полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 10, No. 60, October, 1862

RESULTS OF SANITARY REFORMS

The errors and losses which have been adverted to are not all constant nor universal: not every army is hungry or has bad cookery; not every one encamps in malarious spots, or sleeps in crowded tents, or is cold, wet, or overworked: but, so far as the internal history of military life has been revealed, they have been and are sufficiently frequent to produce a greater depression of force, more sickness, and a higher rate of mortality among the soldiery than are found to exist among civilians. Every failure to meet the natural necessities or wants of the animal body, in respect to food, air, cleanliness, and protection, has, in its own way, and in its due proportion, diminished the power that might otherwise have been created; and every misapplication has again reduced that vital capital which was already at a discount. These first bind the strong man, and then, exposing him to morbific influences, rob him of his health. Perhaps in none of the common affairs of the world do men allow so large a part of the power they raise and the means they gather for any purpose to be lost, before they reach their object and strike their final and effective blow, as the rulers of nations allow to be lost in the gathering and application of human force to the purposes of war. And this is mainly because those rulers do not study and regard the nature and conditions of the living machines with which they operate, and the vital forces that move them, as faithfully as men in civil life study and regard the conditions of the dead machines they use, and the powers of water and steam that propel them, and form their plans accordingly.

But it is satisfactory to know that great improvements have been made in this respect. From a careful and extended inquiry into the diseases of the army and their causes, it is manifest that they do not necessarily belong to the profession of war. Although sickness has been more prevalent, and death in consequence more frequent, in camps and military stations than in the dwellings of peace, this excess is not unavoidable, but may be mostly, if not entirely, prevented. Men are not more sick because they are soldiers and live apart from their homes, but because they are exposed to conditions or indulge in habits that would produce the same results in civil as in military life. Wherever civilians have fallen into these conditions and habits, they have suffered in the same way; and wherever the army has been redeemed from these, sickness and mortality have diminished, and the health and efficiency of the men have improved.

Great Britain has made and is still making great and successful efforts to reform the sanitary condition of her army. The improvement in the health of the troops in the Crimea in 1856 and 1857 has already been described. The reduction of the annual rate of mortality caused by disease, from 1,142 to 13 in a thousand, in thirteen months, opened the eyes of the Government to the real state of matters in the army, and to their own connection with it. They saw that the excess of sickness and death among the troops had its origin in circumstances and conditions which they could control, and then they began to feel the responsibility resting upon them for the health and life of their soldiers. On further investigation, they discovered that soldiers in active service everywhere suffered more by sickness and death than civilians at home, and then they very naturally concluded that a similar application of sanitary measures and enforcement of the sanitary laws would be as advantageous to the health and life of the men at all other places as in the Crimea. A thorough reform was determined upon, and carried out with signal success in all the military stations at home and abroad. "The late Lord Herbert, first in a royal commission, then in a commission for carrying out its recommendations, and lastly as Secretary of State for War in Lord Palmerston's administration, neglecting the enjoyments which high rank and a splendid fortune placed at his command, devoted himself to the sanitary reform of the army."75 He saw that the health of the soldiers was perilled more "by bad sanitary arrangements than by climate," and that these could be amended. "He had some courageous colleagues, among whom I must name as the foremost Florence Nightingale, who shares without diminishing his glory."76 Both of these great sanitary reformers sacrificed themselves for the good of the suffering and perishing soldier. "Lord Herbert died at the age of fifty-one, broken down by work so entirely that his medical attendants hardly knew to what to attribute his death."77 Although he probed the evil to the very bottom, and boldly laid bare the time-honored abuses, neglects, and ignorance of the natural laws, whence so much sickness had sprung to waste the army, yet he "did not think it enough to point out evils in a report; he got commissions of practical men to put an end to them."78 A new and improved code of medical regulations, and a new and rational system of sanitary administration, suited to the wants and liabilities of the human body, were devised and adopted for the British army, and their conditions are established and carried out with the most happy results.

These new systems connect with every corps of the army the means of protecting the health of the men, as well as of healing their diseases.

"The Medical Department of the British army includes,—

"1. Director-General, who is the sole responsible administrative head of the medical service.

"2. Three Heads of Departments, to aid the Director-General with their advice, and to work the routine-details.

"A Medical Head, to give advice and assistance on all subjects connected with the medical service and hospitals of the army.

"A Sanitary Head, to give advice and assistance on all subjects connected with the hygiene of the army.

"A Statistical Head, who will keep the medical statistics, case-books, meteorological registers," etc.79

Besides these medical officers, there are an Inspector-General of Hospitals, a Deputy Inspector-General of Hospitals, Staff and Regimental Surgeons, Staff and Regimental Assistant-Surgeons, and Apothecaries.

The British army is plentifully supplied with these medical officers. For the army of 118,000 men there were provided one thousand and seventy-five medical officers under full pay in 1859. Four hundred and seventy surgeons and assistant-surgeons were attached to the hundred regiments of infantry.80

It is made the duty of the medical officer to keep constant watch over all the means and habits of life among the troops,—"to see that all regulations for protecting the health of troops, in barracks, garrisons, stations, or camps, are duly observed." "He is to satisfy himself as to the sanitary condition of barracks," "as to their cleanliness, within and without, their ventilation, warming, and lighting," "as to the drainage, ash-pits, offal," etc. "He is to satisfy himself that the rations are good, that the kitchen-utensils are sufficient and in good order, and that the cooking is sufficiently varied."81

Nothing in the condition, circumstances, or habits of the men, that can affect their health, must be allowed to escape the notice of these medical officers.

In every plan for the location or movement of any body of troops, it is made the duty of the principal medical officer first to ascertain the effect which such movement or location will have upon the men, and advise the commander accordingly. It is his duty, also, to inspect all camp-sites and "give his opinion in writing on the salubrity or otherwise of the proposed position, with any recommendations he may have to make respecting the drainage, preparation of the ground, distance of the tents or huts from each other, the number of men to be placed in each tent or hut, the state of cleanliness, ventilation, and water-supply."82 "The sanitary officer shall keep up a daily inspection of the whole camp, and especially inform himself as to the health of the troops, and of the appearance of any zymotic disease among them; and he shall immediately, on being informed of the appearance of any such disease, examine into the cause of the same, whether such disease proceed from, or is aggravated by, sanitary defects in cleansing, drainage, nuisances, overcrowding, defective ventilation, bad or deficient water supply, dampness, marshy ground, or from any other local cause, or from bad or deficient food, intemperance, unwholesome liquors, fruit, defective clothing or shelter, exposure, fatigue, or any other cause, and report immediately to the commander of the forces, on such causes, and the remedial measures he has to propose for their removal." "And he shall report at least daily on the progress or decline of the disease, and on the means adopted for the removal of its causes."83

Thus the British army is furnished with the best sanitary instruction the nation can afford, to guide the officers and show the men how to live, and sustain their strength for the most effective labor in the service of the country.

To make this system of vigilant watchfulness over the health of the men the more effectual, the medical officer of each corps is required to make weekly returns to the principal medical officer of the command, and this principal officer makes monthly returns to the central office at London. These weekly and monthly returns include all the matters that relate to the health of the troops, "to the sanitary condition of the barracks, quarters, hospitals, the rations, clothing, duties, etc., of the troops, and the effects of these on their health."84

Under these new regulations, the exact condition of the army everywhere is always open to the eyes of medical and sanitary officers, and they are made responsible for the health of the soldiers. The consequence has been a great improvement in the condition and habits of the men. Camps have been better located and arranged. Food is better supplied. Cooking is more varied, and suited to the digestive powers. The old plan of boiling seven days in the week is abolished, and baking, stewing, and other more wholesome methods of preparation are adopted in the army-kitchens, with very great advantage to the health of the men and to the efficiency of the military service. Sickness has diminished and mortality very greatly lessened, and the most satisfactory evidence has been given from all the stations of the British army at home and abroad, that the great excess of disease and death among the troops over those of civilians at home is needless, and that health and life are measured out to the soldier, as well as to the citizen, according to the manner in which he fulfils or is allowed to fulfil the conditions established by Nature for his being here.

The last army medical report shows the amount and rate of sickness and mortality of every corps, both in the year 1859, under the new system of watchfulness and proper provision, and at a former period, under the old régime of neglect.

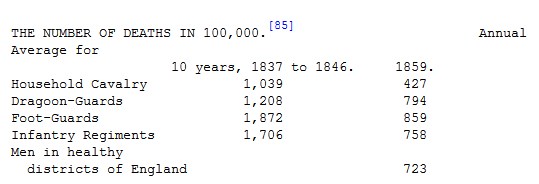

85 Report of the Army Medical Department for 1859, p. 6.

The Foot-Guards, which lost annually 1,415 from diseases of the chest before the reform, lost only 538 in 100,000 from the same cause in 1859.85

Among the infantry of the line, the annual attacks of fever were reduced to a little more than one-third, and the deaths from this cause to two-fifths of their former ratio. The cases of zymotic disease were diminished 33 per cent., and the mortality from this class of maladies was reduced 68 per cent.86

The same happy accounts of improvement come from every province and every military station where the British Government has placed its armies.

Our present army is in better condition than those of other times and other nations; and more and more will be done for this end. The Government has already admitted the Sanitary Commission into a sort of copartnership in the management of the army, and hereafter the principles of this excellent and useful association will be incorporated with, and become an inseparable part of, the machinery of war, to be conducted by the same hands that direct the movements of the armies, ever present and efficient to meet all the natural wants of the soldier, and to reduce his danger of sickness and mortality, as nearly as possible, to that of men of the same age at home.

AN ARAB WELCOME

IBecause thou com'st, a tired guest,Unto my tent, I bid thee rest.This cruse of oil, this skin of wine,These tamarinds and dates, are thine:And while thou eatest, Hassan, there,Shall bathe the heated nostrils of thy mare.IIAllah il Allah! Even soAn Arab chieftain treats a foe:Holds him as one without a fault,Who breaks his bread and tastes his salt;And, in fair battle, strikes him deadWith the same pleasure that he gives him bread!ELIZABETH SARA SHEPPARD

You ask from me some particulars of the valued life so recently closed. Miss Sheppard was my friend of many years; I was with her to the last hour of her existence; but this is not the time for other than a brief notice of her career, and I comply with your request by sending you a slight memorial, hardly full enough for publication.

Elizabeth Sara Sheppard, the authoress of "Charles Auchester," "Counterparts," etc., was born at Blackheath, in England. Her father was a clergyman of unusual scholastic attainments, and took high honors at St. John's College, Oxford. Mr. Sheppard, on the mother's side, could number Hebrew ancestors, and this was the pride of his second daughter, the subject of this notice. Her love for the whole Hebrew race amounted to a passion, which found its expression in the romance of "Charles Auchester."

Very early she displayed a most decided poetic predisposition,—writing, when but ten years old, with surprising facility on every possible subject. No metre had any difficulties for her, and no theme seemed dull to her vivid intelligence,—her fancy being roused to action in a moment, by the barest hint given either by Nature or Art. Her first drama was written at this early age; it was called "Boadicea," and was composed immediately after she had been shown a field at Islington where this queen is said to have pitched her tent. Any one who asked was welcome to "some verses by 'Little Lizzie,'" written in her peculiar and fairy-like hand, (for when very young, her writing was remarkable for its extreme smallness and finish.) given with childlike simplicity, and artless ignorance of the worth of what she bestowed with a kiss and a smile.

Her poems were composed at once, with scarcely a correction. Her earlier ones, for the most part, were written at the corner of a large table, covered with the usual heaps of "after-lessons," in a school-room, where some twenty enfranchised girls were putting away copybooks, French grammars, etc., and getting out play-boxes and fancy-work, with the common amount of chatter and noise. Contrasted with such young persons, this child looked a strange, unearthly creature,—her large, dark gray eye full of inspiration, and every movement of her frame and tone of her voice instinct with delicate energy.

At the same age she would extemporize for hours on the organ, after wreathing the candlesticks with garden-flowers which she had brought in her hand,—their scent, she would say, suggesting the wild, sweet fancies which her fingers seemed able to call forth on the shortest notice. Persons straying into the church, as they often did, attracted by the sound of music, would declare the performer to be an experienced masculine musician.

When but a year older, she was an excellent Latin scholar, and, to use her father's words, she might then have "gone in for honors at Oxford." French she spoke and wrote fluently, besides reading Goethe and Schiller with avidity, and translating as fast as she read,—Schiller having always the preference. At fourteen she began the study of Hebrew, of which language she was a worshipper, and could not at that early age even let Greek alone. Her wonderful power of seizing on the genius of a language, and becoming for the time a foreigner in spirit, was noticed by all her teachers; her ear was so delicate that no subtile inflection ever escaped her, nor any idiom.

And now she surprised her most intimate friend by the present of a prose story, sent to her, when absent, in chapters by the post. This was succeeded by many other tales, and finally by "Charles Auchester,"—which romance, as well as that of "Counterparts," was written in the few hours she could command after her teaching was over: for in her mother's school she taught music the greater part of every day,—both theoretically and practically,—and also Latin.

Her health, always delicate, suffered wofully from this constant strain, and caused her to experience the most painful exhaustion, which, however, she never permitted to be an excuse for shirking an occupation naturally distasteful to her,—and doubly so, that through all the din of practice her thousand fancies clamored like caged birds eager for liberty.

The moment her hour of leisure came, she would hide herself with her best loved work in the quietest corner she could find; sometimes it was a little room in-doors, sometimes the summer-house, sometimes under a large mulberry-tree; and thus "Charles Auchester" and "Counterparts" were written, the former without one correction,—sheet after sheet, flung from her hand in the ardor of composition, being picked up and read by the friend who was in all her literary secrets. At last this same friend, finding she had no thought of publication, in a moment of playful daring, persuaded her to send the manuscript to Benjamin Disraeli, and he introduced it to his publishers. I quote from his letter to the author, which may not be out of place here:—

"No greater book will ever be written upon music, and it will one day be recognized as the imaginative classic of that divine art."

"Counterparts" and other tales soon followed. And about the same date she presented, anonymously, a volume of stories to the young daughter of Mr. John Hullah, of "Part Music" celebrity. They were in manuscript printing, (if such a term may be used,) written by her own hand, and remarkable for their curious beauty. The heading of each story was picked out in black and gold. The stories are named "Adelaide's Dream," "Little Wonder, or, The Children's Fairy," "The Bird of Paradise," "Sprömkari," (from a Scandinavian legend,) "The First Concert," "The Concert in the Hollow Tree," "Uncle, or, Which is the Prettiest?" "Little Ernest," "The Nautilus Voyage." These stories are illustrated, and have a lovely dedication to the little lady for whom they were written.

The author had attended the "Upper Singing-Schools" for the sake of more musical experience. Yet she then sang at sight perfectly, with any number of voices. She has left three published songs, dedicated to the Marchioness of Hastings, and a large number of manuscript poems.

Her character was in perfect keeping with the high tone of her books. Noble, generous, and self-forgetting, tender and most faithful in friendship, burning with indignation at injustice shown to another, longing to find virtues instead of digging for faults,—her greatest suffering arose from pained surprise, when persons proved themselves less noble than she had deemed them.

Her rich imagination and slender purse were open to all beggars, but for herself she asked nothing, and was constantly a willing sufferer from her own inability to toady a patron or to make a good bargain with a publisher.

She felt most warmly for her friends in America, whose comprehension of her views, and honest, open appreciation of her books, inspired her with an ardent desire to write for them a romance in her very best manner. She had sketched two, and, doubtful which to proceed with first, contemplated sending both to an American friend for his decision; but constant suffering stayed her hand.

In the early spring she grew weaker day by day, and died on the 13th of March, at Brixton, in England, at the age of thirty-two.

Those who loved either her person or her works will find her place forever empty.

Among her manuscript papers I found this sketch, which has a peculiar significance now that the writer has passed away. It has never been printed.

A NICHE IN THE HEART

I had been wandering, almost all day, in the cathedral of a town at some distance from London. I had sketched its carved pulpit, one or two cherub faces looking down from its columns, some of its best reliefs, and its oldest monument. It was evening, and I could no longer see to draw, though pencillings of light still fell on the pavement through the larger windows, whose colors were softened like those of the lunar rainbow; and still the edges of the stalls were gilded with the last gleams of sunset, though the seats were filled already with those phantoms which twilight seems to create in such a place. The monuments looked calmer and less formal than when daylight bared all their defects of design or finish; they seemed now worthy of their position beneath the vaulted roof, and even, adjuncts themselves to the harmony of the architecture. One among them, noticeable in the daytime for its refined workmanship, now gleamed out fresher and whiter than the rest, as was natural, for it had been placed there but a little while; but it had besides more expression, in its very simplicity, than such-like mementos of stone or marble usually contain. This was the memento of a husband's regret, and, as such, touching, however vain: a delicate form drooping on a bier, at whose head stood an angel, with an infant in his arms, which he raised to heaven with an air of triumph; while at the foot of the death-bed a figure knelt, in all the relaxed abandonment of woe. Marvellously, and out of small means, the chisel had conveyed this impression; for the kneeling figure was mantled from head to foot, and had its face hidden in the folds of the drapery which skirted the bier,—veiled, like the face of the tortured father in the old tragic tale.

While I gazed, I insensibly approached the still group; and while musing what manner of grief it might be, which could solace by perpetuating its mere image, I observed two other persons, whose entrance I had not been aware of, but whose attention was evidently directed to what had attracted mine. They were a lady and a gentleman, and the latter seemed actually supporting the former, who leaned heavily upon his arm, as it appeared from her manner of carriage, so weakly and wearily she stood. Her form was extremely slight, and the outline of her countenance sharp from attenuation, and in that uncertain light, or rather shade, she looked almost as pale as the carved faces before us. The gentleman, who was of a stately height, bent over her with an anxious air, while she gazed fixedly upon the monument. Her silence seemed to oppress him, for after a minute or two he asked her whether it was not very beautiful. "You know," she answered, in one of those low voices that are more impressive than the loudest, "You know I always suspect those memorials. I would rather have a niche in the heart."

They passed on, and left me standing there. I know not whether the fragile speaker has earned the monument she desired, whether those feeble footsteps have found their repose,—"a quiet conscience in a quiet breast,"—but her words struck me, and I have often thought of them since.

There is always something which seems less than the intention in a monument to heroism or to goodness, the patriot of the country, or the missionary of civilization. Every one feels that the graves of War, the many in the one, where link is welded to link in the chain of glory, are more sublime, more sacred, than the exceptional mausoleum. Every one has been struck with repugnant melancholy in the city church-yard, where tomb presses against tomb, and multitude in death destroys identity, saving where the little greatness of wealth or rank may provide itself a separate railing or an overtopping urn. Even in the more suggestive solitude of the country, one cannot but contrast the few hillocks here and there carefully weeded, and their trained and tended rose-bushes, with the many more neglected and sunken, whose distained stones the brier-tangle half conceals, and whose forget-me-nots have long since died for want of water. One may even muse unprofitably (despite the moralist) in our picturesque cemeteries, and as unprofitably in those abroad, with their crowds of crosses and monotony of immortal wreaths. In fact, whether on grounds philosophical or religious, it is not good to brood on mortality for itself alone; better rather to recall the living past, and in the living present prepare for the perfect future.