полная версия

полная версияArrows of the Chace, vol. 1/2

The question, therefore, is one of terms rather than of things; and before proceeding it will be necessary for me to make your correspondent understand thoroughly what is meant by the term shadow as opposed to that of reflection.

Let us stand on the sea-shore on a cloudless night, with a full moon over the sea, and a swell on the water. Of course a long line of splendor will be seen on the waves under the moon, reaching from the horizon to our very feet. But are those waves between the moon and us actually more illuminated than any other part of the sea? Not one whit. The whole surface of the sea is under the same full light, but the waves between the moon and us are the only ones which are in a position to reflect that light to our eyes. The sea on both sides of that path of light is in perfect darkness—almost black. But is it so from shadow? Not so, for there is nothing to intercept the moonlight from it: it is so from position, because it cannot reflect any of the rays which fall on it to our eyes, but reflects instead the dark vault of the night sky. Both the darkness and the light on it, therefore—and they are as violently contrasted as may well be—are nothing but reflections, the whole surface of the water being under one blaze of moonlight, entirely unshaded by any intervening object whatsoever.

Now, then, we can understand the cause of the chiaro-scuro of the sea by daylight with lateral sun. Where the sunlight reaches the water, every ripple, wave, or swell reflects to the eye from some of its planes either the image of the sun or some portion of the neighboring bright sky. Where the cloud interposes between the sun and sea, all these luminous reflections are prevented, and the raised planes of the waves reflect only the dark under-surface of the cloud; and hence, by the multiplication of the images, spaces of light and shade are produced, which lie on the sea precisely in the position of real or positive light and shadows—corresponding to the outlines of the clouds—laterally cast, and therefore seen in addition to, and at the same time with, the ordinary or direct reflection, vigorously contrasted, the lights being often a blaze of gold, and the shadows a dark leaden gray; and yet, I repeat, they are no more real lights, or real shadows, on the sea, than the image of a black coat is a shadow on a mirror, or the image of white paper a light upon it.188

Are there, then, no shadows whatsoever upon the sea? Not so. My assertion is simply that there are none on clear water near the eye. I shall briefly state a few of the circumstances which give rise to real shadow in distant effect.

I. Any admixture of opaque coloring matter, as of mud, chalk, or powdered granite renders water capable of distinct shadow, which is cast on the earthy and solid particles suspended in the liquid. None of the seas on our south-eastern coast are so clear as to be absolutely incapable of shade; and the faint tint, though scarcely perceptible to a near observer,189 is sufficiently manifest when seen in large extent from a distance, especially when contrasted, as your correspondent says, with reflected lights. This was one reason for my introducing the words—“near the eye.”

There is, however, a peculiarity in the appearances of such shadows which requires especial notice. It is not merely the transparency of water, but its polished surface, and consequent reflective power, which render it incapable of shadow. A perfectly opaque body, if its power of reflection be perfect, receives no shadow (this I shall presently prove); and therefore, in any lustrous body, the incapability of shadow is in proportion to the power of reflection. Now the power of reflection in water varies with the angle of the impinging ray, being of course greatest when that angle is least: and thus, when we look along the water at a low angle, its power of reflection maintains its incapability of shadow to a considerable extent, in spite of its containing suspended opaque matter; whereas, when we look down upon water from a height, as we then receive from it only rays which have fallen on it at a large angle, a great number of those rays are unreflected from the surface, but penetrate beneath the surface, and are then reflected190 from the suspended opaque matter: thus rendering shadows clearly visible which, at a small angle, would have been altogether unperceived.

II. But it is not merely the presence of opaque matter which renders shadows visible on the sea seen from a height. The eye, when elevated above the water, receives rays reflected from the bottom, of which, when near the water, it is insensible. I have seen the bottom at seven fathoms, so that I could count its pebbles, from the cliffs of the Cornish coast; and the broad effect of the light and shade of the bottom is discernible at enormous depths. In fact, it is difficult to say at what depth the rays returned from the bottom become absolutely ineffective—perhaps not until we get fairly out into blue water. Hence, with a white or sandy shore, shadows forcible enough to afford conspicuous variety of color may be seen from a height of two or three hundred feet.

III. The actual color of the sea itself is an important cause of shadow in distant effect. Of the ultimate causes of local color in water I am not ashamed to confess my total ignorance, for I believe Sir David Brewster himself has not elucidated them. Every river in Switzerland has a different hue. The lake of Geneva, commonly blue, appears, under a fresh breeze, striped with blue and bright red; and the hues of coast-sea are as various as those of a dolphin; but, whatever be the cause of their variety, their intensity is, of course, dependent on the presence of sun-light. The sea under shade is commonly of a cold gray hue; in sun-light it is susceptible of vivid and exquisite coloring: and thus the forms of clouds are traced on its surface, not by light and shade, but by variation of color by grays opposed to greens, blues to rose-tints, etc. All such phenomena are chiefly visible from a height and a distance; and thus furnished me with additional reasons for introducing the words—“near the eye.”

IV. Local color is, however, the cause of one beautiful kind of chiaro-scuro, visible when we are close to the water—shadows cast, not on the waves, but through them, as through misty air. When a wave is raised so as to let the sun-light through a portion of its body, the contrast of the transparent chrysoprase green of the illuminated parts with the darkness of the shadowed is exquisitely beautiful.

Hitherto, however, I have been speaking chiefly of the transparency of water as the source of its incapability of shadow. I have still to demonstrate the effect of its polished surface.

Let your correspondent pour an ounce or two of quicksilver into a flat white saucer, and, throwing a strip of white paper into the middle of the mercury, as before into the water, interpose an upright bit of stick between it and the sun: he will then have the pleasure of seeing the shadow of the stick sharply defined on the paper and the edge of the saucer, while on the intermediate portion of mercury it will be totally invisible191. Mercury is a perfectly opaque body, and its incapability of shadow is entirely owing to the perfection of its polished surface. Thus, then, whether water be considered as transparent or reflective (and according to its position it is one or the other, or partially both—for in the exact degree that it is the one, it is not the other), it is equally incapable of shadow. But as on distant water, so also on near water, when broken, pseudo shadows take place, which are in reality nothing more than the aggregates of reflections. In the illuminated space of the wave, from every plane turned towards the sun there flashes an image of the sun; in the un-illuminated space there is seen on every such plane only the dark image of the interposed body. Every wreath of the foam, every jet of the spray, reflects in the sunlight a thousand diminished suns, and refracts their rays into a thousand colors; while in the shadowed parts the same broken parts of the wave appear only in dead, cold white; and thus pseudo shadows are caused, occupying the position of real shadows, defined in portions of their edge with equal sharpness: and yet, I repeat, they are no more real shadows than the image of a piece of black cloth is a shadow on a mirror.

But your correspondent will say, “What does it matter to me, or to the artist, whether they are shadows or not? They are darkness, and they supply the place of shadows, and that it is all I contend for.” Not so. They do not supply the place of shadows; they are divided from them by this broad distinction, that while shadow causes uniform deepening of the ground-tint in the objects which it affects, these pseudo shadows are merely portions of that ground-tint itself undeepened, but cut out and rendered conspicuous by flashes of light irregularly disposed around it. The ground-tint both of shadowed and illumined parts is precisely the same—a pure pale gray, catching as it moves the hues of the sky and clouds; but on this, in the illumined spaces, there fall touches and flashes of intense reflected light, which are absent in the shadow. If, for the sake of illustration, we consider the wave as hung with a certain quantity of lamps, irregularly disposed, the shape and extent of a shadow on that wave will be marked by the lamps being all put out within its influence, while the tint of the water itself is entirely unaffected by it.

The works of Stanfield will supply your correspondent with perfect and admirable illustrations of this principle. His water-tint is equally clear and luminous whether in sunshine or shade; but the whole lustre of the illumined parts is attained by bright isolated touches of reflected light.

The works of Turner will supply us with still more striking examples, especially in cases where slanting sunbeams are cast from a low sun along breakers, when the shadows will be found in a state of perpetual transition, now defined for an instant on a mass of foam, then lost in an interval of smooth water, then coming through the body of a transparent wave, then passing off into the air upon the dust of the spray—supplying, as they do in nature, exhaustless combinations of ethereal beauty. From Turner’s habit of choosing for his subjects sea much broken with foam, the shadows in his works are more conspicuous than in Stanfield’s, and may be studied to greater advantage. To the works of these great painters, those of Vandevelde may be opposed for instances of the impossible. The black shadows of this latter painter’s near waves supply us with innumerable and most illustrative examples of everything which sea shadows are not.

Finally, let me recommend your correspondent, if he wishes to obtain perfect knowledge of the effects of shadow on water, whether calm or agitated, to go through a systematic examination of the works of Turner. He will find every phenomenon of this kind noted in them with the most exquisite fidelity. The Alnwick Castle, with the shadow of the bridge cast on the dull surface of the moat, and mixing with the reflection, is the most finished piece of water-painting with which I am acquainted. Some of the recent Venices have afforded exquisite instances of the change of color in water caused by shadow, the illumined water being transparent and green, while in the shade it loses its own color, and takes the blue of the sky.

But I have already, Sir, occupied far too many of your valuable pages, and I must close the subject, although hundreds of points occur to me which I have not yet illustrated192. The discussion respecting the Grotto of Capri is somewhat irrelevant, and I will not enter upon it, as thousands of laws respecting light and color are there brought into play, in addition to the water’s incapability of shadow.193 But it is somewhat singular that the Newtonian principle, which your correspondent enunciates in conclusion, is the very cause of the incapability of shadow which he disputes. I am not, however, writing a treatise on optics, and therefore can at present do no more than simply explain what the Newtonian law actually signifies, since, by your correspondent’s enunciation of it, “pellucid substances reflect light only from their surfaces,” an inexperienced reader might be led to conclude that opaque bodies reflected light from something else than their surfaces.

The law is, that whatever number of rays escape reflection at the surface of water, pass through its body without further reflection, being therein weakened, but not reflected; but that, where they pass out of the water again, as, for instance, if there be air-bubbles at the bottom, giving an under-surface to the water, there a number of rays are reflected from that under-surface, and do not pass out of the water, but return to the eye; thus causing the bright luminosity of the under bubbles. Thus water reflects from both its surfaces—it reflects it when passing out as well as when entering; but it reflects none whatever from its own interior mass. If it did, it would be capable of shadow.

I have the honor to be, Sir,Your most obedient servant,The Author of “Modern Painters.”[From “The London Review,” May 16, 1861.]

THE REFLECTION OF RAINBOWS IN WATER. 194

To the Editor of “The London Review.”

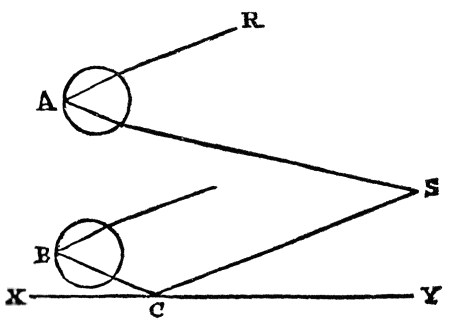

Sir: I do not think there is much difficulty in the rainbow business. We cannot see the reflection of the same rainbow which we behold in the sky, but we see the reflection of another invisible one within it. Suppose A and B, Fig. 1, are two falling raindrops, and the spectator is at S, and X Y is the water surface. If R A S be a sun ray giving, we will say, the red ray in the visible rainbow, the ray, B C S, will give the same red ray, reflected from the water at C.

FIG. 1.

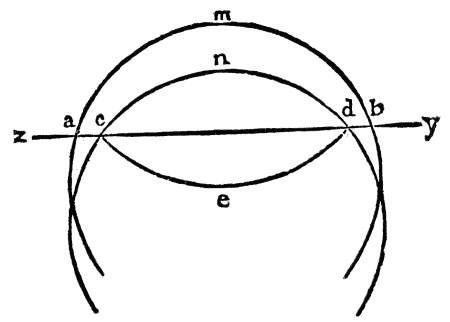

It is rather a long business to examine the lateral angles, and I have not time to do it; but I presume the result would be, that if a m b, Fig. 2, be the visible rainbow, and X Y the water horizon, the reflection will be the dotted line c e d, reflecting, that is to say, the invisible bow, c n d; thus, the terminations of the arcs of the visible and reflected bows do not coincide.

FIG. 2.

The interval, m n, depends on the position of the spectator with respect to the water surface. The thing can hardly ever be seen in nature, for if there be rain enough to carry the bow to the water surface, that surface will be ruffled by the drops, and incapable of reflection.

Whenever I have seen a rainbow over water (sea, mostly), it has stood on it reflectionless; but interrupted conditions of rain might be imagined which would present reflection on near surfaces.

Always very truly yours,J. Ruskin.7th May, 1861.

[From “The Proceedings of the Ashmolean Society,” May 10, 1841.]

A LANDSLIP NEAR GIAGNANO

“The Secretary read a letter195 from J. Ruskin, Esq., of Christ Church, dated Naples, February 7, 1841, and addressed to Dr. Buckland,196 giving a description of recent landslip near that place, which had occasioned a great loss of life: it occurred at the village of Giagnano, near Castel-a-mare, on the 22d of January last. The village is situated on the slope of a conical hill of limestone, not less than 1400 feet in height, and composed of thin beds similar to those which form the greater part of the range of Sorrento. The hill in question is nearly isolated, though forming part of the range, the slope of its sides uniform, and inclined at not less than 40°. Assisted by projecting ledges of the beds of rock, a soil has accumulated on this slope three or four feet in depth, rendering it quite smooth and uniform. The higher parts are covered in many places with brushwood, the lower with vines trellised over old mulberry trees. There are slight evidences of recent aqueous action on the sides of the hill, a few gullies descending towards the east side of the village. After two days of heavy rain, on the evening of January 22, a torrent of water burst down on the village to the west of these gullies, and the soil accumulated on the side of the hill gave way in a wedge-shaped mass, the highest point being about 600 feet above the houses, and slid down, leaving the rocks perfectly bare. It buried the nearest group of cottages, and remained heaped up in longitudinal layers above them, whilst the water ran in torrents over the edge towards the plain, sweeping away many more houses in its course. To the westward of this point another slip took place of smaller dimensions than the first, but coming on a more crowded part of the village, overwhelmed it completely, occasioning the loss of 116 lives.”

[From “The Athenæum,” February 14, 1857.]

THE GENTIAN. 197

Denmark Hill, Feb. 10.

If your correspondent “Y. L. Y.” will take a little trouble in inquiring into the history of the gentian, he will find that, as is the case with most other flowers, there are many species of it. He knows the dark blue gentian (Gentiana acaulis) because it grows, under proper cultivation, as healthily in England as on the Alps. And he has not seen the pale blue gentian (Gentiana verna) shaped like a star, and of the color of the sky, because that flower grows unwillingly, if at all, except on its native rocks. I consider it, therefore, as specially characteristic of Alpine scenery, while its beauty, to my mind, far exceeds that of the darker species.

I have, etc.,J. Ruskin.[Date and place of original publication unknown.]

ON THE STUDY OF NATURAL HISTORY

To Adam White, of Edinburgh.

It would be pleasing alike to my personal vanity and to the instinct of making myself serviceable, which I will fearlessly say is as strong in me as vanity, if I could think that any letter of mine would be helpful to you in the recommendation of the study of natural history, as one of the best elements of early as of late education. I believe there is no child so dull or so indolent but it may be roused to wholesome exertion by putting some practical and personal work on natural history within its range of daily occupation; and, once aroused, few pleasures are so innocent, and none so constant. I have often been unable, through sickness or anxiety, to follow my own art work, but I have never found natural history fail me, either as a delight or a medicine. But for children it must be curtly and wisely taught. We must show them things, not tell them names. A deal chest of drawers is worth many books to them, and a well-guided country walk worth a hundred lectures.

I heartily wish you, not only for your sake, but for that of the young thistle buds of Edinburgh, success in promulgating your views and putting them in practice.

Always believe me faithfully yours,J. Ruskin.END OF VOLUME 11

“The Bibliography of Ruskin: a bibliographical list, arranged in chronological order, of the published writings of John Ruskin, M.A. (From 1834 to 1879.)” By Richard Herne Shepherd.

2

The letter out of which it took its rise, however, will be found on the 82d page of the first volume; and with regard to it, and especially to the mention of Mr. Frith’s picture in it, reference should be made to part of a further letter in the Art Journal of this month.

“I owe some apology, by the way, to Mr. Frith, for the way I spoke of his picture in my letter to the Leicester committee, not intended for publication, though I never write what I would not allow to be published, and was glad that they asked leave to print it.” (Art Journal, August, 1880, where this sentence is further explained.)

3

Some of the notes, it will be remarked, are in larger type than the rest; these are Mr. Ruskin’s original notes to the letters as first published, and are in fact part of them; and they are so printed to distinguish them from the other notes, for which I am responsible.

4

It should be 16th, the criticism having appeared in the preceding weekly issue.

5

See “Modern Painters,” vol. i. p. 159 (Pt. II. § 2, cap. 2, § 5). “Again, take any important group of trees, I do not care whose,—Claude’s, Salvator’s, or Poussin’s,—with lateral light (that in the Marriage of Isaac and Rebecca, or Gaspar’s Sacrifice of Isaac, for instance); can it be supposed that those murky browns and melancholy greens are representative of the tints of leaves under full noonday sun?” The picture in question is, it need hardly be said, in the National Gallery (No. 31).

6

See “Modern Painters,” vol. i. pp. 157-8 (Pt. II. § ii., cap. 2, § 4). The critic of the Chronicle had written that the rocky mountains in this picture “are not sky-blue, neither are they near enough for detail of crag to be seen, neither are they in full light, but are quite as indistinct as they would be in nature, and just the color.” The picture is No. 84 in the National Gallery.

7

See “Modern Painters,” vol. i. p. 184 (Pt. II. § ii., cap. 4, § 6). “Turner introduced a new era in landscape art, by showing that the foreground might be sunk for the distance, and that it was possible to express immediate proximity to the spectator, without giving anything like completeness to the forms of the near objects. This, observe, is not done by slurred or soft lines (always the sign of vice in art), but by a decisive imperfection, a firm but partial assertion of form, which the eye feels indeed to be close home to it, and yet cannot rest upon, nor cling to, nor entirely understand, and from which it is driven away of necessity to those parts of distance on which it is intended to repose.” To this the critic of the Chronicle had objected, attempting to show that it would result in Nature being “represented with just half the quantity of light and color that she possesses.”

8

The passage in the Chronicle ran thus: “The Apollo is but an ideal of the human form; no figure ever moulded of flesh and blood was like it.” With the objection to this criticism we may compare “Modern Painters” (vol. i. p. 27), where the ideal is defined as “the utmost degree of beauty of which the species is capable.” See also vol. ii. p. 99: “The perfect idea of the form and condition in which all the properties of the species are fully developed is called the Ideal of the species;” and “That unfortunate distinctness between Idealism and Realism which leads most people to imagine that the Ideal is opposed to the Real, and therefore false.”

9

This picture of Sir David Wilkie’s was presented to the National Gallery (No. 99) by Sir George Beaumont, in 1826.

10

The bank of cloud in the “Sacrifice of Isaac” is spoken of in “Modern Painters” (vol. i. p. 227, Pt. II., § iii., cap. 3, §7), as “a ropy, tough-looking wreath.” On this the reviewer commented.

11

“We agree,” wrote the Chronicle, “with the writer in almost every word he says about this great artist; and we have no doubt that, when he is gone from among us, his memory will receive the honor due to his living genius.” See also the postscript to the first volume of “Modern Painters” (pp. 422-3), written in June, 1851.

12

Cimabue. The quarter of the town is yet named, from the rejoicing of that day, Borgo Allegri. [The picture thus honored was that of the Virgin, painted for the Church of Santa Maria Novella, where it now hangs in the Rucellai Chapel. “This work was an object of so much admiration to the people, … that it was carried in solemn procession, with the sound of trumpets and other festal demonstrations, from the house of Cimabue to the church, he himself being highly rewarded and honored for it. It is further reported, and may be read in certain records of old painters, that whilst Cimabue was painting this picture in a garden near the gate of San Pietro, King Charles the Elder, of Anjou, passed through Florence, and the authorities of the city, among other marks of respect, conducted him to see the picture of Cimabue. When this work was shown to the king, it had not before been seen by any one; wherefore all the men and women of Florence hastened in great crowds to admire it, making all possible demonstrations of delight. The inhabitants of the neighborhood, rejoicing in this occurrence, ever afterwards called that place Borgo Allegri; and this name it has since retained, although in process of time it became enclosed within the walls of the city.—Vasari, “Lives of Painters.” Bohn’s edition. London, 1850. Vol. i. p. 41. This well-known anecdote may also be found in Jameson’s “Early Italian Painters,” p. 12]. (Original note to the letter: see editor’s preface.)