полная версия

полная версияArrows of the Chace, vol. 1/2

2. To accomplish the second object is the main difficulty. Touching which I venture positively to state:

First. That sound criticism of art is impossible to young men, for it consists principally, and in a far more exclusive sense than has yet been felt, in the recognition of the facts represented by the art. A great artist represents many and abstruse facts; it is necessary, in order to judge of his works, that all those facts should be experimentally (not by hearsay) known to the observer; whose recognition of them constitutes his approving judgment. A young man cannot know them.

Criticism of art by young men must, therefore, consist either in the more or less apt retailing and application of received opinions, or in a more or less immediate and dextrous use of the knowledge they already possess, so as to be able to assert of given works of art that they are true up to a certain point; the probability being then that they are true farther than the young man sees.

The first kind of criticism is, in general, useless, if not harmful; the second is that which the youths will employ who are capable of becoming critics in after years.

Secondly. All criticism of art, at whatever period of life, must be partial; warped more or less by the feelings of the person endeavoring to judge. Certain merits of art (as energy, for instance) are pleasant only to certain temperaments; and certain tendencies of art (as, for instance, to religious sentiment) can only be sympathized with by one order of minds. It is almost impossible to conceive of any mode of examination which would set the students on anything like equitable footing in such respects; but their sensibility to art may be generally tested.

Thirdly. The history of art, or the study, in your accurate words, “about the subject,” is in no wise directly connected with the studies which promote or detect art-capacity or art-judgment. It is quite possible to acquire the most extensive and useful knowledge of the forms of art existing in different ages, and among different nations, without thereby acquiring any power whatsoever of determining respecting any of them (much less respecting a modern work of art) whether it is good or bad.

These three facts being so, we had perhaps best consider, first, what direction the art studies of the youth should take, as that will at once regulate the mode of examination.

First. He should be encouraged to carry forward the practical power of drawing he has acquired in the elementary school. This should be done chiefly by using that power as a help in other work: precision of touch should be cultivated by map-drawing in his geography class; taste in form by flower-drawing in the botanical schools; and bone and limb drawing in the physiological schools. His art, kept thus to practical service, will always be right as far as it goes; there will be no affectation or shallowness in it. The work of the drawing-master would be at first little more than the exhibition of the best means and enforcement of the most perfect results in the collateral studies of form.

Secondly. His critical power should be developed by the presence around him of the best models, into the excellence of which his knowledge permits him to enter. He should be encouraged, above all things, to form and express judgment of his own; not as if his judgment were of any importance as related to the excellence of the thing, but that both his master and he may know precisely in what state his mind is. He should be told of an Albert Dürer engraving, “That is good, whether you like it or not; but be sure to determine whether you do or do not, and why.” All formal expressions of reasons for opinion, such as a boy could catch up and repeat, should be withheld like poison; and all models which are too good for him should be kept out of his way. Contemplation of works of art without understanding them jades the faculties and enslaves the intelligence. A Rembrandt etching is a better example to a boy than a finished Titian, and a cast from a leaf than one of the Elgin marbles.

Thirdly. I would no more involve the art-schools in the study of the history of art than surgical schools in that of the history of surgery. But a general idea of the influence of art on the human mind ought to be given by the study of history in the historical schools; the effect of a picture, and power of a painter, being examined just as carefully (in relation to its extent) as the effect of a battle and the power of a general. History, in its full sense, involves subordinate knowledge of all that influences the acts of mankind; it has hardly yet been written at all, owing to the want of such subordinate knowledge in the historians; it has been confined either to the relation of events by eye-witnesses (the only valuable form of it), or the more or less ingenious collation of such-relations. And it is especially desirable to give history a more archæological range at this period, so that the class of manufactures produced by a city at a given date should be made of more importance in the student’s mind than the humors of the factions that governed, or details of the accidents that preserved it, because every day renders the destruction of historical memorials more complete in Europe owing to the total want of interest in them felt by its upper and middle classes.

Fourthly. Where the faculty for art was special, it ought to be carried forward to the study of design, first in practical application to manufacture, then in higher branches of composition. The general principles of the application of art to manufacture should be explained in all cases, whether of special or limited faculty. Under this head we may at once get rid of the third question stated in the first page—how to detect special gift. The power of drawing from a given form accurately would not be enough to prove this: the additional power of design, with that of eye for color, which could be tested in the class concerned with manufacture, would justify the master in advising and encouraging the youth to undertake special pursuit of art as an object of life.

It seems easy, on the supposition of such a course of study, to conceive a mode of examination which would test relative excellence. I cannot suggest the kind of questions which ought to be put to the class occupied with sculpture; but in my own business of painting, I should put, in general, such tasks and questions as these:

(1) “Sketch such and such an object” (given a difficult one, as a bird, complicated piece of drapery, or foliage) “as completely as you can in light and shade in half an hour.”

(2) “Finish such and such a portion of it” (given a very small portion) “as perfectly as you can, irrespective of time.”

(3) “Sketch it in color in half an hour.”

(4) “Design an ornament for a given place and purpose.”

(5) “Sketch a picture of a given historical event in pen and ink.”

(6) “Sketch it in colors.”

(7) “Name the picture you were most interested in in the Royal Academy Exhibition of this year. State in writing what you suppose to be its principal merits—faults—the reasons of the interest you took in it.”

I think it is only the fourth of these questions which would admit of much change; and the seventh, in the name of the exhibition; the question being asked, without previous knowledge by the students, respecting some one of four or five given exhibitions which should be visited before the Examination.

This being my general notion of what an Art-Examination should be, the second great question remains of the division of schools and connection of studies.

Now I have not yet considered—I have not, indeed, knowledge enough to enable me to consider—what the practical convenience or results of given arrangements would be. But the logical and harmonious arrangement is surely a simple one; and it seems to me as if it would not be inconvenient, namely (requiring elementary drawing with arithmetic in the preliminary Examination), that there should then be three advanced schools:

A. The School of Literature (occupied chiefly in the study of human emotion and history).

B. The School of Science (occupied chiefly in the study of external facts and existences of constant kind).

C. The School of Art (occupied in the development of active and productive human faculties).

In the school A, I would include Composition in all languages, Poetry, History, Archæology, Ethics.

In the school B, Mathematics, Political Economy, the Physical Sciences (including Geography and Medicine).

In the school C, Painting, Sculpture, including Architecture, Agriculture, Manufacture, War, Music, Bodily Exercises (Navigation in seaport schools), including laws of health.

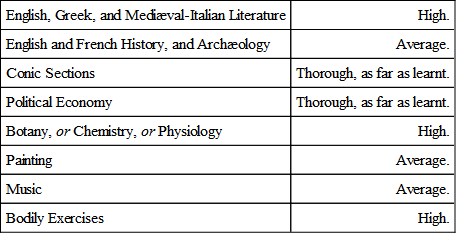

I should require, for a first class, proficiency in two schools; not, of course, in all the subjects of each chosen school, but in a well-chosen and combined group of them. Thus, I should call a very good first-class man one who had got some such range of subjects, and such proficiency in each, as this:

I have written you a sadly long letter, but I could not manage to get it shorter.

Believe me, my dear Sir,Very faithfully and respectfully yours,J. Ruskin.Rev. F. Temple.

Perhaps I had better add what to you, but not to every one who considers such a scheme of education, would be palpable—that the main value of it would be brought out by judicious involution of its studies. This, for instance, would be the kind of Examination Paper I should hope for in the Botanical Class:

1. State the habit of such and such a plant.

2. Sketch its leaf, and a portion of its ramifications (memory).

3. Explain the mathematical laws of its growth and structure.

4. Give the composition of its juices in different seasons.

5. Its uses? Its relations to other families of plants, and conceivable uses beyond those known?

6. Its commercial value in London? Mode of cultivation?

7. Its mythological meaning? The commonest or most beautiful fables respecting it?

8. Quote any important references to it by great poets.

9. Time of its introduction.

10. Describe its consequent influence on civilization.

Of all these ten questions, there is not one which does not test the student in other studies than botany. Thus, 1, Geography; 2, Drawing; 3, Mathematics; 4, 5, Chemistry; 6, Political Economy; 7, 8, 9, 10, Literature.

Of course the plants required to be thus studied could be but few, and would rationally be chosen from the most useful of foreign plants, and those common and indigenous in England. All sciences should, I think, be taught more for the sake of their facts, and less for that of their system, than heretofore. Comprehensive and connected views are impossible to most men; the systems they learn are nothing but skeletons to them; but nearly all men can understand the relations of a few facts bearing on daily business, and to be exemplified in common substances. And science will soon be so vast that the most comprehensive men will still be narrow, and we shall see the fitness of rather teaching our youth to concentrate their general intelligence highly on given points than scatter it towards an infinite horizon from which they can fetch nothing, and to which they can carry nothing.

[From “Nature and Art,” December 1, 1866.]

ART-TEACHING BY CORRESPONDENCE

Dear Mr. Williams:32 I like your plan of teaching by letter exceedingly: and not only so, but have myself adopted it largely, with the help of an intelligent under-master, whose operations, however, so far from interfering with, you will much facilitate, if you can bring this literary way of teaching into more accepted practice. I wish we had more drawing-masters who were able to give instruction definite enough to be expressed in writing: many can teach nothing but a few tricks of the brush, and have nothing to write, because nothing to tell.

With every wish for your success,—a wish which I make quite as much in your pupils’ interest as in your own,—

Believe me, always faithfully yours,J. Ruskin.Denmark Hill, November, 1860.II.

PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS AND THE NATIONAL GALLERY

[From “The Times,” January 7, 1847.]

DANGER TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY. 33

To the Editor of “The Times.”

Sir: As I am sincerely desirous that a stop may be put to the dangerous process of cleaning lately begun in our National Gallery, and as I believe that what is right is most effectively when most kindly advocated, and what is true most convincingly when least passionately asserted, I was grieved to see the violent attack upon Mr. Eastlake in your columns of Friday last; yet not less surprised at the attempted defence which appeared in them yesterday.34 The outcry which has arisen upon this subject has been just, but it has been too loud; the injury done is neither so great nor so wilful as has been asserted, and I fear that the respect which might have been paid to remonstrance may be refused to clamor.

I was inclined at first to join as loudly as any in the hue and cry. Accustomed, as I have been, to look to England as the refuge of the pictorial as of all other distress, and to hope that, having no high art of her own, she would at least protect what she could not produce, and respect what she could not restore, I could not but look upon the attack which has been made upon the pictures in question as on the violation of a sanctuary. I had seen in Venice the noblest works of Veronese painted over with flake-white with a brush fit for tarring ships; I had seen in Florence Angelico’s highest inspiration rotted and seared into fragments of old wood, burnt into blisters, or blotted into glutinous maps of mildew;35 I had seen in Paris Raphael restored by David and Vernet; and I returned to England in the one last trust that, though her National Gallery was an European jest, her art a shadow, and her connoisseurship an hypocrisy, though she neither knew how to cherish nor how to choose, and lay exposed to the cheats of every vender of old canvas—yet that such good pictures as through chance or oversight might find their way beneath that preposterous portico, and into those melancholy and miserable rooms, were at least to be vindicated thenceforward from the mercy of republican, priest, or painter, safe alike from musketry, monkery, and manipulation.

But whatever pain I may feel at the dissipation of this dream, I am not disposed altogether to deny the necessity of some illuminatory process with respect to pictures exposed to a London atmosphere and populace. Dust an inch thick, accumulated upon the panes in the course of the day, and darkness closing over the canvas like a curtain, attest too forcibly the influence on floor and air of the “mutable, rank-scented, many.” It is of little use to be over-anxious for the preservation of pictures which we cannot see; the only question is, whether in the present instance the process may not have been carried perilously far, and whether in future simpler and safer means may not be adopted to remove the coat of dust and smoke, without affecting either the glazing of the picture, or, what is almost as precious, the mellow tone left by time.

As regards the “Peace and War,”36 I have no hesitation in asserting that for the present it is utterly and forever partially destroyed. I am not disposed lightly to impugn the judgment of Mr. Eastlake, but this was indisputably of all the pictures in the Gallery that which least required, and least could endure, the process of cleaning. It was in the most advantageous condition under which a work of Rubens can be seen; mellowed by time into more perfect harmony than when it left the easel, enriched and warmed, without losing any of its freshness or energy. The execution of the master is always so bold and frank as to be completely, perhaps even most agreeably, seen under circumstances of obscurity, which would be injurious to pictures of greater refinement; and, though this was, indeed, one of his most highly finished and careful works (to my mind, before it suffered this recent injury, far superior to everything at Antwerp, Malines, or Cologne), this was a more weighty reason for caution than for interference. Some portions of color have been exhibited which were formerly untraceable; but even these have lost in power what they have gained in definiteness—the majesty and preciousness of all the tones are departed, the balance of distances lost. Time may perhaps restore something of the glow, but never the subordination; and the more delicate portions of flesh tint, especially the back of the female figure on the left, and of the boy in the centre, are destroyed forever.

The large Cuyp37 is, I think, nearly uninjured. Many portions of the foreground painting have been revealed, which were before only to be traced painfully, if at all. The distance has indeed lost the appearance of sunny haze, which was its chief charm, but this I have little doubt it originally did not possess, and in process of time may recover.

The “Bacchus and Ariadne”38 of Titian has escaped so scot free that, not knowing it had been cleaned, I passed it without noticing any change. I observed only that the blue of the distance was more intense than I had previously thought it, though, four years ago, I said of that distance that it was “difficult to imagine anything more magnificently impossible, not from its vividness, but because it is not faint and aërial enough to account for its purity of color. There is so total a want of atmosphere in it, that but for the difference of form it would be impossible to distinguish the mountains from the robe of Ariadne.”39

Your correspondent is alike unacquainted with the previous condition of this picture, and with the character of Titian distances in general, when he complains of a loss of aërial quality resulting in the present case from cleaning.

I unfortunately did not see the new Velasquez40 until it had undergone its discipline; but I have seldom met with an example of the master which gave me more delight, or which I believe to be in more genuine or perfect condition. I saw no traces of the retouching which is hinted at by your correspondent “Verax,” nor are the touches on that canvas such as to admit of very easy or untraceable interpolation of meaner handling. His complaint of loss of substance in the figures of the foreground is, I have no doubt, altogether groundless. He has seen little southern scenery if he supposes that the brilliancy and apparent nearness of the silver clouds is in the slightest degree overcharged; and shows little appreciation of Velasquez in supposing him to have sacrificed the solemnity and might of such a distance to the inferior interest of the figures in the foreground. Had he studied the picture attentively, he might have observed that the position of the horizon suggests, and the lateral extent of the foreground proves, such a distance between the spectator and even its nearest figures as may well justify the slightness of their execution.

Even granting that some of the upper glazings of the figures had been removed, the tone of the whole picture is so light, gray, and glittering, and the dependence on the power of its whites so absolute, that I think the process hardly to be regretted which has left these in lustre so precious, and restored to a brilliancy which a comparison with any modern work of similar aim would render apparently supernatural, the sparkling motion of its figures and the serene snow of its sky.

I believe I have stated to its fullest extent all the harm that has yet been done, yet I earnestly protest against any continuance of the treatment to which these pictures have been subjected. It is useless to allege that nothing but discolored varnish has been withdrawn, for it is perfectly possible to alter the structure and continuity, and so destroy the aërial relations of colors of which no part has been removed. I have seen the dark blue of a water-color drawing made opaque and pale merely by mounting it; and even supposing no other injury were done, every time a picture is cleaned it loses, like a restored building, part of its authority; and is thenceforward liable to dispute and suspicion, every one of its beauties open to question, while its faults are screened from accusation. It cannot be any more reasoned from with security; for, though allowance may be made for the effect of time, no one can calculate the arbitrary and accidental changes occasioned by violent cleaning. None of the varnishes should be attacked; whatever the medium used, nothing but soot and dust should be taken away, and that chiefly by delicate and patient friction; and, in order to protract as long as possible the necessity even for this all the important pictures in the gallery should at once be put under glass,41 and closed, not merely by hinged doors, like the Correggio, but permanently and securely. I should be glad to see this done in all rich galleries, but it is peculiarly necessary in the case of pictures exposed in London, and to a crowd freely admitted four days in the week; it would do good also by necessitating the enlargement of the rooms, and the bringing down of all the pictures to the level of the eye. Every picture that is worth buying or retaining is worth exhibiting in its proper place, and if its scale be large, and its handling rough, there is the more instruction to be gained by close study of the various means adopted by the master to secure his distant effect. We can certainly spare both the ground and the funds which would enable us to exhibit pictures for which no price is thought too large, and for all purposes of study and for most of enjoyment pictures are useless when they are even a little above the line. The fatigue complained of by most persons in examining a picture gallery is attributable, not only to the number of works, but to their confused order of succession, and to the straining of the sight in endeavoring to penetrate the details of those above the eye. Every gallery should be long enough to admit of its whole collection being hung in one line, side by side, and wide enough to allow of the spectators retiring to the distance at which the largest picture was intended to be seen. The works of every master should be brought together and arranged in chronological order; and such drawings or engravings as may exist in the collection, either of, or for, its pictures, or in any way illustrative of them, should be placed in frames opposite each, in the middle of the room.

But, Sir, the subjects of regret connected with the present management of our national collection are not to be limited either to its treatment or its arrangement. The principles of selection which have been acted upon in the course of the last five or six years have been as extraordinary as unjustifiable. Whatever may be the intrinsic power, interest, or artistical ability of the earlier essays of any school of art, it cannot be disputed that characteristic examples of every one of its most important phases should form part of a national collection: granting them of little value individually, their collective teaching is of irrefragable authority; and the exhibition of perfected results alone, while the course of national progress through which these were reached is altogether concealed, is more likely to discourage than to assist the efforts of an undeveloped school. Granting even what the shallowest materialism of modern artists would assume, that the works of Perugino were of no value, but as they taught Raphael; that John Bellini is altogether absorbed and overmastered by Titian; that Nino Pisano was utterly superseded by Bandinelli or Cellini, and Ghirlandajo sunk in the shadow of Buonaroti: granting Van Eyck to be a mere mechanist, and Giotto a mere child, and Angelico a superstitious monk, and whatever you choose to grant that ever blindness deemed or insolence affirmed, still it is to be maintained and proved, that if we wish to have a Buonaroti or a Titian of our own, we shall with more wisdom learn of those of whom Buonaroti and Titian learned, and at whose knees they were brought up, and whom to their day of death they ever revered and worshipped, than of those wretched pupils and partisans who sank every high function of art into a form and a faction, betrayed her trusts, darkened her traditions, overthrew her throne, and left us where we are now, stumbling among its fragments. Sir, if the canvases of Guido, lately introduced into the gallery,42 had been works of the best of those pupils, which they are not; if they had been good works of even that bad master, which they are not; if they had been genuine and untouched works, even though feeble, which they are not; if, though false and retouched remnants of a feeble and fallen school, they had been endurably decent or elementarily instructive—some conceivable excuse might perhaps have been by ingenuity forged, and by impudence uttered, for their introduction into a gallery where we previously possessed two good Guidos,43 and no Perugino (for the attribution to him of the wretched panel which now bears his name is a mere insult), no Angelico, no Fra Bartolomeo, no Albertinelli, no Ghirlandajo, no Verrochio, no Lorenzo di Credi—(what shall I more say, for the time would fail me?) But now, Sir, what vestige of apology remains for the cumbering our walls with pictures that have no single virtue, no color, no drawing, no character, no history, no thought? Yet 2,000 guineas were, I believe, given for one of those encumbrances, and 5,000 for the coarse and unnecessary Rubens,44 added to a room half filled with Rubens before, while a mighty and perfect work of Angelico was sold from Cardinal Fesch’s collection for 1,500.45 I do not speak of the spurious Holbein,46 for though the veriest tyro might well be ashamed of such a purchase, it would have been a judicious addition had it been genuine; so was the John Bellini, so was the Van Eyck; but the mighty Venetian master, who alone of all the painters of Italy united purity of religious aim with perfection of artistical power, is poorly represented by a single head;47 and I ask, in the name of the earnest students of England, that the funds set apart for her gallery may no longer be played with like pebbles in London auction-rooms. Let agents be sent to all the cities of Italy; let the noble pictures which are perishing there be rescued from the invisibility and ill-treatment which their position too commonly implies, and let us have a national collection which, however imperfect, shall be orderly and continuous, and shall exhibit with something like relative candor and justice the claims to our reverence of those great and ancient builders, whose mighty foundation has been for two centuries concealed by wood, and hay, and stubble, the distorted growing, and thin gleaning of vain men in blasted fields.