полная версия

полная версияThe Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

Ib. c. 10. p. 279.

Derwent! should this page chance to fall under your eye, for my sake read, fag, subdue, and take up into your proper mind this chapter 10 of Free Will.

Ib. p. 281.

Of these five kinds of liberty, the two first agree only to God, so that in the highest degree

I add, except as in God, and God in us. Now the latter alone is will; for it alone is ens super ens. And here lies the mystery, which I dare not openly and promiscuously reveal.

Ib.

Yet doth not God's working upon the will take from it the power of dissenting, and doing the contrary; but so inclineth it, that having liberty to do otherwise, yet she will actually determine so.

This will not do. Were it true, then my understanding would be free in a mathematical proportion; or the whole position amounts only to this, that the will, though compelled, is still the will. Be it so; yet not a free will. In short, Luther and Calvin are right so far. A creaturely will cannot be free; but the will in a rational creature may cease to be creaturely, and the creature,

Ib. p. 283.

It is not given, nor is it wanting, to all men to have an insight into the mystery of the human will and its mode of inherence on the will which is God, as the ineffable causa sui; but this chapter will suffice to convince you that the doctrines of Calvin were those of Luther in this point; – that they are intensely metaphysical, and that they are diverse toto genere from the merely moral and psychological – tenets of the modern Calvinists. Calvin would have exclaimed, 'fire and fagots!' before he had gotten through a hundred pages of Dr. Williams's Modern Calvinism.

Ib. c. 11. p. 296.

Neither can Vega avoid the evidence of the testimonies of the Fathers, and the decree of the Council of Trent, so that he must be forced to confess that no man can so collectively fulfil the law as not to sin, and consequently, that no man can perform that the law requireth.

The paralogism of Vega as to this perplexing question seems to lurk in the position that God gives a law which it is impossible we should obey collectively. But the truth is, that the law which God gave, and which from the essential holiness of his nature it is impossible he should not have given, man deprived himself of the ability to obey. And was the law of God therefore to be annulled? Must the sun cease to shine because the earth has become a morass, so that even that very glory of the sun hath become a new cause of its steaming up clouds and vapors that strangle the rays? God forbid! But for the law I had not sinned. But had I not been sinful the law would not have occasioned me to sin, but would have clothed me with righteousness, by the transmission of its splendour. Let God be just, and every man a liar.

B. iv. c. 4. p. 346.

The Church of God is named the 'Pillar of Truth;' not as if truth did depend on the Church, &c.

Field might have strengthened his argument, by mention of the custom of not only affixing records and testimonials to the pillars, but books, &c.

Ib. c. 7. p. 353.

Others therefore, to avoid this absurdity, run into that other before mentioned, that we believe the things that are divine by the mere and absolute command of our will, not finding any sufficient motives and reasons of persuasion.

Field, nor Count Mirandula have penetrated to the heart of this most fundamental question. In all proper faith the will is the prime agent, but not therefore the choice. You may call it reason if you will, but then carefully distinguish the speculative from the practical reason, and the reason itself from the understanding.

Ib. c. 8. p. 356.

Illius virtute (saith he) illuminati, jam non aut nostro, aut aliorum judicio credimus a Deo esse Scripturam, sed supra humanum judicium certo certius constituimus, non secus ac si ipsius Dei numen illic intueremur, hominum ministerio ab ipsissimo Dei ore fluxisse.

Greatly doth this fine passage need explanation, that knowing what it doth mean, the reader may understand what it doth not mean, nor of necessity imply. Without this insight, our faith may be terribly shaken by difficulties and objections. For example; If all the Scripture, then each component part; thence every faithful Christian infallible, and so on.

Ib. p. 357.

In the second the light of divine reason causeth approbation of that they believe: in the third sort, the purity of divine understanding apprehendeth most certainly the things believed, and causeth a foretasting of those things that hereafter more fully shall be enjoyed.

Here too Field distinguishes the understanding from the reason, as experience following perception of sense. But as perception through the mere presence of the object perceived, whether to the outward or inner sense, is not insight which belongs to the 'light of reason,' therefore Field marks it by 'purity' that is unmixed with fleshly sensations or the idola of the bodily eye. Though Field is by no means consistent in his epitheta of the understanding, he seldom confounds the word itself. In theological Latin, the understanding, as influenced and combined with the affections and desires, is most frequently expressed by cor, the heart. Doubtless the most convenient form of appropriating the terms would be to consider the understanding as man's intelligential faculty, whatever be its object, the sensible or the intelligible world; while reason is the tri-unity, as it were, of the spiritual eye, light, and object.

Ib. c. 10. p. 358.

Of the Papists preferring the Church's authority before the Scripture.

Field, from the nature and special purpose of his controversy, is reluctant to admit any error in the Fathers, – too much so indeed; and this is an instance. We all know what we mean by the Scriptures, but how know we what they mean by the Church, which is neither thing nor person? But this is a very difficult subject.

Ib. p. 359.

First, so as if the Church might define contrary to the Scriptures, as she may contrary to the writings of particular men, how great soever.

Verbally, the more sober divines of the Church of Rome do not assert this; but practically and by consequence they do. For if the Church assign a sense contradictory to the true sense of the Scripture, none dare gainsay it.28

Ib.

This we deny, and will in due place improve their error herein.

That is, prove against, detect, or confute.

Ib. c. 11. p. 360.

If the comparison be made between the Church consisting of all the believers that are and have been since Christ appeared in the flesh, so including the Apostles, and their blessed assistants the Evangelists, we deny not but that the Church is of greater authority, antiquity, and excellency than the Scriptures of the New Testament, as the witness is better than his testimony, and the law-giver greater than the laws made by him, as Stapleton allegeth.

The Scriptures may be and are an intelligible and real one, but the Church on earth can in no sense be such in and through itself, that is, its component parts, but only by their common adherence to the body of truth made present in the Scripture. Surely you would not distinguish the Scripture from its contents?

Ib. c. 12. p. 361.

For the better understanding whereof we must observe, as Occam fitly noteth, that an article of faith is sometimes strictly taken only for one of those divine verities, which are contained in the Creed of the Apostles: sometimes generally for any catholic verity.

I am persuaded, that this division will not bear to be expanded into all its legitimate consequences sine periculo vel fidei vel charitatis. I should substitute the following:

1. The essentials of that saving faith, which having its root and its proper and primary seat in the moral will, that is, in the heart and affections, is necessary for each and every individual member of the church of Christ:

2. Those truths which are essential and necessary in order to the logical and rational possibility of the former, and the belief and assertion of which are indispensable to the Church at large, as those truths without which the body of believers, the Christian world, could not have been and cannot be continued, though it be possible that in this body this or that individual may be saved without the conscious knowledge of, or an explicit belief in, them.

Ib.

And therefore before and without such determination, men seeing clearly the deduction of things of this nature from the former, and refusing to believe them, are condemned of heretical pertinacy.

Rather, I should think, of a nondescript lunacy than of heretical pravity. A child may explicitly know that 5 + 5 = 10, yet not see that therefore 10 – 5 = 5; but when he has seen it how he can refrain from believing the latter as much as the former, I have no conception.

Ib. c. 16. p. 367.

And the third of jurisdiction; and so they that have supreme power, that is, the Bishops assembled in a general Council, may interpret the Scriptures, and by their authority suppress all them that shall gainsay such interpretations, and subject every man that shall disobey such determinations as they consent upon, to excommunication and censures of like nature.

This would be satisfactory, if only Field had cleared the point of the communion in the Lord's Supper; whether taken spiritually, though in consequence of excommunication not ritually, it yet sufficeth to salvation. If so, excommunication is merely declarative, and the evil follows not the declaration but that which is truly declared, as when Richard says that Francis deserves the gallows, as a robber. The gallows depends on the fact of the robbery, not on Richard's saying.

Ib. c. 29. p. 391.

In the 1 Cor. 15. the Greek, that now is, hath in all copies; the first man was of the earth, earthly; the second man is the Lord from heaven. The latter part of this sentence Tertullian supposeth to have been corrupted, and altered by the Marcionites. Instead of that the Latin text hath; the second man was from heaven, heavenly, as Ambrose, Hierome, and many of the Fathers read also.

There ought to be, and with any man of taste there can be, no doubt that our version is the true one. That of Ambrose and Jerome is worthy of mere rhetoricians; a flat formal play of antithesis instead of the weight and solemnity of the other.29 According to the former the scales are even, in the latter the scale of Christ drops down at once, and the other flies to the beam like a feather weighed against a mass of gold.

Append. Part. I. s. 4. p. 752.

And again he saith, that every soul, immediately upon the departure hence, is in this appointed invisible place, having there either pain, or ease and refreshing; that there the rich man is in pain, and the poor in a comfortable estate. For, saith he, why should we not think, that the souls are tormented, or refreshed in this invisible place, appointed for them in expectation of the future judgment?

This may be adduced as an instance, specially, of the evil consequences of introducing the idolon of time as an ens reale into spiritual doctrines, thus understanding literally what St. Paul had expressed by figure and adaptation. Hence the doctrine of a middle state, and hence Purgatory with all its abominations; and an instance, generally, of the incalculable possible importance of speculative errors on the happiness and virtue of man-kind.

Notes on Donne 30

There have been many, and those illustrious, divines in our Church from Elizabeth to the present day, who, overvaluing the accident of antiquity, and arbitrarily determining the appropriation of the words 'ancient,' 'primitive,' and the like to a certain date, as for example, to all before the fourth, fifth, or sixth century, were resolute protesters against the corruptions and tyranny of the Romish hierarch, and yet lagged behind Luther and the Reformers of the first generation. Hence I have long seen the necessity or expedience of a threefold division of divines. There are many, whom God forbid that I should call Papistic, or, like Laud, Montague, Heylyn, and others, longing for a Pope at Lambeth, whom yet I dare not name Apostolic. Therefore I divide our theologians into,

1. Apostolic or Pauline:

2. Patristic:

3. Papal.

Even in Donne, and still more in Bishops Andrews and Hackett, there is a strong Patristic leaven. In Jeremy Taylor this taste for the Fathers and all the Saints and Schoolmen before the Reformation amounted to a dislike of the divines of the continental Protestant Churches, Lutheran or Calvinistic. But this must, in part at least, be attributed to Taylor's keen feelings as a Carlist, and a sufferer by the Puritan anti-prelatic party.

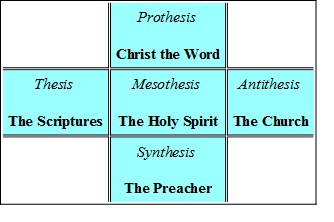

I would thus class the pentad of operative Christianity: —

The Papacy elevated the Church to the virtual exclusion or suppression of the Scriptures: the modern Church of England, since Chillingworth, has so raised up the Scriptures as to annul the Church; both alike have quenched the Holy Spirit, as the mesothesis of the two, and substituted an alien compound for the genuine Preacher, who should be the synthesis of the Scriptures and the Church, and the sensible voice of the Holy Spirit.

Serm. I. Coloss. i. 19, 20. p. 1.

Ib. E.

What could God pay for me? What could God suffer? God himself could not; and therefore God hath taken a body that could.

God forgive me, – or those who first set abroad this strange

Ib. p. 2. C.

And yet, even this dwelling fullness, even in this person Christ Jesus, by no title of merit in himself, but only quia complacuit, because it pleased the Father it should be so.

This, in the intention of the preacher, may have been sound, but was it safe, divinity? In order to the latter, methinks, a less equivocal word than 'person' ought to have been adopted; as 'the body and soul of the man Jesus, considered abstractedly from the divine Logos, who in it took up humanity into deity, and was Christ Jesus.' Dare we say that there was no self-subsistent, though we admit no self-originated, merit in the Christ? It seems plain to me, that in this and sundry other passages of St. Paul, the Father means the total triune Godhead.

It appears to me, that dividing the Church of England into two æras – the first from Ridley to Field, or from Edward VI to the commencement of the latter third of the reign of James I, and the second ending with Bull and Stillingfleet, we might characterize their comparative excellences thus: That the divines of the first æra had a deeper, more genial, and a more practical insight into the mystery of Redemption, in the relation of man toward both the act and the author, namely, in all the inchoative states, the regeneration and the operations of saving grace generally; – while those of the second æra possessed clearer and distincter views concerning the nature and necessity of Redemption, in the relation of God toward man, and concerning the connection of Redemption with the article of Tri-unity; and above all, that they surpassed their predecessors in a more safe and determinate scheme of the divine economy of the three persons in the one undivided Godhead. This indeed, was mainly owing to Bishop Bull's masterly work De Fide Nicæna,31 which in the next generation Waterland so admirably maintained, on the one hand, against the philosophy of the Arians, – the combat ending in the death and burial of Arianism, and its descent and metempsychosis into Socinianism, and thence again into modern Unitarianism, – and on the other extreme, against the oscillatory creed of Sherlock, now swinging to Tritheism in the recoil from Sabellianism, and again to Sabellianism in the recoil from Tritheism.

Ib.

First, we are to consider this fullness to have been in Christ, and then, from this fullness arose his merits; we can consider no merit in Christ himself before, whereby he should merit this fullness; for this fullness was in him before he merited any thing; and but for this fullness he had not so merited. Ille homo, ut in unitatem filii Dei assumeretur, unde meruit? How did that man (says St. Augustine, speaking of Christ, as of the son of man), how did that man merit to be united in one person with the eternal Son of God? Quid egit ante? Quid credidit? What had he done? Nay, what had he believed? Had he either faith or works before that union of both natures?

Dr. Donne and St. Augustine said this without offence; but I much question whether the same would be endured now. That it is, however, in the spirit of Paul and of the Gospel, I doubt not to affirm, and that this great truth is obscured by what in my judgment is the post-Apostolic Christopœdia, I am inclined to think.

Ib.

What canst thou imagine he could foresee in thee? a propensness, a disposition to goodness, when his grace should come? Either there is no such propensness, no such disposition in thee, or, if there be, even that propensness and disposition to the good use of grace, is grace; it is an effect of former grace, and his grace wrought before he saw any such propensness, any such disposition; grace was first, and his grace is his, it is none of thine.

One of many instances in dogmatic theology, in which the half of a divine truth has passed into a fearful error by being mistaken for the whole truth.

Ib. p. 6. D.

God's justice required blood, but that blood is not spilt, but poured from that head to our hearts, into the veins and wounds of our own souls: there was blood shed, but no blood lost.

It is affecting to observe how this great man's mind sways and oscillates between his reason, which demands in the word 'blood' a symbolic meaning, a spiritual interpretation, and the habitual awe for the letter; so that he himself seems uncertain whether he means the physical lymph, serum, and globules that trickled from the wounds of the nails and thorns down the sides and face of Jesus, or the blood of the Son of Man, which he who drinketh not cannot live. Yea, it is most affecting to see the struggles of so great a mind to preserve its inborn fealty to the reason under the servitude to an accepted article of belief, which was, alas! confounded with the high obligations of faith; – faith the co-adunation of the finite individual will with the universal reason, by the submission of the former to the latter. To reconcile redemption by the material blood of Jesus with the mind of the spirit, he seeks to spiritualize the material blood itself in all men! And a deep truth lies hidden even in this. Indeed the whole is a profound subject, the true solution of which may best, God's grace assisting, be sought for in the collation of Paul with John, and specially in St. Paul's assertion that we are baptized into the death of Christ, that we may be partakers of his resurrection and life32. It was not on the visible cross, it was not directing attention to the blood-drops on his temples and sides, that our blessed Redeemer said, This is my body, and this is my blood!

Ib. p. 9. A.

But if we consider those who are in heaven, and have been so from the first minute of their creation, angels, why have they, or how have they any reconciliation? &c.

The history and successive meanings of the term 'angels' in the Old and New Testaments, and the idea that shall reconcile all as so many several forms, and as it were perspectives, of one and the same truth – this is still a desideratum in Christian theology.

Ib. C.

For, at the general resurrection, (which is rooted in the resurrection of Christ, and so hath relation to him) the creature shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God; for which the whole creation groans, and travails in pain yet. (Rom. viii. 21.) This deliverance then from this bondage the whole creature hath by Christ, and that is their reconciliation. And then are we reconciled by the blood of his cross, when having crucified ourselves by a true repentance, we receive the real reconciliation in his blood in the sacrament. But the most proper and most literal sense of these words, is, that all things in heaven and earth be reconciled to God (that is, to his glory, to a fitter disposition to glorify him) by being reconciled to another in Christ; that in him, as head of the church, they in heaven, and we upon earth, be united together as one body in the communion of saints.

A very meagre and inadequate interpretation of this sublime text. The philosophy of life, which will be the corona et finis coronans of the sciences of comparative anatomy and zoology, will hereafter supply a fuller and nobler comment.

Ib. p. 9. A. and B.

The blood of the sacrifices was brought by the high priest in sanctum sanctorum, into the place of greatest holiness; but it was brought but once, in festo expiationis, in the feast of expiation; but in the other parts of the temple it was sprinkled every day. The blood of the cross of Christ Jesus hath had this effect in sancto sanctorum, &c. … (to) Christ Jesus.

A truly excellent and beautiful paragraph.

Ib. C.

If you will mingle a true religion, and a false religion, there is no reconciling of God and Belial in this text. For the adhering of persons born within the Church of Rome to the Church of Rome, our law says nothing to them if they come; but for reconciling to the Church of Rome, for persons born within the allegiance of the king, or for persuading of men to be so reconciled, our law hath called by an infamous and capital name of treason, and yet every tavern and ordinary is full of such traitors, &c.

A strange transition from the Gospel to the English statute-book! But I may observe, that if this statement could be truly made under James I, there was abundantly ampler ground for it in the following reign. And yet with what bitter spleen does Heylyn, Laud's creature, arraign the Parliamentarians for making the same complaint!