Полная версия

Daughter Of The Burning City

“I don’t know what you two did,” he says, “but Gomorrah’s in enough trouble here as it is. If rumors spread beyond Frice that we’ve been stealing from patrons, then the other Up-Mountain cities will revoke their invitations to come. Not to mention all this chaos.”

He acts as if Jiafu and I are the only thieves in this whole festival of debauchery. To the visitors, the chance of pickpockets or magical mischief accounts for half the thrill of Gomorrah.

“It was a small job. Count Pomp-di-pomp is supposed to be a bit dim, anyway. He’ll probably think he lost his ring himself.”

Gill rolls his eyes. “It’s Count Pompdidorra. He’s a very influential man.”

“Whatever.”

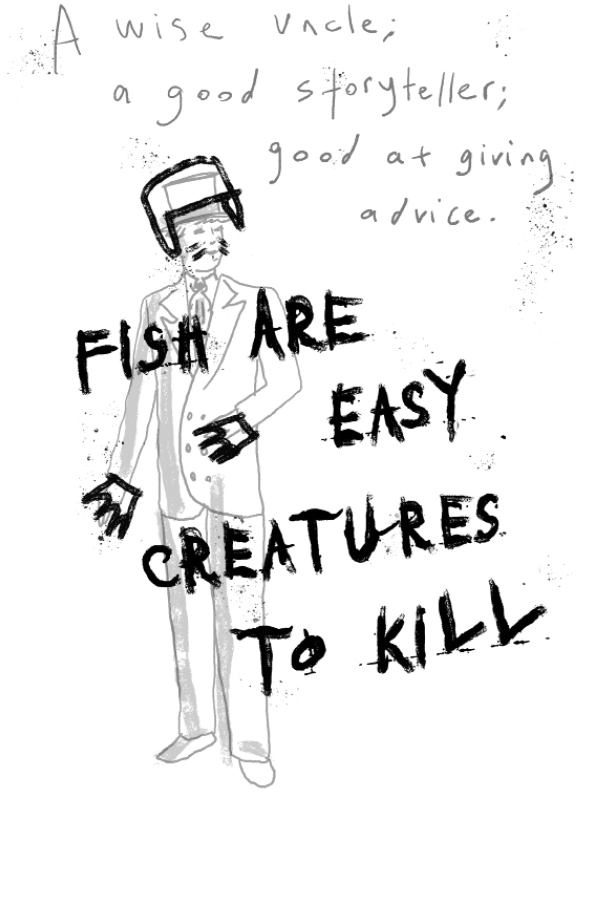

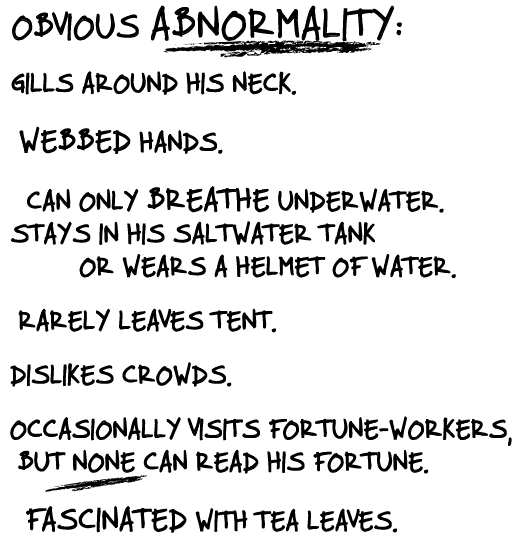

“Sorina,” he says, sighing. Most of Gill’s sentences are followed by a sigh. At least half of those are aimed at me. When I created Gill, I had “loving uncle” in mind, but, instead, he’s more of a nuisance. Though maybe that’s a bit harsh. It’s not that I don’t love Gill. Not that he doesn’t love me and all of us. But he’s certainly grumpier than in my original blueprints. If we wanted to live by all his rules, we’d go live in a religion-crazed Up-Mountain city. The only person who listens to Gill is

Nicoleta, who is essentially his henchman, repeating his advice or scolding someone whenever Gill isn’t present to do so himself.

“To be frank—” Gill is always frank “—you’re jeopardizing the already grim reputation of the entire Festival. And if people keep losing valuable possessions during our show, no one’s going to buy tickets.”

I’m done with this conversation. Unless Gill can concoct a new idea for me to earn some coin for Kahina, then I’ll stick with Jiafu. I’m not really hurting anyone. The patrons we select are too rich to notice a missing necklace here, a missing watch there.

“It’s my show,” I say.

“If it’s all your show, you can do tricks in this tank next time. Or fit into Venera’s two-by-two-foot box,” he snaps. “Don’t be a child.”

“Technically, I’m older than you,” I say. I created Gill when I was nine, which only makes him seven years old.

He sighs. “Of course, Sorina, you always have the last word.”

This particular statement infuriates me more than anything else. I’m sorry I worried him, but Kahina is more important than the slim risk involved. And I don’t understand how I could possibly be damaging the Festival’s reputation when people are always whispering about assassins and drug dealers in the Downhill. Petty theft is nothing compared to that.

I turn, my cloak swishing behind me, and stomp inside.

The others sit around our foldout table, huddled together on floor cushions. By the untouched game of lucky coins and the way they fidget, I can tell they’ve been worried.

I toss the forty-five coins on the table, which spill out of their pouch with clatters and clangs. Venera grimly gathers them up to add to our family-stash jar. “Got them no problem,” I say, knowing that I sound like an ass.

“It’s almost midnight,” Nicoleta says. “You took a long time.”

“Is it?” Jiafu and I usually meet at midnight after jobs, but I didn’t notice him waiting for me outside. I hate to leave them again, if only for a moment, but I need to talk to Jiafu.

“We can play lucky coins, now that we’re all here,” Unu says. He holds up the Beheaded Dame coin—the jewel of his collection—to glint in the lantern light.

“I’m not ready to lose again just yet,” I say. “I’m going to keep watch and make sure no officials come near the tent. I’ll be—”

“You shouldn’t go outside,” Nicoleta says, sighing. If one more person sighs at me, I’ll tear my hair out. The bald girl who sees without eyes. What a sight.

“—just out back,” I finish, waving and slipping out before any of them can stop me. There’s less commotion in our neighborhood than near the Menagerie and Skull Gate. Plus, I have my illusions to obscure me. I’m not worried.

The night air is sticky, yet refreshing compared to the tension with the others inside. Thankfully, Gill has disappeared—skulked back to his tent, where he’ll probably keep to himself the rest of the night, reading another one of his boring novels, where nothing exciting or romantic ever happens, and the reader always learns some righteous lesson in the end.

Lightning bugs blink within clouds of gnats, circling my face. The smoke that envelops Gomorrah utterly blocks out any view of the sky. The smoke is part of Gomorrah’s legend: once upon a time, we were burned to the ground. But we did not die. Instead we kept burning, kept moving, kept growing. The smoke surrounds us, even if we no longer burn. There is no fire, but sometimes, if you catch yourself around Gomorrah’s edges, the air thickens from stifling heat and the lanterns glow a little bit brighter. It reminds me of walking into the city’s memory—a very ancient memory.

This section of Gomorrah is lit by white torchlights and paper lanterns, which wear golden halos in the gray fog. Everyone in the Festival seems like a silhouette, a shadow of an actual person. It makes it easy to get lost and, depending where you are in Gomorrah, never be found again.

I scan the area beside my tent—a small clearing that serves as the back of two other tents, which house a family of fortune-workers and a silk salesman. Jiafu is nowhere. We usually meet outside after jobs, so why isn’t he here? If he’s skipping out on me, I swear, he’ll wake up tomorrow thinking there are dung beetles crawling out of his nostrils. I have a hard time believing Jiafu, the master of all crooks, would be scared of a few officials.

I sit on the grass, facing toward the thousands of tents that make up the Gomorrah Festival, the tallest being the Menagerie at the center. The family-friendly attractions—if you could call anything at Gomorrah family-friendly—are closest to the entrance, like games, circuses and my freak show. The majority of the Festival is in the back—private tents for prettymen and prettywomen, bars and gambling. We call that area the Downhill. Of the thousands of people who live in Gomorrah, I know the fewest from there.

Jiafu has five minutes before I get angry.

To the left, something catches my eye. A golden centipede wriggles down a tent post, and I suck in my breath and examine it. It’s the size of my pinky but twice as wide, with beady black eyes and soft fuzz. I gently pick it up and let it tickle my palm with its hundred feet.

I don’t remember when my bug collection began. I have over three hundred insects, gathered from various regions where the Festival has taken me, both in the Up-Mountains and Down-Mountains. A charm-worker down the way preserves them for me in glass vials, which I keep for decoration in my room—both for the aesthetics and to ensure that Nicoleta rarely comes in to nag me. Occasionally Villiam will gift me a book of local insects so I can learn about the ones in my collection. I like to consider myself an expert on all creepy crawlies. Probably because they make other people uncomfortable, but I see just how unique and fascinating they are. Highly underrated creatures. The bugs and I have this in common.

A horn blares across Gomorrah. Followed by screams.

“What the hell is that?” I wonder aloud. The centipede crawls up my wrist and arm, unperturbed. It sounded like a city horn from Frice. Maybe the officials are leaving.

I tiptoe around our three tents—the two where we sleep, and the Freak Show’s tent—wishing I wasn’t alone, in case I do need to face an official. Wishing we, like most of Gomorrah’s residents, lived near the Festival’s perimeter, not along a main path.

Across from the Freak Show tent lives another fortune-worker, and she—always determined to be the first on Gomorrah’s lengthy grapevine—slips out down the path to investigate the commotion approaching our neighborhood. I creep near one of the torch poles to be closer to the light.

An official on horseback trots down our path. By the way he scans the area, he’s looking for something or someone. Perhaps he’s rounding up the Frician citizens and marching them back to their city. The noise covered his approach, so I haven’t had time to prepare an illusion. I’m exposed.

The official stares at me, his face contorted in disgust. The centipede drops from my arm into the grass, but I don’t dare move to search for it. After a few tense moments, the official passes. I let out a sigh of relief.

I head back inside my tent, thinking I’ll just cut through the stage area to the back. It’s safer to be out of sight. And clearly Jiafu isn’t coming.

The show tent is empty, all the audience chairs vacant and the ground littered with kettle-corn kernels. I squint in the darkness. There’s something on the stage, but I can’t tell what it is.

“Hello?” I say, in case it’s a person. No one answers.

I creep closer to the stage and then climb up the steps. Something cracks under my sandal. The floor glistens. I’m standing in a mess of water and glass.

A figure lies on the floor, unmoving and limp. My eyes slowly adjust, so I can tell it’s a man lying facedown. He lies on a bed of broken glass and a puddle of water in the dead center of the stage.

I scream and then root around my pockets for a match, my hands trembling. I find one, strike it and bend down to the man’s body, bracing myself for my worst suspicions to be confirmed. I instantly recognize his dark hair, the grooves on both sides of his neck and his webbed hands.

It’s Gill.

I scream his name and then drop to the floor and roll him over. The back of his shirt is covered in blood. I shake him a few times, but he never responds. I rest his head on my lap, and blood dribbles from his mouth down his chin. “Gill. Gill,” I plead. I check his pulse, but find none.

None.

“No. No. No.” This is impossible. Gill can’t be dead. He’s my illusion. His body, though it feels solid, is only a figment of my imagination. No one can kill him, because he doesn’t truly exist.

Hesitantly, I lean him on his side and lift up his shirt, exposing the half dozen stab wounds across his back. They are a jagged, messy and oozing contrast to the smooth and translucent silver of his skin. My stomach wretches. I roll him onto his back once more and hug him closer.

I’m struck with a sudden inspiration; a flicker of hope. I can fix this. I can make him disappear. I can make him disappear and he’ll come back, just like before.

I grasp for my Strings and find Gill’s tethered among them. I gather them into a ball and toss them into his Trunk, a section of my mind I rarely visit except to make the illusions disappear. His Strings are lighter than usual, as if strands of hair rather than proper threads. Though the Trunk is open and full of Gill’s Strings, he doesn’t vanish from the stage as he should. I cry out in frustration. Why won’t he disappear?

His body remains in my arms, dead.

None of this makes sense.

I run my hands down his limp arm to his fingertips, to a shard of glass on the stage floor. The wheeled platform of the tank lies a few feet away. This glass couldn’t have broken by accident—it’s thick, made especially for Gill’s act during the show. Someone shattered it on purpose and then, afterward, stabbed him while he suffocated.

Someone, somehow, murdered him.

CHAPTER THREE

The dampness of the salt water and Gill’s blood seeps into my clothes. The sleeves of my robes. The knees of my thin pants. I tremble from the coldness against my skin, from the idea of kneeling in a pool of blood, from the image of Gill dying in this very spot. Of him gasping for oxygen, staring at the face of his killer, writhing on the stage floor among the broken glass, with no breath to call for help.

Gill’s body is heavy, pressing my kneecaps and ankle bones against the hard wood of the stage. All I register is what’s here. The slimy, sardine-like feeling of Gill’s corpse. The dead weight of it. The smells of blood, salt and my own sweat.

My body trembles. His Strings slip out of his Trunk and fall back at my feet, one end of them tied to my ankle and the other tied to Gill’s. I squeeze them until my knuckles whiten and gather them into my lap, resting them against Gill’s stomach.

He’s dead. He can’t be dead, but he is. He won’t disappear.

He’s more real in death than he was alive.

Suddenly panicked, I whip my head around. What if Gill’s killer is still lurking in the darkness? I don’t see anyone, but someone could be behind me, watching me. I can almost feel their breath on my neck.

Panic simmers in my gut, and the sobs burst out of me like a dam collapsing. He’s dead. This is a body. Sickened and petrified, I push him off my lap and then wipe my hands on my robes.

I’ll never have a chance to apologize for worrying him earlier.

Footsteps thump toward stage right, and Nicoleta emerges, carrying a torch. “What’s wrong?” she asks and then freezes when she reaches me and Gill. I feel like one of the rare, taxidermied animals displayed at the entrance of the Menagerie, frozen and surrounded by expressions of horror.

She doesn’t scream like I did at first, but she shudders. She inches forward, growing slower with each step, as if she doesn’t want her torchlight to fully illuminate the scene in front of her. “Is he dead?” she whispers, her eyes locked on Gill’s body.

“Yes. I came in here and found him like this. His blood...his blood is all over me,” I choke out, my voice cracking. I scrub my hands over and over with my cloak, desperate to remove the sticky red stains on my palms, desperate to feel clean even after they’ve been wiped away. My lungs don’t feel like they’re stretching properly, like walls are crushing them from both sides. Each of my inhales grows shorter, faster. My heart pounds.

This was no accident.

“Someone killed him,” I say. I sound as though I’m being strangled.

She looks at me gravely. “Get up. Come over here.” As I get to my feet, she adds, “No, no, shut his eyes first.” With trembling hands, I bend down and close his eyes. The feeling of his clammy skin makes me feel like vomiting. I remind myself that this is Gill. My bossy but well-meaning uncle. My family.

I hurry to Nicoleta and bury my face in her shoulder. “Take that off,” she says, nodding at my cloak. “You’re covered in blood. If an official comes in, what will they think? We need to clean you up and move him. Now.”

“Someone killed him,” I blubber. “He has stab wounds all over his back. Someone smashed his tank. Someone wheeled his tank here—”

Nicoleta grabs my shoulders and rips off my cloak. Despite everything, her voice is steady but sharpened by a terseness that I imagine is shock. “Did you see anyone? Hear anything?”

“No. It was so loud outside. I was just talking to him a little while ago. Then I went in to talk to you and the others, and when I came back, he was gone—”

“Can you make the body disappear?”

“No.” And even if I could, the thought of keeping Gill locked away like this inside my mind unnerves me.

“Then we need to clean all this up, hide his body.”

“I need to tell Villiam. We need to find out who did this.”

She bundles my cloak in her arms. “The officials—”

“I braved the officials for some coins. You think I won’t do it for Gill?” Again, I feel the urge to wipe my bloodstained hands, and Nicoleta holds my cloak out for me like a towel. My stomach flips. This is Gill’s blood covering me. Blood from the wounds that killed him.

“Then go, and be careful,” she says. “I’ll talk to Venera and Crown.”

I race out of the tent, half to put distance between me and the body and half in my urgency to find Villiam. As I leave, I faintly hear Nicoleta cry out, now that she’s alone with her own grief.

Outside, a few silhouettes clothed in the white glow of the torches and encased in smoke wander through the paths that wind across Gomorrah like veins. Many of them are patrons, judging by their taffeta dresses and patent shoes. They pause at each fork in the path and waver in between the hundreds of tents. The paths do not follow any logic, as they change each time Gomorrah travels to a new city.

No matter how fast I run, I cannot escape from the scene of Gill’s murder berating my mind. I try to calm myself, to prepare for speaking with Villiam. I know my father, and, despite the horror of these events, he will want facts, logic and composure in order to help. I’m not certain if I am capable of that now, but, still, I prepare my case.

After Gill and I spoke, he probably returned to the boys’ tent alone and climbed into his tank, as he always does after shows and family nights. He can climb in by himself, but he cannot climb out without the help of a ladder. It would be easy for the killer to kick the ladder aside, leaving Gill helpless within the tank. We wouldn’t be able to hear him scream within the water.

The killer then would’ve wheeled Gill to the stage. The killer must have known Gill, must have intended to kill him, specifically, and for us to find him in such a dramatic, horrible fashion, center stage.

Even from outside, I wouldn’t have heard the tank smash because of all the commotion. I wouldn’t have heard the violence of the killer stabbing him, which I’m sure he did to prevent Gill from shouting—all the wounds were at the top of his back, near his lungs. And I was too distracted by the passing official to notice anyone sneaking around outside our tent.

The killer had been there. Right there. And I’d missed him. How did I not see him? I should never have let Gill return to his tent alone. With his nose buried in a book, he probably wouldn’t notice anyone following him.

I could’ve prevented this. A helplessness churns inside me, a desperation to pinch myself and pretend this was a nightmare.

Who would want to kill Gill? He didn’t have any enemies—none of us do but especially not Gill. He kept to himself, rarely leaving our caravans or tents unless absolutely necessary. The other members of Gomorrah know him the least of all my illusions. Unless I was the real target...yet the killer would have had ample opportunity to attack me while I stood alone outside. Then again, who would target me? I may be the proprietor’s daughter, but I don’t actually possess any power.

It’s possible an Up-Mountain religious fanatic killed him. Just the thought of that makes me furious, and I curl my hands into fists. I hate the Up-Mountainers. I hate them and their hateful god.

But it couldn’t have been a random fanatic. The murderer knew where Gill slept. They knew exactly how to kill him. They knew where to kill him.

A white-coated official storms down the path and turns to a larger road. He carries a short sword in one hand, which clangs against the massive religious chain around his neck—a sword with the sun behind it, the sun representing light and Ovren, their god, and the sword symbolizing the eternal war against the “unfaithful,” or anyone who dares to practice jynx-work—who dares to exist despite the warrior god, who would have them gone. I immediately lurch back inside and wait for him to pass. I don’t trust the Up-Mountain religion, which focuses more on cleansing others of sin than cleansing oneself.

He passes, and I hurry to the path, now with my moth illusion to cloak me. It is rarely this quiet in Gomorrah at night, when everyone is awake. Usually there are the rattles of dice from within the striped tents, the crackling of a thousand torches and bonfires, and the songs of fiddles and flutes. Now there are only pounding footsteps interspersed with shrieks in the distant night.

From the direction where I am heading.

I weave through the paths, and even though they’ve changed, I know instinctively where to head, as the central points in Gomorrah always seem to fall on the same spots.

For a visitor, after walking through the mouth of Skull Gate and past the ticket booth, you’d approach the map of Gomorrah, made of thin cow’s hide stretched and bound to two ten-foot stakes. Above the map is written The Festival of Burning Desires.

Gomorrah is shaped like a coffin, with the entrance—Skull Gate—at the crown of the head and the twin obelisks at the bottom corners. The top half of the coffin is called the Uphill, and its main attractions include the Menagerie, near the forehead of the coffin; the House of Delights and Horrors, located along the left shoulder; and my Freak Show, located at the right shoulder...all from the point of view of the deceased, that is.

I pull up the hood of my cloak and sprint northeast, toward the Menagerie’s spire. The closer I run toward it, the louder the commotion becomes. Frician patrons drunkenly stumble their way back to Skull Gate, nearly as wary of the passing officials as I am. Everywhere is the shouting of arguments and confusion, and I imagine the heart of it will be around the proprietor’s tent.

I enter the clearing around the Menagerie. Gomorrah’s guards surround the entrance areas to keep the dangerous animals inside and all others out. Gomorrah officials wear all black, even over their faces, so they could blend into the Menagerie tent if not for the whites of their eyes. The Frician officials, in their tasseled, gussied uniforms, gather beneath the ruby banners in this clearing, each one depicting a different legendary animal. The officials stand straighter than toy soldiers.

Beneath the swan dragon’s banner, an argument ensues.

“We haven’t done anything wrong,” a man shouts.

Another beside him says, “You’re using pathetic excuses to shut down the Festival.”

“Let her go,” roar another four people.

At the center of the crowd, a young woman with fair skin wearing a red tiered vest struggles against the grip of one of the guards. I don’t know her name, but by her lavish jewelry and heavy makeup, I assume she works as a prettywoman in the Downhill.

“Whore,” the guard hisses at her. Her tears make her white eyeliner stream down her face.

Although the Festival’s guards remain still—they would never attack without a direct order from Villiam or their captain—a Gomorrah man rushes at the guard with a wooden staff. It doesn’t surprise me that the official’s insult riled him up. In Gomorrah, there are prostitutes and there are crooks. There are doctors and there are teachers. The Up-Mountainers consider us all the same—scum—so every profession, every person is given the same level of respect by other members of Gomorrah. No one here would dream of calling that woman anything other than her name.

The official brings down his sword and slices off all four of the man’s fingers on his left hand. Both the woman and the man scream, and I’m so shocked that my moth illusion flickers for a moment. I swerve away from the crowd as the official throws the woman down. On her knees, she cries and digs in the dirt for the fingers of the screaming man.

I lick my lips and imagine the illusions I would conjure for those officials. I could make them feel a swarm of beetles pinching every inch of their skin or see hazy, bloody specters cutting off their own fingers. But if I use jynx-work on a Frician, I’ll only cause the Festival—and Villiam—more trouble. A whole barrel full of trouble.

If that man protecting the woman had been an Up-Mountainer, the guard would’ve only hit him with the handle of his sword. Or simply yelled at him.

I’m so angry that it distracts me, for a moment, from why I am paying Villiam a visit—Gill’s body lying limp among water, blood and shards of glass. The anger dissipates, replaced by a heaviness in my chest that I recognize as grief. I immediately miss the anger.

Villiam is the priority. As much as I’d love to send the officials fleeing for their mamas and their priests through Skull Gate, I wouldn’t be helping anyone. They’d only return with more officials behind them.