полная версия

полная версияThe Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

…

The argument from the mere universality of the belief, appears to me far stronger in favour of a surviving soul and a state after death, than for the existence of the Supreme Being. In the former, it is one doctrine in the Englishman and in the Hottentot; the differences are accidents not affecting the subject, otherwise than as different seals would affect the same wax, though Molly, the maid, used her thimble, and Lady Virtuosa an intaglio of the most exquisite workmanship.

Far otherwise in the latter. Mumbo Jumbo, or the cercocheronychous Nick-Senior, or whatever score or score thousand invisible huge men fear and fancy engender in the brain of ignorance to be hatched by the nightmare of defenceless and self-conscious weakness – these are not the same as, but are toto genere diverse from, the una et unica substantia of Spinosa, or the World-God of the Stoics.

And each of these again is as diverse from the living Lord God, the creator of heaven and earth. Nay, this equivoque on God is as mischievous as it is illogical: it is the sword and buckler of Deism.

Of the Existence and Nature of God

Besides, when we review our own immortal souls and their dependency upon some Almighty mind, we know that we neither did nor could produce ourselves, and withal know that all that power which lies within the compass of ourselves will serve for no other purpose than to apply several pre-existent things one to another, from whence all generations and mutations arise, which are nothing else but the events of different applications and complications of bodies that were existent before; and therefore that which produced that substantial life and mind by which we know ourselves, must be something much more mighty than we are, and can be no less indeed than omnipotent, and must also be the first architect and

A Rhodian leap! Where our knowledge of a cause is derived from our knowledge of the effect, which is falsely (I think) here supposed, nothing can be logically, that is, apodeictically, inferred, but the adequacy of the former to the latter. The mistake, common to Smith, with a hundred other writers, arises out of an equivocal use of the word 'know.' In the scientific sense, as implying insight, and which ought to be the sense of the word in this place, we might be more truly said to know the soul by God, than to know God by the soul.

…

So the Sibyl was noted by Heraclitus as

This fragment is misquoted and misunderstood: for –

– – – Not her's

To win the sense by words of rhetoric,

Lip-blossoms breathing perishable sweets;

But by the power of the informing Word

Roll sounding onward through a thousand years

Her deep prophetic bodements.

…

If the ascetic virtues, or disciplinary exercises, derived from the schools of philosophy (Pythagorean, Platonic and Stoic) were carried to an extreme in the middle ages, it is most certain that they are at present in a far more grievous disproportion underrated and neglected. The regula maxima of the ancient

Letter to a Godchild

To Adam Steinmetz K 83

My Dear GodchildI offer up the same fervent prayer for you now, as I did kneeling before the altar, when you were baptized into Christ, and solemnly received as a living member of His spiritual body, the Church.

Years must pass before you will be able to read with an understanding heart what I now write; but I trust that the all-gracious God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies, who, by his only begotten Son, (all mercies in one sovereign mercy!) has redeemed you from the evil ground, and willed you to be born out of darkness, but into light – out of death, but into life – out of sin, but into righteousness, even into the Lord our Righteousness; I trust that He will graciously hear the prayers of your dear parents, and be with you as the spirit of health and growth in body and mind.

My dear Godchild! – You received from Christ's minister at the baptismal font, as your Christian name, the name of a most dear friend of your father's, and who was to me even as a son, the late Adam Steinmetz, whose fervent aspiration and ever-paramount aim, even from early youth, was to be a Christian in thought, word, and deed – in will, mind, and affections.

I too, your Godfather, have known what the enjoyments and advantages of this life are, and what the more refined pleasures which learning and intellectual power can bestow; and with all the experience which more than threescore years can give, I now, on the eve of my departure, declare to you (and earnestly pray that you may hereafter live and act on the conviction) that health is a great blessing, – competence obtained by honorable industry a great blessing, – and a great blessing it is to have kind, faithful, and loving friends and relatives; but that the greatest of all blessings, as it is the most ennobling of all privileges, is to be indeed a Christian. But I have been likewise, through a large portion of my later life, a sufferer, sorely afflicted with bodily pains, languors, and bodily infirmities; and, for the last three or four years, have, with few and brief intervals, been confined to a sick-room, and at this moment, in great weakness and heaviness, write from a sick-bed, hopeless of a recovery, yet without prospect of a speedy recovery; and I, thus on the very brink of the grave, solemnly bear witness to you that the Almighty Redeemer, most gracious in His promises to them that truly seek Him, is faithful to perform what He hath promised, and has preserved, under all my pains and infirmities, the inward peace that passeth all understanding, with the supporting assurance of a reconciled God, who will not withdraw His Spirit from me in the conflict, and in His own time will deliver me from the Evil One!

O, my dear Godchild! eminently blessed are those who begin early to seek, fear, and love their God, trusting wholly in the righteousness and mediation of their Lord, Redeemer, Saviour, and everlasting High Priest, Jesus Christ!

O, preserve this as a legacy and bequest from your unseen Godfather and friend,

S. T. Coleridge.July 13, 183484.

END OF VOLUME THREE1

See Table Talk, p. 178, 2nd edit.

2

'Should it occur to any one that the doctrine blamed in the text, is but in accordance with that of the Church of England, in her rubric concerning spiritual communion, annexed to the Office for Communion of the Sick: he may consider, whether that rubric, explained (as if possible it must be) in consistency with the definition of a sacrament in the Catechism, can be meant for any but rare and extraordinary cases: cases as strong in regard of the Eucharist, as that of martyrdom, or the premature death of a well-disposed catechumen, in regard of Baptism.'

Keble's Pref. to Hooker, p. 85, n. 70. Ed.

3

According to Bishop Horne, the allusion is to the destruction of Pharaoh and his host in the Red Sea. – Ed.

4

See Horne in loc. note. – Ed.

5

The references are to Mr. Keble's edition (1836.) – Ed.

6

But see Mr. Keble's statement (Pref. xxix.), and the argument founded on discoveries and collation of MSS. since the note in the text was written. – Ed.

7

See Mr. Coleridge's work On the constitution of the Church and State according to the idea of each. – Ed.

8

See E. P. I. ii. 3. p. 252. – Ed.

9

See the Church and State, in which the ecclesia or Church in Christ, is distinguished from the enclesia, or national Church. – Ed.

10

See the essays generally from the fourth to the ninth, both inclusively, in Vol. III 3rd edition, more especially, the fifth essay. – Ed.

11

Part. I. c. i. vv. 151 – 6. – Ed.

12

See the essay on the idea of the Prometheus of Æschylus. Literary Remains, Vol. II p. 323. – Ed.

13

'Every man is born an Aristotelian, or a Platonist. I do not think it possible that any one born an Aristotelian can become a Platonist; and I am sure no born Platonist can ever change into an Aristotelian. They are the two classes of men, beside which it is next to impossible to conceive a third. The one considers reason a quality, or attribute; the other considers it a power. I believe that Aristotle never could get to understand what Plato meant by an idea. … Aristotle was, and still is, the sovereign lord of the understanding; the faculty judging by the senses. He was a conceptualist, and never could raise himself into that higher state, which was natural to Plato, and has been so to others, in which the understanding is distinctly contemplated, and, as it were, looked down upon, from the throne of actual ideas, or living, inborn, essential truths.'

Table Talk, 2d Edit. p. 95. – Ed.

14

See the Church and State, c. i. – Ed.

15

See post. – Ed.

16

But see the language of the Council of Trent:

Si quis dixerit justitiam acceptam non conservari atque etiam augeri coram. Deo per bona opera; sed opera ipsa fructus solummodo et signa esse justificationis adeptæ, non autem ipsius augendæ causam; anathema sit.

Sess. VI. Can. 24.

… Si quis dixerit hominis justificati bona opera ita esse dona Dei, ut non sint etiam bona ipsius justificati merita; aut ipsum justificatum bonis operibus, quæ ab eo per Dei gratiam, et Jesu Christi meritum, cujus vivum membrum est, fiunt, non vere mereri augmentum gratiæ, vitam æternam, et ipsius vitæ æternæ, si tamen in gratia decesserit, conscecutionem atque etiam gloriæ augmentum, anathema sit.

Ib. Can. 32. – Ed.

17

Rom. ii. 12. – Ed.

18

Matt. xix. 8. – Ed.

19

Folio 1628. – Ed.

20

The following letter was written on, and addressed with, the book to the Rev. Derwent Coleridge. – Ed.

21

P. L. III. 487. – Ed.

22

i. 27. See Aids to Reflection. 3d edit. p. 17. n. – Ed.

23

– – whence the soul

Reason receives, and reason is her being,

Discursive or intuitive.

P. L. v. 426. – Ed.

24

The reader of the Aids to Reflection will recognize in this note the rough original of the passages p. 313, &c. of the 3d edition of that work. – Ed.

25

See Table Talk, 2d edit. p. 283. Melancthon's words to Calvin are:

Tuo judicio prorsus assentior. Affirmu etiam vestros magistratus juste fecisse, quod hominem blasphemum, re ordine judicata, interfecerunt.

14th Oct. 1554. – Ed.

26

'But to circle the earth, as the heavenly bodies do,' &c. 'So we may see that the opinion of Copernicus touching the rotation of the earth, which astronomy itself cannot correct, because it is not repugnant to any of the phænomena, yet natural history may correct.'

Advancement of Learning, B. II. – Ed.

27

That Christ had a twofold being, natural and sacramental; that the Jews destroyed and sacrificed his natural being, and that Christian priests destroy and sacrifice in the Mass his sacramental being. – Ed.

28

Fides catholica, says Bellarmine, docet omnem virtutem esse bonam, omne vitium esse malum. Si autem erraret Papa præcipiendo vitia vel prohibendo virtutes, teneretur Ecclesia credere vitia esse bona et virtutes malas, nisi vellet contra conscientiam peccare.

De Pont. Roman. IV. 5. – Ed.

29

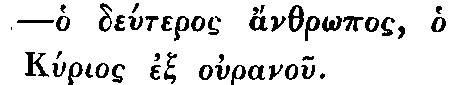

The ordinary Greek text is:

The Vulgate is:

primus homo de terra, terrenus; secundus homo de cœlis, cœlestis.

Ed.

30

The LXXX Sermons, fol. 1640. – Ed.

31

"Mr. Coleridge's admiration of Bull and Waterland as high theologians was very great. Bull he used to read in the Latin Defensio Fidei Nicoenoe, using the Jesuit Zola's edition of 1784, which, I think, he bought at Rome. He told me once, that when he was reading a Protestant English Bishop's work on the Trinity, in a copy edited by an Italian Jesuit in Italy, he felt proud of the Church of England, and in good humour with the Church of Rome."

Table Talk, 2d edit. p. 41. – Ed.

32

Rom. vi.3, 4, 5. – Ed.

33

John i 14. Gal. iv 4. Ed.

34

See the whole argument on the difference of the reason and the understanding, in the Aids to Reflection, 3d edit. pp. 206-227. Ed.

35

See the author's entire argument upon this subject in the Church and State. – Ed.

36

Galat. ii 20. – Ed.

37

Compare Hamlet, Act V. sc. 1. This sermon was preached, March 8, 1628-9. – Ed.

38

C. iii. 13, &c. – Ed.

39

See, however, the author's expressions at, I believe, a rather later period.

"I now think, after many doubts, that the passage; I know that my Redeemer liveth, &c. may fairly be taken as a burst of determination, a quasi prophecy. I know not how this can be; but in spite of all my difficulties, this I do know, that I shall be recompensed!"

Table Talk, 2d edit. p. 80. – Ed.

40

How so? Is it not admitted that Robert Stephens first divided the New Testament into verses in 1551? See the testimony to that effect of Henry Stephens, his son, in the Preface to his Concordance. – Ed.

41

Rom. viii. 3. Mr. C. afterwards expressed himself to the same effect:

"Christ's body, as mere body, or rather carcase (for body is an associated word), was no more capable of sin or righteousness than mine or yours; that his humanity had a capacity of sin, follows from its own essence. He was of like passions as we, and was tempted. How could he be tempted, if he had no formal capacity of being seduced?"

Table Talk, 2d edit. p. 261. – Ed.

42

See Hooker's admirable declaration of the doctrine: —

"These natures from the moment of their first combination have been and are for ever inseparable. For even when his soul forsook the tabernacle of his body, his Deity forsook neither body nor soul. If it had, then could we not truly hold either that the person of Christ was buried, or that the person of Christ did raise up itself from the dead. For the body separated from the Word can in no true sense be termed the person of Christ; nor is it true to say that the Son of God in raising up that body did raise up himself, if the body were not both with him and of him even during the time it lay in the sepulchre. The like is also to be said of the soul, otherwise we are plainly and inevitably Nestorians. The very person of Christ therefore for ever one and the self-same, was only touching bodily substance concluded within the grave, his soul only from thence severed, but by personal union his Deity still unseparably joined with both."

E. P. V. 52. 4. – Keble's edit. Ed.

43

xix. 41. – Ed.

44

(C.) which should be (B.)

"The object of the preceding discourse was to recommend the Bible as the end and centre of our reading and meditation. I can truly affirm of myself, that my studies have been profitable and availing to me only so far, as I have endeavored to use all my other knowledge as a glass enabling me to receive more light in a wider field of vision from the Word of God."

Ed.

45

Ep. 99. See Pearson, Art. v. – Ed.

46

Folio. 1708. – Ed.

47

Decem dierum vix mihi est familia. Heaut. v. i. – Ed.

48

Hendrick Nicholas and the Family of Love. – Ed.

49

Göttingen, 1821. The few following notes are, something out of order, inserted here in consequence of their connection with the immediately preceding remarks in the text. – Ed.

50

By Thomas Plume. Folio, 1676. – Ed.

51

Ea omnia super Christo Pilatus, et ipse jam pro sua conscientia Christianus, Cæsari tum Tiberio nuntiavit.

Apologet, ii. 624. See the account in Eusebius. Hist. Eccl. ii.2. – Ed.

52

See M. T. Ciceronis de Republica quæ supersunt. Zell. Stuttgardt. 1827. – Ed.

53

See supra. – Ed.

54

Folio. 1693. – Ed.

55

See The Church and State. – Ed.

56

The references are here given to Heber's edition, 1822. Ed.

57

The page however remains a blank. But a little essay on punctuation by the Author is in the Editor's possession, and will be published hereafter. – Ed.

58

See Euseb. Hist. iii. 27. – Ed.

59

'Vindication, &c. Quer.' 13, 14, 15. – Ed.

60

See the form previously exhibited in this volume, p. 93. Ed.

61

Mark viii. 29. Luke ix. 20. Ed.

62

1 Pet. v. 13. Ed.

63

Lightfoot and Wall use this strong argument for the lawfulness and implied duty of Infant Baptism in the Christian Church. It was the universal practice of the Jews to baptize the infant children of proselytes as well as their parents. Instead, therefore, of Christ's silence as to infants by name in his commission to baptize all nations being an argument that he meant to exclude them, it is a sign that he meant to include them. For it was natural that the precedent custom should prevail, unless it were expressly forbidden. The force of this, however, is limited to the ceremony; – its character and efficacy are not established by it. Ed.

64

The Author's views of Baptism are stated more fully and methodically in the Aids to Reflection; but even that statement is imperfect, and consequently open to objection, as was frequently admitted by Mr. C. himself. The Editor is unable to say what precise spiritual efficacy the Author ultimately ascribed to Infant Baptism; but he was certainly an advocate for the practice, and appeared as sponsor at the font for more than one of his friends' children. See his Letter to a Godchild, printed, for this purpose, at the end of this volume; his Sonnet on his Baptismal Birthday, (Poet. Works, ii. p. 151.) in the tenth line of which, in many copies, there was a misprint of 'heart' for 'front;' and the Table Talk, 2nd edit. p. 183. Ed.

65

Deut. xiii. 1-5. xviii. 22. Ed.

66

Galat. i. 8, 9. Ed.

67

Pp. 206-227. Ed.

68

With reference to all these notes on Original Sin, see Aids to Reflection, p. 250-286. – Ed.

69

Aids to Reflection, p. 274. – Ed.

70

Ante. 'Vindication, &c.' p. 357-8.

71

Ibid.

72

Dupliciter vero sanguis Christi et caro intelligitur, spiritualis ilia atque divina, de qua ipse dixit, Caro mea vere est cibus, &c., vel caro et sanguis, quæ crucifixa est, et qui militis effusus est lancea.

In Epist. Ephes. c. i.

73

See Table Talk, p. 72, second edit. Ed.

74

Ipsum regem tradunt, volventem commentaries Numæ, quum ibi occulta solennia sacrificia Jovi Elicio facta invenisset, operatum his sacris se abdidisse; sed non rite initum aut curatum id sacrum esse; nee solum nullam ei oblatam Cælestium speciem, sed ira Jovis, sollicitati prava religione, fulmine ictum cum domo conflagrasse.

L. i. c. xxxi. Ed.

75

"This also rests upon the practice apostolical and traditive interpretation of holy Church, and yet cannot be denied that so it ought to be, by any man that would not have his Christendom suspected. To these I add the communion of women, the distinction of books apocryphal from canonical, that such books were written by such Evangelists and Apostles, the whole tradition of Scripture itself, the Apostles' Creed, &c. … These and divers others of greater consequence, (which I dare not specify for fear of being misunderstood,) rely but upon equal faith with this of Episcopacy,"

&c. Ed.

76

S. xxvi.

77

S. iv. 4. Ed.

78

P. 98, &c. of the edition by Murray and Major, 1830 Ed.

79

Prefixed to an edition of the Pilgrim's Progress, by R. Edwards, 1820. – Ed.

80

The second of two 'Letters written to persons under trouble of mind.' Ed.

81

Sermon of the certainty and perpetuity of faith in the elect. Vol. iii. p. 583. Keale's edit. – Ed.

82

Of Queen's College, Cambridge, 1660.

83

See ante, p. 291. Ed.

84

He died on the 25th day of the same month.