полная версия

полная версияThe Crown of Wild Olive

On one side I say, it is the root of all simplicity. If you were for some prolonged period to study Greek sculpture exclusively in the Elgin Room of the British Museum, and were then suddenly transported to the Hôtel de Cluny, or any other museum of Gothic and barbarian workmanship, you would imagine the Greeks were the masters of all that was grand, simple, wise, and tenderly human, opposed to the pettiness of the toys of the rest of mankind.

202. On one side of their work they are so. From all vain and mean decoration—all weak and monstrous error, the Greeks rescue the forms of man and beast, and sculpture them in the nakedness of their true flesh, and with the fire of their living soul. Distinctively from other races, as I have now, perhaps to your weariness, told you, this is the work of the Greek, to give health to what was diseased, and chastisement to what was untrue. So far as this is found in any other school, hereafter, it belongs to them by inheritance from the Greeks, or invests them with the brotherhood of the Greek. And this is the deep meaning of the myth of Dædalus as the giver of motion to statues. The literal change from the binding together of the feet to their separation, and the other modifications of action which took place, either in progressive skill, or often, as the mere consequence of the transition from wood to stone, (a figure carved out of one wooden log must have necessarily its feet near each other, and hands at its sides), these literal changes are as nothing, in the Greek fable, compared to the bestowing of apparent life. The figures of monstrous gods on Indian temples have their legs separate enough; but they are infinitely more dead than the rude figures at Branchidæ sitting with their hands on their knees. And, briefly, the work of Dædalus is the giving of deceptive life, as that of Prometheus the giving of real life; and I can put the relation of Greek to all other art, in this function, before you in easily compared and remembered examples.

203. Here, on the right, in Plate XX., is an Indian bull, colossal, and elaborately carved, which you may take as a sufficient type of the bad art of all the earth. False in form, dead in heart, and loaded with wealth, externally. We will not ask the date of this; it may rest in the eternal obscurity of evil art, everywhere and for ever. Now, besides this colossal bull, here is a bit of Dædalus work, enlarged from a coin not bigger than a shilling: look at the two together, and you ought to know, henceforward, what Greek art means, to the end of your days.

204. In this aspect of it then, I say, it is the simplest and nakedest of lovely veracities. But it has another aspect, or rather another pole, for the opposition is diametric. As the simplest, so also it is the most complex of human art. I told you in my fifth Lecture, showing you the spotty picture of Velasquez, that an essential Greek character is a liking for things that are dappled. And you cannot but have noticed how often and how prevalently the idea which gave its name to the Porch of Polygnotus, "στοα ποικιλη," occurs to the Greeks as connected with the finest art. Thus, when the luxurious city is opposed to the simple and healthful one, in the second book of Plato's Polity, you find that, next to perfumes, pretty ladies, and dice, you must have in it "ποικιλια," which observe, both in that place and again in the third book, is the separate art of joiners' work, or inlaying; but the idea of exquisitely divided variegation or division, both in sight and sound—the "ravishing division to the lute," as in Pindar's "ροικιλοι ὑμνοι"—runs through the compass of all Greek art-description; and if, instead of studying that art among marbles you were to look at it only on vases of a fine time, (look back, for instance, to Plate IV. here), your impression of it would be, instead of breadth and simplicity, one of universal spottiness and chequeredness, "εν ανγεων Ἑρκεσιν παμποικιλοις;" and of the artist's delighting in nothing so much as in crossed or starred or spotted things; which, in right places, he and his public both do unlimitedly. Indeed they hold it complimentary even to a trout, to call him a "spotty." Do you recollect the trout in the tributaries of the Ladon, which Pausanias says were spotted, so that they were like thrushes and which, the Arcadians told him, could speak? In this last ποικιλια, however, they disappointed him. "I, indeed, saw some of them caught," he says, "but I did not hear any of them speak, though I waited beside the river till sunset."

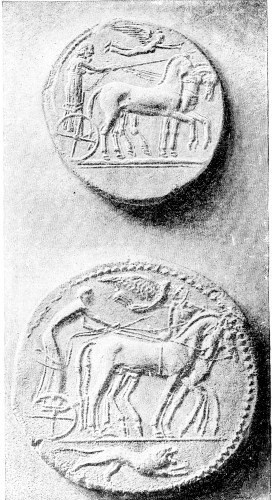

Plate XXI.—The Beginnings of Chivalry.

205. I must sum roughly now, for I have detained you too long.

The Greeks have been thus the origin not only of all broad, mighty, and calm conception, but of all that is divided, delicate, and tremulous; "variable as the shade, by the light quivering aspen made." To them, as first leaders of ornamental design, belongs, of right, the praise of glistenings in gold, piercings in ivory, stainings in purple, burnishings in dark blue steel; of the fantasy of the Arabian roof—quartering of the Christian shield,—rubric and arabesque of Christian scripture; in fine, all enlargement, and all diminution of adorning thought, from the temple to the toy, and from the mountainous pillars of Agrigentum to the last fineness of fretwork in the Pisan Chapel of the Thorn.

And in their doing all this, they stand as masters of human order and justice, subduing the animal nature guided by the spiritual one, as you see the Sicilian Charioteer stands, holding his horse-reins, with the wild lion racing beneath him, and the flying angel above, on the beautiful coin of early Syracuse; (lowest in Plate XXI).

And the beginnings of Christian chivalary were in that Greek bridling of the dark and the white horses.

206. Not that a Greek never made mistakes. He made as many as we do ourselves, nearly;—he died of his mistakes at last—as we shall die of them; but so far he was separated from the herd of more mistaken and more wretched nations—so far as he was Greek—it was by his rightness. He lived, and worked, and was satisfied with the fatness of his land, and the fame of his deeds, by his justice, and reason, and modesty. He became Græculus esuriens, little, and hungry, and every man's errand-boy, by his iniquity, and his competition, and his love of talk. But his Græcism was in having done, at least at one period of his dominion, more than anybody else, what was modest, useful, and eternally true; and as a workman, he verily did, or first suggested the doing of, everything possible to man.

Take Dædalus, his great type of the practically executive craftsman, and the inventor of expedients in craftsmanship, (as distinguished from Prometheus, the institutor of moral order in art). Dædalus invents,—he, or his nephew,—

The potter's wheel, and all work in clay;

The saw, and all work in wood;

The masts and sails of ships, and all modes of motion; (wings only proving too dangerous!)

The entire art of minute ornament;

And the deceptive life of statues.

By his personal toil, he involves the fatal labyrinth for Minos; builds an impregnable fortress for the Agrigentines; adorns healing baths among the wild parsley fields of Selinus; buttresses the precipices of Eryx, under the temple of Aphrodite; and for her temple itself—finishes in exquisiteness the golden honeycomb.

207. Take note of that last piece of his art: it is connected with many things which I must bring before you when we enter on the study of architecture. That study we shall begin at the foot of the Baptistery of Florence, which, of all buildings known to me, unites the most perfect symmetry with the quaintest ροικιλια. Then, from the tomb of your own Edward the Confessor, to the farthest shrine of the opposite Arabian and Indian world, I must show you how the glittering and iridescent dominion of Dædalus prevails; and his ingenuity in division, interposition, and labyrinthine sequence, more widely still. Only this last summer I found the dark red masses of the rough sandstone of Furness Abbey had been fitted by him, with no less pleasure than he had in carving them, into wedged hexagons—reminiscences of the honeycomb of Venus Erycina. His ingenuity plays around the framework of all the noblest things; and yet the brightness of it has a lurid shadow. The spot of the fawn, of the bird, and the moth, may be harmless. But Dædalus reigns no less over the spot of the leopard and snake. That cruel and venomous power of his art is marked, in the legends of him, by his invention of the saw from the serpent's tooth; and his seeking refuge, under blood-guiltiness, with Minos, who can judge evil, and measure, or remit, the penalty of it, but not reward good: Rhadamanthus only can measure that; but Minos is essentially the recognizer of evil deeds "conoscitor delle peccata," whom, therefore, you find in Dante under the form of the ερπετον. "Cignesi con la coda tante volte, quantunque gradi vuol che giu sia messa."

And this peril of the influence of Dædalus is twofold; first in leading us to delight in glitterings and semblances of things, more than in their form, or truth;—admire the harlequin's jacket more than the hero's strength; and love the gilding of the missal more than its words;—but farther, and worse, the ingenuity of Dædalus may even become bestial, an instinct for mechanical labour only, strangely involved with a feverish and ghastly cruelty:—(you will find this distinct in the intensely Dædal work of the Japanese); rebellious, finally, against the laws of nature and honour, and building labyrinths for monsters,—not combs for bees.

208. Gentlemen, we of the rough northern race may never, perhaps, be able to learn from the Greek his reverence for beauty: but we may at least learn his disdain of mechanism:—of all work which he felt to be monstrous and inhuman in its imprudent dexterities.

We hold ourselves, we English, to be good workmen. I do not think I speak with light reference to recent calamity, (for I myself lost a young relation, full of hope and good purpose, in the foundered ship London,) when I say that either an Æginetan or Ionian shipwright built ships that could be fought from, though they were under water; and neither of them would have been proud of having built one that would fill and sink helplessly if the sea washed over her deck, or turn upside down if a squall struck her topsail.

Believe me, gentlemen, good workmanship consists in continence and common sense, more than in frantic expatiation of mechanical ingenuity; and if you would be continent and rational, you had better learn more of Art than you do now, and less of Engineering. What is taking place at this very hour,138 among the streets, once so bright, and avenues once so pleasant, of the fairest city in Europe, may surely lead us all to feel that the skill of Dædalus, set to build impregnable fortresses, is not so wisely applied as in framing the τρητον πονου—the golden honeycomb.

THE FUTURE OF ENGLAND

(Delivered at the R. A. Institution, Woolwich, December 14, 1869.)I would fain have left to the frank expression of the moment, but fear I could not have found clear words—I cannot easily find them, even deliberately,—to tell you how glad I am, and yet how ashamed, to accept your permission to speak to you. Ashamed of appearing to think that I can tell you any truth which you have not more deeply felt than I; but glad in the thought that my less experience, and way of life sheltered from the trials, and free from the responsibilities of yours, may have left me with something of a child's power of help to you; a sureness of hope, which may perhaps be the one thing that can be helpful to men who have done too much not to have often failed in doing all that they desired. And indeed, even the most hopeful of us, cannot but now be in many things apprehensive. For this at least we all know too well, that we are on the eve of a great political crisis, if not of political change. That a struggle is approaching between the newly-risen power of democracy and the apparently departing power of feudalism; and another struggle, no less imminent, and far more dangerous, between wealth and pauperism. These two quarrels are constantly thought of as the same. They are being fought together, and an apparently common interest unites for the most part the millionaire with the noble, in resistance to a multitude, crying, part of it for bread and part of it for liberty.

And yet no two quarrels can be more distinct. Riches—so far from being necessary to noblesse—are adverse to it. So utterly adverse, that the first character of all the Nobilities which have founded great dynasties in the world is to be poor;—often poor by oath—always poor by generosity. And of every true knight in the chivalric ages, the first thing history tells you is, that he never kept treasure for himself.

Thus the causes of wealth and noblesse are not the same; but opposite. On the other hand, the causes of anarchy and of the poor are not the same, but opposite. Side by side, in the same rank, are now indeed set the pride that revolts against authority, and the misery that appeals against avarice. But, so far from being a common cause, all anarchy is the forerunner of poverty, and all prosperity begins in obedience. So that thus, it has become impossible to give due support to the cause of order, without seeming to countenance injury; and impossible to plead justly the claims of sorrow, without seeming to plead also for those of license.

Let me try, then, to put in very brief terms, the real plan of this various quarrel, and the truth of the cause on each side. Let us face that full truth, whatever it may be, and decide what part, according to our power, we should take in the quarrel.

First. For eleven hundred years, all but five, since Charlemagne set on his head the Lombard crown, the body of European people have submitted patiently to be governed; generally by kings—always by single leaders of some kind. But for the last fifty years they have begun to suspect, and of late they have many of them concluded, that they have been on the whole ill-governed, or misgoverned, by their kings. Whereupon they say, more and more widely, "Let us henceforth have no kings; and no government at all."

Now we said, we must face the full truth of the matter, in order to see what we are to do. And the truth is that the people have been misgoverned;—that very little is to be said, hitherto, for most of their masters—and that certainly in many places they will try their new system of "no masters:"—and as that arrangement will be delightful to all foolish persons, and, at first, profitable to all wicked ones,—and as these classes are not wanting or unimportant in any human society,—the experiment is likely to be tried extensively. And the world may be quite content to endure much suffering with this fresh hope, and retain its faith in anarchy, whatever comes of it, till it can endure no more.

Then, secondly. The people have begun to suspect that one particular form of this past misgovernment has been, that their masters have set them to do all the work, and have themselves taken all the wages. In a word, that what was called governing them, meant only wearing fine clothes, and living on good fare at their expense. And I am sorry to say, the people are quite right in this opinion also. If you inquire into the vital fact of the matter, this you will find to be the constant structure of European society for the thousand years of the feudal system; it was divided into peasants who lived by working; priests who lived by begging; and knights who lived by pillaging; and as the luminous public mind becomes gradually cognizant of these facts, it will assuredly not suffer things to be altogether arranged that way any more; and the devising of other ways will be an agitating business; especially because the first impression of the intelligent populace is, that whereas, in the dark ages, half the nation lived idle, in the bright ages to come, the whole of it may.

Now, thirdly—and here is much the worst phase of the crisis. This past system of misgovernment, especially during the last three hundred years, has prepared, by its neglect, a class among the lower orders which it is now peculiarly difficult to govern. It deservedly lost their respect—but that was the least part of the mischief. The deadly part of it was, that the lower orders lost their habit, and at last their faculty, of respect;—lost the very capability of reverence, which is the most precious part of the human soul. Exactly in the degree in which you can find creatures greater than yourself, to look up to, in that degree, you are ennobled yourself, and, in that degree, happy. If you could live always in the presence of archangels, you would be happier than in that of men; but even if only in the company of admirable knights and beautiful ladies, the more noble and bright they were, and the more you could reverence their virtue the happier you would be. On the contrary, if you were condemned to live among a multitude of idiots, dumb, distorted and malicious, you would not be happy in the constant sense of your own superiority. Thus all real joy and power of progress in humanity depend on finding something to reverence; and all the baseness and misery of humanity begin in a habit of disdain. Now, by general misgovernment, I repeat, we have created in Europe a vast populace, and out of Europe a still vaster one, which has lost even the power and conception of reverence;139 —which exists only in the worship of itself—which can neither see anything beautiful around it, nor conceive anything virtuous above it; which has, towards all goodness and greatness, no other feelings than those of the lowest creatures—fear, hatred, or hunger a populace which has sunk below your appeal in their nature, as it has risen beyond your power in their multitude;—whom you can now no more charm than you can the adder, nor discipline, than you can the summer fly.

It is a crisis, gentlemen; and time to think of it. I have roughly and broadly put it before you in its darkness. Let us look what we may find of light.

Only the other day, in a journal which is a fairly representative exponent of the Conservatism of our day, and for the most part not at all in favor of strikes or other popular proceedings; only about three weeks since, there was a leader, with this, or a similar, title—"What is to become of the House of Lords?" It startled me, for it seemed as if we were going even faster than I had thought, when such a question was put as a subject of quite open debate, in a journal meant chiefly for the reading of the middle and upper classes. Open or not—the debate is near. What is to become of them? And the answer to such question depends first on their being able to answer another question—"What is the use of them!" For some time back, I think the theory of the nation has been, that they are useful as impediments to business, so as to give time for second thoughts. But the nation is getting impatient of impediments to business; and certainly, sooner or later, will think it needless to maintain these expensive obstacles to its humors. And I have not heard, either in public, or from any of themselves, a clear expression of their own conception of their use. So that it seems thus to become needful for all men to tell them, as our one quite clear-sighted teacher, Carlyle, has been telling us for many a year, that the use of the Lords of a country is to govern the country. If they answer that use, the country will rejoice in keeping them; if not, that will become of them which must of all things found to have lost their serviceableness.

Here, therefore, is the one question, at this crisis, for them, and for us. Will they be lords indeed, and give us laws—dukes indeed, and give us guiding—princes indeed, and give us beginning, of truer dynasty, which shall not be soiled by covetousness, nor disordered by iniquity? Have they themselves sunk so far as not to hope this? Are there yet any among them who can stand forward with open English brows, and say,—So far as in me lies, I will govern with my might, not for Dieu et mon Droit, but for the first grand reading of the war cry, from which that was corrupted, "Dieu et Droit?" Among them I know there are some—among you, soldiers of England, I know there are many, who can do this; and in you is our trust. I, one of the lower people of your country, ask of you in their name—you whom I will not any more call soldiers, but by the truer name of Knights;—Equites of England. How many yet of you are there, knights errant now beyond all former fields of danger—knights patient now beyond all former endurance; who still retain the ancient and eternal purpose of knighthood, to subdue the wicked, and aid the weak? To them, be they few or many, we English people call for help to the wretchedness, and for rule over the baseness, of multitudes desolate and deceived, shrieking to one another this new gospel of their new religion. "Let the weak do as they can, and the wicked as they will."

I can hear you saying in your hearts, even the bravest of you, "The time is past for all that." Gentlemen, it is not so. The time has come for more than all that. Hitherto, soldiers have given their lives for false fame, and for cruel power. The day is now when they must give their lives for true fame, and for beneficent power: and the work is near every one of you—close beside you—the means of it even thrust into your hands. The people are crying to you for command, and you stand there at pause, and silent. You think they don't want to be commanded; try them; determine what is needful for them—honorable for them; show it them, promise to bring them to it, and they will follow you through fire. "Govern us," they cry with one heart, though many minds. They can be governed still, these English; they are men still; not gnats, nor serpents. They love their old ways yet, and their old masters, and their old land. They would fain live in it, as many as may stay there, if you will show them how, there, to live;—or show them even, how, there, like Englishmen, to die.

"To live in it, as many as may!" How many do you think may? How many can? How many do you want to live there? As masters, your first object must be to increase your power; and in what does the power of a country consist? Will you have dominion over its stones, or over its clouds, or over its souls? What do you mean by a great nation, but a great multitude of men who are true to each other, and strong, and of worth? Now you can increase the multitude only definitely—your island has only so much standing room—but you can increase the worth indefinitely. It is but a little island;—suppose, little as it is, you were to fill it with friends? You may, and that easily. You must, and that speedily; or there will be an end to this England of ours, and to all its loves and enmities.

To fill this little island with true friends—men brave, wise, and happy! Is it so impossible, think you, after the world's eighteen hundred years of Christianity, and our own thousand years of toil, to fill only this little white gleaming crag with happy creatures, helpful to each other? Africa, and India, and the Brazilian wide-watered plain, are these not wide enough for the ignorance of our race? have they not space enough for its pain? Must we remain here also savage,—here at enmity with each other,—here foodless, houseless, in rags, in dust, and without hope, as thousands and tens of thousands of us are lying? Do not think it, gentlemen. The thought that it is inevitable is the last infidelity; infidelity not to God only, but to every creature and every law that He has made. Are we to think that the earth was only shaped to be a globe of torture; and that there cannot be one spot of it where peace can rest, or justice reign? Where are men ever to be happy, if not in England? by whom shall they ever be taught to do right, if not by you? Are we not of a race first among the strong ones of the earth; the blood in us incapable of weariness, unconquerable by grief? Have we not a history of which we can hardly think without becoming insolent in our just pride of it? Can we dare, without passing every limit of courtesy to other nations, to say how much more we have to be proud of in our ancestors than they? Among our ancient monarchs, great crimes stand out as monstrous and strange. But their valor, and, according to their understanding, their benevolence, are constant. The Wars of the Roses, which are as a fearful crimson shadow on our land, represent the normal condition of other nations; while from the days of the Heptarchy downwards we have had examples given us, in all ranks, of the most varied and exalted virtue; a heap of treasure that no moth can corrupt, and which even our traitorship, if we are to become traitors to it, cannot sully.