полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire 1793-1812, vol I

There was, however, one radical fallacy underlying Bonaparte's Egyptian, or rather Oriental, expedition,—for in his mind it far outleaped the narrow limits of the Nile valley,—and that lay in the effect he expected to produce upon Great Britain. It is all very well to stigmatize, after Lanfrey's fashion, as the vagaries of a distempered fancy, the vast projects of Eastern conquest and dominion, which unquestionably filled his mind with dreams of a sweep to his arms rivalling that of Alexander and of the Roman legions. An extraordinary, perhaps even an extravagant, imagination was one of the necessary conditions of Napoleon's wonderful career. That it should from time to time lead him into great mistakes, and ultimately to his ruin, was perhaps inevitable. Without it, or with it in a markedly less degree, he might have died in his palace an old man and left his throne to a son, if not to a dynasty; but also without it he would not have produced upon his own age and upon all subsequent history the effects which he has left. To it were due the Oriental visions, to which, regarded as a military enterprise, the present writer is certainly not ready to apply the word "fantastic." But, as a blow directed against Great Britain, there was in them a fatal defect of conception, due more to a miscalculation of the intellect, a prejudice of his day, than to a wild flight of fancy.

In the relations of India to Great Britain, Bonaparte, in common with all Frenchmen of his age, mistook effect for cause. The possession of India and of other colonies was to them the cause of British prosperity; just as at a later time, and now, the wide extent of British commerce has seemed to many the cause of Great Britain's wealth and eminence among the nations. That there is truth in this view is not to be denied; but it is the kind of truth compatible with putting the cart before the horse, mistaking the fruit for the tree, the flower for the plant. There was less excuse for a blunder of this kind in a quick-witted nation like the French, for they had before their eyes the fact that they had long owned some of the richest colonies in the world; and yet the British had, upon their own ground, amid all disadvantages of position, absorbed the commerce of the West Indies, French as well as Spanish. In local advantages, Great Britain in the West Indies had not the tenth of what France and Spain had; yet she so drank the wealth of the region that one fourth of her envied commerce then depended upon it. So in India; Great Britain sucked the wealth of India, because of the energy and commercial genius of her people. Had Bonaparte's visions been realized and India dominated, Great Britain would not have been overcome. A splendid bough would have been torn from a tree, and, in falling, would have carried to the ground the fruit depending from it; but not only was the amount of the fruit exaggerated, but the recuperative power of the root, the aptitude of the great trunk to throw out new branches, was not understood. Had Bonaparte converted the rule of India from England to France, he would have embarrassed, not destroyed, British traffic therein. Like the banyan tree, a new sucker would have been thrown out and reached the soil in some new spot, defying efforts at repression; as British commerce later refused to die under the far more searching efforts of the Continental System.

The strength of Great Britain could be said to lie in her commerce only as, and because, it was the external manifestation of the wisdom and strength of the British people, unhampered by any control beyond that of a government and institutions in essential sympathy with them. In the enjoyment of these blessings,—in their independence and untrammelled pursuit of wealth,—they were secured by their powerful navy; and so long as this breastplate was borne, unpierced, over the heart of the great organism, over the British islands themselves, Great Britain was—not invulnerable—but invincible. She could be hurt indeed, but she could not be slain. Herein was Bonaparte's error. His attempt upon India was strategically a fine conception; it was an attack upon the flank of an enemy whose centre was then too strong for him; but as a broad effort of military policy,—of statesmanship directing arms,—it was simply delivering blows upon an extremity, leaving the heart untouched. The same error pervaded his whole career; for, with all his genius, he still was, as Thiers has well said, the child of his century. So, in his later years, he was beguiled into the strife wherein he bruised Great Britain's heel, and she bruised his head. Yet his mistake, supreme genius that he was, is scarce to be wondered at; for after all the story of his career, of his huge power, of his unrelenting hostility, of his indomitable energy, unremittingly directed to the destruction of his chief enemy,—after all this and its failure,—we still find men harping on the weakness of Great Britain through her exposed commerce. Her dependence upon trade, and the apparent slackening of the colonial ties, foretell her fatal weakness in the hour of trial. So thought Napoleon; so think we. Yet the commercial genius of her people is not abated; and the most fruitful parts of that colonial system existed scarcely, if at all, in those old days, when her commerce was as great in proportion to her numbers as it is now. To paralyze this, it must be taken by the throat; no snapping at the heels will do it. To command the sea approaches to the British islands will be to destroy the power of the State; as a preliminary thereto the British navy must be neutralized by superior numbers, or by superior skill.

Like the furtive intrusion and hasty retreat of Bruix's fleet, the stealthy manner of Bonaparte's return to Europe proclaimed the control of the Mediterranean by the British navy, and foretold the certain fall of his two great conquests, Egypt and Malta. His own personal credit was too deeply staked upon their deliverance, both by his original responsibility for the expedition and by the promises of succor made to the soldiers abandoned in Egypt, to admit a doubt of his wish to save them, if it could be done. His correspondence is full of the subject, and numerous efforts were made; as great, probably, as were permitted by the desperate struggle with external enemies and internal disorder in which he found France plunged. All, however, proved fruitless. The detailed stories of the loss of Egypt and of Malta by France have much interest, both for the military and unprofessional reader; but they are summed up in the one fact which prophesied their fall: France had lost all power to dispute the control of the sea. From February, 1799, when a small frigate entered La Valetta, to January, 1800, not a vessel reached the port. In the latter month a dispatch-boat got in, bringing news of Bonaparte's accession to power as First Consul; which event, though two months old, was still unknown to the garrison. On the 6th of February Admiral Perrée, who had served on the Nile and in Syria to Bonaparte's great satisfaction, sailed from Toulon with the "Généreux," seventy-four, one of the ships that had escaped from Aboukir Bay, three smaller vessels, and one large transport. A quantity of supplies and between three and four thousand troops for the relief of Malta were embarked in the squadron. On the 18th they fell in with several British ships, under Nelson's immediate command; and after the exchange of a few shots, one of which killed Perrée, the "Généreux" and the transport struck to a force too superior to be resisted. The other ships returned to Toulon.

All further attempts to introduce relief likewise failed. During the two years' blockade, from September, 1798, to September, 1800, only five vessels succeeded in entering the port. 297 The "Guillaume Tell," which had lain in Valetta harbor since the battle of the Nile, attempted to escape on the night of the 31st of March, being charged with letters to Bonaparte saying that the place could not hold out longer than June. The ship was intercepted by the British, and surrendered after a brilliant fight, in which all her masts were shot away 298 and over a fifth of her crew killed and wounded. One of the vessels sharing in this capture was Lord Nelson's flag-ship, the "Foudroyant," but the admiral himself was not on board. Swayed by a variety of feelings, to analyze which is unnecessary and not altogether pleasant to those who admire his fame, he had asked, after the return of Lord Keith, to be relieved and granted a repose to which his long and brilliant services assuredly entitled him. He thus failed to receive the surrender of the last of the ships which escaped from the Nile, and to accomplish the reduction of Malta, whose ultimate fate had been determined by his previous career of victory. The island held out until the 5th of September, 1800. Nelson on the 11th of July struck his flag in Leghorn, and in company with the Hamiltons went home overland, by way of Trieste and Vienna, reaching England in November.

The story of Egypt is longer and its surrender was later,—due also to force, not to starvation. An army powerful enough to hold in submission and reap the use of the fertile valley of the Nile, could never be reduced like the port of a rocky island, blocked by sea and surrounded by a people in successful insurrection. Nevertheless, the same cause that determined the loss of Malta operated effectually to make Egypt a worse than barren possession.

Bonaparte, though wielding uncontrolled sway over all the resources of France, found as great difficulty in getting news from his conquest or substantial succor to it as he had had, when in Egypt, to obtain intelligence from home. Unwearying official effort and lavish inducements to private enterprise alike proved vain. In the first week of September, 1800, the return of the "Osiris," a dispatch-boat that had successfully made the round voyage between France and Egypt, was rewarded by a gift of three thousand dollars to the captain and two months' pay to the crew. This extravagant recompense sufficiently testifies the difficulty of the feat; and over seven weeks later, on October 29, Bonaparte writes to Menou, "We have no direct news of you since the arrival of the 'Osiris.'" This letter was to be entrusted to Admiral Ganteaume; but three months elapsed before that officer was enabled by a violent gale to evade the British blockade of Brest. Appeals were made to Spain, and government agents sent throughout the south of France, as well as to Corsica, to Genoa, to Leghorn, to the Adriatic, to Taranto, when Italy after Marengo again fell under Bonaparte's control. Numerous small vessels, both neutral and friendly, were from every quarter to start for Egypt, if by chance some of them might reach their destination; but no substantial result followed. For the most part they only swelled the list of captures, and attested the absolute control of the sea by Great Britain.

Kleber, the illustrious general to whom Bonaparte left the burden he himself dropped, in a letter which fell into the hands of the British, addressed to the Directory the following words: 299 "I know all the importance of the possession of Egypt. I used to say in Europe that this country was for France the fulcrum, by means of which she might move at will the commercial system of every quarter of the globe; but to do this effectually, a powerful lever is required, and that lever is a Navy. Ours has ceased to exist. Since that period everything has changed; and peace with the Porte is, in my opinion, the only expedient that holds out to us a method of fairly getting rid of an enterprise no longer capable of attaining the object for which it was undertaken." 300 In other words, the French force of admirable and veteran soldiers in Egypt was uselessly locked up there; being unable either to escape or to receive re-enforcement, they were lost to their country. So thought Nelson, who frequently declared in his own vehement fashion that not one should with his consent return to Europe, and who gave to Sir Sidney Smith most positive orders on no account to allow a single Frenchman to leave Egypt under passports. 301 So thought Bonaparte, despite the censure which he and his undiscriminating supporters have seen fit to pass upon Kleber. Six weeks before he sailed for Europe 302 he wrote to the Directory: "We need at least six thousand men to replace our losses since landing in Egypt.... With fifteen thousand re-enforcements we could go to Constantinople. We should need, then, two thousand cavalry, six thousand recruits for the regiments now here; five hundred artillerists; five hundred mechanics (carpenters, masons, etc.); five demi-brigades of two thousand men each; twenty thousand muskets, forty thousand bayonets, etc. etc. If you cannot send us all this assistance it will be necessary to make peace; for, between this and next June, we may expect to lose another six thousand men." 303 But how was this help to be sent when the sea was securely closed?

Bonaparte and Kleber held essentially the same view of the situation; but the one was interested, like a bankrupt, in concealing the state of affairs, the other was not. Kleber therefore gladly closed with a proposition, made by the Turks under the countenance of Sir Sidney Smith, who still remained in the Levant, by which the French were to be permitted to evacuate Egypt and to be carried to France; Turkey furnishing such transports as were needed beyond those already in Alexandria. A convention to this effect was signed at El Arish on the 24th of January, 1800, by commissioners representing Kleber on the one hand and the commander-in-chief of the Turks on the other. The French army would thus be restored to France, under no obligations that would prevent its at once entering the field against the allies of Great Britain and Turkey. Sir Sidney Smith did not sign; but it appears from his letter of March 8, 1800, 304 to M. Poussielgue, one of Kleber's commissioners, that he was perfectly cognizant of and approving the terms of an agreement in direct contravention of the treaty of alliance between Turkey and Great Britain, and containing an article (the eleventh) engaging his government to issue the passports and safe conducts for the return of the French, 305 which depended absolutely upon its control of the sea, and which his own orders from his superiors explicitly forbade.

The British government had meantime instructed Lord Keith that the French should not be allowed to leave Egypt, except as prisoners of war. On the 8th of January, over a fortnight before the convention of El Arish was signed, the admiral wrote from Port Mahon to notify Smith of these directions, which were identical in spirit with those he already had from Nelson. With this letter he enclosed one to Kleber, "to be made use of if circumstances should so require." This letter, cast in the peremptory tone probably needed to repress Smith, informed Kleber curtly that he had "received positive orders not to consent to any capitulation of the French troops, unless they should lay down their arms, surrender themselves prisoners of war, and deliver up the ships and stores in Alexandria." Even in this event they were not to be permitted to return to France until exchanged. The admiral added that any vessel with French troops on board, having passports "from others than those authorized to grant them," would be forced by British cruisers to return to Alexandria. 306 Smith, knowing that he had exceeded his authority, had nothing to do in face of this communication but to transmit the letters apologetically to Kleber, expressing the hope that the engagement allowed by him would ultimately be sustained. In this he was not deceived. The British cabinet, learning that Kleber had executed an essential part of his own agreements, under the impression that Smith had authority to pledge his government, sent other instructions to Keith, authorizing the carrying out of the convention while expressly denying Smith's right to accede to it. Owing to the length of time required in that age for these communications to pass back and forth, such action had been taken by Kleber, before these new instructions were received, that the convention never became operative. The French occupation lingered on. Kleber, being assassinated on the 14th of June, 1800, was succeeded by Menou, an incapable man; and in March, 1801, a British army under General Abercromby landed in Aboukir Bay. Abercromby was mortally wounded on the 21st, at the battle of Alexandria; but his successor was equal to the task before him, and in September, 1801, shortly before the preliminaries of peace with Great Britain were signed, the last of the French quitted Egypt.

The terms under which the evacuation was made were much the same as those granted at El Arish; but circumstances had very greatly changed. The battle of Marengo, June 14, 1800, and the treaty of Lunéville, February 9, 1801, had restored peace to the Continent; the French troops would not now re-enforce an enemy to the allies of Great Britain. Not only so, but since the power of Austria had been broken, Great Britain herself was intending a peace, to which the policy of Bonaparte at that time pointed. It was therefore important to her that in the negotiations the possession of Egypt, however barren, should not be one of the cards in the adversary's hand. No terms were then too easy, provided they insured the immediate departure of the French army.

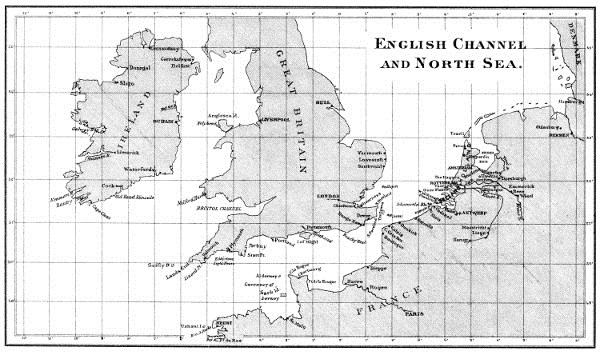

English Channel and North Sea.

CHAPTER XI

The Atlantic, 1796-1801.—The Brest Blockades.—The French Expeditions Against IrelandTHE decision taken by the French executive in the latter part of 1795,—after the disastrous partial encounters of Martin with Hotham in the Mediterranean and of Villaret Joyeuse with Bridport in the Bay of Biscay,—to discontinue sending large fleets to sea, and to rely upon commerce-destroying, by single cruisers or small squadrons, to reduce the strength of Great Britain, remained unchanged during the following years, and was adopted by Bonaparte when the Consular government, in 1799, succeeded that of the Directory. This policy was in strict accord with the general feeling of the French nation, as well naval officers as unprofessional men, by which the action of the navy was ever subordinated to other military considerations, to "ulterior objects," as the phrase commonly ran,—a feeling that could not fail to find favor and expression in the views of the great director of armies who ruled France during the first fourteen years of this century. It amounted, however, simply to abandoning all attempt to control the sea. Consequently, whenever any enterprise was undertaken which required this to be crossed, resort was necessarily had to evasion, more or less skilfully contrived; and success depended, not upon the reasonable certainty conferred by command of the water, by the skilful massing of forces, but upon a balance of chances, which might be more or less favorable in the particular instance, but could never be regarded as reaching the degree of security which is essential, even in the hazardous combinations of the game of war. This formal relegation of the navy to a wholly inferior place in the contest then raging, was followed, under the embarrassments of the treasury, by a neglect of the material of war, of the ships and their equipments, which left France still at Great Britain's mercy, even when in 1797 and 1798 her Continental enemies had been shaken off by the audacity and address of Bonaparte.

Thrice only, therefore, during the six years in question, ending with the Peace of Amiens in 1802, did large French fleets put to sea; and on each occasion their success was made to depend upon the absence of the British fleets, or upon baffling their vigilance. As in commerce-destroying, stealth and craft, not force, were the potent factors. Of the three efforts, two, Bonaparte's Egyptian expedition and Bruix's escape from Brest in 1799, have been already narrated under the head of the Mediterranean, to which they chiefly–the former wholly—belong. The third was the expedition against Ireland, under the command of Hoche, to convoy which seventeen ships-of-the-line and twenty smaller vessels sailed from Brest in the last days of 1796.

The operations in the Atlantic during this period were accordingly, with few exceptions, reduced to the destruction of commerce, to the harassment of the enemy's communications on the sea, and, on the part of the British, to an observation, more or less vigilant, of the proceedings in the enemy's naval ports, of which Brest was the most important. From the maritime conditions of the two chief belligerents, the character of their undertakings differed. British commerce covered every sea and drew upon all quarters of the world; consequently French cruisers could go in many directions upon the well known commercial routes, with good hope of taking prizes, if not themselves captured. British cruisers, on the other hand, could find French merchant vessels only on their own coast, for the foreign traffic of France in ships of her own was destroyed; but the coasting trade, carried on in vessels generally of from thirty to a hundred tons, was large, and in the maritime provinces took in great measure the place of land carriage. The neutrals who maintained such foreign trade as was left to the enemies of Great Britain, and who were often liable to detention from some infraction, conscious or unconscious, of the rules of international law, were naturally to be found in greatest numbers in the neighborhood of the coasts to which they were bound. Finally, the larger proportion of French privateers were small vessels, intended to remain but a short time at sea and to cruise in the Channel or among its approaches, where British shipping most abounded. For all these reasons the British provided for the safety of their distant commerce by concentrating it in large bodies called convoys, each under the protection of several ships of war; while their scattered cruisers were distributed most thickly near home,—in the English Channel, between the south coast of Ireland and Ushant, in the waters of the bay of Biscay, and along the coasts of Spain and Portugal. There they were constantly at hand to repress commerce-destroying, to protect or recapture their own merchantmen, and to reduce the coasting trade of the enemy, as well as the ability of his merchants to carry on, under a neutral flag, the operations no longer open to their own. The annals of the time are consequently filled, not with naval battles, but with notes of vessels taken and retaken; of convoys, stealing along the coast of France, chased, harassed and driven ashore, by the omnipresent cruisers of the enemy. Nor was it commerce alone that was thus injured. The supplying of the naval ports, even with French products, chiefly depended upon the coasting vessels; and embarrassment, amounting often to disability, was constantly entailed by the unflagging industry of the hostile ships, whose action resembled that which is told of the Spanish guerillas, upon the convoys and communications of the French armies in the Peninsular War. 307

The watch over the enemy's ports, and particularly over the great and difficult port of Brest, was not, during the earlier and longer part of this period, maintained with the diligence nor with the force becoming a great military undertaking, by which means alone such an effort can be made effective in checking the combinations of an active opponent. Some palliation for this slack service may perhaps be found in the knowledge possessed by the admiralty of the condition of the French fleet and of the purposes of the French government, some also in the well-known opinions of that once active officer, Lord Howe; but even these circumstances can hardly be considered more than a palliation for a system essentially bad. The difficulties were certainly great, the service unusually arduous, and it was doubtless true that the closest watch could not claim a perfect immunity from evasion; but from what human efforts can absolute certainty of results be predicted? and above all, in war? The essential feature of the military problem, by which Great Britain was confronted, was that the hostile fleets were divided, by the necessities of their administration, among several ports. To use these scattered divisions successfully against her mighty sea power, it was needed to combine two or more of them in one large body. To prevent such a combination was therefore the momentous duty of the British fleet; and in no manner could this be so thoroughly carried out as by a close and diligent watch before the hostile arsenals,—not in the vain hope that no squadron could ever, by any means, slip out, but with the reasonable probability that at no one period could so many escape as to form a combination threatening the Empire with a crushing disaster. Of these arsenals Brest, by its situation and development, was the most important, and contained usually the largest and most efficient of the masses into which the enemies' fleets were divided. The watch over it, therefore, was of supreme consequence; and in the most serious naval crisis of the Napoleonic wars the Brest "blockading" fleet, as it was loosely but inaccurately styled, by the firmness of its grip broke up completely one of the greatest of Napoleon's combinations. To it, and to its admiral, Cornwallis, was in large measure due that the vast schemes which should have culminated in the invasion of England, by one hundred and fifty thousand of the soldiers who fought at Austerlitz and Jena, terminated instead in the disaster of Trafalgar. Yet it may be said that had there prevailed in 1805 the system with which the names of Howe and Bridport are identified, and which was countenanced by the Admiralty until the stern Earl St. Vincent took command, the chances are the French Brest fleet would have taken its place in the great strategic plan of the Emperor.