полная версия

полная версияBuried Cities, Volume 2: Olympia

"It is the Hermes of Praxiteles," the excavators whispered among themselves.

In his day Praxiteles had been almost as famous as Phidias. The old Greek world had rung with his praises. Modern men had dreamed of what his statues must have been and had longed to see them. How did he shape the head? How did his bodies curve? What expression was on his faces? All these things they had wished to know. But not one of his statues had ever been found. Now here lay one before the very eyes of these excavators. They put out their hands and lovingly touched the polished marble skin. But what would they find when they lifted it?—Perhaps the nose would be gone, the face flattened by the fall, the ears broken, the beautiful marble chipped. They almost feared to lift it. But at last they did so.

When they saw the face, they were struck dumb by its beauty, and I think tears sprang into the eyes of some of them. No such perfect piece of marble had ever been found before. There was not a scratch. The skin still glowed with the polishing that Praxiteles' own hands had given it. There was even a hint of color on the lips. The soft clay bed had saved the falling statue. Here was a statue that the whole world would love. It would make the name of Olympia famous again. The excavators were proud and happy. That old ruined temple seemed indeed a sacred place to them as they gazed upon perhaps the most beautiful statue in the world.

"Surely we shall find nothing else so perfect," they said.

Yet they went on with the work. Before long Hermes' right foot was found imbedded in the clay. Its sandal still shone with the gilding put on two thousand years before. Workmen were tearing down one of the houses of the little town that had been built on the ancient ruins. Every stone in it had some old story. Pieces of fluted columns, carved capitals, broken pedestals, blocks from the temple of Zeus—all were cemented together to make these walls. The workmen pulled and chipped and lifted out piece after piece. The excavators studied each scrap to see whether it was valuable. And at last they found a baby's body. They carefully broke off the mortar. It was of creamy marble, beautifully carved. They carried it to Hermes. It fitted upon the drapery over his arm. On a rubbish heap outside the temple they had found a little marble head. They put it upon this baby's shoulders. It was badly broken, but they could see that it belonged there. So after two thousand years Hermes again smiled into the eyes of the baby Dionysus.

Other things were found. The shattered Victory was uncovered. Carefully the excavators fitted the pieces together. But the wide wings could never be made again, and the head was ruined. Even so, the statue is a beautiful thing, with its thin drapery flying in the wind.

After five years the work was finished. Now again hundreds of visitors journey to Olympia every year. They see no gleaming roofs and high-lifted statues and joyful games. They walk among sad ruins. But they can tread the gymnasium floor where Creon and many another victor wrestled. They can enter the gate of the grass-grown stadion. They can see the fallen columns of the temple of Zeus. In the museum they can see the statues of its pediments and, at the end of the long hall, they see Victory stepping toward them. They can wander on the banks of the Kladeos and the Alpheios. They can climb Mount Kronion and see the whole little plain and imagine it gay with tents and moving people.

All these things are interesting to those who like the old Greek life. But most people make the long journey only to see Hermes. In the museum, in a little room all alone, he stands, always calm and lovable, always dreaming of something beautiful, always half smiling at the coaxing baby.

PICTURES OF OLYMPIA

ENTRANCE TO STADION

This was not the gate where Charmides entered. This entrance was reserved for the judges, the competitors, and the heralds. Inside there were seats for forty-five thousand people. On one side the hill made a natural slope for seats. But on the other sides a ridge of earth had to be built up. The track was about two hundred yards long. Only the two ends have been excavated. The rest still lies deep under the sand.

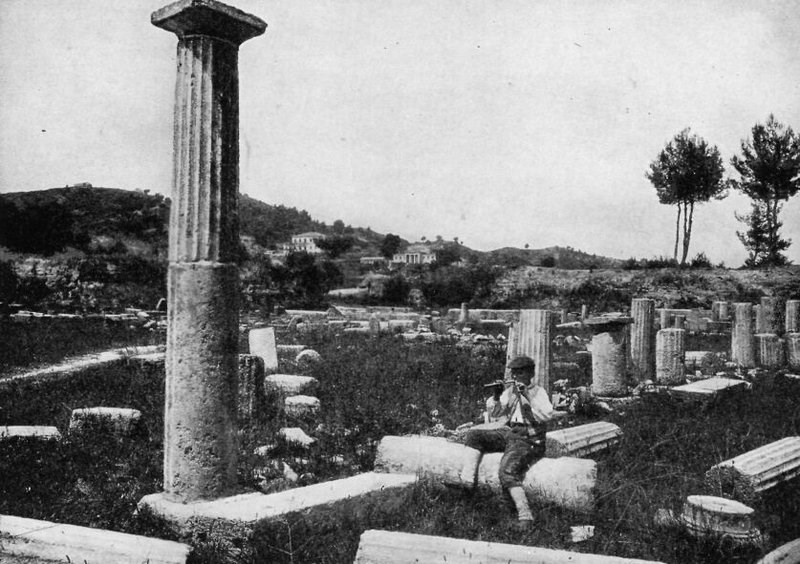

GYMNASIUM

Here Creon and the other boys spent a month in training before the games. The gymnasium had a covered portico as long as the track in the stadion, where the boys could run in bad weather. A Greek boy of to-day is playing on his shepherd's pipes in the foreground, and they are the same kind of pipes on which the old Greeks played.

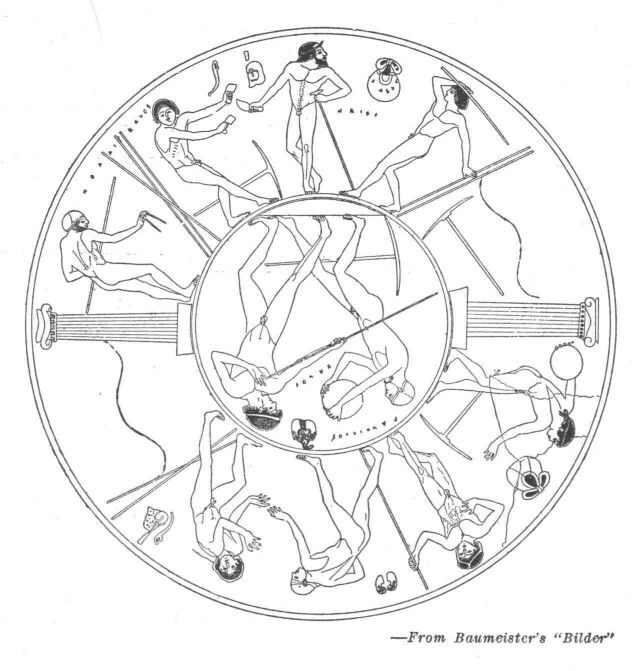

BOYS IN GYMNASIUM

From a vase painting. They are wrestling, jumping with weights, throwing the spear, throwing the discus, while their teachers watch them. One man is saying, "A beautiful boy, truly."

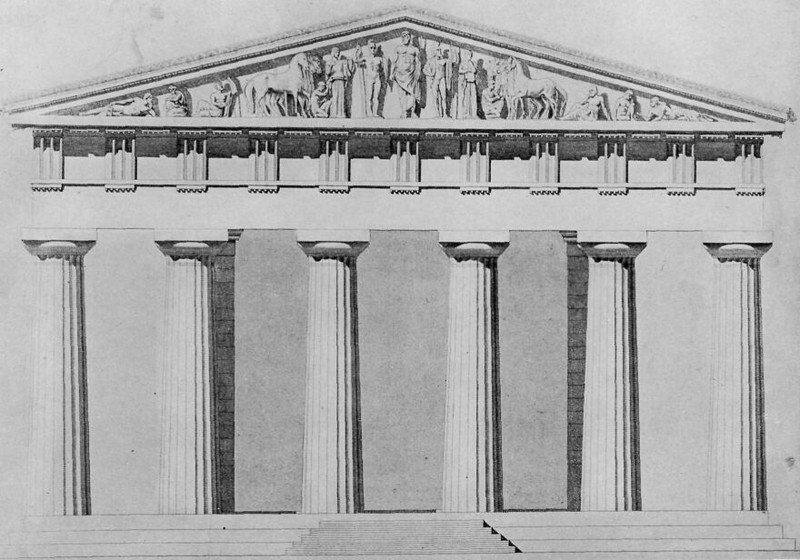

THE TEMPLE OF ZEUS

When we see a picture of fallen broken columns lying about a field in disorder, we try to learn how the original building looked and to imagine it in all its beauty. This, men believe, is the way the Temple of Zeus looked. The figures in the pediment were all of Parian marble. In the center stands Zeus himself. A chariot race is about to be run, and the contestants stand on either side of Zeus. Zeus gave the victory to Pelops, and Pelops became husband of Hippodameia, and king of Pisa, and founded the Olympic Games. These games were held every fourth year for more than a thousand years.

Note: This and the following plates of the Labors of Herakles and the statue of Victory, were photographed from Curtius and Adler's "Olympia: Die Ergebnisse der von dem Deutschen Reich Veranstalteten Ausgrabung," etc. This is one of the most beautiful books ever made for a buried city.

Boys and girls who can reach the Metropolitan Museum Library should not miss it. It is in many volumes, each almost as large as the top of the table, and you do not need to read German to appreciate the plates.

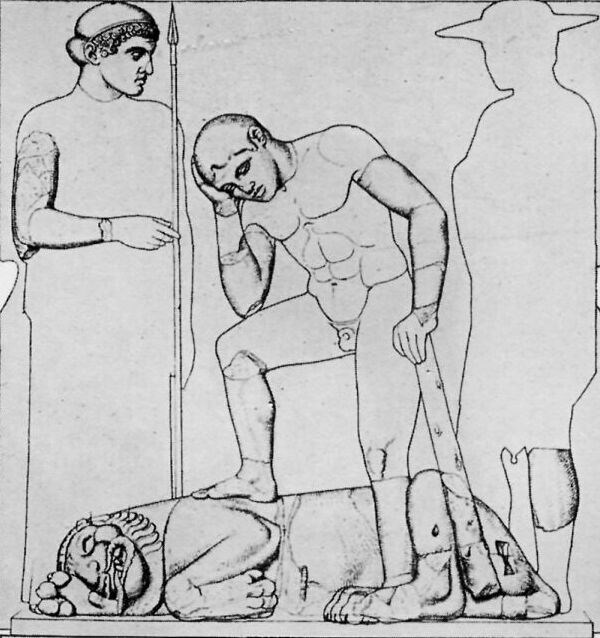

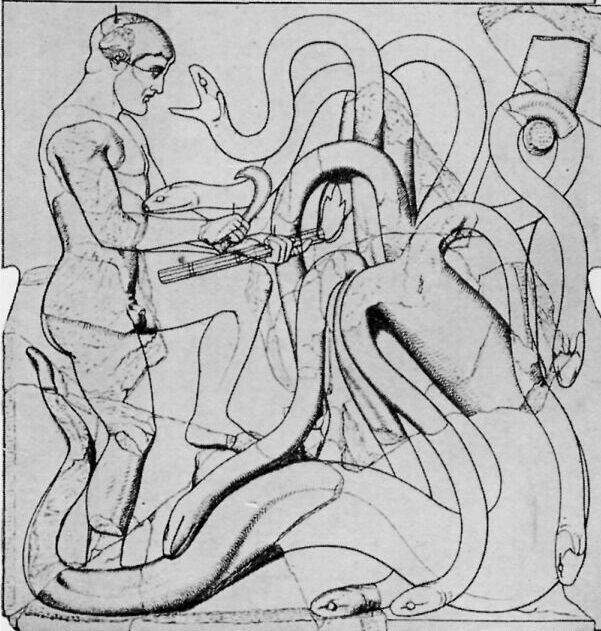

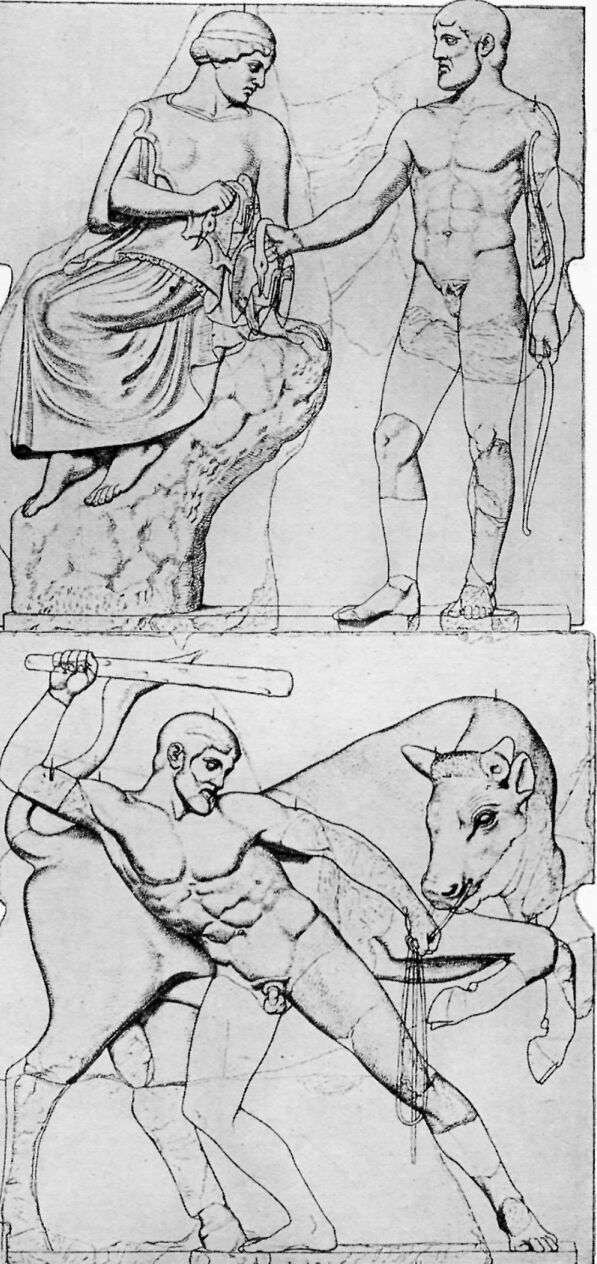

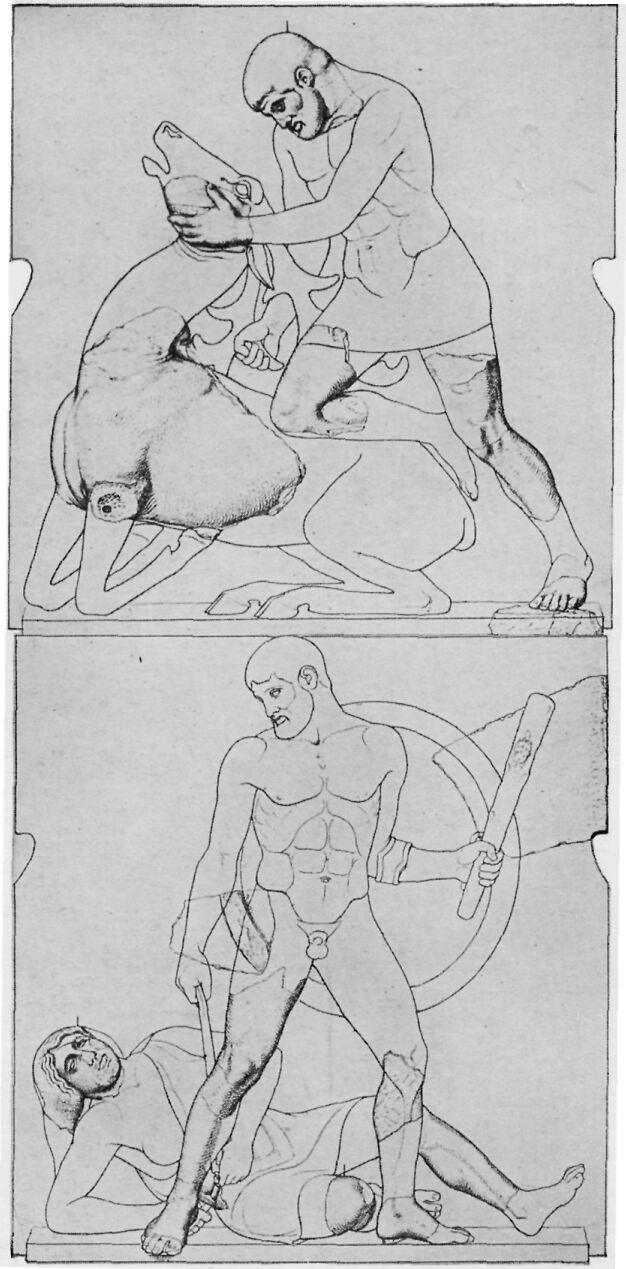

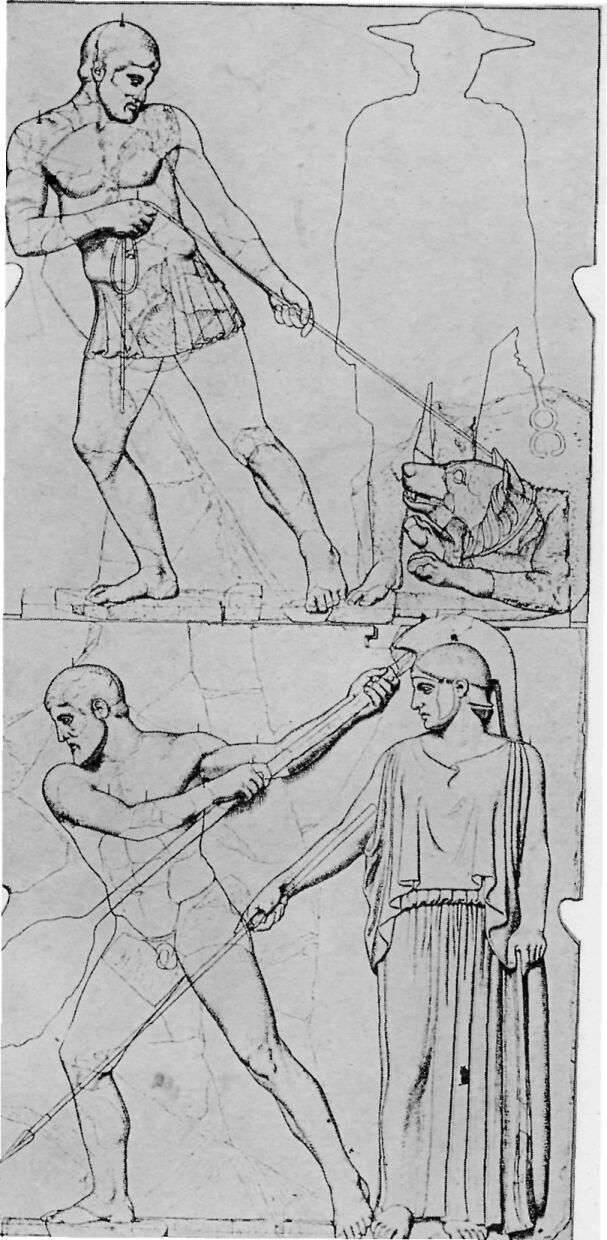

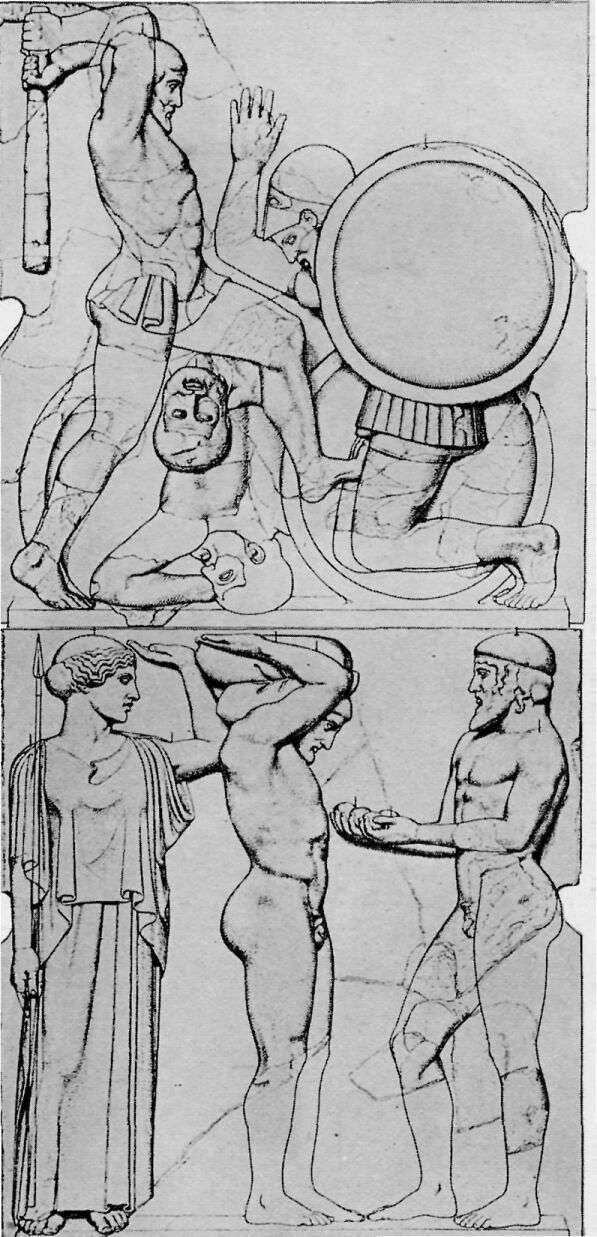

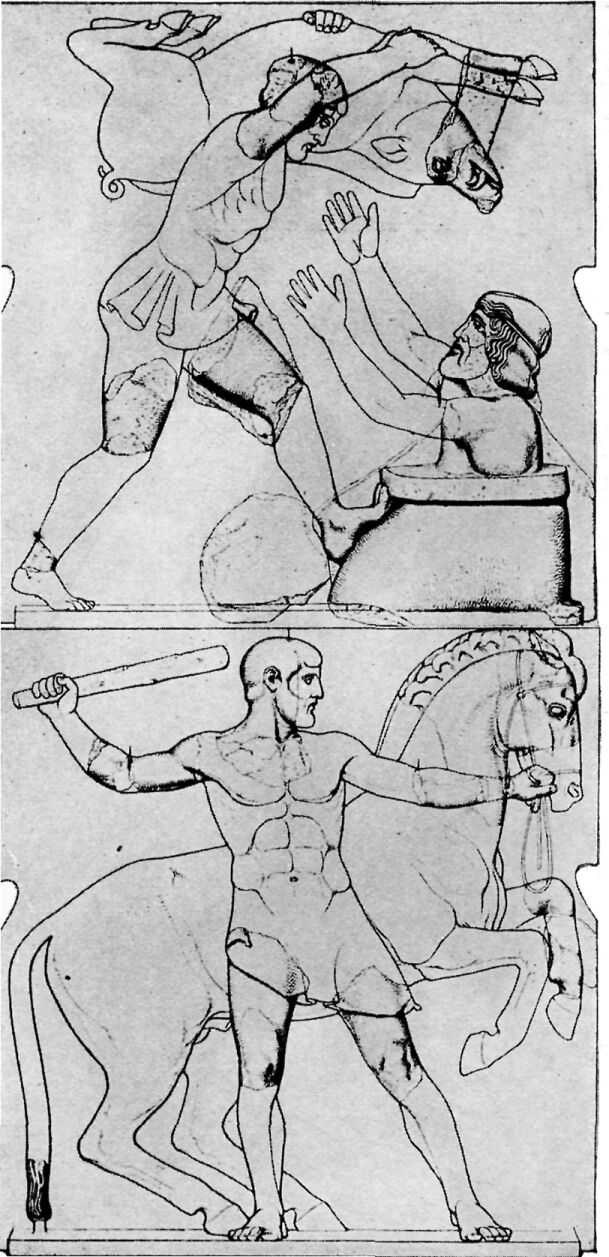

THE LABORS OF HERAKLES

Under the porches of the Temple of Zeus were twelve pictures in marble, six at each end, showing the Labors of Herakles. Herakles was highly honored at Olympia and, according to one tale, he, instead of Pelops, was the founder of the Olympic Games.

[Herakles and the Nemean lion.—Metropolitan Museum]

[Herakles and the hydra.—Metropolitan Museum]

THE STATUE OF VICTORY

In the sand, not far from the Temple of Zeus, the explorers found the fragments of this statue. It shows the goddess flying down from heaven to bring victory to the men of Messene and Naupaktos. So the victors must have erected this statue at Olympia in gratitude.

Something like the picture used as the frontispiece, men believe the statue looked originally. It stood upon a base thirty feet high so that the goddess really looked as if she were descending from heaven.

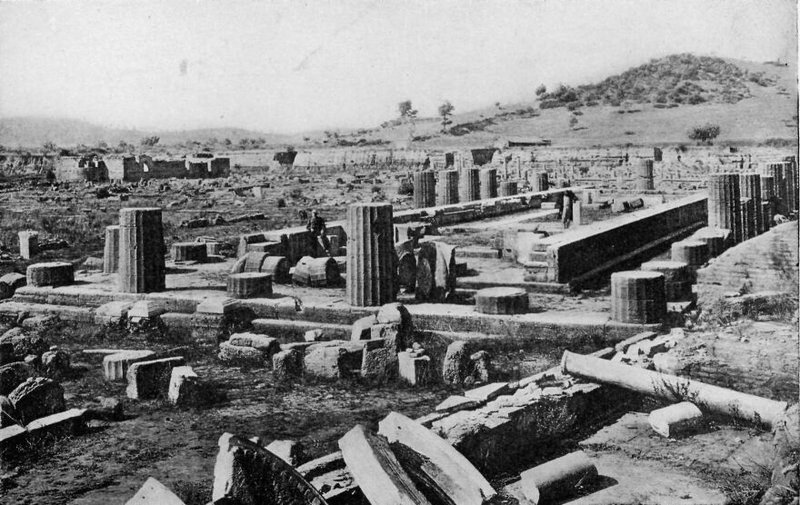

THE TEMPLE OF HERA

This shows the ruins of the temple where Charmides saw the statue of Hermes, perhaps the most beautiful statue in the world.

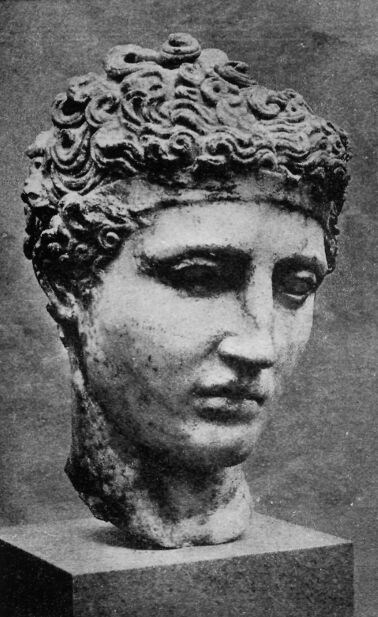

HEAD OF AN ATHLETE

The Greek artist who made this statue believed that a beautiful body is glorious, as well as a beautiful mind, and a fine spirit. Do you think his statue shows all these things? The original is now at the Metropolitan Museum.

A GREEK HORSEMAN

The artist had great skill who could chisel out of marble such a strong, bold rider, and such a spirited horse.

This picture and the one before it are not pictures of things found at Olympia. They are two of the most beautiful statues of Greek athletes, and we give them to remind you of the sort of people who came to the games at Olympia.