. 1. is the best tint of it. Violet carmine is a noble colour for laying broken shadows with, to be worked into afterwards with other colours.

If you wish to take up colouring seriously, you had better get Field's "Chromatography" at once; only do not attend to anything it says about principles or harmonies of colour; but only to its statements of practical serviceableness in pigments, and of their operations on each other when mixed, &c.

239

A more methodical, though, under general circumstances, uselessly prolix way, is to cut a square hole, some half an inch wide, in the sheet of cardboard, and a series of small circular holes in a slip of cardboard an inch wide. Pass the slip over the square opening, and match each colour beside one of the circular openings. You will thus have no occasion to wash any of the colours away. But the first rough method is generally all you want, as after a little practice, you only need to look at the hue through the opening in order to be able to transfer it to your drawing at once.

240

If colours were twenty times as costly as they are, we should have many more good painters. If I were Chancellor of the Exchequer I would lay a tax of twenty shillings a cake on all colours except black, Prussian blue, Vandyke brown, and Chinese white, which I would leave for students. I don't say this jestingly; I believe such a tax would do more to advance real art than a great many schools of design.

241

I say modern, because Titian's quiet way of blending colours, which is the perfectly right one, is not understood now by any artist. The best colour we reach is got by stippling; but this not quite right.

242

The worst general character that colour can possibly have is a prevalent tendency to a dirty yellowish green, like that of a decaying heap of vegetables; this colour is accurately indicative of decline or paralysis in missal-painting.

243

That is to say, local colour inherent in the object. The gradations of colour in the various shadows belonging to various lights exhibit form, and therefore no one but a colourist can ever draw forms perfectly (see "Modern Painters," vol. iv. chap. iii. at the end); but all notions of explaining form by superimposed colour, as in architectural mouldings, are absurd. Colour adorns form, but does not interpret it. An apple is prettier, because it is striped, but it does not look a bit rounder; and a cheek is prettier because it is flushed, but you would see the form of the cheek bone better if it were not. Colour may, indeed, detach one shape from another, as in grounding a bas-relief, but it always diminishes the appearance of projection, and whether you put blue, purple, red, yellow, or green, for your ground, the bas-relief will be just as clearly or just as imperfectly relieved, as long as the colours are of equal depth. The blue ground will not retire the hundredth part of an inch more than the red one.

244

See, however, at the close of this letter, the notice of one more point connected with the management of colour, under the head "Law of Harmony."

245

See farther, on this subject, "Modern Painters," vol. iv. chap. viii § 6.

246

"In general, throughout Nature, reflection and repetition are peaceful things, associated with the idea of quiet succession in events, that one day should be like another day, or one history the repetition of another history, being more or less results of quietness, while dissimilarity and non-succession are results of interference and disquietude. Thus, though an echo actually increases the quantity of sound heard, its repetition of the note or syllable gives an idea of calmness attainable in no other way; hence also the feeling of calm given to a landscape by the voice of a cuckoo."

247

This is obscure in the rude woodcut, the masts being so delicate that they are confused among the lines of reflection. In the original they have orange light upon them, relieved against purple behind.

248

The cost of art in getting a bridge level is always lost, for you must get up to the height of the central arch at any rate, and you only can make the whole bridge level by putting the hill farther back, and pretending to have got rid of it when you have not, but have only wasted money in building an unnecessary embankment. Of course, the bridge should not be difficultly or dangerously steep, but the necessary slope, whatever it may be, should be in the bridge itself, as far as the bridge can take it, and not pushed aside into the approach, as in our Waterloo road; the only rational excuse for doing which is that when the slope must be long it is inconvenient to put on a drag at the top of the bridge, and that any restiveness of the horse is more dangerous on the bridge than on the embankment. To this I answer: first, it is not more dangerous in reality, though it looks so, for the bridge is always guarded by an effective parapet, but the embankment is sure to have no parapet, or only a useless rail; and secondly, that it is better to have the slope on the bridge, and make the roadway wide in proportion, so as to be quite safe, because a little waste of space on the river is no loss, but your wide embankment at the side loses good ground; and so my picturesque bridges are right as well as beautiful, and I hope to see them built again some day, instead of the frightful straight-backed things which we fancy are fine, and accept from the pontifical rigidities of the engineering mind.

249

I cannot waste space here by reprinting what I have said in other books: but the reader ought, if possible, to refer to the notices of this part of our subject in "Modern Painters," vol. iv. chap. xviii., and "Stones of Venice," vol. iii. chap. i. § 8.

250

If you happen to be reading at this part of the book, without having gone through any previous practice, turn back to the sketch of the ramification of stone pine, Fig. 4. page 30., and examine the curves of its boughs one by one, trying them by the conditions here stated under the heads A. and B.

251

The reader, I hope, observes always that every line in these figures is itself one of varying curvature, and cannot be drawn by compasses.

252

I hope the reader understands that these woodcuts are merely facsimiles of the sketches I make at the side of my paper to illustrate my meaning as I write—often sadly scrawled if I want to get on to something else. This one is really a little too careless; but it would take more time and trouble to make a proper drawing of so odd a boat than the matter is worth. It will answer the purpose well enough as it is.

253

Imperfect vegetable form I consider that which is in its nature dependent, as in runners and climbers; or which is susceptible of continual injury without materially losing the power of giving pleasure by its aspect, as in the case of the smaller grasses. I have not, of course, space here to explain these minor distinctions, but the laws above stated apply to all the more important trees and shrubs likely to be familiar to the student.

254

There is a very tender lesson of this kind in the shadows of leaves upon the ground; shadows which are the most likely of all to attract attention, by their pretty play and change. If you examine them, you will find that the shadows do not take the forms of the leaves, but that, through each interstice, the light falls, at a little distance, in the form of a round or oval spot; that is to say, it produces the image of the sun itself, cast either vertically or obliquely, in circle or ellipse according to the slope of the ground. Of course the sun's rays produce the same effect, when they fall through any small aperture: but the openings between leaves are the only ones likely to show it to an ordinary observer, or to attract his attention to it by its frequency, and lead him to think what this type may signify respecting the greater Sun; and how it may show us that, even when the opening through which the earth receives light is too small to let us see the Sun himself, the ray of light that enters, if it comes straight from Him, will still bear with it His image.

255

In the smaller figure (32.), it will be seen that this interruption is caused by a cart coming down to the water's edge; and this object is serviceable as beginning another system of curves leading out of the picture on the right, but so obscurely drawn as not to be easily represented in outline. As it is unnecessary to the explanation of our point here, it has been omitted in the larger diagram, the direction of the curve it begins being indicated by the dashes only.

256

Both in the Sketches in Flanders and Germany.

257

If you happen to meet with the plate of Durer's representing a coat of arms with a skull in the shield, note the value given to the concave curves and sharp point of the helmet by the convex leafage carried round it in front; and the use of the blank white part of the shield in opposing the rich folds of the dress.

258

Turner hardly ever, as far as I remember, allows a strong light to oppose a full dark, without some intervening tint. His suns never set behind dark mountains without a film of cloud above the mountain's edge.

259

"A prudent chief not always must displayHis powers in equal ranks and fair array,But with the occasion and the place comply,Conceal his force; nay, seem sometimes to fly.Those oft are stratagems which errors seem,Nor is it Homer nods, but we that dream."Essay on Criticism.260

I am describing from a MS., circa 1300, of Gregory's "Decretalia" in my own possession.

261

One of the most wonderful compositions of Tintoret in Venice, is little more than a field of subdued crimson, spotted with flakes of scattered gold. The upper clouds in the most beautiful skies owe great part of their power to infinitude of division; order being marked through this division.

262

I fully believe that the strange grey gloom, accompanied by considerable power of effect, which prevails in modern French art must be owing to the use of this mischievous instrument; the French landscape always gives me the idea of Nature seen carelessly in the dark mirror, and painted coarsely, but scientifically, through the veil of its perversion.

263

Various other parts of this subject are entered into, especially in their bearing on the ideal of painting, in "Modern Painters," vol. iv. chap. iii.

264

In all the best arrangements of colour, the delight occasioned by their mode of succession is entirely inexplicable, nor can it be reasoned about; we like it just as we like an air in music, but cannot reason any refractory person into liking it, if they do not: and yet there is distinctly a right and a wrong in it, and a good taste and bad taste respecting it, as also in music.

265