Полная версия

The Jewelled Moth

They were all looking forward to the following Sunday, when they were being taken for an afternoon of tea and boating by the river. There would even be a boat race for staff teams, which the young salesmen, grooms and porters were taking very seriously indeed. Sophie knew that Billy’s uncle, Sid Parker, who was the Head Doorman, would be captaining one of the boats, and Joe would be rowing as one of his crew, whilst Billy himself was immensely proud to have been chosen as the cox, whose job it was to shout out instructions to the rowers. There was already much competition developing over which team was going to win.

‘Uncle Sid bet Monsieur Pascal five shillings that our team is going to take first prize,’ related Billy now, managing to stuff in a potted-meat sandwich at the same time.

‘Well I’m glad he’s feeling so confident,’ said Joe, ‘because I can tell you now, I’m not. It’s blooming hard work, this rowing lark.’

‘I just think it’s a fearful shame that girls aren’t allowed to take part in the boat race,’ said Lil. ‘Why should the men have all the glory? I can row just as well as anyone. What are we supposed to do, just stand about and watch ? Where’s the fun in that?’

Billy opened his mouth to share his views on girls taking part in boat races. ‘Er – what else will be happening at the fête, apart from the boating, I mean?’ Sophie interjected quickly.

‘There’s a super tea,’ Billy went on, taking obvious pleasure in being the one with all the inside information. ‘I saw the menu on Miss Atwood’s desk. Cold chicken. Salmon mayonnaise. Strawberries and cream, ices, ginger beer. And afterwards, there’s going to be a band and dancing.’

‘I heard about the dancing. The girls in Millinery and Ladies’ Fashions are awfully excited about it. Most of them are getting new frocks specially.’

‘I wish I could have a new frock. I’m jolly short of cash,’ said Lil, with a heavy sigh. She turned to Sophie: ‘I’ve had some rather rotten news. They’ve just announced that the show is going to end its run this week, so I’ll be out of a job.’

‘But why? It’s been a tremendous success, hasn’t it?’

‘Yes, it did ever so well – but silly old Kitty Shaw is leaving the stage to be married, and they’ve decided that the show can’t go on without her. It’s really an awful bother.’

‘Don’t worry,’ said Joe, loyally. ‘You’ll get another part in two shakes.’

‘That’s the bright spot,’ went on Lil, sounding more like her usual self. ‘I’ve found out that Mr Lloyd and Mr Mountville are going to be putting on a new show at the Grosvenor Theatre. It’s called The Inheritance and it’s all about high society. It sounds terribly elegant, and I’m determined to get a part – a real part, not just the chorus line. But the auditions aren’t until next month, so I’m going to be rather broke until then.’

‘Well, at least you’ve got Sinclair’s and the dress shows,’ said Sophie.

Lil made a face. ‘Ugh! Parading around in absurd gowns for all those stuck-up old ladies! But you’re right; it is better than nothing. At least it pays for my lodgings. But this is going to be my last tea out for a while. It’s plain bread and butter for me from now on,’ she said grimly, before hurriedly helping herself to another iced bun, as if she thought they might be about to vanish from the plate at any moment.

‘Haven’t you got any of your reward money left?’ asked Billy curiously.

Lil shrugged. ‘Not exactly. I mean, I have a little, but it won’t go far. I spent some of it on singing lessons, and dancing classes, and I thought I ought to get a new outfit for auditions, and then one of the other chorus girls was in rather a fix, so I said I’d lend her two pounds – and, well, it’s perfectly dreadful how easy it is to spend money when you have it,’ she finished up.

‘Couldn’t your mum and dad help you out till you get another part?’ asked Joe, wondering how anyone could possibly spend such a vast sum as twenty-five pounds in just a few short months. He knew that although they were not as grand as some of the rich society ladies and gentlemen who came into Sinclair’s department store, Lil’s family were still well-to-do.

‘I won’t ask them,’ said Lil, a very stubborn expression on her face. ‘I’m determined to prove that I can stand on my own two feet. If I give them half a chance, Mother will have me back at home embroidering idiotic fire-screens, and entertaining eligible young men to tea.’

Lil’s tone made this sound like such a ghastly proposition that Sophie couldn’t help laughing, although the truth was that sometimes she felt a little envious of her friend’s family. She wondered what it would be like to have a mother worrying about you: she could scarcely even remember her own Mama, who had died when she was very small.

‘Oh, I almost forgot!’ she exclaimed, all at once remembering the unopened envelope in her pocket. She produced it now and handed it to Lil. ‘Look at this. It came earlier.’

‘I say, how strange! Could it be something for your birthday?’

‘That’s what I thought at first, but it has both our names on it,’ said Sophie, pointing.

Lil looked intrigued. ‘Let’s find out,’ she said, tearing it open at once.

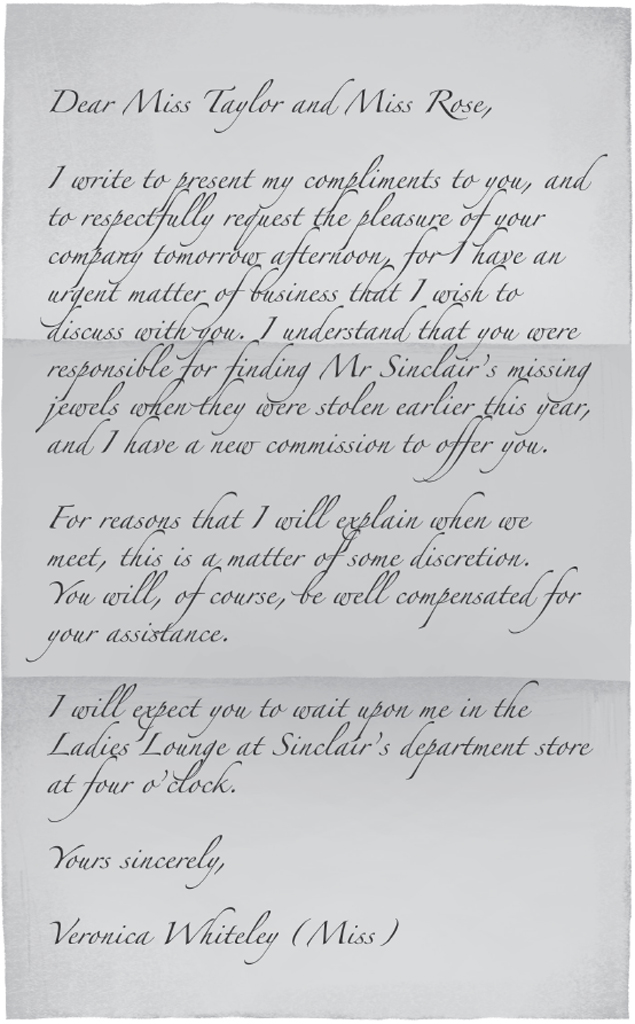

But once she had taken out the letter and put it on the table in front of them between the teacups and the sandwiches, they were as perplexed as ever. On what was clearly expensive writing paper, there were a few short lines:

‘Well, what does it say?’ asked Joe, looking at the others expectantly. Growing up on the streets of the East End, he had never learned to read.

‘She wants to hire us!’ exclaimed Lil excitedly. ‘As detectives !’

Billy reached across the table and took hold of the note for a closer look. ‘But why would she want to do that?’ he demanded, frowning.

‘It says right there, in black and white,’ said Lil. ‘She heard about how we found the clockwork sparrow!’

‘Well I’ll be blowed,’ said Joe. ‘That’s a turn-up for the books!’

‘But why just you and Sophie?’ asked Billy. ‘I mean, you’re –’ and here he broke off suddenly, his cheeks turning rather pink.

‘Girls? ’ demanded Lil, at once. ‘Girls can be detectives just as well as boys can,’ she burst out indignantly. ‘Girls are just as brave and clever as boys, you know! I realise they aren’t in those silly detective stories of yours – all the girls in those are perfect idiots who do nothing but swoon all over the place – but that’s a lot of old rot.’

Billy looked rather indignant, and opened his mouth as if he was about to argue, but Joe was frowning. ‘It’s a bit of a rum do, though, isn’t it? I mean, why not go to a professional – a private detective? Or the coppers, come to that?’

Sophie frowned. After what had happened in the spring, the last thing she wanted to do was get in any more trouble with the police. ‘Do you think there’s something fishy about it? Perhaps we oughtn’t to meet her?’

‘Of course we should meet her,’ exclaimed Lil. ‘Goodness, don’t be such a lot of stick-in-the-muds. Here I am, at a loose end and desperate to earn a bit of money – and then along comes this letter! It’s absolutely perfect.’

‘But we have no idea what she wants us to do,’ said Sophie. ‘And we aren’t really detectives. How do we know we’ll even be able to help?’

‘We managed to find Mr Sinclair’s missing jewels, didn’t we?’ replied Lil at once. ‘Have you forgotten what Mr McDermott said to us?’

Sophie had not forgotten. The truth was that she had thought of his words very often during the duller moments in the Millinery Department. ‘You have first-rate instincts, Miss Taylor – and with Miss Rose here to help you act on them, I suspect you would make rather a formidable team. If you ever find yourselves tired of Sinclair’s, come and find me. I think there could be quite a different sort of career out there for a couple of young ladies like you. ’ Remembering them now gave her a sudden prickle of pride.

‘Anyway, the absolute worst that could happen is that we go along and aren’t too keen on what she has to say. Then we can just say no to this job – or what does she call it? – commission,’ went on Lil stoutly.

‘Well . . . I suppose there couldn’t be any harm in at least going to talk to her,’ said Sophie. In spite of her caution, she felt a pleasing buzz of excitement.

Across the table, Billy’s face was screwed into a peculiar mixture of eagerness and indignation. Sophie realised that he was just as enthusiastic as Lil, but still rather resentful that he had not been included in the invitation. Joe was watching with a look of quiet amusement on his face, and now he grinned at Sophie as if he knew exactly what she was thinking.

‘Of course, we’ll need both of you to help too,’ said Sophie.

A look of relief crossed Billy’s face. ‘Well, it’s a bit busy at the moment,’ he said in a deliberately casual tone. ‘You know, working for the Captain and the evening classes, and practising for the boat race and everything. But I expect I’ll probably be able to help out.’

Lil looked eagerly at Joe. ‘Course I’ll help, if I can,’ he said, with a smile and a shrug.

‘Hurrah!’ said Lil. ‘That’s settled then!’

‘Lil and I will go and see this Miss Whiteley tomorrow,’ said Sophie with a decisive nod. ‘Then let’s meet again after the store closes, and we can tell you all about it.’

CHAPTER FOUR

Song was angry. ‘What on earth were you thinking?’ he demanded.

‘That’s no way to talk to your father!’ snapped out Mum. ‘I’ll thank you to take a more civil tone!’

‘But they might have killed you!’

Dad gave a little snort. ‘It would take more than that gang of brainless thugs to finish me off,’ he muttered.

Mei stared at him anxiously across the table. She hated to see him so white and tired-looking. The bruises on his face were a constant reminder of the moment she had found him, crumpled on the ground – she had been quite sure that he was dead.

Song looked at their father for a long moment, then sighed and sat back in his chair, his hands bunched into fists in front of him. ‘All I’m saying is that you can’t just refuse to pay the Baron’s Boys,’ he said in his usual quiet voice. ‘That isn’t how things work.’

‘It’s a matter of principle,’ said Mum, rather stiffly. ‘People round here look to us to set an example, Song, you know that. We all work hard. We’ve all got precious little as it is. We can’t let them turn up here and demand our money. It’s nothing more than bullying. If we all stand up to them, maybe we can put a stop to it.’

Song made a noise of frustration in the back of his throat. ‘But you can’t stand up to them, Mum. That would be like . . . one mouse against a hundred cats! Besides, no one else is going to put themselves in danger, especially when they see what happened to Dad. People are afraid .’

There was a long pause. Then Dad spoke. ‘Song is right . . .’ he said slowly. His voice was heavy. ‘We can’t stand against the Baron, Lou. He runs the East End. Everyone knows that. We should be grateful it’s taken him this long to reach into China Town.’

Mei felt a slow chill creep over her. She knew about the Baron, of course: everyone in Limehouse did. He was the villain of every whispered tale – the monster who was ‘coming to get you’ in all the children’s games. No one had ever seen him, but almost everyone claimed to know someone who’d caught a glimpse, just once, and come to a bad end. To see the Baron himself would be the worst of all bad omens – worse than a black cat crossing your path, worse than breaking a looking glass. There were dozens of stories about him. Some people said that he was a bloodthirsty murderer who had left a trail of horribly dismembered victims all across the East End. Others said he had once been an ordinary man, until he had sold his soul to the devil. Either way, everyone was afraid of him. To Mei, he was the dark shadows underneath the bed, the creaking floorboards, the distant shriek in the night.

But the Baron was much more than just a fairy tale, a bogeyman from a child’s nightmare. He was the top man in the East End and everyone knew it. His net stretched from Spitalfields to Bow. The Port of London Authority might think that it ran the docks, but the folk of the East End knew better. They knew that the Baron had eyes on every load that came in or out of every ship that docked. They knew that he did his own business there too, and they carefully looked the other way when ships slipped in and out under the Baron’s protection. No one would dare to cross him.

As for the Baron’s Boys, they were almost as feared as the Baron himself. They were the ever-growing gang of toughs who did the Baron’s business – legitimate or otherwise. They collected his rents – the protection money he demanded from most of the East End – and dealt with those who got in their way. People hurried in the opposite direction if they saw them standing on a street corner. Conversation fell away when a group of them swaggered up to the bar of the Star Inn, demanding the landlord’s best beer, or when one or two came striding into the fish shop for their penny bit and ha’p’orth of chips. And now they had been here, to Lim’s shop.

Mei felt sick. The back room had always seemed like the safest place in the world when the family were sitting around the table, in the warmth of the range. But suddenly it was just a room, any room, small and cold. All the laughter had gone out of it. The green parrot in the corner was silent, and even the twins sat still and quiet, their eyes round as saucers.

As if it was their silence that had suddenly reminded her that they were there, Mum glanced over at the twins. ‘Boys, go outside,’ she said curtly. ‘Run along now, chop-chop.’

Dad shook his head weakly. ‘No, Lou. I don’t want them out there. It’s too dangerous,’ he said.

‘Upstairs then,’ said Mum firmly.

‘But, Dad – we’ve got to go out.’ Jian spoke up, looking alarmed and astonished. ‘We’re s’posed to meet Spud and Ginger for a kick-about after tea. They’ll be waiting for us!’

‘Well they’ll be waiting a long time, then, won’t they?’ snapped Mum. ‘You heard your father. You’re not to go out. So upstairs you go. And Mei, you can get started on clearing things up in the shop.’

They wanted them out of the way so they could talk, Mei knew. There was no sense in arguing. She got up, and obediently shepherded the boys out of the back room and up the crooked stairs towards the bedroom. The twins had forgotten about the Baron’s Boys already. They were babbling away in the funny mixture of playground slang and their own peculiar twin language that they used when they were speaking to each other. Now, they seemed to be jabbering something about a game of cowboys and Indians.

‘Come and play with us, Mei,’ said Jian. ‘We’ll let you be the squaw.’

‘We’ll make Song’s bed into our fort,’ said Shen with a grin.

But Mei shook her head. Normally she’d have been happy to have the excuse to join in with one of the twins’ make-believe games, but today, she couldn’t think about anything beyond Dad’s bruised face and the Baron’s Boys.

Instead, as they bounded up the stairs, she went slowly through into the deserted shop as Mum had told her. It looked quite sad and unlike its usual self. The door was locked and bolted, and Song had nailed boards over the broken windows so that only one or two beams of light broke through. Dust motes danced in the shafts of light.

She decided to light a lamp to try and break through the gloom, but the glow it cast out seemed somehow feeble. She looked around her, feeling despondent. There was so much to do that she hardly knew where to begin. Listlessly, she took up the broom and began to sweep the floor, making a little mound of spilt tea and tobacco and broken glass.

She could hear more voices now, in the back room. It sounded like Ah Wei, Song’s boss at the Eating House, and Mr and Mrs O’Leary from the baker’s, and Mrs Wu from the Magic Lantern Show. Their voices sounded solemn and grave. Traces of their conversation reached her as she swept: ‘. . . can’t go on like this ’, ‘. . . that sort of money ’, ‘. . . making an example ’, ‘. . . far too dangerous ’.

She didn’t want to hear them. To block them out, she began to tell one of Granddad’s stories to herself, an old tale about a talking fox, but she could not concentrate. She was getting it all wrong. The story of the fox kept getting mixed up with the cobbler’s warning, with Dad lying crumpled on the floor, and then with Granddad himself. Thinking of Granddad made her want to cry, and that would not do – Song would say she was being a cry baby. He said she needed to grow up now she had left school: she was too old to be a feather-brain; she shouldn’t spend so much time playing with the twins; she oughtn’t to always have her nose buried in a book.

Once, she and Song had been the best of friends. They had done everything together; told each other all their secrets; but things had changed. He seemed so much older, all of a sudden. She could hear him now in the back room, his voice forceful and authoritative, although she couldn’t make out what he was saying. When had he become one of the grown-ups?

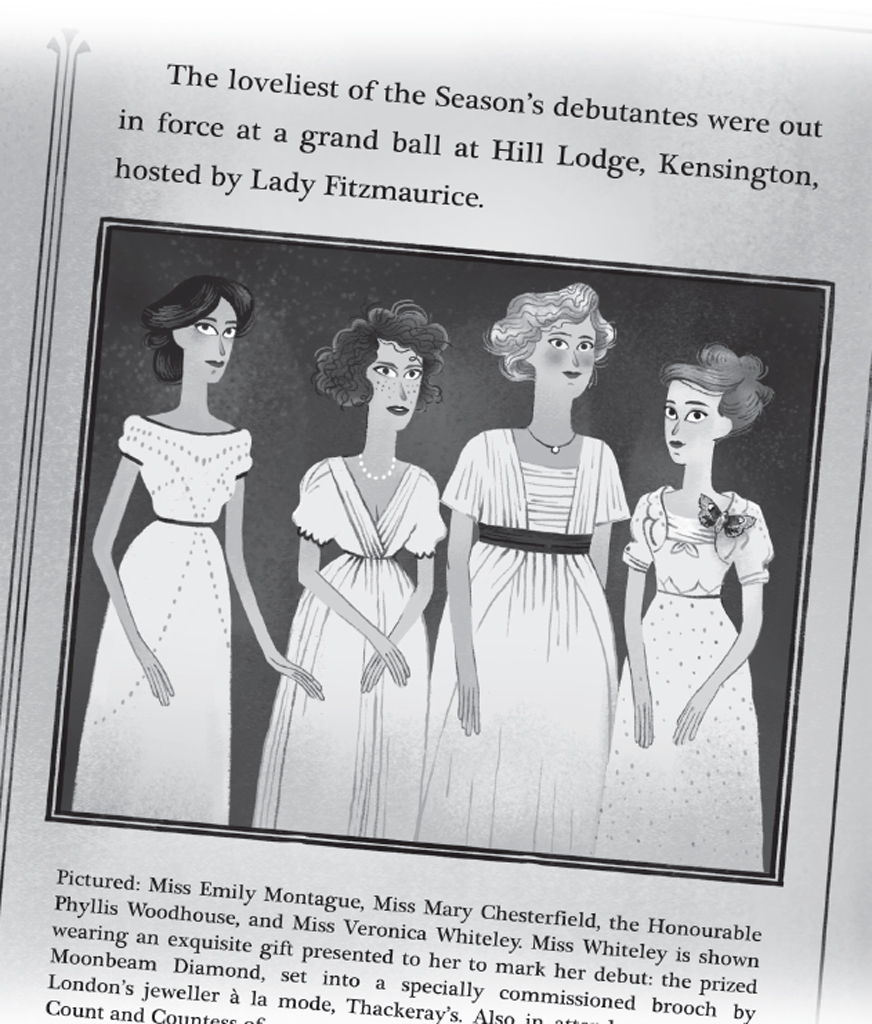

Then someone in the back room made an unhappy gasping sort of sound – a strangled sob. It wasn’t Mum or Dad or Song, but all the same it pulled her up short. She even stopped pretending to sweep. Instead, she sat down on the stool behind the counter, and wedged her hands over her ears. There was a copy of yesterday’s newspaper lying nearby, and she pulled it towards her and opened it, hoping for a new episode of the serial story to distract herself with. She turned the pages rapidly over a report of a murder in Whitechapel, and a robbery in Shoreditch, but there was no story today, so instead she fixed her attention upon the society pages. She liked to look at them, sometimes, intrigued by the pictures of young ladies in white dresses with elegant-sounding names like Lady Cynthia Delaney or Miss Louisa Hampton-Lacey . The fancy descriptions of grand balls and elegant gowns could have so easily come from one of her favourite fairy tales.

Now, she read them with grim determination, taking in every word of an account of a charity fashion show at a West End store; a report on the upcoming marriage of a glamorous actress; and an article about a lavish society ball. The voices rose and fell in the back room, but Mei read on, filling her mind with words like opera and bazaar and waltz .

Then she stopped short. Two words jumped out at her from the page, and all at once, it was as if the sounds in the next room had vanished into abrupt and ominous silence. She saw and heard nothing: all that was left were those two words, printed in smudgy black ink, in the middle of a paragraph: Moonbeam Diamond.

CHAPTER FIVE

The Ladies’ Lounge at Sinclair’s was a most elegant place. Arrayed like a fashionable drawing room, it was decorated entirely in white and gold, with bowls of flowers set here and there, and plenty of soft chairs and comfortable sofas. It was no wonder it had become a favourite destination for London’s society ladies to meet after a busy day of shopping. That afternoon, the room was full of them: ladies drinking iced lemonade in tall glasses served to them by maids in frilled white aprons; ladies talking vigorously in lively groups; ladies sitting alone, studiously reading the newspaper. There was a low buzz of civilised conversation in the air, and the delicate chink of china and silverware. As Sophie and Lil entered the room, they could not help feeling a little awkward, unsure of exactly who they were looking for, or what they ought to do.

But almost at once, one of the maids came up to them, and directed them to a corner over by the window. Glancing at each other apprehensively, they hurried over. Sophie was not quite sure who she had expected to find, but it certainly was not the young lady who sat waiting, small but very upright, in a large velvet armchair, coolly drinking a cup of tea.

‘You are Miss Taylor and Miss Rose, I suppose,’ she said in a high, rather petulant voice, looking them up and down critically.

‘Yes, I’m Sophie Taylor. How do you do?’ said Sophie, holding out a hand. The young lady looked at it uncertainly for a moment, then gingerly took it in her own lace-gloved fingers.

‘And I’m Lilian Rose,’ said Lil, seizing the young lady’s hand in her turn and giving it such a hearty shake that she looked alarmed and pulled her hand hurriedly away.

‘My name is Veronica Whiteley. I am pleased to meet you,’ said the young lady, with a haughty nod. Sophie looked at her in surprise. The tone of her letter had conjured up a vision of an elderly spinster, but this girl was young – really, she couldn’t have been much older than Lil – and she was dressed very beautifully in a much ruffled, lace-trimmed ivory gown. She must be one of this season’s debutantes, and a particularly wealthy one at that. What was more, Sophie realised that she knew her. She was one of the three young ladies who had been in the Millinery Department the previous day – the one who had tried on the Paris hat.

But Miss Whiteley gave no indication that she recognised Sophie. ‘Do sit down,’ she said, giving a queenly waft of her hand towards the two hard chairs placed opposite her. As they took their seats, Sophie watched the young lady with interest. Although her clothes were expensive and beautifully made, Sophie couldn’t help thinking that they didn’t suit her very well. She was pretty, with china-white skin, a small pink mouth and carefully waved red-gold hair. But all the frills and flounces made her look rather like one of the expensive porcelain dolls that were on sale in the store’s Toy Department. Yet there was nothing at all doll-like about her expression: she was looking at them both with eyes like gimlets, a frown creasing up her white forehead as she sipped tea from a bone-china cup.

‘How can we help you?’ Sophie asked curiously.

‘I have been told that you were responsible for finding Mr Sinclair’s stolen jewels,’ Miss Whiteley began, assuming a very formal manner. Lil opened her mouth to say something, but Miss Whiteley was evidently not expecting there to be any interruptions, and swept onwards. ‘I contacted you because I wished to discuss a similar commission. It is of a highly confidential nature – I trust I can be assured of your complete discretion.’

They said she could, and she went on:

‘I was recently given a gift by a gentleman. It’s one of a kind and extremely valuable – a jewelled brooch in the shape of a moth, made especially for me. Last week it went missing, and I would like you to undertake to find it.’

Veronica found that her hand was shaking slightly as she replaced her teacup in its saucer. She had borrowed her haughty manner from the Dowager Countess of Alconborough, always so imperious in her black velvet and jet beads, assuming complete control of any conversation. Today, she wanted to be no less impressive. It was imperative that these girls took her seriously: she would not be dismissed as just another idiotic debutante.

Although, looking at them again, her lips pursed. She had not expected them to be so very young . Why, the smaller one looked even younger than she was herself ! She had expected them to be older: sophisticated and perhaps a little daring, women of the world, like the heroines of the rather scandalous novels she borrowed from Isabel, her stepmother, on the sly. These two looked more like a pair of schoolgirls than young lady detectives! But it was too late: she had already told them about the jewelled moth, and she would simply have to go on with it now.

It was quite a ridiculous position to find herself in, she thought crossly. If only she were an adult, she would have been able to hire a real detective to find the missing brooch for her. But being a debutante meant that every moment of the day was supervised, from the moment that her maid woke her in the morning, to the moment she went to bed at night after yet another ball or reception. Father and Isabel treated her as if she were a baby. She’d had far more freedom back in the schoolroom with her governess! Now, she was chaperoned every minute of the day, and there was no chance whatsoever that they would ever let her go off alone to a secret appointment with a private detective.