полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 269, August 18, 1827

Novels are productions more easily criticised than any others: every one may judge for himself of the truth or probability of the events, and the accuracy of the features of character. It is impossible almost to deceive a reader—to palm upon him fiction for truth; for the truth is felt, if it be there, and the falsehood is palpable and revolting. There is also an extensive light of information in them. They do not merely give one scene, or character, or class of characters; but their principles are generally applicable to a very wide extent—they exercise the mind to a habit of observation, and so far from giving false views of life, they more frequently direct us to its true estimate. To be sure, there is sometimes a degree of improbability in some of the incidents, which is mostly forgiven, if the whole mass be, in the main, true and accurate. There are certain standard incidents, which are common property—such as the discovery of relationships—the change of children—and liberal aunts, who make nothing of presenting a young married couple with twenty or thirty thousand pounds on their wedding day; but, if any young lady or gentleman is silly enough to marry, without the means of support, because they have read such things in novels, and have also read of rich uncles all of a sudden returning from the East or West Indies, to shower gold and pearls on all their relations, all that must be said for them is, that they have not sufficient sense to read "Aesop's Fables," and they might as easily be misled into the imagination that brutes could talk. It is a very weak charge against novels, that they present false views of life; for, when they do, none but silly people read them; and they are just as wise after, as they were before.

If there be any evil in novels at all, it is when they take people from their business—when they occupy a mother's time to the neglect of her children—when they lead idle boys to neglect their lessons, and when they lead idle gentlefolks to fancy themselves employed, when they are only killing time. W.P.S.

CARRIER PIGEONS(For the Mirror.)It appears by the Dutch papers that pigeons are now used to forward correspondence between different countries in Europe, and one was lately found resting on a house in Rotterdam. The carrier pigeon has its name from its remarkable sagacity in returning to the place where it was bred; and Lightow assures us, that one of these birds would carry a letter from Babylon to Aleppo, which is thirty days' journey, in forty-eight hours. This pigeon was employed in former times by the English factory to convey intelligence from Scanderoon of the arrival of company's ships in that port, the name of the ship, the hour of her arrival, and whatever else could be comprised in a small compass, being written on a slip of paper, which was secured in such a manner under the pigeon's wing as not to impede its flight; and her feet were bathed in vinegar, with a view to keep them cool, and prevent her being tempted by the sight of water to alight, by which the journey might have been prolonged, or the billet lost. The pigeons performed this journey in two hours and a half. The messenger had a young brood at Aleppo, and was sent down in an uncovered cage to Scanderoon, from whence, as soon as set at liberty, she returned with all possible expedition to her nest. It is said that the pigeons when let fly from Scanderoon, instead of bending their course towards the high mountains surrounding the plain, mounted at once directly up, soaring still almost perpendicularly till out of sight, as if to surmount at once the obstacles intercepting their view of the place of their destination. Maillet, in his "Description de l'Egypt," tells us of a pigeon despatched from Aleppo to Scanderoon, which, mistaking its way, was absent for three days, and in that time had made an excursion to the island of Ceylon; a circumstance then deduced from finding green cloves in the bird's stomach, and credited at Aleppo. In the time of the holy wars, certain Saracen ambassadors who came to Godfrey of Antioch from a neighbouring prince, sent intelligence to their master of the success of their embassy, by means of pigeons, fixing the billet to the bird's tail. Hirtius and Brutus, at the siege of Modena, held a correspondence with one another by means of pigeons. Ovid informs us that Taurosthenus, by a pigeon stained with purple, gave notice to his father of his victory at the Olympic games, sending it to him at Ægina; and Anacreon tells us, that he conveyed a billet-doux to his beautiful Bathyllid, by a dove. Thus, says Bewick, "the bird is let loose, and in spite of surrounding armies and every obstacle that would have effectually prevented any other means of conveyance, guided by instinct alone, it returns directly home, where the intelligence is so much wanted. Sometimes they have been the peaceful bearers of glad tidings to the anxious lover, and to the merchant of the no less welcome news of the safe arrival of his vessel at the desired port."

In this flighty and pigeoning age, I would recommend a pigeon-carrier-company, whose shares might be elevated to any height.

P. T. W.

MISCELLANIES

NAMES OF SHEEPA ram or wether lamb, after being weaned, is called a hog, or hoggitt, tag, or pug, throughout the first year, or until it renew two teeth; the ewe, a ewe-lamb, ewe-tag, or pug. In the second year the wether takes the name of shear-hog, and has his first two renewed or broad teeth, or he is called a two-toothed tag or pug; the ewe is called a thaive, or two-toothed ewe tag, or pug. In the third year, a shear hog or four-toothed wether, a four-toothed ewe or thaive. The fourth year, a six-toothed wether or ewe. The fifth year, having eight broad teeth, they are said to be full-mouthed sheep. Their age also, particularly of the rams, is reckoned by the number of times they have been shorn, the first shearing taking place in the second year; a shearing, or one-shear, two-shear, &c. The term pug is, I believe, nearly become obsolete. In the north and in Scotland, ewe hogs are called dimonts, and in the west of England ram lambs are called pur lambs.

The ancient term tup, for a ram, is in full use. Crone still signifies an old ewe. Of crock, I know nothing of the etymology, and little more of the signification, only that the London butchers of the old school, and some few of the present, call Wiltshire sheep horned crocks. I believe crock mutton is a term of inferiority.

Conceit and confidence are both of them cheats; the first always imposes on itself, the second frequently deceives others too.—Zimmerman.

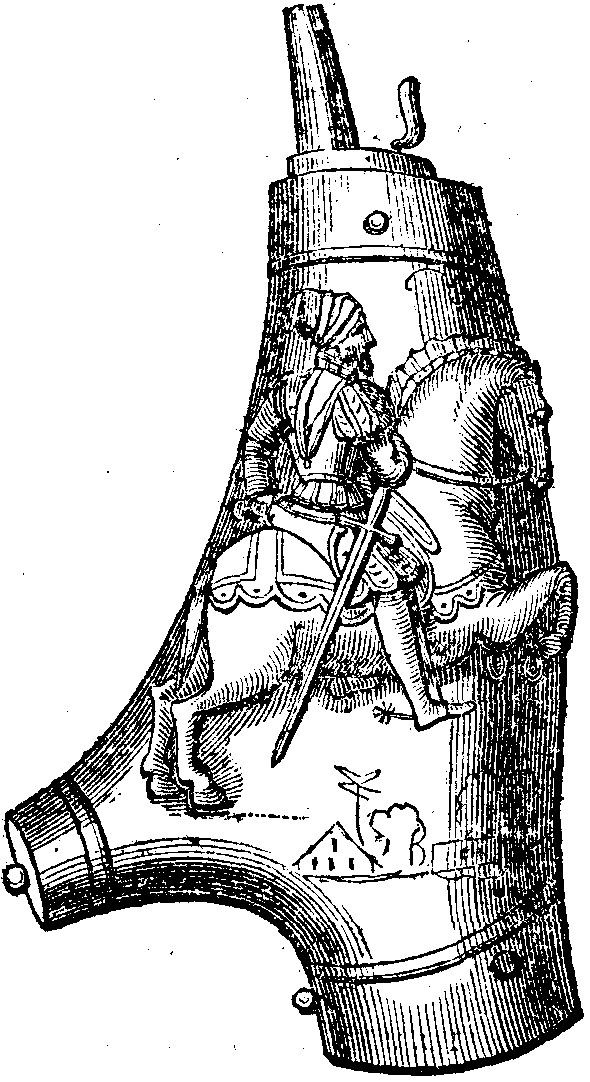

ANCIENT POWDER FLASK

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

SIR,—The enclosed curious drawing of an ancient powder "flaske," both in form and ornament, may not be uninteresting to the readers of your valuable MIRROR at the approaching sporting season.

Gunpowder, when first invented, was carried in the horns of animals, for safety and convenience; though some time afterwards placed in flat leather cases or bottles, invented by the Germans, and called "flaskes." A remarkably curious one of this description, evidently of the time of Queen Elizabeth, is here represented, and is formed of ivory, somewhat in the shape of a stag's horn; the ornaments on it are carved in a good bold style, and represent an armed figure on horseback in full chase. The "flaske" is tipped at the end with silver, and measures about eight inches in length.

I remain, yours,

* *

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

CHARACTER OF THE SEPOYSOur countrymen at home are frequently perplexed by the apparent contradictions of a traveller from the East, when describing the characters and manners of the inhabitants of Hindostan. If, for instance, he alludes to our gallant sepoys, he pours forth unmeasured praise, and appears altogether charmed with their docility, courage, honour, and fidelity. On the other hand, his opinion of the natives in the aggregate is often as exactly the reverse as it is possible to imagine. They are described, perhaps, in the strongest terms, as at once servile, cowardly, treacherous, and ungrateful. The fact is, that our troops are all from the northern provinces of India, the natives of which are a brave and generous race, who hold the profession of arms in the highest estimation. The Bengallees on the contrary, (with the most universal and shameless indifference to truth,) are mean, effeminate, and avaricious. They are chiefly composed of merchants, copying clerks, mechanics, and domestic servants, and are invariably refused admittance into the company's army. These people are vastly inferior to the natives of the upper provinces in mental and corporeal energy, though more polished in their manners, and more easily initiated into the arts and mysteries of civilized life. I will illustrate the nice sense of honour which distinguishes the native soldier by the following anecdote.

A sepoy of the Bengal native infantry was accused by one of his comrades of having stolen a rupee and a pair of trousers. The sergeant-major before whom, in the first instance, the charge was brought, was both unable and unwilling to give it credence. Besides the unusual circumstance of a native soldier being guilty of so base an act, the accused sepoy had always been remarkably conspicuous for his brave and upright conduct. His breast was literally covered with medals, and he had long been accustomed to the voice of praise. Still, however, justice demanded that the charge should not be dismissed without an impartial investigation. The whole affair was brought to the notice of the commanding officer, who desired that the sepoy's residence should be immediately and thoroughly examined. On opening his knapsack, to the utter astonishment and regret of the whole regiment, the stolen property was discovered. None, however, looked more thunderstruck than the sepoy himself. He clenched his teeth in bitter agony, but spoke not a single word. The colonel told him, that though circumstances were fearfully against him, he would not yet pronounce him guilty, as it was not impossible he might be the victim of some malignant design. He therefore dismissed him from his presence until the result of further inquiries should produce a full conviction of his guilt or innocence. In a few hours the sepoy was observed to leave his little hut, and walk with hurried steps to a neighbouring field. He was soon concealed from sight by a thick cluster of bamboos, beneath which he had often sheltered himself from the noontide sun. Suspecting the purpose of his present visit to so retired a spot, a comrade followed him, but was unfortunately too late to arrest the hand of the determined suicide. The poor fellow lay stretched on the ground, with his head hanging back, and the blood gushing from his open throat. He had effected his purpose with a sharp knife, which he still grasped, as if with the intention of inflicting another wound. He was carried to the hospital, and carefully attended, but the surgeon immediately pronounced his recovery impossible. A pen and ink were brought to him, and he wrote with some difficulty on a slip of paper, that he firmly hoped he had not failed in his attempt to destroy himself, for life was of no value without honour. He stated, too, that though it might now be almost useless to affirm his innocence, he hoped that a time might come when his memory should be freed from its present stain. He lingered no less than fifteen days in this dreadful state, and died, at last, apparently of mere starvation. It was my painful duty, as "officer of the day," to visit the hospital very frequently, and he invariably made signs of a desire for food. This it was, of course, impossible to give him, and any nourishment would merely have prolonged his misery. Two days before he died, it was discovered that a Bengallee servant of low caste, who had taken offence on some trivial occasion, had placed the stolen goods in the sepoy's bundle, and then urged the owner to accuse him of the theft. The disclosure of this circumstance appeared to give infinite satisfaction to the dying soldier.

London Weekly Review.

HOUSE LAUNCHINGThe launching of the two brick houses in Garden-street was completely successful. They were moved nearly ten feet, occupied at the time by their tenants, without having sustained any injury. The preparations were the work of some time; the two buildings having been put upon ways, or into a cradle, were easily screwed on a new foundation. The inventor of this simple and cheap mode of moving tenanted brick buildings, is entitled to the thanks of the public. In the course of time, it is likely that houses will be put up upon ways at brick or stone quarries, and sold as ships are, to be delivered in any part of the city.—American Paper.

In the course of time we really do not know what is not to happen in America. Jonathan promises to grow so big, and to do such wonders in a day or two, that no bounds can be placed to his performances in the future tense. Everything will of course be on a scale of grandeur proportioned to his country, which, as he observes in his Travels in England, is "bigger and more like a world" than our boasted land; instead, therefore, of going about in confined, close carriages as people do here, the Americans will rattle through the streets to their routs and parties in their houses. One tenanted brick building will be driven up to the door of another. A further improvement may here be suggested. Jonathan is fond of chairs with rockers, that is, chairs with a cradle-bottom, on which he see-saws himself as he smokes his pipe and fuddles his sublime faculties with liquor. Now by putting a house on rockers, this trouble and exertion of the individual on a scale so small and unworthy of a great people would be spared, and every tenant of a brick building would be rocked at the same time, and by one common piece of machinery. The effect of a whole city nid-nid-nodding after dinner, will be extremely magnificent and worthy of America. As for the feasibility of the thing, nothing can be more obvious. If houses can be put upon cradles for launching, they can be put upon cradles for rocking; and if tenants do not object to being conveyed from one part of the city to another in their mansions, they will not surely take fright at an agreeable stationary see-saw in them.—London Magazine.

GOOD NIGHT TO THE SEASONThus runs the world away.—HAMLET.

Good-night to the Season! 'tis over!Gay dwellings no longer are gay;The courtier, the gambler, the lover,Are scatter'd, like swallows, away:There's nobody left to invite one,Except my good uncle and spouse;My mistress is bathing at Brighton,My patron is sailing at Cowes:For want of a better employment,Till Ponto and Don can get out,I'll cultivate rural enjoyment,And angle immensely for trout.Good-night to the Season!—the buildingsEnough to make Inigo sick;The paintings, and plasterings, and gildings,Of stucco, and marble, and brick;The orders deliciously blended,From love of effect, into one;The club-houses only intended,The palaces only begun;The hell where the fiend, in his glory,Sits staring at putty and stones,And scrambles from story to story,To rattle at midnight his bones.Good-night to the Season!—the dances,The fillings of hot little rooms,The glancings of rapturous glances,The fancyings of fancy costumes;The pleasures which Fashion makes duties,The praisings of fiddles and flutes,The luxury of looking at beauties,The tedium of talking to mutes;The female diplomatists, plannersOf matches for Laura and Jane,The ice of her Ladyship's manners,The ice of his Lordship's champagne.Good-night to the Season!—the ragesLed off by the chiefs of the throng,The Lady Matilda's new pages,The Lady Eliza's new song;Miss Fennel's Macaw, which at Boodle'sIs held to have something to say;Mrs. Splenetic's musical Poodles,Which bark "Batti, batti!" all day:The pony Sir Araby sported,As hot and as black as a coal,And the Lion his mother imported,In bearskins and grease, from the Pole.Good-night to the Season!—the Toso,So very majestic and tall;Miss Ayton, whose singing was so so,And Pasta, divinest of all;The labour in vain of the Ballet,So sadly deficient in stars;The foreigners thronging the Alley,Exhaling the breath of cigars;The "loge," where some heiress, how killing,Environ'd with Exquisites sits,The lovely one out of her drilling,The silly ones out of their wits.Good-night to the Season!—the splendourThat beam'd in the Spanish Bazaar,Where I purchased—my heart was so tender—A card-case,—a pasteboard guitar,—A bottle of perfume,—a girdle,—A lithograph'd Riego full-grown,Whom Bigotry drew on a hurdle,That artists might draw him on stone,—A small panorama of Seville,—A trap for demolishing flies,—A caricature of the Devil,And a look from Miss Sheridan's eyes.Good-night to the Season!—the flowersOf the grand horticultural fête,When boudoirs were quitted for bowers,And the fashion was not to be late;When all who had money and leisure,Grow rural o'er ices and wines,All pleasantly toiling for pleasure,All hungrily pining for pines,And making of beautiful speeches,And marring of beautiful shows,And feeding on delicate peaches,And treading on delicate toes.Good night to the Season!—anotherWill come with its trifles and toys,And hurry away, like its brother,In sunshine, and odour, and noise.Will it come with a rose or a briar?Will it come with a blessing or curse?Will its bonnets be lower or higher?Will its morals be better or worse?Will it find me grown thinner or fatter,Or fonder of wrong or of right.Or married, or buried?—no matter,Good-night to the season, Good-night!New Monthly Magazine.

TIGER TAMINGA party of gentlemen from Bombay, one day visiting the stupendous cavern temple of Elephanta, discovered a tiger's whelp in one of the obscure recesses of the edifice. Desirous of kidnapping the cub, without encountering the fury of its dam, they took it up hastily and cautiously, and retreated. Being left entirely at liberty, and extremely well fed, the tiger grew rapidly, appeared tame and fondling as a dog, and in every respect entirely domesticated. At length, when it had attained a vast size, and notwithstanding its apparent gentleness, began to inspire terror by its tremendous powers of doing mischief, a piece of raw meat, dripping with blood, fell in its way. It is to be observed, that, up to that moment, it had been studiously kept from raw animal food. The instant, however, it had dipped its tongue in blood, something like madness seemed to have seized upon the animal; a destructive principle, hitherto dormant, was awakened—it darted fiercely, and with glaring eyes, upon its prey—tore it with fury to pieces—and, growling and roaring in the most fearful manner, rushed off towards the jungles.—London Weekly Review.

RUNNING A MUCKThe inhabitants of the Indian Archipelago, and particularly of the island of Java, are of a very sullen and revengeful disposition. When they consider themselves grossly insulted, they are observed to become suddenly thoughtful; they squat down upon the ground, and appear absorbed in meditation. While in this position, they revolve in their breasts the most bloody and ferocious projects of revenge, and, by a desperate effort, reconcile themselves with death. When their terrible resolution is taken, their eyes appear to flash fire, their countenance assumes an expression of preternatural fury; and springing suddenly on their feet, they unsheath their daggers, plunge them into the heart of every one within their reach, and rushing out into the streets, deal wounds and murder as they run, until the arrow or dagger of some bold individual terminates their career. This is called running a muck.—Ibid.

THE SELECTOR, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

THE JEW'S HARPThe memoirs of Madame de Genlis first made known the astonishing powers of a poor German soldier on the Jew's harp. This musician was in the service of Frederick the Great, and finding himself one night on duty under the windows of the King, playing the Jew's harp with so much skill, that Frederick, who was a great amateur of music, thought he heard a distinct orchestra. Surprised on learning that such an effect could be produced by a single man with two Jew's harps, he ordered him into his presence; the soldier refused, alleging, that he could only be relieved by his colonel; and that if he obeyed, the king would punish him the next day, for having failed to do his duty. Being presented the following morning to Frederick, he was heard with admiration, and received his discharge and fifty dollars. This artist, whose name Madame de Genlis does not mention, is called Koch; he has not any knowledge of music, but owes his success entirely to a natural taste. He has made his fortune by travelling about, and performing in public and private, and is now living retired at Vienna, at the advanced age of more than eighty years. He used two Jew's harps at once, in the same manner as the peasants of the Tyrol, and produced, without doubt, the harmony of two notes struck at the same moment, which was considered by the musically-curious as somewhat extraordinary, when the limited powers of the instrument were remembered. It was Koch's custom to require that all the lights should be extinguished, in order that the illusion produced by his playing might be increased.

It was reserved, however, for Mr. Eulenstein to acquire a musical reputation from the Jew's harp. After ten years of close application and study, this young artist has attained a perfect mastery over this untractable instrument. In giving some account of the Jew's harp, considered as a medium for musical sounds, we shall only present the result of his discoveries. This little instrument, taken singly, gives whatever grave sound you may wish to produce, as a third, a fifth, or an octave. If the grave tonic is not heard in the bass Jew's harp, it must be attributed, not to the defectiveness of the instrument, but to the player. In examining this result, you cannot help remarking the order and unity established by nature in harmonical bodies, which places music in the rank of exact sciences. The Jew's harp has three different tones; the bass tones of the first octave bear some resemblance to those of the flute and clarionet; those of the middle and high, to the vox humana of some organs; lastly, the harmonical sounds are exactly like those of the harmonica. It is conceived, that this diversity of tones affords already a great variety in the execution, which is always looked upon as being feeble and trifling, on account of the smallness of the instrument. It was not thought possible to derive much pleasure from any attempt which could be made to conquer the difficulties of so limited an instrument; because, in the extent of these octaves, there were a number of spaces which could not be filled up by the talent of the player; besides, the most simple modulation became impossible. Mr. Eulenstein has remedied that inconvenience, by joining sixteen Jew's harps, which he tunes by placing smaller or greater quantities of sealing-wax at the extremity of the tongue. Each harp then sounds one of the notes of the gamut, diatonic or chromatic, and the performer can fill all the intervals, and pass all the tones, by changing the harp. That these mutations may not interrupt the measure, one harp must always be kept in advance, in the same manner as a good reader advances the eye, not upon the word which he pronounces, but upon that which follows.—Philosophy in Sport.

FORM OF ANCIENT BOOKS, THEIR ILLUMINATIONS, &cThe mode of compacting the sheets of their books remained the same among the Greeks during a long course of time. The sheets were folded three or four together, and separately stitched: these parcels were then connected nearly in the same mode as is at present practised. Books were covered with linen, silk, or leather.

The page was sometimes undivided; sometimes it contained two, and in a few instances of very ancient MSS., three columns. A peculiarity which attracts the eye in many Greek manuscripts, consists in the occurrence of capitals on the margin, some way in advance of the line to which they belong; and this capital sometimes happens to be the middle letter of a word. For when a sentence finishes in the middle of a line, the initial of the next is not distinguished, that honour being conferred upon the incipient letter of the next line; thus—