полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 1

"At the commencement of the war," wrote Monroe to Jefferson, "I was decidedly of your opinion, that the best disposition which could be made of our little navy would be to keep it in a body in a safe port, from which it might sally, only on some important occasion, to render essential service. Its safety, in itself, appeared an important object; as, while safe, it formed a check on the enemy in all operations along our coast, and increased proportionately his expense, in the force to be kept up, as well to annoy our commerce as to protect his own. The reasoning against this, in which all naval officers have agreed, is that, if stationed together in a port,—New York, for example,—the British would immediately block up this, by a force rather superior, and then harass our coast and commerce, without restraint, and with any force, however small. In that case a single frigate might, by cruising along the coast, and menacing continually different parts, keep in motion great bodies of militia; that, while our frigates are at sea, the expectation that they may be met together will compel the British to keep in a body, whenever they institute a blockade or cruise, a force equal at least to our own whole force; that they, [the American vessels] being the best sailors, hazard little by cruising separately, or together occasionally, as they might bring on an action, or avoid one, as they saw fit; that in that measure they would annoy the enemy's commerce wherever they went, excite alarm in the West Indies and elsewhere, and even give protection to our own trade by drawing the enemy's squadron from our own coast.... The reasoning in favor of each plan is so nearly equal that it is hard to say which is best."389 It is to be hoped that the sequel will show which was best, although little can be hoped when means, military and naval, have been allowed to waste as they had under the essentially unmilitary Administrations since 1801.

On November 25, 1811, seven months before the war began, the Secretary of the Treasury, Gallatin, communicated to the Senate a report on the State of the Finances,390 in which he showed that since 1801, by economies which totally crippled the war power of the nation, the public debt had been diminished from $80,000,000 to $34,000,000,—a saving of $46,000,000, which lessened the annual interest on the debt by $2,000,000. A good financial showing, doubtless; but, had there been on hand the troops and the ships, which the saved money represented, the War of 1812 might have had an issue more satisfactory to national retrospect. Gallatin also showed, in this paper, that by the restrictive system, enforced against Great Britain in consequence of the Administration's decision that Napoleon's revocation of his Decrees was real, the revenue had dropped from $12,000,000 to $6,000,000; leaving the nation with a probable deficiency of $2,000,000, on the estimate of a year of peace for 1812.

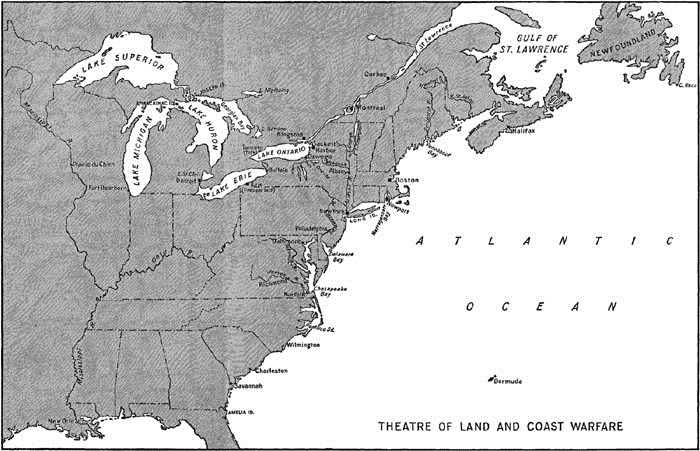

THEATRE OF LAND AND COAST WARFARE

CHAPTER V

THE THEATRE OF OPERATIONS

War being now immediately at hand, it is advisable, for the better appreciation of the course of events, the more accurate estimate of their historical and military value, to consider the relative conditions of the two opponents, the probable seats of warlike operations, and the methods which it was open to either to pursue.

Invasion of the British Islands, or of any transmarine possession of Great Britain—save Canada—was denied to the United States by the immeasurable inferiority of her navy. To cross the sea in force was impossible, even for short distances. For this reason, land operations were limited to the North American Continent. This fact, conjoined with the strong traditional desire, received from the old French wars and cherished in the War of Independence, to incorporate the Canadian colonies with the Union, determined an aggressive policy by the United States on the northern frontier. This was indeed the only distinctively offensive operation available to her upon the land; consequently it was imposed by reasons of both political and military expediency. On the other hand, the sea was open to American armed ships, though under certain very obvious restrictions; that is to say, subject to the primary difficulty of evading blockades of the coast, and of escaping subsequent capture by the very great number of British cruisers, which watched all seas where British commerce went and came, and most of the ports whence hostile ships might issue to prey upon it. The principal trammel which now rests upon the movements of vessels destined to cripple an enemy's commerce—the necessity to renew the motive power, coal, at frequent brief intervals—did not then exist. The wind, upon which motion depended, might at particular moments favor one of two antagonists relatively to the other; but in the long run it was substantially the same for all. In this respect all were on an equal footing; and the supply, if fickle at times, was practically inexhaustible. Barring accidents, vessels were able to keep the sea as long as their provisions and water lasted. This period may be reckoned as generally three months, while by watchful administration it might at times be protracted to six.

It is desirable to explain here what was, and is, the particular specific utility of operations directed toward the destruction of an enemy's commerce; what its bearing upon the issues of war; and how, also, it affects the relative interests of antagonists, unequally paired in the matter of sea power. Without attempting to determine precisely the relative importance of internal and external commerce, which varies with each country, and admitting that the length of transportation entails a distinct element of increased cost upon the articles transported, it is nevertheless safe to say that, to nations having free access to the sea, the export and import trade is a very large factor in national prosperity and comfort. At the very least, it increases by so much the aggregate of commercial transactions, while the ease and copiousness of water carriage go far to compensate for the increase of distance. Furthermore, the public revenue of maritime states is largely derived from duties on imports. Hence arises, therefore, a large source of wealth, of money; and money—ready money or substantial credit—is proverbially the sinews of war, as the War of 1812 was amply to demonstrate. Inconvertible assets, as business men know, are a very inefficacious form of wealth in tight times; and war is always a tight time for a country, a time in which its positive wealth, in the shape of every kind of produce, is of little use, unless by freedom of exchange it can be converted into cash for governmental expenses. To this sea-commerce greatly contributes, and the extreme embarrassment under which the United States as a nation labored in 1814 was mainly due to commercial exclusion from the sea. To attack the commerce of the enemy is therefore to cripple him, in the measure of success achieved, in the particular factor which is vital to the maintenance of war. Moreover, in the complicated conditions of mercantile activity no one branch can be seriously injured without involving others.

This may be called the financial and political effect of "commerce destroying," as the modern phrase runs. In military effect, it is strictly analogous to the impairing of an enemy's communications, of the line of supplies connecting an army with its base of operations, upon the maintenance of which the life of the army depends. Money, credit, is the life of war; lessen it, and vigor flags; destroy it, and resistance dies. No resource then remains except to "make war support war;" that is, to make the vanquished pay the bills for the maintenance of the army which has crushed him, or which is proceeding to crush whatever opposition is left alive. This, by the extraction of private money, and of supplies for the use of his troops, from the country in which he was fighting, was the method of Napoleon, than whom no man held more delicate views concerning the gross impropriety of capturing private property at sea, whither his power did not extend. Yet this, in effect, is simply another method of forcing the enemy to surrender a large part of his means, so weakening him, while transferring it to the victor for the better propagation of hostilities. The exaction of a pecuniary indemnity from the worsted party at the conclusion of a war, as is frequently done, differs from the seizure of property in transit afloat only in method, and as peace differs from war. In either case, money or money's worth is exacted; but when peace supervenes, the method of collection is left to the Government of the country, in pursuance of its powers of taxation, to distribute the burden among the people; whereas in war, the primary object being immediate injury to the enemy's fighting power, it is not only legitimate in principle, but particularly effective, to seek the disorganization of his financial system by a crushing attack upon one of its important factors, because effort thus is concentrated on a readily accessible, fundamental element of his general prosperity. That the loss falls directly on individuals, or a class, instead of upon the whole community, is but an incident of war, just as some men are killed and others not. Indirectly, but none the less surely, the whole community, and, what is more important, the organized government, are crippled; offensive powers impaired.

But while this is the absolute tendency of war against commerce, common to all cases, the relative value varies greatly with the countries having recourse to it. It is a species of hostilities easily extemporized by a great maritime nation; it therefore favors one whose policy is not to maintain a large naval establishment. It opens a field for a sea militia force, requiring little antecedent military training. Again, it is a logical military reply to commercial blockade, which is the most systematic, regularized, and extensive form of commerce-destruction known to war. Commercial blockade is not to be confounded with the military measure of confining a body of hostile ships of war to their harbor, by stationing before it a competent force. It is directed against merchant vessels, and is not a military operation in the narrowest sense, in that it does not necessarily involve fighting, nor propose the capture of the blockaded harbor. It is not usually directed against military ports, unless these happen to be also centres of commerce. Its object, which was the paramount function of the United States Navy during the Civil War, dealing probably the most decisive blow inflicted upon the Confederacy, is the destruction of commerce by closing the ports of egress and ingress. Incidental to that, all ships, neutrals included, attempting to enter or depart, after public notification through customary channels, are captured and confiscated as remorselessly as could be done by the most greedy privateer. Thus constituted, the operation receives far wider scope than commerce-destruction on the high seas; for this is confined to merchantmen of belligerents, while commercial blockade, by universal consent, subjects to capture neutrals who attempt to infringe it, because, by attempting to defeat the efforts of one belligerent, they make themselves parties to the war.

In fact, commercial blockade, though most effective as a military measure in broad results, is so distinctly commerce-destructive in essence, that those who censure the one form must logically proceed to denounce the other. This, as has been seen,391 Napoleon did; alleging in his Berlin Decree, in 1806, that war cannot be extended to any private property whatever, and that the right of blockade is restricted to fortified places, actually invested by competent forces. This he had the face to assert, at the very moment when he was compelling every vanquished state to extract, from the private means of its subjects, coin running up to hundreds of millions to replenish his military chest for further extension of hostilities. Had this dictum been accepted international law in 1861, the United States could not have closed the ports of the Confederacy, the commerce of which would have proceeded unmolested; and hostile measures being consequently directed against men's persons instead of their trade, victory, if accomplished at all, would have cost three lives for every two actually lost. It is apparent, immediately on statement, that against commerce-destruction by blockade, the recourse of the weaker maritime belligerent is commerce-destruction by cruisers on the high sea. Granting equal efficiency in the use of either measure, it is further plain that the latter is intrinsically far less efficacious. To cut off access to a city is much more certainly accomplished by holding the gates than by scouring the country in search of persons seeking to enter. Still, one can but do what one can. In 1861 to 1865, the Southern Confederacy, unable to shake off the death grip fastened on its throat, attempted counteraction by means of the "Alabama," "Sumter," and their less famous consorts, with what disastrous influence upon the navigation—the shipping—of the Union it is needless to insist. But while the shipping of the opposite belligerent was in this way not only crippled, but indirectly was swept from the seas, the Confederate cruisers, not being able to establish a blockade, could not prevent neutral vessels from carrying on the commerce of the Union. This consequently suffered no serious interruption; whereas the produce of the South, its inconvertible wealth—cotton chiefly—was practically useless to sustain the financial system and credit of the people. So, in 1812 and the two years following, the United States flooded the seas with privateers, producing an effect upon British commerce which, though inconclusive singly, doubtless co-operated powerfully with other motives to dispose the enemy to liberal terms of peace. It was the reply, and the only possible reply, to the commercial blockade, the grinding efficacy of which it will be a principal object of these pages to depict. The issue to us has been accurately characterized by Mr. Henry Adams, in the single word "Exhaustion."392

Both parties to the War of 1812 being conspicuously maritime in disposition and occupation, while separated by three thousand miles of ocean, the sea and its navigable approaches became necessarily the most extensive scene of operations. There being between them great inequality of organized naval strength and of pecuniary resources, they inevitably resorted, according to their respective force, to one or the other form of maritime hostilities against commerce which have been indicated. To this procedure combats on the high seas were merely incidental. Tradition, professional pride, and the combative spirit inherent in both peoples, compelled fighting when armed vessels of nearly equal strength met; but such contests, though wholly laudable from the naval standpoint, which under ordinary circumstances cannot afford to encourage retreat from an equal foe, were indecisive of general results, however meritorious in particular execution. They had no effect upon the issue, except so far as they inspired moral enthusiasm and confidence. Still more, in the sequel they have had a distinctly injurious effect upon national opinion in the United States. In the brilliant exhibition of enterprise, professional skill, and usual success, by its naval officers and seamen, the country has forgotten the precedent neglect of several administrations to constitute the navy as strong in proportion to the means of the country as it was excellent through the spirit and acquirements of its officers. Sight also has been lost of the actual conditions of repression, confinement, and isolation, enforced upon the maritime frontier during the greater part of the war, with the misery and mortification thence ensuing. It has been widely inferred that the maritime conditions in general were highly flattering to national pride, and that a future emergency could be confronted with the same supposed facility, and as little preparation, as the odds of 1812 are believed to have been encountered and overcome. This mental impression, this picture, is false throughout, alike in its grouping of incidents, in its disregard of proportion, and in its ignoring of facts. The truth of this assertion will appear in due course of this narrative, and it will be seen that, although relieved by many brilliant incidents, indicative of the real spirit and capacity of the nation, the record upon the whole is one of gloom, disaster, and governmental incompetence, resulting from lack of national preparation, due to the obstinate and blind prepossessions of the Government, and, in part, of the people.

This was so even upon the water, despite the great names—for great they were in measure of their opportunities—of Decatur, Hull, Perry, Macdonough, Morris, and a dozen others. On shore things were far worse; for while upon the water the country had as leaders men still in the young prime of life, who were both seamen and officers,—none of those just named were then over forty,—the army at the beginning had only elderly men, who, if they ever had been soldiers in any truer sense than young fighting men,—soldiers by training and understanding,—had long since disacquired whatever knowledge and habit of the profession they had gained in the War of Independence, then more than thirty years past. "As far as American movements are concerned," said one of Wellington's trusted officers, sent to report upon the subject of Canadian defence, "the campaign of 1812 is almost beneath criticism."393 Instructed American opinion must sorrowfully admit the truth of the comment. That of 1813 was not much better, although some younger men—Brown, Scott, Gaines, Macomb, Ripley—were beginning to show their mettle, and there had by then been placed at the head of the War Department a secretary who at least possessed a reasoned understanding of the principles of warfare. With every material military advantage, save the vital one of adequate preparation, it was found too late to prepare when war was already at hand; and after the old inefficients had been given a chance to demonstrate their incapacity, it was too late to utilize the young men.

Jefferson, with curious insanity of optimism, had once written, "We begin to broach the idea that we consider the whole Gulf Stream as of our waters, within which hostilities and cruising are to be frowned on for the present, and prohibited as soon as either consent or force will permit;"394 while at the same time, under an unbroken succession of maritime humiliations, he of purpose neglected all naval preparation save that of two hundred gunboats, which could not venture out of sight of land without putting their guns in the hold. With like blindness to the conditions to which his administration had reduced the nation, he now wrote: "The acquisition of Canada this year [1812], as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching."395 This would scarcely have been a misappreciation, had his care for the army and that of his successor given the country in 1812 an effective force of fifteen thousand regulars. Great Britain had but forty-five hundred in all Canada,396 from Quebec to St. Joseph's, near Mackinac; and the American resources in militia were to hers as ten to one. But Jefferson and Madison, with their Secretary of the Treasury, had reduced the national debt between 1801 and 1812 from $80,000,000 to $45,000,000, concerning which a Virginia Senator remarked: "This difference has never been felt by society. It has produced no effect upon the common intercourse among men. For my part, I should never have known of the reduction but for the annual Treasury Report."397 Something was learned about it, however, in the first year of the war, and the interest upon the savings was received at Detroit, on the Niagara frontier, in the Chesapeake and the Delaware.

The War of 1812 was very unpopular in certain sections of the United States and with certain parts of the community. By these, particular fault was found with the invasion of Canada. "You have declared war, it was said, for two principal alleged reasons: one, the general policy of the British Government, formulated in the successive Orders in Council, to the unjustifiable injury and violation of American commerce; the other, the impressment of seamen from American merchant ships. What have Canada and the Canadians to do with either? If war you must, carry on your war upon the ocean, the scene of your avowed wrongs, and the seat of your adversary's prosperity, and do not embroil these innocent regions and people in the common ruin which, without adequate cause, you are bringing upon your own countrymen, and upon the only nation that now upholds the freedom of mankind against that oppressor of our race, that incarnation of all despotism—Napoleon." So, not without some alloy of self-interest, the question presented itself to New England, and so New England presented it to the Government and the Southern part of the Union; partly as a matter of honest conviction, partly as an incident of the factiousness inherent in all political opposition, which makes a point wherever it can.

Logically, there may at first appear some reason in these arguments. We are bound to believe so, for we cannot entirely impeach the candor of our ancestors, who doubtless advanced them with some degree of conviction. The answer, of course, is, that when two nations go to war, all the citizens of one become internationally the enemies of the other. This is the accepted principle of International Law, a residuum of the concentrated wisdom of many generations of international legists. When war takes the place of peace, it annihilates all natural and conventional rights, all treaties and compacts, except those which appertain to the state of war itself. The warfare of modern civilization assures many rights to an enemy, by custom, by precedent, by compact; many treaties bear express stipulations that, should war arise between the parties, such and such methods of warfare are barred; but all these are merely guaranteed exceptions to the general rule that every individual of each nation is the enemy of those of the opposing belligerent.

Canada and the Canadians, being British subjects, became therefore, however involuntarily, the enemies of the United States, when the latter decided that the injuries received from Great Britain compelled recourse to the sword. Moreover, war, once determined, must be waged on the principles of war; and whatever greed of annexation may have entered into the motives of the Administration of the day, there can be no question that politically and militarily, as a war measure, the invasion of Canada was not only justifiable but imperative. "In case of war," wrote the United States Secretary of State, Monroe, a very few days398 before the declaration, "it might be necessary to invade Canada; not as an object of the war, but as a means to bring it to a satisfactory conclusion." War now is never waged for the sake of mere fighting, simply to see who is the better at killing people. The warfare of civilized nations is for the purpose of accomplishing an object, obtaining a concession of alleged right from an enemy who has proved implacable to argument. He is to be made to yield to force what he has refused to reason; and to do that, hold is laid upon what is his, either by taking actual possession, or by preventing his utilizing what he still may retain. An attachment is issued, so to say, or an injunction laid, according to circumstances; as men in law do to enforce payment of a debt, or abatement of an injury. If, in the attempt to do this, the other nation resists, as it probably will, then fighting ensues; but that fighting is only an incident of war. War, in substance, though not perhaps in form, began when the one nation resorted to force, quite irrespective of the resistance of the other.

Canada, conquered by the United States, would therefore have been a piece of British property attached; either in compensation for claims, or as an asset in the bargaining which precedes a treaty of peace. Its retention even, as a permanent possession, would have been justified by the law of war, if the military situation supported that course. This is a political consideration; militarily, the reasons were even stronger. To Americans the War of 1812 has worn the appearance of a maritime contest. This is both natural and just; for, as a matter of fact, not only were the maritime operations more pleasing to retrospect, but they also were as a whole, and on both sides, far more efficient, far more virile, than those on land. Under the relative conditions of the parties, however, it ought to have been a land war, because of the vastly superior advantages on shore possessed by the party declaring war; and such it would have been, doubtless, but for the amazing incompetency of most of the army leaders on both sides, after the fall of the British general, Brock, almost at the opening of hostilities. This incompetency, on the part of the United States, is directly attributable to the policy of Jefferson and Madison; for had proper attention and development been given to the army between 1801 and 1812, it could scarcely have failed that some indication of men's fitness or unfitness would have preceded and obviated the lamentable experience of the first two years, when every opportunity was favorable, only to be thrown away from lack of leadership. That even the defects of preparation, extreme and culpable as these were, could have been overcome, is evidenced by the history of the Lakes. The Governor General, Prevost, reported to the home government in July and August, 1812, that the British still had the naval superiority on Erie and Ontario;399 but this condition was reversed by the energy and capacity of the American commanders, Chauncey, Perry, and Macdonough, utilizing the undeniable superiority in available resources—mechanics and transportation—which their territory had over the Canadian, not for naval warfare only, but for land as well.