полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 1

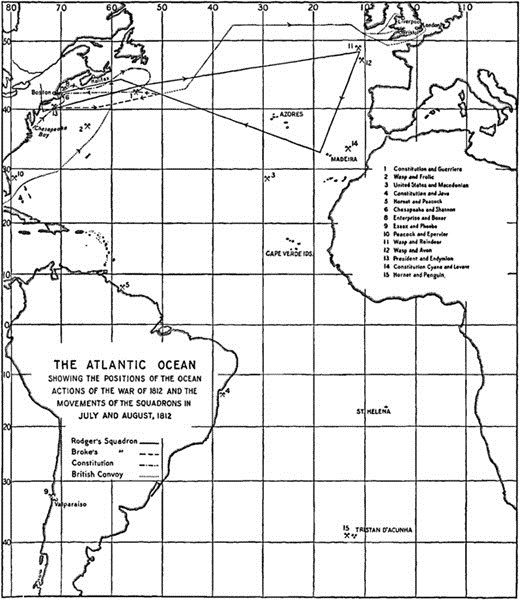

After some little delay in repairing, the squadron resumed pursuit of the convoy. On June 29, and again on July 9, vessels were spoken which reported encountering it; the latter the evening before. Traces of its course also were thought to be found in quantities of cocoanut shell and orange peel, passed on one occasion; but, though the chase was continued to within twenty hours' sail of the English Channel, the convoy itself was never seen. To this disappointing result atmospheric conditions very largely contributed. From June 29, on the western edge of the Great Banks, until July 13, when the pursuit was abandoned, the weather was so thick that "at least six days out of seven" nothing was visible over five miles away, and for long periods the vessels could not even see one another at a distance of two hundred yards. The same surrounding lasted to the neighborhood of Madeira, for which the course was next shaped. After passing that island on June 21 return was made toward the United States by way of the Azores, which were sighted, and thence again to the Banks of Newfoundland and Cape Sable, reaching Boston August 31, after an absence of seventy days.

Although Rodgers's plan had completely failed in what may properly be called its purpose of offence, and he could report the capture of "only seven merchant vessels, and those not valuable," he congratulated himself with justice upon success on the defensive side.423 The full effect was produced, which he had anticipated from the mere fact of a strong American division being at large, but seen so near its own shores that nothing certain could be inferred as to its movements or intentions. The "Belvidera," having lost sight of it at midnight, could, upon her arrival in Halifax, give only the general information that it was at sea; and Captain Byron, who commanded her, thought with reason that the "President's" action warranted the conclusion that the anticipated hostilities had been begun. He therefore seized and brought in two or three American merchantmen; but the British admiral, Sawyer, thinking there might possibly be some mistake, like that of the meeting between the "President" and "Little Belt" a year before, directed their release.

A very few days later, definite intelligence of the declaration of war by the United States was received at Halifax. At that period, the American seas from the equator to Labrador were for administrative purposes divided by the British Admiralty into four commands: two in the West Indies, centring respectively at Jamaica and Barbados; one at Newfoundland; while the fourth, with its two chief naval bases of Halifax and Bermuda, lay over against the United States, and embraced the Atlantic coast-line in its field of operations. Admiral Sawyer now promptly despatched a squadron, consisting of one small ship of the line and three frigates, the "Shannon", 38, "Belvidera", 36, and "Æolus", 32, which sailed July 5. Four days later, off Nantucket, it was joined by the "Guerrière", 38, and July 14 arrived off Sandy Hook. There Captain Broke, of the "Shannon", who by seniority of rank commanded the whole force, "received the first intelligence of Rodgers' squadron having put to sea."424 As an American division of some character had been known to be out since the "Belvidera" met it, and as Rodgers on this particular day was within two days' sail of the English Channel, the entire ignorance of the enemy as to his whereabouts could not be more emphatically stated. The components of the British force were such that no two of them could justifiably venture to encounter his united command. Consequently, to remain together was imposed as a military necessity, and it so continued for some weeks. In fact, the first separation, that of the "Guerrière", though apparently necessary and safe, was followed immediately by a disaster.

Rodgers was therefore justified in his claim concerning his cruise. "It is truly unpleasant to be obliged to make a communication thus barren of benefit to our country. The only consolation I, individually, feel on the occasion is derived from knowing that our being at sea obliged the enemy to concentrate a considerable portion of his most active force, and thereby prevented his capturing an incalculable amount of American property that would otherwise have fallen a sacrifice." "My calculations were," he wrote on another occasion, "even if I did not succeed in destroying the convoy, that leaving the coast as we did would tend to distract the enemy, oblige him to concentrate a considerable portion of his active navy, and at the same time prevent his single cruisers from lying before any of our principal ports, from their not knowing to which, or at what moment, we might return."425 This was not only a perfectly sound military conception, gaining additional credit from the contrasted views of Decatur and Bainbridge, but it was applied successfully at the most critical moment of all wars, namely, when commerce is flocking home for safety, and under conditions particularly hazardous to the United States, owing to the unusually large number of vessels then out. "We have been so completely occupied in looking out for Commodore Rodgers' squadron," wrote an officer of the "Guerrière", "that we have taken very few prizes."426 President Madison in his annual message427 said: "Our trade, with little exception, has reached our ports, having been much favored in it by the course pursued by a squadron of our frigates under the command of Commodore Rodgers."

THE ATLANTIC OCEAN, SHOWING THE POSITIONS OF THE OCEAN ACTIONS OF THE WAR OF 1812 AND THE MOVEMENTS OF THE SQUADRONS IN JULY AND AUGUST, 1812

Nor was it only the offensive action of the enemy against the United States' ports and commerce that was thus hampered. Unwonted defensive measures were forced upon him. Uncertainty as to Rodgers' position and intentions led Captain Broke, on July 29, to join a homeward-bound Jamaica fleet, under convoy of the frigate "Thalia", some two or three hundred miles to the southward and eastward of Halifax, and to accompany it with his division five hundred miles on its voyage. The place of this meeting shows that it was pre-arranged, and its distance from the American coast, five hundred miles away from New York, together with the length of the journey through which the additional guard was thought necessary, emphasize the effect of Rodgers' unknown situation upon the enemy's movements. The protection of their own trade carried this British division a thousand miles away from the coast it was to threaten. It is in such study of reciprocal action between enemies that the lessons of war are learned, and its principles established, in a manner to which the study of combats between single ships, however brilliant, affords no equivalent. The convoy that Broke thus accompanied has been curiously confused with the one of which Rodgers believed himself in pursuit;428 and the British naval historian James chuckles obviously over the blunder of the Yankee commodore, who returned to Boston "just six days after the 'Thalia', having brought home her charge in safety, had anchored in the Downs." Rodgers may have been wholly misinformed as to there being any Jamaica convoy on the way when he started; but as on July 29 he had passed Madeira on his way home, it is obvious that the convoy which Broke then joined south of Halifax could not be the one the American squadron believed itself to be pursuing across the Atlantic a month earlier.

Broke accompanied the merchant ships to the limits of the Halifax station. Then, on August 6, receiving intelligence of Rodgers having been seen on their homeward path, he directed the ship of the line, "Africa", to go with them as far as 45° W., and for them thence to follow latitude 52° N., instead of the usual more southerly route.429 After completing this duty the "Africa" was to return to Halifax, whither the "Guerrière", which needed repairs, was ordered at once. The remainder of the squadron returned off New York, where it was again reported on September 10. The movement of the convoy, and the "Guerrière's" need of refit, were linked events that brought about the first single-ship action of the war; to account for which fully the antecedent movements of her opponent must also be traced. At the time Rodgers sailed, the United States frigate "Constitution", 44, was lying at Annapolis, enlisting a crew. Fearing to be blockaded in Chesapeake Bay, a position almost hopeless, her captain, Hull, hurried to sea on July 12. July 17, the ship being then off Egg Harbor, New Jersey, some ten or fifteen miles from shore, bound to New York, Broke's vessels, which had then arrived from Halifax for the first time in the war, were sighted from the masthead, to the northward and inshore of the "Constitution". Captain Hull at first believed that this might be the squadron of Rodgers, of whose actual movements he had no knowledge, waiting for him to join in order to carry out commands of the Department. Two hours later, another sail was discovered to the northeast, off shore. The perils of an isolated ship, in the presence of a superior force of possible enemies, imposed caution, so Hull steered warily toward the single unknown. Attempting to exchange signals, he soon found that he neither could understand nor be understood. To persist on his course might surround him with foes, and accordingly, about 11 P.M., the ship was headed to the southeast and so continued during the night.

The next morning left no doubt as to the character of the strangers, among whom was the "Guerrière"; and there ensued a chase which, lasting from daylight of July 18th to near noon of the 20th, has become historical in the United States Navy, from the attendant difficulties and the imminent peril of the favorite ship endangered. Much of the pursuit being in calm, and on soundings, resort was had to towing by boats, and to dragging the ship ahead by means of light anchors dropped on the bottom. In a contest of this kind, the ability of a squadron to concentrate numbers on one or two ships, which can first approach and cripple the enemy, thus holding him till their consorts come up, gives an evident advantage over the single opponent. On the other hand, the towing boats of the pursuer, being toward the stern guns of the pursued, are the first objects on either side to come under fire, and are vulnerable to a much greater degree than the ships themselves. Under such conditions, accurate appreciation of advantages, and unremitting use of small opportunities, are apt to prove decisive. It was by such diligent and skilful exertion that the "Constitution" effected her escape from a position which for a time seemed desperate; but it should not escape attention that thus early in the war, before Great Britain had been able to re-enforce her American fleet, one of our frigates was unable to enter our principal seaport. "Finding the ship so far to the southward and eastward," reported Hull, "and the enemy's squadron stationed off New York, which would make it impossible to get in there, I determined to make for Boston, to receive your further orders."

On July 28 he writes from Boston that there were as yet no British cruisers in the Bay, nor off the New England coast; that great numbers of merchant vessels were daily arriving from Europe; and that he was warning them off the southern ports, advising that they should enter Boston. He reasoned that the enemy would now disperse, and probably send two frigates off the port. In this he under-estimated the deterrent effect of Rodgers' invisible command, but the apprehension hastened his own departure, and on August 2 he sailed again with the first fair wind. Running along the Maine coast to the Bay of Fundy, he thence went off Halifax; and meeting nothing there, in a three or four days' stay, moved to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, to intercept the trade of Canada and Nova Scotia. Here in the neighborhood of Cape Race some important captures were made, and on August 15 an American brig retaken, which gave information that Broke's squadron was not far away. This was probably a fairly correct report, as its returning course should have carried it near by a very few days before. Hull therefore determined to go to the southward, passing close to Bermuda, to cruise on the southern coast of the United States. In pursuance of this decision the "Constitution" had run some three hundred miles, when at 2 P.M. of August 19, being then nearly midway of the route over which Broke three weeks before had accompanied the convoy, a sail was sighted to the eastward, standing west. This proved to be the "Guerrière," on her return to Halifax, whither she was moving very leisurely, having traversed only two hundred miles in twelve days.

As the "Constitution," standing south-southwest for her destination, was crossing the "Guerrière's" bows, her course was changed, in order to learn the character of the stranger. By half-past three she was recognized to be a large frigate, under easy sail on the starboard tack; which, the wind being northwesterly, gives her heading from west-southwest to southwest. The "Constitution" was to windward. At 3.45 the "Guerrière," without changing her course, backed her maintopsail, the effect of which was to lessen her forward movement, leaving just way enough to keep command with her helm (G 1). To be thus nearly motionless assured the steadiest platform for aiming the guns, during the period most critical for the "Constitution," when, to get near, she must steer nearly head on, toward her opponent. The disadvantage of this approach is that the enemy's shot, if they hit, pass from end to end of the ship, a distance, in those days, nearly fourfold that of from side to side; and besides, the line from bow to stern was that on which the guns and the men who work them were ranged. The risks of grave injury were therefore greatly increased by exposure to this, which by soldiers is called enfilading, but at sea a raking fire; and to avoid such mischance was one of the principal concerns of a captain in a naval duel.

Seeing his enemy thus challenge him to come on, Hull, who had been carrying sail in order to close, now reduced his canvas to topsails, and put two reefs into them, bringing by the wind for that object (C 1). All other usual preparations were made at the same time; the "Constitution" during them lying side to wind, out of gunshot, practically motionless, like her antagonist. When all was ready, the ship kept away again, heading toward the starboard quarter of the British vessel; that is, she was on her right-hand side, steering toward her stern (C 2). As this, if continued, would permit her to pass close under the stern, and rake, Captain Dacres waited until he thought her within gunshot, when he fired the guns on the right-hand side of the vessel—the starboard broadside—and immediately wore ship; that is, turned the "Guerrière" round, making a half circle, and bringing her other side toward the "Constitution," to fire the other, or port, battery (G 2). It will be seen that, as both ships were moving in the same general direction, away from the wind, the American coming straight on, while the British retired by a succession of semicircles, each time this manœuvre was repeated the ships would be nearer together. This was what both captains purposed, but neither proposed to be raked in the operation. Hence, although the "Constitution" did not wear, she "yawed" several times; that is, turned her head from side to side, so that a shot striking would not have full raking effect, but angling across the decks would do proportionately less damage. Such methods were common to all actions between single ships.

These proceedings had lasted about three quarters of an hour, when Dacres, considering he now could safely afford to let his enemy close, settled his ship on a course nearly before the wind, having it a little on her left side (G 3). The American frigate was thus behind her, receiving the shot of her stern guns, to which the bow fire of those days could make little effective reply. To relieve this disadvantage, by shortening its duration, a big additional sail—the main topgallantsail—was set upon the "Constitution," which, gathering fresh speed, drew up on the left-hand side of the "Guerrière," within pistol-shot, at 6 P.M., when the battle proper fairly began (3). For the moment manœuvring ceased, and a square set-to at the guns followed, the ships running side by side. In twenty minutes the "Guerrière's" mizzen-mast430 was shot away, falling overboard on the starboard side; while at nearly the same moment, so Hull reported, her main-yard went in the slings.431 This double accident reduced her speed; but in addition the mast with all its hamper, dragging in the water on one side, both slowed the vessel and acted as a rudder to turn her head to starboard,—from the "Constitution." The sail-power of the latter being unimpaired would have quickly carried her so far ahead that her guns would no longer bear, if she continued the same course. Hull, therefore, as soon as he saw the spars of his antagonist go overboard, put the helm to port, in order to "oblige him to do the same, or suffer himself to be raked by our getting across his bows."432 The fall of the "Guerrière's" mast effected what was desired by Hull, who continues: "On our helm being put to port the ship came to, and gave us an opportunity of pouring in upon his larboard bow several broadsides." The disabled state of the British frigate, and the promptness of the American captain, thus enabled the latter to take a raking position upon the port (larboard) bow of the enemy; that is, ahead, but on the left side (4).

PLAN OF THE ENGAGEMENT BETWEEN THE CONSTITUTION AND GUERRIÈRE

The "Constitution" ranged on very slowly across the "Guerrière's" bows, from left to right; her sails shaking in the wind, because the yards could not be braced, the braces having been shot away. From this commanding position she gave two raking broadsides, to which her opponent could reply only feebly from a few forward guns; then, the vessels being close together, and the British forging slowly ahead, threatening to cross the American's stern, the helm of the latter was put up. As the "Constitution" turned away, the bowsprit of the "Guerrière" lunged over her quarter-deck, and became entangled by her port mizzen-rigging; the result being that the two fell into the same line, the "Guerrière" astern and fastened to her antagonist as described. (5) In her crippled condition for manœuvring, it was possible that the British captain might seek to retrieve the fortunes of the day by boarding, for which the present situation seemed to offer some opportunity; and from the reports of the respective officers it is clear that the same thought occurred to both parties, prompting in each the movement to repel boarders rather than to board. A number of men clustered on either side at the point of contact, and here, by musketry fire, occurred some of the severest losses. The first lieutenant and sailing-master of the "Constitution" fell wounded, and the senior officer of marines dead, shot through the head. All these were specially concerned where boarding was at issue. This period was brief; for at 6.30 the fore and main-masts of the British frigate gave way together, carrying with them all the head booms, and she lay a helpless hulk in the trough of a heavy sea, rolling the muzzles of her guns under. A sturdy attempt to get her under control with the spritsail433 was made; but this resource, a bare possibility to a dismasted ship in a fleet action, with friends around, was only the assertion of a sound never-give-up tradition, against hopeless odds, in a naval duel with a full-sparred antagonist. The "Constitution" hauled off for half an hour to repair damages, and upon returning received the "Guerrière's" surrender. It was then dark, and the night was passed in transferring the prisoners. When day broke, the prize was found so shattered that it would be impossible to bring her into port. She was consequently set on fire at 3 P.M., and soon after blew up.

In this fight the American frigate was much superior in force to her antagonist. The customary, and upon the whole justest, mode of estimating relative power, was by aggregate weight of shot discharged in one broadside; and when, as in this case, the range is so close that every gun comes into play, it is perhaps a useless refinement to insist on qualifying considerations. The broadside of the "Constitution" weighed 736 pounds, that of the "Guerrière" 570. The difference therefore in favor of the American vessel was thirty per cent, and the disparity in numbers of the crews was even greater. It is not possible, therefore, to insist upon any singular credit, in the mere fact that under such odds victory falls to the heavier vessel. What can be said, after a careful comparison of the several reports, is that the American ship was fought warily and boldly, that her gunnery was excellent, that the instant advantage taken of the enemy's mizzen-mast falling showed high seamanlike qualities, both in promptness and accuracy of execution; in short, that, considering the capacity of the American captain as evidenced by his action, and the odds in his favor, nothing could be more misplaced than Captain Dacres' vaunt before the Court: "I am so well aware that the success of my opponent was owing to fortune, that it is my earnest wish to be once more opposed to the 'Constitution,' with the same officers and crew under my command, in a frigate of similar force to the 'Guerrière.'"434 In view of the difference of broadside weight, this amounts to saying that the capacity and courage of the captain and ship's company of the "Guerrière," being over thirty per cent greater than those of the "Constitution," would more than compensate for the latter's bare thirty per cent superiority of force. It may safely be said that one will look in vain through the accounts of the transaction for any ground for such assumption. A ready acquiescence in this opinion was elicited, indeed, from two witnesses, the master and a master's mate, based upon a supposed superiority of fire, which the latter estimated to be in point of rapidity as four broadsides to every three of the "Constitution."435 But rapidity is not the only element of superiority; and Dacres' satisfaction on this score, repeatedly expressed, might have been tempered by one of the facts he alleged in defence of his surrender—that "on the larboard side of the 'Guerrière' there were about thirty shot which had taken effect about five sheets of copper down,"—far below the water-line.

Captain Hull with the "Constitution" reached Boston August 30, just four weeks after his departure; and the following day Commodore Rodgers with his squadron entered the harbor. It was a meeting between disappointment and exultation; for so profound was the impression prevailing in the United States, and not least in New England, concerning the irreversible superiority of Great Britain on the sea, that no word less strong than "exultation" can do justice to the feeling aroused by Hull's victory. Sight was lost of the disparity of force, and the pride of the country fixed, not upon those points which the attentive seaman can recognize as giving warrant for confidence, but upon the supposed demonstration of superiority in equal combat.

Consolation was needed; for since Rodgers' sailing much had occurred to dishearten and little to encourage. The nation had cherished few expectations from its tiny, navy; but concerning its arms on land the advocates of war had entertained the unreasoning confidence of those who expect to reap without taking the trouble to sow. In the first year of President Jefferson's administration, 1801, the "peace establishment" of the regular army, in pursuance of the policy of the President and party in power, was reduced to three thousand men. In 1808, under the excitement of the outrage upon the "Chesapeake" and of the Orders in Council, an "additional military force" was authorized, raising the total to ten thousand. The latter measure seems for some time to have been considered temporary in character; for in a return to Congress in January, 1810, the numbers actually in service are reported separately, as 2,765 and 4,189; total, 6,954, exclusive of staff officers.

General Scott, who was one of the captains appointed under the Act of 1808, has recorded that the condition of both soldiers and officers was in great part most inefficient.436 Speaking of the later commissions, he said, "Such were the results of Mr. Jefferson's low estimate of, or rather contempt for, the military character, the consequence of the old hostility between him and the principal officers who achieved our independence."437 In January, 1812, when war had in effect been determined upon in the party councils, a bill was passed raising the army to thirty-five thousand; but in the economical and social condition of the period the service was under a popular disfavor, to which the attitude of recent administrations doubtless contributed greatly, and recruiting went on very slowly. There was substantially no military tradition in the country. Thirty years of peace had seen the disappearance of the officers whom the War of Independence had left in their prime; and the Government fell into that most facile of mistakes, the choice of old men, because when youths they had worn an epaulette, without regarding the experience they had had under it, or since it was laid aside.