полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 1

One of the most intelligent and enterprising of the early privateers was Commodore Joshua Barney, a veteran of the American Navy of the Revolution. He commissioned a Baltimore schooner, the "Rossie," at the outbreak of the war; partly, apparently, in order to show a good example of patriotic energy, but doubtless also through the promptings of a love of adventure, not extinguished by advancing years. The double motive kept him an active, useful, and distinguished public servant throughout the war. His cruise on this occasion, as far as can be gathered from the reports,505 conformed in direction to the quarters in which the enemy's merchant ships might most surely be expected. Sailing from the Chesapeake July 15, he seems to have stood at once outside the Gulf Stream for the eastern edge of the Banks of Newfoundland. In the ensuing two weeks he was twice chased by an enemy's frigate, and not till July 31 did he take his first prize. From that day, to and including August 9, he captured ten other vessels—eleven in all. Unfortunately, the precise locality of each seizure is not given, but it is inferable from the general tenor of the accounts that they were made between the eastern edge of the Great Banks and the immediate neighborhood of Halifax; in the locality, in fact, to which Hull during those same ten days was directing the "Constitution," partly in pursuit of prizes, equally in search of the enemy's ships of war, which were naturally to be sought at those centres of movement where their national traders accumulated.

On August 30 the "Rossie," having run down the Nova Scotia coast and passed by George's Bank and Nantucket, went into Newport, Rhode Island. It is noticeable that before and after those ten days of success, although she saw no English vessels, except ships of war cruising on the outer approaches of their commerce, she was continually meeting and speaking American vessels returning home. These facts illustrate the considerations governing privateering, and refute the plausible opinion often advanced, that it was a mere matter of gambling adventure. Thus Mr. Gallatin, the Secretary of the Treasury, in a communication to Congress, said: "The occupation of privateers is precisely of the same species as the lottery, with respect to hazard and to the chance of rich prizes."506 Gallatin approached the subject from the standpoint of the financier and with the abstract ideas of the political economist. His temporary successor, the Secretary of the Navy, Mr. Jones, had been a merchant in active business life, and he viewed privateering as a practical business undertaking. "The analogy between privateering and lotteries does not appear to me to be so strict as the Secretary seems to consider it. The adventure of a privateer is of the nature of a commercial project or speculation, conducted by commercial men upon principles of mercantile calculation and profit. The vessel and her equipment is a matter of great expense, which is expected to be remunerated by the probable chances of profit, after calculating the outfit, insurance, etc., as in a regular mercantile voyage."507 Mr. Jones would doubtless have admitted what Gallatin alleged, that the business was liable to be overdone, as is the case with all promising occupations; and that many would engage in it without adequate understanding or forethought.

The elements of risk which enter into privateering are doubtless very great, and to some extent baffle calculation. In this it only shares the lot common to all warlike enterprise, in which, as the ablest masters of the art repeatedly affirm, something must be allowed for chance. But it does not follow that a reasonable measure of success may not fairly be expected, where sagacious appreciation of well-known facts controls the direction of effort, and preparation is proportioned to the difficulties to be encountered. Heedlessness of conditions, or recklessness of dangers, defeat effort everywhere, as well as in privateering; nor is even the chapter of unforeseen accident confined to military affairs. In 1812 the courses followed by the enemy's trade were well understood, as were also the characteristics of their ships of war, in sailing, distribution, and management.508 Regard being had to these conditions, the pecuniary venture, which privateering essentially is, was sure of fair returns—barring accidents—if the vessels were thoroughly well found, with superior speed and nautical qualities, and if directed upon the centres of ocean travel, such as the approaches to the English Channel, or, as before noted, to where great highways cross, inducing an accumulation of vessels from several quarters. So pursued, privateering can be made pecuniarily successful, as was shown by the increasing number and value of prizes as the war went on. It has also a distinct effect as a minor offensive operation, harassing and weakening the enemy; but its merits are more contestable when regarded as by itself alone decisive of great issues. Despite the efficiency and numbers of American privateers, it was not British commerce, but American, that was destroyed by the war.

From Newport the "Rossie" took a turn through another lucrative field of privateering enterprise, the Caribbean Sea. Passing by Bermuda, which brought her in the track of vessels from the West Indies to Halifax, she entered the Caribbean at its northeastern corner, by the Anegada Passage, near St. Thomas, thence ran along the south shore of Porto Rico, coming out by the Mona Passage, between Porto Rico and Santo Domingo, and so home by the Gulf Stream. In this second voyage she made but two prizes; and it is noted in her log book that she here met the privateer schooner "Rapid" from Charleston, fifty-two days out, without taking anything. The cause of these small results does not certainly appear; but it may be presumed that with the height of the hurricane season at hand, most of the West India traders had already sailed for Europe. Despite all drawbacks, when the "Rossie" returned to Baltimore toward the end of October, she had captured or destroyed property roughly reckoned at a million and a half, which is probably an exaggerated estimate. Two hundred and seventeen prisoners had been taken.

While the "Rossie" was on her way to the West Indies, there sailed from Salem a large privateer called the "America," the equipment and operations of which illustrated precisely the business conception which attached to these enterprises in the minds of competent business men. This ship-rigged vessel of four hundred and seventy-three tons, built of course for a merchantman, was about eight years old when the war broke out, and had just returned from a voyage. Seeing that ordinary commerce was likely to be a very precarious undertaking, her owners spent the months of July and August in preparing her deliberately for her new occupation. Her upper deck was removed, and sides filled in solid. She was given larger yards and loftier spars than before; the greatly increased number of men carried by a privateer, for fighting and for manning prizes, enabling canvas to be handled with greater rapidity and certainty. She received a battery of very respectable force for those days, so that she could repel the smaller classes of ships of war, which formed a large proportion of the enemy's cruisers. Thus fitted to fight or run, and having very superior speed, she was often chased, but never caught. During the two and a half years of war she made four cruises of four months each; taking in all forty-one prizes, twenty-seven of which reached port and realized $1,100,000, after deducting expenses and government charges. As half of this went to the ship's company, the owners netted $550,000 for sixteen months' active use of the ship. Her invariable cruising ground was from the English Channel south, to the latitude of the Canary Islands.509

The United States having declared war, the Americans enjoyed the advantage of the first blow at the enemy's trade. The reduced numbers of vessels on the British transatlantic stations, and the perplexity induced by Rodgers' movement, combined to restrict the injury to American shipping. A number of prizes were made, doubtless; but as nearly as can be ascertained not over seventy American merchant ships were taken in the first three months of the war. Of these, thirty-eight are reported as brought under the jurisdiction of the Vice-Admiralty Court at Halifax, and twenty-four as captured on the Jamaica station. News of the war not being received by the British squadrons in Europe until early in August, only one capture there appears before October 1, except from the Mediterranean. There Captain Usher on September 6 wrote from Gibraltar that all the Americans on their way down the Sea—that is, out of the Straits—had been taken.510 In like manner, though with somewhat better fortune, thirty or forty American ships from the Baltic were driven to take refuge in the neutral Swedish port of Gottenburg, and remained war-bound.511 That the British cruisers were not inactive in protecting the threatened shores and waters of Nova Scotia and the St. Lawrence is proved by the seizure of twenty-four American privateers, between July 1 and August 25;512 a result to which the inadequate equipment of these vessels probably contributed. But American shipping, upon the whole, at first escaped pretty well in the matter of actual capture.

It was not in this way, but by the almost total suppression of commerce, both coasting and foreign, both neutral and American, that the maritime pressure of war was brought home to the United States. This also did not happen until a comparatively late period. No commercial blockade was instituted by the enemy before February, 1813. Up to that time neutrals, not carrying contraband, had free admission to all American ports; and the British for their own purposes encouraged a licensed trade, wholly illegitimate as far as United States ships were concerned, but in which American citizens and American vessels were largely engaged, though frequently under flags of other nations. A significant indication of the nature of this traffic is found in the export returns of the year ending September 30, 1813. The total value of home produce exported was $25,008,152, chiefly flour, grain, and other provisions. Of this, $20,536,328 went to Spain and Portugal with their colonies; $15,500,000 to the Peninsula itself.513 It was not till October, 1813, when the British armies entered France, that this demand fell. At the same time Halifax and Canada were being supplied with flour from New England; and the common saying that the British forces in Canada could not keep the field but for supplies sent from the United States was strictly true, and has been attested by British commissaries. An American in Halifax in November, 1812, wrote home that within a fortnight twenty thousand barrels of flour had arrived in vessels under Spanish and Swedish flags, chiefly from Boston. This sort of unfaithfulness to a national cause is incidental to most wars, but rarely amounts to as grievous a military evil as in 1812 and 1813, when both the Peninsula and Canada were substantially at our mercy in this respect. With the fall of Napoleon, and the opening of Continental resources, such control departed from American hands. In the succeeding twelvemonth there was sent to the Peninsula less than $5,000,000 worth.

Warren's impressions of the serious nature of the opening conflict caused a correspondence between him and the Admiralty somewhat controversial in tone. Ten days after his arrival he represented the reduced state of the squadron: "The war assumes a new, as well as more active and inveterate aspect than heretofore." Alarming reports were being received as to the number of ships of twenty-two to thirty-two guns fitting out in American ports, and he mentions as significant that the commission of a privateer officer, taken in a recaptured vessel, bore the number 318. At Halifax he was in an atmosphere of rumors and excitement, fed by frequent communication with eastern ports, as well as by continual experience of captures about the neighboring shores; the enemies' crews even landing at times. When he went to Bermuda two months later, so many privateers were met on the line of traffic between the West Indies and the St. Lawrence as to convince him of the number and destructiveness of these vessels, and "of the impossibility of our trade navigating these seas unless a very extensive squadron is employed to scour the vicinity." He was crippled for attempting this by the size of the American frigates, which forbade his dispersing his cruisers. The capture of the "Guerrière" had now been followed by that of the "Macedonian;" and in view of the results, and of Rodgers being again out, he felt compelled to constitute squadrons of two frigates and a sloop. Under these conditions, and with so many convoys to furnish, "it is impracticable to cut off the enemy's resources, or to repress the disorder and pillage which actually exist to a very alarming degree, both on the coast of British America and in the West Indies, as will be seen by the copies of letters enclosed," from colonial and naval officials. He goes on to speak, in terms not carefully weighed, of swarms of privateers and letters-of-marque, their numbers now amounting to six hundred; the crews of which had landed in many points of his Majesty's dominions, and even taken vessels from their anchors in British ports.514

The Admiralty, while evidently seeing exaggeration in this language, bear witness in their reply to the harassment caused by the American squadrons and private armed ships. They remind the admiral that there are two principal ways of protecting the trade: one by furnishing it with convoys, the other by preventing egress from the enemy's ports, through adequate force placed before them. To disperse vessels over the open sea, along the tracks of commerce, though necessary, is but a subsidiary measure. His true course is to concentrate a strong division before each chief American port, and they intimate dissatisfaction that this apparently had not yet been done. As a matter of fact, up to the spring of 1813, American ships of war had little difficulty in getting to sea. Rodgers had sailed again with his own squadron and Decatur's on October 8, the two separating on the 11th, though this was unknown to the British; and Bainbridge followed with the "Constitution" and "Hornet" on the 26th. Once away, power to arrest their depredations was almost wholly lost, through ignorance of their intentions. With regard to commerce, they were on the offensive, the British on the defensive, with the perplexity attaching to the latter rôle.

Under the circumstances, the Admiralty betrays some impatience with Warren's clamor for small vessels to be scattered in defence of the trade and coasts. They remind him that he has under his flag eleven sail of the line, thirty-four frigates, thirty-eight sloops, besides other vessels, making a total of ninety-seven; and yet first Rodgers, and then Bainbridge, had got away. True, Boston cannot be effectively blockaded from November to March, but these two squadrons had sailed in October. Even "in the month of December, though it was not possible perhaps to have maintained a permanent watch on that port, yet having, as you state in your letter of November 5, precise information that Commodore Bainbridge was to sail at a given time, their Lordships regret that it was not deemed practicable to proceed off that port at a reasonable and safe distance from the land, and to have taken the chance at least of intercepting the enemy." "The necessity for sending heavy convoys arises from the facility and safety with which the American navy has hitherto found it possible to put to sea. The uncertainty in which you have left their Lordships, in regard to the movements of the enemy and the disposition of your own force, has obliged them to employ six or seven sail of the line and as many frigates and sloops, independent of your command, in guarding against the possible attempts of the enemy. Captain Prowse, with two sail of the line, two frigates, and a sloop, has been sent to St. Helena. Rear-Admiral Beauclerk, with two of the line, two frigates, and two sloops, is stationed in the neighborhood of Madeira and the Azores, lest Commodore Bainbridge should have come into that quarter to take the place of Commodore Rodgers, who was retiring from it about the time you state Commodore Bainbridge was expected to sail. Commodore Owen, who had preceded Admiral Beauclerk in this station, with a ship of the line and three other vessels, is not yet returned from the cruise on which the appearance of the enemy near the Azores had obliged their Lordships to send this force; while the 'Colossus' and the 'Elephant' [ships of the line], with the 'Rhin' and the 'Armide,' are but just returned from similar services. Thus it is obvious that, large as the force under your orders was, and is, it is not all that has been opposed to the Americans, and that these services became necessary only because the chief weight of the enemy's force has been employed at a distance from your station."515

The final words here quoted characterize exactly the conditions of the first eight or ten months of the war, until the spring of 1813. They also define the purpose of the British Government to close the coast of the United States in such manner as to minimize the evils of widely dispersed commerce-destroying, by confining the American vessels as far as possible within their harbors. The American squadrons and heavy frigates, which menaced not commerce only but scattered ships of war as well, were to be rigorously shut up by an overwhelming division before each port in which they harbored; and the Admiralty intimated its wish that a ship of the line should always form one of such division. This course of policy, initiated when the winter of 1812-13 was over, was thenceforth maintained with ever increasing rigor; especially after the general peace in Europe, in May, 1814, had released the entire British navy. It had two principal results. The American frigates were, in the main, successfully excluded from the ocean. Their three successful battles were all fought before January 1, 1813. Commodore John Rodgers, indeed, by observing his own precept of clinging to the eastern ports of Newport and Boston, did succeed after this in making two cruises with the "President;" but entering New York with her on the last of these, in February, 1814, she was obliged, in endeavoring to get to sea when transferred to Decatur, to do so under circumstances so difficult as to cause her to ground, and by consequent loss of speed to be overtaken and captured by the blockading squadron. Captain Stewart reported the "Constitution" nearly ready for sea, at Boston, September 26, 1813. Three months after, he wrote the weather had not yet enabled him to escape. On December 30, however, she sailed; but returning on April 4, the blockaders drove her into Salem, whence she could not reach Boston until April 17, 1814, and there remained until the 17th of the following December. Her last successful battle, under his command, was on February 20, 1815, more than two years after she captured the "Java." When the war ended the only United States vessels on the ocean were the "Constitution," three sloops—the "Wasp," "Hornet," and "Peacock "—and the brig "Tom Bowline." The smaller vessels of the navy, and the privateers, owing to their much lighter draft, got out more readily; but neither singly nor collectively did they constitute a serious menace to convoys, nor to the scattered cruisers of the enemy. These, therefore, were perfectly free to pursue their operations without fear of surprise.

On the other hand, because of this concentration along the shores of the United States, the vessels that did escape went prepared more and more for long absences and distant operations. On the sea "the weight of the enemy's force," to use again the words of the Admiralty, "was employed at a distance from the North American station." Whereas, at the first, most captures by Americans were made near the United States, after the spring of 1813 there is an increasing indication of their being most successfully sought abroad; and during the last nine months of the war, when peace prevailed throughout the world except between the United States and Great Britain, when the Chesapeake was British waters, when Washington was being burned and Baltimore threatened, when the American invasion of Canada had given place to the British invasion of New York, when New Orleans and Mobile were both being attacked,—it was the coasts of Europe, and the narrow seas over which England had claimed immemorial sovereignty, that witnessed the most audacious and successful ventures of American cruisers. The prizes taken in these quarters were to those on the hither side of the Atlantic as two to one. To this contributed also the commercial blockade, after its extension over the entire seaboard of the United States, in April, 1814. The practically absolute exclusion of American commerce from the ocean is testified by the exports of 1814, which amounted to not quite $7,000,000;516 whereas in 1807, the last full year of unrestricted trade, they had been $108,000,000.517 Deprived of all their usual employments, shipping and seamen were driven to privateering to earn any returns at all.

From these special circumstances, the period from June, 1812, when the war began, to the end of April, 1813, when the departure of winter conditions permitted the renewal of local activity on sea and land, had a character of its own, favoring the United States on the ocean, which did not recur. Some specific account of particular transactions during these months will serve to illustrate the general conditions mentioned.

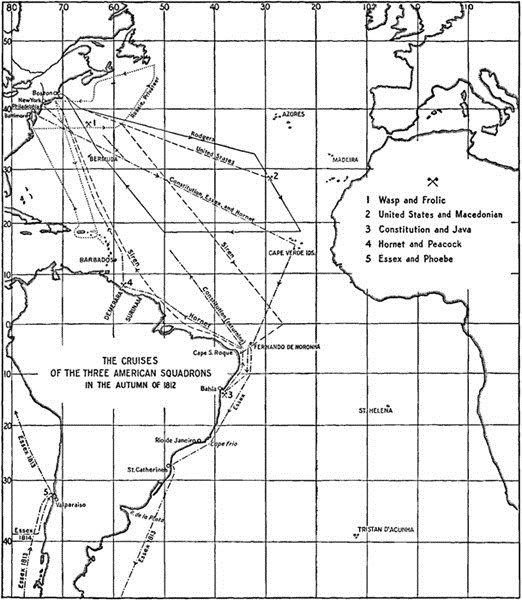

When Warren reached Halifax, there were still in Boston the "Constitution" and the ships that had returned with Rodgers on August 31. From these the Navy Department now constituted three squadrons. The "Hornet," Captain James Lawrence, detached from Rodgers' command, was attached to the "Constitution," in which Captain William Bainbridge had succeeded Hull. Bainbridge's squadron was to be composed of these two vessels and the smaller 32-gun frigate "Essex," Captain David Porter, then lying in the Delaware. Rodgers retained his own ship, the "President," with the frigate "Congress;" while to Decatur was continued the "United States" and the brig "Argus." These detachments were to act separately under their several commodores; but as Decatur's preparations were only a few days behind those of Rodgers, the latter decided to wait for him, and on October 8 the two sailed in company, for mutual support until outside the lines of enemies, in case of meeting with a force superior to either singly.

In announcing his departure, Rodgers wrote the Department that he expected the British would be distributed in divisions, off the ports of the coast, and that if reliable information reached him of any such exposed detachment, it would be his duty to seek it. "I feel a confidence that, with prudent policy, we shall, barring unforeseen accidents, not only annoy their commerce, but embarrass and perplex the commanders of their public ships, equally to the advantage of our commerce and the disadvantage of theirs." Warren and the Admiralty alike have borne witness to the accuracy of this judgment. Rodgers was less happy in another forecast, in which he reflected that of his countrymen generally. As regards the reported size of British re-enforcements to America, "I do not feel confidence in them, as I cannot convince myself that their resources, situated as England is at present, are equal to the maintenance of such a force on this side of the Atlantic; and at any rate, if such an one do appear, it will be only with a view to bullying us into such a peace as may suit their interests."518 The Commodore's words reflected often an animosity, personal as well as national, aroused by the liberal abuse bestowed on him by British writers.

THE CRUISES OF THE THREE AMERICAN SQUADRONS IN THE AUTUMN OF 1812

On October 11 Decatur's division parted company, the "President" and "Congress" continuing together and steering to the eastward. On the 15th the two ships captured a British packet, the "Swallow," from Jamaica to Falmouth, having $150,000 to $200,000 specie on board; and on the 31st, in longitude 32° west, latitude 33° north, two hundred and forty miles south of the Azores, a Pacific whaler on her homeward voyage was taken. These two incidents indicate the general direction of the course held, which was continued to longitude 22° west, latitude 17° north, the neighborhood of the Cape Verde group. This confirms the information of the British Admiralty that Rodgers was cruising between the Azores and Madeira; and it will be seen that Bainbridge, as they feared, followed in Rodgers' wake, though with a different ulterior destination. The ground indeed was well chosen to intercept homeward trade from the East Indies and South America. Returning, the two frigates ran west in latitude 17°, with the trade wind, as far as longitude 50°, whence they steered north, passing one hundred and twenty miles east of Bermuda. In his report to the Navy Department Rodgers said that he had sailed almost eleven thousand miles, making the circuit of nearly the whole western Atlantic. In this extensive sweep he had seen only five enemy's merchant vessels, two of which were captured. The last four weeks, practically the entire month of December, had been spent upon the line between Halifax and Bermuda, without meeting a single enemy's ship. From this he concluded that "their trade is at present infinitely more limited than people imagine."519 In fact, however, the experience indicated that the British officials were rigorously enforcing the Convoy Law, according to the "positive directions," and warnings of penalties, issued by the Government. A convoy is doubtless a much larger object than a single ship; but vessels thus concentrated in place and in time are more apt to pass wholly unseen than the same number sailing independently, and so scattered over wide expanses of sea.