полная версия

полная версияThe Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

Perhaps another want is a scheme of Christian psalmody fit for all our congregations, and which should not exceed 150 or 200 psalms and hymns. Surely if the Church does not hesitate in the titles of the Psalms and of the chapters of the Prophets to give the Christian sense and application, there can be no consistent objection to do the same in its spiritual songs. The effect on the morals, feelings, and information of the people at large is not to be calculated. It is this more than any other single cause that has saved the peasantry of Protestant Germany from the contagion of infidelity.

Ib. s. xvii. p. 325.

Thus the Holy Ghost brought to their memory all things which Jesus spake and did, and, by that means, we come to know all that the Spirit knew to be necessary for us.

Alas! it is one of the sad effects or results of the enslaving Old Bailey fashion of defending, or, as we may well call it, apologizing for, Christianity, – introduced by Grotius and followed up by the modern Alogi, whose wordless, lifeless, spiritless, scheme of belief it alone suits, – that we dare not ask, whether the passage here referred to must necessarily be understood as asserting a miraculous remembrancing, distinctly sensible by the Apostles; whether the gift had any especial reference to the composition of the Gospels; whether the assumption is indispensable to a well grounded and adequate confidence in the veracity of the narrators or the verity of the narration; if not, whether it does not unnecessarily entangle the faith of the acute and learned inquirer in difficulties, which do not affect the credibility of history in its common meaning – rather indeed confirm our reliance on its authority in all the points of agreement, that is, in every point which we are in the least concerned to know, – and expose the simple and unlearned Christian to objections best fitted to perplex, because easiest to be understood, and within the capacity of the shallowest infidel to bring forward and exaggerate; and lastly, whether the Scriptures must not be read in that faith which comes from higher sources than history, that is, if they are read to any good and Christian purpose. God forbid that I should become the advocate of mechanical infusions and possessions, superseding the reason and responsible will. The light a priori, in which, according to my conviction, the Scriptures must be read and tried, is no other than the earnest, What shall I do to be saved? with the inward consciousness, – the gleam or flash let into the inner man through the rent or cranny of the prison of sense, however produced by earthquake, or by decay, – as the ground and antecedent of the question; and with a predisposition towards, and an insight into, the a priori probability of the Christian dispensation as the necessary consequents. This is the holy spirit in us praying to the Spirit, without which no man can say that Jesus is the Lord: a text which of itself seems to me sufficient to cover the whole scheme of modern Unitarianism with confusion, when compared with that other, – I am the Lord (Jehovah): that is my name; and my glory will I not give to another. But in the Unitarian's sense of 'Lord,' and on his scheme of evidence, it might with equal justice be affirmed, that no man can say that Tiberius was the Emperor but by the Holy Ghost.

Ib. s. xxix. p. 331.

And that this is for this reason called a gift and grace, or issue of the Spirit, is so evident and notorious, that the speaking of an ordinary revealed truth, is called in Scripture, a speaking by the spirit, 1 Cor. xii. 8. No man can say that Jesus is the Lord but by the Holy Ghost. For, though the world could not acknowledge Jesus for the Lord without a revelation, yet now that we are taught this truth by Scripture, and by the preaching of the Apostles, to which they were enabled by the Holy Ghost, we need no revelation or enthusiasm to confess this truth, which we are taught in our creeds and catechisms, &c.

I do not, nay I dare not, hesitate to denounce this assertion as false in fact and the paralysis of all effective Christianity. A greater violence offered to Scripture words is scarcely conceivable. St. Paul asserts that no man can. Nay, says Taylor, every man that knows his catechism can; but unless some six or seven individuals had said it by the Holy Ghost some seventeen or eighteen hundred years ago, no man could say so.

Ib. s. xxxii. p. 334.

And yet, because the Holy Ghost renewed their memory, improved their understanding, supplied to some their want of human learning, and so assisted them that they should not commit an error in fact or opinion, neither in the narrative nor dogmatical parts, therefore they wrote by the spirit.

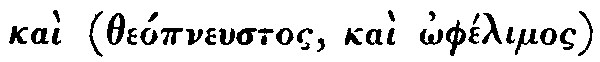

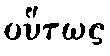

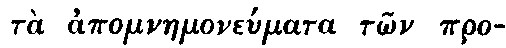

And where is the proof? – and to what purpose, unless a distinct and plain diagnostic were given of the divinities and the humanities which Taylor himself expressly admits in the text of the Scriptures? And even then what would it avail unless the interpreters and translators, not to speak of the copyists in the first and second centuries, were likewise assisted by inspiration? As to the larger part of the Prophetic books, and the whole of the Apocalypse, we must receive them as inspired truths, or reject them as simple inventions or enthusiastic delusions. But in what other book of Scripture does the writer assign his own work to a miraculous dictation or infusion? Surely the contrary is implied in St. Luke's preface. Does the hypothesis rest on one possible construction of a single passage in St. Paul, 2 Tim. iii. 16.? And that construction resting materially on a

Ib. s. li. p. 348.

So that let the devotion be ever so great, set forms of prayer will be expressive enough of any desire, though importunate as extremity itself.

This, and much of the same import in this treatise, is far more than Taylor, mature in experience and softened by afflictions, would have written. Besides, it is in effect, though not in logic, a deserting of his own strong and unshaken ground of the means and ends of public worship.

Ib. s. s. lxix. lxx. pp. 359-60.

These two sections are too much in the vague mythical style of the Italian and Jesuit divines, and the argument gives to these a greater advantage against our Church than it gains over the Sectarians in its support. We well know who and how many the compilers of our Liturgy were under Edward VI, and know too well what the weather-cock Parliaments were, both then and under Elizabeth, by which the compilation was made law. The argument therefore should be inverted; – not that the Church (A. B., C. D., F. L., &c.) compiled it; ergo, it is unobjectionable; but (and truly we may say it) it is so unobjectionable, so far transcending all we were entitled to expect from a few men in that state of information and such difficulties, that we are justified in concluding that the compilers were under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. But the same order holds good even with regard to the Scriptures. We cannot rightly affirm they were inspired, and therefore they must be believed; but they are worthy of belief, because excellent in so universal a sense to ends commensurate with the whole moral, and therefore the whole actual, world, that as sure as there is a moral Governor of the world, they must have been in some sense or other, and that too an efficient sense, inspired. Those who deny this, must be prepared to assert, that if they had what appeared to them good historic evidence of a miracle, in the world of the senses, they would receive the hideous immoral doctrines of Mahomet or Brahma, and thus disobey the express commands both of the Old and New Testament. Though an angel should come from heaven and work all miracles, yet preach another doctrine, we are to hold him accursed. Gal. i. 8.

Ib. s. lxxv. p. 356.

When Christ was upon the Mount, he gave it for a pattern, &c.

I cannot thoroughly agree with Taylor in all he says on this point. The Lord's Prayer is an encyclopedia of prayer, and of all moral and religious philosophy under the form of prayer. Besides this, that nothing shall be wanting to its perfection, it is itself singly the best and most divine of prayers. But had this been the main and primary purpose, it must have been thenceforward the only prayer permitted to Christians; and surely some distinct references to it would have been found in the Apostolic writings.

Ib. s. lxxx. p. 358.

Now then I demand, whether the prayer of Manasses be so good a prayer as the Lord's prayer? Or is the prayer of Judith, or of Tobias, or of Judas Maccabeus, or of the son of Sirach, is any of these so good? Certainly no man will say they are; and the reason is, because we are not sure they are inspired by the Holy Spirit of God.

How inconsistent Taylor often is, the result of the system of economizing truth! The true reason is the inverse. The prayers of Judith and the rest are not worthy to be compared with the Lord's Prayer; therefore neither is the spirit in which they were conceived worthy to be compared with the spirit from which the Lord's Prayer proceeded: and therefore with all fulness of satisfaction we receive the latter, as indeed and in fact our Lord's dictation.

In all men and in all works of great genius the characteristic fault will be found in the characteristic excellence. Thus in Taylor, fulness, overflow, superfluity. His arguments are a procession of all the nobles and magnates of the land in their grandest, richest, and most splendid paraphernalia: but the total impression is weakened by the multitudes of lacqueys and ragged intruders running in and out between the ranks. As far as the Westminster divines were the antagonists to be answered – and with the exception of these, and those who like Baxter, Calamy, and Bishop Reynolds, contended for a reformation or correction only of the Church Liturgy, there were none worth answering, – the question was, not whether the use of one and the same set of prayers on all days in all churches was innocent, but whether the exclusive imposition of the same was comparatively expedient and conducive to edification?

Let us not too severely arraign the judgment or the intentions of the good men who determined for the negative. If indeed we confined ourselves to the comparison between our Liturgy, and any and all of the proposed substitutes for it, we could not hesitate: but those good men, in addition to their prejudices, had to compare the lives, the conversation, and the religious affections and principles of the prelatic and anti-prelatic parties in general.

And do not we ourselves now do the like? Are we not, and with abundant reason, thankful that Jacobinism is rendered comparatively feeble and its deadly venom neutralized, by the profligacy and open irreligion of the majority of its adherents? Add the recent cruelties of the Star Chamber under Laud; – (I do not say the intolerance; for that which was common to both parties, must be construed as an error in both, rather than a crime in either); – and do not forget the one great inconvenience to which the prelatic divines were exposed from the very position which it was the peculiar honor of the Church of England to have taken and maintained, namely, the golden mean; – (for in consequence of this their arguments as Churchmen would often have the appearance of contrasting with their grounds of controversy as Protestants,) – and we shall find enough to sanction our charity as brethren, without detracting a tittle from our loyalty as members of the established Church.

As to this Apology, the victory doubtless remains with Taylor on the whole; but to have rendered it full and triumphant, it would have been necessary to do what perhaps could not at that time, and by Jeremy Taylor, have been done with prudence; namely, not only to disprove in part, but likewise in part to explain, the alleged difference of the spiritual fruits in the ministerial labors of the high and low party in the Church, – (for remember that at this period both parties were in the Church, even as the Evangelical, Reformed and Pontifical parties before the establishment of a schism by the actually schismatical Council of Trent,) – and thus to demonstrate that the differences to the disadvantage of the established Church, as far as they were real, were as little attributable to the Liturgy, as the wound in the heel of Achilles to the shield and breast-plate which his immortal mother had provided for him from the forge divine.

Ib. s. lxxxvi. p. 361.

That the Apostles did use the prayer their Lord taught them, I think needs not much be questioned.

Ad contra, see above. But that they did not till the siege of Jerusalem deviate unnecessarily from the established usage of the Synagogue is beyond rational doubt. We may therefore safely maintain that a set form was sanctioned by Apostolic practice; though the form was probably settled after the converts from Paganism began to be the majority of Christians.

Ib. s. lxxxvii. p. 361.

Now that they tied themselves to recitation of the very words of Christ's prayer pro loco et tempore, I am therefore easy to believe, because I find they were strict to a scruple in retaining the sacramental words which Christ spake when he instituted the blessed Sacrament.

Not a case in point. Besides it assumes the controverted sense of

Ib. s. lxxxviii. p. 362.

And I the rather make the inference from the preceding argument because of the cognation one hath with the other; for the Apostles did also in the consecration of the Eucharist use the Lord's Prayer; and that together with the words of institution was the only form of consecration, saith St. Gregory; and St. Jerome affirms, that the Apostles, by the command of their Lord, used this prayer in the benediction of the elements.

This section is an instance of impolitic management of a cause, into which Jeremy Taylor was so often seduced by the fertility of his intellect and the opulence of his erudition. An antagonist by exposing the improbability of the tradition, (and most improbable it surely is), and the little credit due to Saint Gregory and Saint Jerome (not forgetting a Miltonic sneer at their saintship), might draw off the attention from the unanswerable parts of Taylor's reasoning and leave an impression of his having been confuted.

Ib. s. lxxxix. p. 362.

But besides this, when the Apostles had received great measures of the spirit, and by their gift of prayer composed more forms for the help and comfort of the Church, &c.

Who would not suppose, that the first two lines were an admitted point of history, instead of a bare conjecture in the form of a bold assertion? O, dearest man! so excellent a cause did not need such Bellarminisms.

Ib. p. 363.

And the Fathers of the Council of Antioch complain against Paulus Samosatenus, quod Psalmos et cantus, qui ad Domini nostri Jesu Christi honorem decantari solent, tanquam recentiores, et a viris recentioris memorioe editos, exploserit.

This Sam-in-satin-hose, or Paul, the same-as-Satan-is, might, I think, have found his confutation in Pliny's Letter to Trajan. Carmen Christo, quasi Deo, dicere secum invicem.

Ib. s. xc. p. 364.

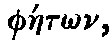

Which together with the

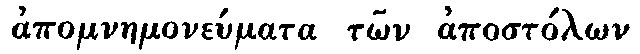

An ingenious but not tenable solution of Justin Martyr's

Ib. s. xci. pp. 364-5.

For the offices of prose we find but small mention of them in the very first time, save only in general terms, and that such there were, and that St. James, St. Mark, St. Peter, and others of the Apostles and Apostolical men, made Liturgies; and if these which we have at this day were not theirs, yet they make probation that these Apostles left others, or else they were impudent people that prefixed their names so early, and the Churches were very incurious to swallow such a bole, if no pretension could have been reasonably made for their justification.

A rash and dangerous argument. 1810.

A many-edged weapon, which might too readily be turned against the common faith by the common enemy. For if these Liturgies were rightly attributed to St. James, St. Mark, St. Peter, and others of the Apostles and Apostolical men, how could they have been superseded? How could the Church have excluded them from the Canon? But if falsely, and yet for a time and at so early an age generally believed to have been composed by St. James and the rest, it is to be feared that the difference will not stop at the point to which Paul of Samosata carried it; – a fearful consideration for a Christian of the Grotian and Paleyan school. It would not, however, shake my nerves, I confess. The Epistles of St. Paul, and the Gospel, Epistles, and Apocalypse of St. John, contain an evidence of their authenticity, which no uncertainty of ecclesiastic history, no proof of the frequency and success of forgery or ornamental titles (as the Wisdom of Solomon) mistaken for matter of fact, can wrest from me; and with these for my guides and sanctions, what one article of Christian faith could be taken from me, or even unsettled? It seems to me, as it did to Luther, incomparably more probable that the eloquent treatise, entitled an Epistle to the Hebrews, was written by Apollos than by Paul; and what though it was written by neither? It is demonstrable that it was composed before the siege of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple; and scarcely less satisfactory is the internal evidence that it was composed by an Alexandrian. These two data are sufficient to establish the fact, that the Pauline doctrine at large was common to all Christians at that early period, and therefore the faith delivered by Christ. And this is all I want; nor this for my own assurance, but as arming me with irrefragable arguments against those psilanthropists who as falsely, as arrogantly, call themselves Unitarians, on the one hand; and against the infidel fiction, that Christianity owes its present shape to the genius and rabbinical cabala of Paul on the other: while at the same time it weakens the more important half of the objection to, or doubt concerning, the authenticity of St. Peter's Epistles. To this too I attach a high controversial value (for the beauty and excellence of the Epistles themselves are not affected by the question); and I receive them as authentic, for they have all the circumstantial evidence that I have any right to expect. But I feel how much more genial my conviction would become, should I discover, or have pointed out to me, any positive internal evidence equivalent to that which determines the date of the Epistle to the Hebrews, or even to that which leaves no doubt on my mind that the writer was an Alexandrian Jew. This, my dear Lamb, is one of the advantages which the previous evidence supplied by the reason and the conscience secures for us. We learn what in its nature passes all understanding, and what belongs to the understanding, and on which, therefore, the understanding may and ought to act freely and fearlessly: while those who will admit nothing above the understanding