полная версия

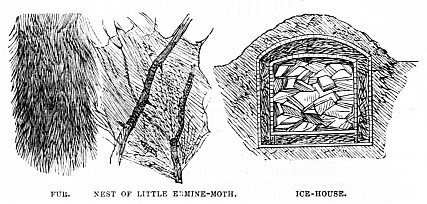

полная версияNature's Teachings

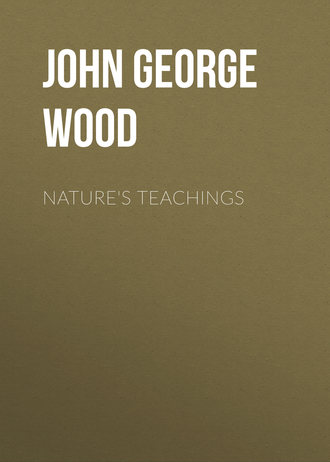

In summer-time he contents himself with a hut made of skins, and merely hangs a skin over the entrance by way of a door. But in the winter, when he is driven to his snow-house for shelter, he acts in a very different manner. Instead of merely cutting an aperture for a door in the side of the igloo, he constructs a long, low, arched tunnel, so small that no one can enter the igloo except by traversing this tunnel on his hands and knees. Sometimes a number of huts are connected with each other, one or two tunnels leading into the air, and the rest serving merely as passages from one hut to the other.

In Nature are several examples of tunnels constructed on the same principle.

There are, for instance, the curious nests of the Fairy Martin of Southern Australia (Hirundo Ariel), which bear a singular resemblance to oil-flasks, the body of the nest being rather globular, and the only entrance being through a tolerably long, tunnel-like neck.

Then there are the various Weaver-birds of Africa, with their long-necked nests. Some of these strange edifices look almost like horse-pistols suspended by the butt, so round is the nest, and so long and narrow is the tunnel-like entrance.

Passing to the insect world, we find the same principle carried out by the now familiar Mason-wasp (Odynerus murarius), some of whose nests are represented in the illustration.

This insect makes a burrow, and at the bottom of it deposits an egg, together with a number of little caterpillars on which the grub, when hatched, will feed. The mother Wasp is not allowed to pursue this task without taking precautions against the admission of enemies to her burrow, especially the ichneumon-flies. As may be inferred from its popular name, the Sand-wasp always selects a sandy spot for its burrow, and generally chooses a piece of tolerably hard sandstone, which it is able to bite into little pellets, aided by a kind of liquid which it secretes.

The following account of the manner in which the Mason-wasp forms and defends its home is taken from the invaluable “Insect Architecture,” by Rennie.

The author begins by describing the form and depth of the burrow, and the soil in which it is made. He then proceeds to show the wonderful manner in which the mother Wasp purveys food for the use of her future young whom she will never see. Guided by instinct, she places in the burrow exactly the number of caterpillars which the young Mason-wasp will have to consume before it attains its perfect condition. It is believed that she partially paralyzes them with her sting before placing them in the burrow. At all events, when they are once packed away, they never move, so that the tiny Wasp grub can feed upon them quite at its leisure.

Here is Rennie’s account of the Sand-wasp and her burrow-making:—

“When this wasp has detached a few grains of the moistened sand, it kneads them together into a pellet about the size of one of the seeds of a gooseberry.

“With the first pellet which it detaches, it lays the foundation of a round tower, as an outwork, immediately over the mouth of its nest. Every pellet which it afterwards carries off from the interior is added to the wall of this outer round tower, which advances in height as the hole in the sand increases in depth. Every two or three minutes, however, during these operations, it takes a short excursion, for the purpose probably of replenishing its store of fluid wherewith to moisten the sand. Yet so little time is lost, that Réaumur has seen a mason-wasp dig in an hour a hole the length of its body, and at the same time build as much of its round tower.

“For the greater part of its height this round tower is perpendicular, but towards the summit it bends into a curve, corresponding to the bend of the insect’s body, which, in all cases of insect architecture, is the model followed. The pellets which form the walls of the tower are not very nicely joined, and numerous vacuities are left between them, giving it the appearance of filigree-work.

“That it should be thus slightly built is not surprising, for it is intended as a temporary structure for protecting the insect while it is excavating its hole, and as a pile of materials, well arranged and ready at hand, for the completion of the interior building,—in the same way that workmen make a regular pile of bricks near the spot where they are going to build. This seems, in fact, to be the main design of the tower, which is taken down as expeditiously as it has been reared.

“Réaumur thinks, that by piling in the sand which has previously been dug out, the wasp intends to guard its progeny for a time from being exposed to the too violent heat of the sun; and he has sometimes even seen that there were not sufficient materials in the tower, in which case the wasp had recourse to the rubbish she had thrown out after the tower was completed. By raising a tower of the materials which she excavates, the wasp produces the same shelter from external heat as a human being would who chose to inhabit a deep cellar of a high house.

“She further protects her progeny from the ichneumon-fly, as the engineer constructs an outwork to render more difficult the approach of an enemy to the citadel. Réaumur has seen this indefatigable enemy of the wasp peep into the mouth of the tower, and then retreat, apparently frightened at the depth of the cell which she was anxious to invade.”

It is no wonder that the Sand-wasp should be so anxious to insure the safety of her nest, for her foes are multitudinous. Putting aside the ordinary Ichneumon-flies, we have the predatory Tachinæ, which are always hovering over such nests, and trying to deposit eggs therein. For many years I have been in the habit of receiving letters from novices in entomology, wanting to know whether I am aware that the common Housefly is in the habit of acting as a parasite. Of course, the writer has mistaken the Tachina for a house-fly, but I cannot regret the fact that some one has really begun to observe Nature, and not only to read books.

Doors and HingesHaving seen that both in Nature and Art the entrances to dwellings are guarded by tunnel-like approaches, we come naturally to another mode of guarding the entrance, namely, by a door moving on hinges. As to the multitudinous examples of doors and hinges in modern civilisation, we need hardly discuss them, except to show the exact analogies which occur in Art and Nature.

Doors moving on hinges are very plentiful in Nature, even where we should least expect them. Take, for example, an egg, especially the egg of an insect, and we shall see that it is just about the last object in which we should expect to find a hinged door. Yet, if the reader will refer to the illustration on page 7, he will see that the tiny eggs of the common Gnat, numerous as they may be, are each furnished with a door which opens as soon as the inmate is hatched, and allows the little larva to escape into the water.

Another still more remarkable instance of a hinged door in an egg is to be found in one of the Rotifers, or Wheel-Animalcules, so called because they possess an apparatus of movable cilia, which, when set in motion, looks exactly like a wheel running round and round. As the full-grown creature is barely one thirty-sixth of an inch in total length, the structure of its eggs must be infinitesimally beyond the range of human vision.

Yet, just as the telescope sets at partial defiance the vast spaces that intervene between our earth and her sister planets, so the microscope performs a similar task in the infinitesimally minute. And, under the all-revealing lens of the microscope, the little egg of the Brachionus, though absolutely invisible to the unaided eye, yields up its secrets.

Fortunately, the shell is so transparent that the interior of the egg can be seen through it as if it were a mere film of glass. The astonishing division and re-division of the yolk take place before our eyes, being divided first into two, then into four, then into eight, then into sixteen, then into thirty-two, and so on, until the whole mass of the yolk is cloven into divisions too numerous to count.

By degrees, the form of the young Brachionus is developed within the egg, even to the very teeth, which work away as persistently as if large stores of food were being passed through them.

When the young is ready to take its place in the world, a new development occurs, which has been well related by Mr. Gosse:—

“All these phenomena have appeared in the egg we are now watching; and at this moment you see the crystalline little prisoner, writhing and turning impatiently within its prison, striving to burst forth into liberty.

“Now, a crack, like a line of light, shoots round one end of the egg, and in an instant, the anterior third of the egg is forced off, and the wheels of the infant Brachionus are seen rotating as perfectly as if the little creature had had a year’s practice.

“Away it glides, the very image of its mother, and swims to some distance before it casts anchor, beginning an independent life. At the moment of escape of the young, the pushed-off lid of the egg resumes its place, and the egg appears nearly whole again, but empty and perfectly hyaline (i.e. all but transparent), with no evidence of its fracture, except a slight interruption of its outline, and a very faint line running across it.”

To pass from the egg to a more advanced stage in life. All practical entomologists have been greatly annoyed, in their earlier years of collecting, to lose larva after larva, from the attacks of Ichneumon-flies. It is certainly rather beyond the limits of ordinary patience to discover, watch over, and secure successfully a rare caterpillar, and then to find that it has been “stung” by an Ichneumon-fly.

The veteran entomologist, however, troubles himself very little about such minor misfortunes, and, as a rule, more than compensates for them by preserving the intrusive Ichneumon-fly, and giving in his diary full details of the insect on which it was parasitic, of the plant on which the caterpillar lived, the date of its appearance, and its numbers.

Now, there are many of these parasitic insects, notably those belonging to the genus Microgaster, which invariably make doors in their cocoons. I have now before me groups of cocoons made of the two commonest British species, namely, Microgaster glomeratus and Microgaster alvearius, and in both of them each tiny cocoon is furnished with a hemispherical, hinged door. I have also some exquisitely beautiful groups of Microgaster cocoons found in the West Indies. They are the purest white, shine with a satiny lustre, and are arranged round a hollow centre, much as if they had been gummed to the outside of a very large thimble. There are many hundreds of them, and every one has its little door still open as it was when the fully developed insect first made its escape.

Another curious example of a natural door may be seen by those who will look for it.

On plants infested with aphides, or “green blight,” as the gardeners quaintly term them, may often be seen dead aphides much larger than the rest, globular, brown, and shining. These aphides have been “stung,” as it is called, by a little Ichneumon-fly belonging to the genus Ophion, and having, like all its congeners, a flat and sickle-shaped abdomen. The egg which has been laid in the aphis soon hatches, and the young Ophion absorbs into itself all the juices of the aphis. It remains within the body of its involuntary host until it is fully developed, when it cuts a tiny, but beautifully perfect circular door in the skin, and emerges, leaving the door open and still attached by its little hinge.

Considering the small size of the aphis, and that the diameter of the door is only one-eighth of the length of the insect, the perfection of its form is really remarkable.

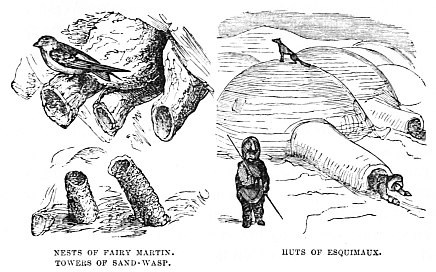

One of the achievements of modern Architecture is the Self-closing Door, especially where it must of necessity close by its own weight, and when the fitting is so exact, that even the most experienced eye can scarcely detect it. Such a door is to be found guarding the nest of the Trap-door Spiders, several species of which are found scattered over all the warm parts of the earth. A side view of one of these extraordinary nests is given in the accompanying illustration, and on the other side is the common trap-door of our cellars.

The Spiders which make these extraordinary dwellings generally begin by excavating a nearly perpendicular tunnel in the ground. They line it with a silken web, and construct a door which exactly fits the orifice, and which is bevelled so that it shall not sink too far, and thus betray itself. I have seen and handled one, where the burrow had been sunk among lichens and mosses, and the trap-door of the nest had been most ingeniously covered with the same growths. Although the surface of the slab of earth in which the nest was made is only a few inches square, it is almost impossible to detect the entrance, so admirably do the mosses on the door correspond with those outside it.

Almost invariably the nest is sunk in the ground, but I have a specimen sent to me from India, in which the Spider must absolutely have carried the clay to a fluted pillar, burrowed in it, and then made its beautiful habitation. The nest and its inhabitant were sent to me by an officer in the 108th Regiment, accompanied by the following letter:—

“The packet contains a large Spider and the upper portion of its peculiar nest, the history of which is as follows.

“On the thirtieth of last month (September, 1870), while searching for caterpillars on a bush growing close to one of the pillars of my verandah, which is a very low one, reaching to within a foot of the ground, I saw in part of the chunam masonry at the foot of the pillar what I at first sight took to be a couple of seeds sticking to a stone. On trying to pull one off, I found that it came up with ease, bringing with it what I thought was the stone.

“But I had scarcely got it up when it was smartly pulled back. This excited my curiosity, and I raised it again with a little force. I now saw, to my wonder and admiration, that what I had fancied was a stone was a small circular door with a pretty broad hinge, made all of silk; and then distinctly observed a large black spider dart down the hole to which the above door gave an entrance. But, not knowing the depth, I broke it.

“This piece I send to you, together with its original owner, who, at the beginning of my digging operations, ran up suddenly, shut the door in my face, and hung on to it like grim death when I tried to reopen it. He soon came away with the upper piece, still keeping the door resolutely closed.”

CHAPTER II.

WALLS, DOUBLE AND SINGLE.—PORCHES, EAVES, AND WINDOWS.—THATCH, SLATES, AND TILES

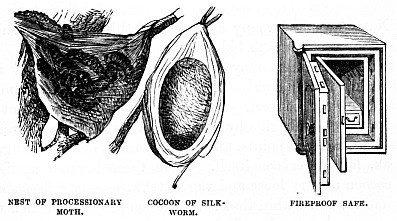

The Wall and its Materials.—Bricks as they are and might be.—Trade Unionism.—Double Walls and their Uses.—Double Clothing.—The Refrigerator.—Cooking Vessels.—Fire-proof Safes.—Cocoon of the Silkworm, and its treble Walls.—Nest of the Little Ermine, Processionary, Gold-tailed, and Brown-tailed Moths.—Mud Walls.—Nests of the Termite.—Porches, Eaves, and Windows.—Nests of the Myrapetra and an Indian Ant.—The Sociable Weaver-bird and its Nest.—Thatching.—Arms of the Orang-outan.—Japanese and Chinese Rain-cloaks.—Eggs of the Gold-tailed Moth.—Action of Fur.—Slates and Tiles.—Scales of Butterfly’s Wing.—Shell of Tortoise.—Scales of Manis, Fish, and Armadillo.

WE now come to the Walls of the house, in which there is more variety than might be imagined.

Take, for example, our modern houses of the “villa” type. They are nothing but the merest shells, made of the flimsiest imaginable materials. Some years ago, while walking through a suburb where some very showy houses were being built, I amused myself by going over them and testing them. There was scarcely a room in which I could not thrust an ordinary walking-stick through the wall. When they were “finished” and “pointed,” the houses looked beautiful, but their heat in summer, cold in winter, and moisture in wet weather, can easily be imagined, especially as the sand with which the mortar was mixed had been procured from the banks of a tidal river.

There is not the least necessity for such buildings. It is absurd to run up such edifices as that, and then charge £120 per annum for rent. The whole system is as rotten as the houses, and there is nothing but prejudice and trade-unionism to prevent our houses being cool in summer, warm in winter, and dry in all weathers.

It is well known that air is practically a non-conductor of heat, and that therefore a layer of air between two very slight walls is just as warm as if the wall had been made of solid stone. Now, there are several inventions whereby the present brick could be made half its present weight, twice its present strength, hard and smooth as earthenware, so that it could not absorb water like our common brick, and pierced with holes through which air could pass.

Unfortunately, however, there is a stringent rule among brickmakers and bricklayers that they are to play into each other’s hands, and that no bricklayer is to touch a brick which has not been made in some definite district. Should he do so, he is a marked man, and will stand but little chance of getting even a day’s work.

The power of the double wall may be seen in many ways. For example, in the old days of coaching, when one had to pass hour after hour on the roof of the coach, it was known by practical experience that double body linen, and two pairs of stockings, worn one over the other, formed the best preparation for the journey. The reason was, that air became entangled between the layers of fabric, and acted as a non-conductor of heat.

Another mode of utilising the principle of the double wall is seen in the refrigerators which add so much to the comfort of the household in a hot summer. The one principle of these refrigerators is, to keep a layer of air between the ice and the surrounding atmosphere. The same principle may be used in a reverse way, and heat be preserved instead of repelled. Those cooking-pots are now well known, where half-cooked meat can be inserted in the morning, and at luncheon-time be turned out quite hot and perfectly cooked. The fact is, that the vessels in question are covered with a very thick layer of felt. The felt, however, is only a device for entangling air, and a double wall would answer the purpose as well, if not better.

The now well-known fire-resisting safes are made on this principle, and after they have been for hours in a raging fire, and the outer case has become red-hot, the interior is quite safe, the papers uninjured, and even a watch continuing to go.

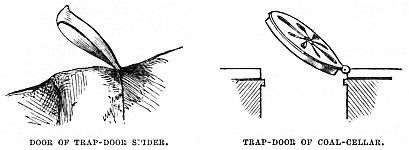

Then there is the ordinary Ice-house, a sketch of which is given in the illustration. A pit is first dug in the ground, and thickly lined with dry branches, straw, &c. The roof is constructed in the same manner, only the non-conducting power is increased by a thick coating of earth over the sticks and straw. The door, which is approached by a shelving cutting, is similarly protected, the covering only being removed when the door is opened.

I once made a very effective refrigerator out of two hampers, putting a small hamper inside a large one, and packing the space between them with straw.

In Nature we find many examples of this principle, which enables the inhabitants to bid defiance to frost.

A familiar example may be found in the cocoon of the common Silk-worm (Bombyx mori), and indeed in that of almost any silk-producing insect. When the caterpillar is about to make its cocoon, it begins by a number of rather strong threads attached to different points, and making a sort of scaffolding, so to speak, for the cocoon itself. Upon these is spun a slight outer cocoon of very loose and vague texture—the “floss silk” of commerce, and within that is the cocoon proper, in which the insect lies enclosed. It will be seen, therefore, that there are really three cocoons, one within the other, namely, the scaffold cocoon, the floss cocoon, and the silk cocoon itself, so that the inmate is protected from variations of temperature.

The cocoon of the emperor-moth, which has already been described, is made on the same principle.

There are several caterpillars which are social in their early stages, and which construct a common habitation. The Little Ermine-moth. (Hyponomeuta padella) affords a familiar example of this structure. The caterpillars are great roamers in search of food by day, and travel from branch to branch on their strong silken threads. At night, however, they return to a large white silken habitation which they have spun, and which they divide into many compartments, as may easily be seen by cutting the nest open with very sharp scissors. Within this habitation the caterpillars spin their separate cocoons, so that the system of double walls is thoroughly carried out.

There is another insect, very common on the Continent, but, happily for us, not introduced into England. It is called the Processionary Moth, from its curious habit of marching in exact lines, the head of the second caterpillar touching the tail of the first, and so on. These insects have likewise a common home, and spin their own separate cocoons within it.

There are two other sociable British Moths which make nests on a similar principle. These are the Gold-tailed Moth (Porthesia chrysorrhœa) and the Brown-tailed Moth (Porthesia auriflua). They are both beautifully white insects, but may easily be distinguished from each other, the Gold-tailed Moth having some brown-black spots on the upper wings, and a tuft of golden-yellow hairs at the end of the body; while the Brown-tailed Moth is without spots, and the tail-tuft is brown.

In habits they are very similar, and the description of the nest made by one will answer for that made by the other. I believe that broods of these two species have been known to construct a common nest. The nest is extremely variable in form, because it depends much on the number of twigs which it includes. Interiorly, it is divided into a considerable number of chambers, each containing one or several individuals.

As the caterpillars are hatched late in summer, they have to undergo the frosts of winter before they can attain their perfect state. Accordingly, before the winter-time comes on, they strengthen both the external walls and internal partitions of their nest, and then wait until the spring brings forth the leafage of the new year.

The nest is a beautiful structure, and I strongly recommend the reader to look for one in a hedgerow, take it home, and cut it up carefully. I would, however, advise him, if, like myself, he be subjected to a very sensitive skin, to be cautious in his handling of the nest. The hairs with which the pretty black, red, and white caterpillars are studded are irritant in the extreme.

I have several times suffered from them, and would much rather be severely stung by nettles than undergo the fierce irritation, mixed with dull heavy pain, which always accompanies the presence of these hairs. With me, as I suppose would be the case with persons of similar organization, these hairs cause large, hard tubercles to rise, just as if potatoes had been placed under the skin. The hairs of the Processionary Caterpillar have a similar effect, and in France the authorities have several times been obliged to close the public gardens for months, so severe was the pain which the caterpillars inflicted on persons who passed through the spots infested by them.

Mud WallsThere is a mode of wall-building which is much in vogue in some parts of England, and has much to commend itself. This is the Mud or Concrete Wall.

At first sight, the very name of a mud house gives an idea of poverty and misery, and is apt to be connected with hovels and pigsties. Mud walls, however, if properly built, are far warmer and drier than those of brick, and are even preferred to those of stone, when the latter can be easily and cheaply obtained. In Devonshire, for example, where even the cattle-sheds, or “linhays” (pronounced linny), and the pigsties are made of the rich red stone of the county, it is a common thing to see village houses built of mud. Sometimes the houses are built of stone to the height of some ten or twelve feet, and the upper parts made of mud.