полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire 1793-1812, vol I

Bonaparte's rapid successes and wide flight of conquest materially affected the British fleet; and the question of supplies became very serious with the ports of Tuscany, Naples and the Pope closed to its aid. Growing symptoms of discontent made the tenure of Corsica doubtful, with the French in Leghorn, and with Genoa tolerating their intrigues through fear of their armies. As early as May 20, immediately after entering Milan, Bonaparte had sent agents to Genoa to concert risings in the island; and in July he began to collect in Leghorn a body of Corsican refugees, at whose head he put General Gentili, also a native. The threatening outlook of affairs, and the submission of Tuscany to the violation of her neutrality by the French, determined the viceroy of Corsica to seize Elba, although a Tuscan possession. Nelson, with a small squadron, appeared before Porto Ferrajo on the 10th of July, and to a peremptory summons received immediate surrender. Being very small, Elba was more immediately under naval control than Corsica, and to hold it required fewer troops. In case of the loss of the larger island, it would still assure the British a base in the Mediterranean and continued control, so long as their fleet could assert predominance over those of their enemies.

Some doubt, however, was felt on this latter point. The attitude of Spain, far from cordial when an ally, had been cold as a neutral, and was now fast becoming hostile. The decrepit kingdom had a navy of over fifty sail-of-the-line; and, although its discipline and efficiency were at the lowest ebb, the mere force of numbers might prove too much for even Jervis's splendid fleet of only twenty-two,—seven of which were still before Cadiz, a thousand miles from the main body off Toulon. Foreseeing the approaching danger, Jervis, about the time Elba was seized, sent Mann orders to rejoin him; and accordingly, on the 29th of July, the blockade of Cadiz was raised. It was just in time, for on the 19th of August Spain, moved by the successes of Bonaparte and the French advance into Germany,—which had not yet undergone the disasters afterwards inflicted upon the separated armies of Jourdan and Moreau by the Archduke Charles,—had signed a treaty of offensive and defensive alliance with the republic. As soon as Mann's ships disappeared, Richery demanded the help of the Spanish fleet to cover his departure, and on the 4th of August sailed in company with twenty Spanish ships-of-the-line. These escorted him three hundred miles to the westward, and then returned to port, leaving the French to fulfil their original mission against British North America, after a detention of nearly ten months. Richery, who had been promoted to rear-admiral during this time, made his cruise successfully, harassed the fishing interests on the coasts of Newfoundland, captured and burned a hundred British merchant vessels, and got back to Brest in time to take part in the unfortunate expedition against Ireland, which sailed in December of this year.

Admiral Mann, though a brave and good officer, showed bad judgment throughout this campaign. Apparently, to use Napoleon's expression, "Il s'était fait un tableau" as to the military and naval situation; and to such a frame of mind the governor of Gibraltar, O'Hara, a pessimist by temperament, 131 probably was a bad adviser. In his precipitation to join the commander-in-chief, he forgot the difficulty about stores and left Gibraltar without filling up. Jervis consequently was forced to send him back at once, with orders to return as quickly as possible. On his way down, on the 1st of October, he was chased by a Spanish fleet of nineteen sail-of-the-line under Admiral Langara. His squadron escaped, losing two merchant vessels under its convoy; but, upon arriving in Gibraltar, he called a council of captains, and, having obtained their concurrence in his opinion, sailed for England, in direct disregard of the commands both of Jervis and the Admiralty. Upon his arrival his action was disapproved, 132 orders were sent him to strike his flag and come ashore, and he appears never again to have been employed afloat; but, when it is remembered that only forty years had elapsed since Byng was shot for an error in judgment, it must be owned men had become more merciful.

Mann's defection reduced Jervis's forces by one third, at a time when affairs were becoming daily more critical. Not only did it make the tenure of the Mediterranean vastly more difficult, but it deprived the admiral of his cherished hope of dealing a staggering blow to the Spanish fleet, such as four months later he inflicted at Cape St. Vincent. After meeting Mann, Langara was joined by seven ships from Cartagena, and with this increase of force appeared on the 20th of October about fifty miles from San Fiorenzo Bay. Jervis had just returned there from off Toulon, having on the 25th of September received orders to evacuate Corsica,—an operation which promised to be difficult from lack of transports. On the 26th of October Langara entered Toulon, where the new allies had then thirty-eight ships-of-the-line collected.

During the summer months Nelson had blockaded Leghorn, after its occupation by the French; and this measure, with the tenure of Elba, seems to have effectually prevented any large body of men passing into Corsica. On the 18th of September the little island of Capraja, a Genoese dependency and convenient refuge for small boats, was seized for the same object. On the 29th, however, Nelson received orders from Jervis for the evacuation of Corsica, the operations at Bastia being assigned to his special care. As soon as the determination of the British was known, discontent broke out into revolt. Gentili, finding the sea clear, landed on the 19th of October, pressing close down upon the coast; and the final embarkation was only effected in safety under the guns of the ships. On the 19th Nelson took off the last of the troops, and carried them with the viceroy to Elba, which it was intended still to hold. Jervis held on at San Fiorenzo Bay to the latest moment possible, everything being afloat for a fortnight before he left, hoping that Mann might yet join, and fearing he might arrive after the departure of the fleet. On the 2d of November provisions were so short that longer delay was impossible; and the admiral sailed with his whole force, reaching Gibraltar, after a tedious voyage, on the 1st of December, 1796. During the passage, in which the crews were on from half to one third the usual rations, Jervis received instructions countermanding the evacuation, if not yet carried out. If executed, Elba was still to be held.

The policy of thus evacuating the Mediterranean admits, now as then, of argument on both sides. The causes for the vacillation of the British government are apparent. The first orders to leave everything, Elba included, were dated August 31. Generals Jourdan and Moreau were then far in the heart of Germany; and the archduke having but just begun the brilliant counter-move by which he drove first one, and then the other, back to the Rhine, the effects of this were in no way foreseen. From Italy the latest possible news was of Bonaparte's new successes at Lonato and Castiglione, and the fresh retreat of the Austrians. The countermanding orders, dated October 21, were issued under the influence of the archduke's success and of Wurmser's evasion of Bonaparte and entrance into Mantua; whereby, despite repeated defeats in the field, the garrison was largely increased and the weary work of the siege must be again begun. While Mantua stood, Bonaparte could not advance; and the Austrians were gathering a new army in the Tyrol. The British government failed, too, to realize the supreme excellence of its Mediterranean fleet and the stanch character of its leader. "The admiral," wrote Elliott 133 on the spot, "is as firm as a rock. He has at present fourteen sail-of-the-line against thirty-six, or perhaps forty. If Mann joins him, they will certainly attack, and they are all confident of victory." The incident of Mann's conduct, under these circumstances, is full of military warning. It is within the limits of reasonable speculation to say that, had he obeyed his orders,—and only extreme causes could justify disobedience,—the battle of Cape St. Vincent would have been fought then in the Mediterranean, 134 instead of in the Atlantic after the fall of Mantua, and would have profoundly affected the policy of the Italian States. With such a victory, men like Jervis and Elliott would have held on for further orders from home. "The expulsion of the English," wrote Bonaparte, "has a great effect upon the success of our military operations in Italy. We must exact more severe conditions of Naples. It has the greatest moral influence upon the minds of the Italians, assures our communications and will make Naples tremble even in Sicily." 135

In the opinion of the author, Sir Gilbert Elliott expresses the correct conclusion in the words following, which show singular foresight as well as sound political judgment: "I have always thought that it is a great and important object in the contest between the French republic and the rest of Europe, that Italy, in whole or in part, should neither be annexed to France as dominion, nor affiliated in the shape of dependent republics; and I have considered a superior British fleet in the Mediterranean as an essential means for securing Italy and Europe from such a misfortune." 136 Elliott's presentiments were realized by Napoleon at a later day; the immediate effect of the evacuation was indicated by a treaty of peace between France and Naples, signed October 10, as soon as the purpose was known. In 1796 the British fleet had been three years in the Mediterranean, and since the acquisition of Corsica had effected little. What was needed at the moment was not an abandonment of the field, but a demonstration of power by a successful battle. The weakest eyes could count the units by which the allied fleets exceeded the British; acts alone could show the real superiority, the predominance in strength, of the latter. That demonstrated, the islands and the remote extremities of the peninsula would have taken heart, and a battle in the Gulf of Lyon had the far-reaching effects produced by that in Aboukir Bay. At the time of the evacuation the three most important factors in the military situation were, the siege of Mantua, the Austrian army in the Tyrol, and, last but not least, the British fleet in the Mediterranean. This sustained Naples; and Naples, or rather southern Italy, was one of Bonaparte's most serious anxieties. Finally, it may be said that the value of Corsica to the fleet is proved by Nelson's preference of Maddalena Bay, in the straits separating Corsica from Sardinia, over Malta, as the station for a British fleet watching Toulon.

Immediately upon reaching Gibraltar, Jervis received orders to take the fleet to Lisbon, in consequence of a disposition shown by the allied French and Spanish governments to attack Portugal. 137 The limits of his command were extended to Cape Finisterre. Before sailing, he despatched Nelson up the Mediterranean with two frigates to bring off the garrison and stores from Elba, the abandonment of which was again ordered. On the 16th he sailed for Lisbon, arriving there on the 21st; but misfortunes were thickening around his fleet. On the 10th, at Gibraltar, during a furious gale, three ships-of-the-line drove from their anchors. One was totally lost on the coast of Morocco, and another struck so heavily on a rock that she had to be sent to England for repairs. Shortly after, a third grounded in Tangiers Bay, and, though repaired on the station, was unfit for service in the ensuing battle. A fourth, when entering the Tagus in charge of a pilot, was run on a shoal and wrecked. Finally, in leaving the river on the 18th of January, a ninety-eight-gun ship was run aground and incapacitated. This reduced the force with which he then put to sea to seek the enemy to ten ships-of-the-line.

Nelson, his most efficient lieutenant, was also nearly lost to him on that interesting occasion, when his fearlessness and coup d'œil mainly contributed to the success achieved. Sailing from Gibraltar on the 15th of December, he fought on the 20th a severe action with two Spanish frigates, which would have made a chapter in the life of an ordinary seaman, but is lost among his other deeds. His prizes were immediately recovered by a heavy Spanish squadron, but his own ships escaped. On the 26th he reached Porto Ferrajo, and remained a month. He was there joined by Elliott, the late viceroy of Corsica, who had been in Naples since the evacuation. General De Burgh, commanding the garrison, refused to abandon his post without specific orders from the government, and as Nelson had only those of Jervis, he confined himself to embarking the naval stores. With these and all the ships of war he sailed from Elba on the 29th of January, 1797. On the 9th of February he reached Gibraltar; and thence, learning that the Spanish fleet had repassed the Straits, he hurried on to join the admiral. Just out of Gibraltar he was chased by several Spaniards, 138 but escaped them, and on the 13th fell in with the fleet. At 6 P. M. of that day he went on board his own ship, the "Captain," seventy-four, at whose masthead flew his broad pennant 139 during the battle of the following day.

The meeting which now took place between the Spanish and British fleets was the result of the following movements. Towards the end of 1796 the Directory, encouraged by Bonaparte's successes and by the Spanish alliance, and allured by the promises of disaffected Irish, determined on an expedition to Ireland. As the first passage of the troops and their subsequent communications would depend upon naval superiority, five ships-of-the-line were ordered from Toulon to Brest. This force, under Admiral Villeneuve, sailed on the 1st of December, accompanied by the Spanish fleet of twenty-six ships, which, since October, had remained in Toulon. On the 6th Langara went into Cartagena, leaving Villeneuve to himself, and on the 10th the French passed Gibraltar in full sight of the British fleet, driving before the easterly gale, which then did so much harm to Jervis's squadron and prevented pursuit. They did not, however, reach Brest soon enough for the expedition. The Spaniards remained in Cartagena nearly two months, during which time Admiral Cordova took command; but under urgent pressure from the Directory 140 they finally sailed for Cadiz on the 1st of February, passing the Straits on the 5th with heavy easterly weather, which drove them far to the westward. They numbered now twenty-seven ships-of-the-line.

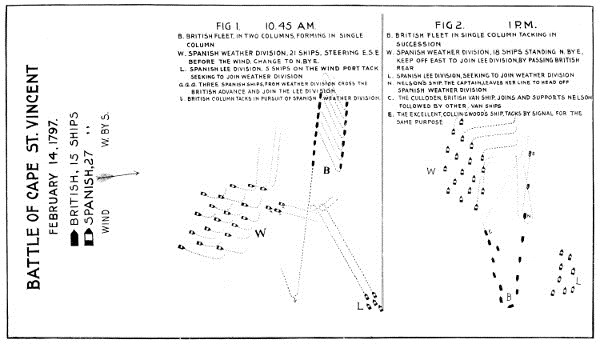

Sir John Jervis, after leaving Lisbon on January 18, 1797, had convoyed to the westward some Portuguese merchant ships bound to Brazil, and then beaten back towards his station off Cape St. Vincent. On the 6th of February he was joined by a re-enforcement of five ships, which were sent from England as soon as the scare about Ireland had passed. With these fifteen he cruised off the Cape, knowing that he there must meet any squadron, from either the Mediterranean or the Atlantic, bound to Cadiz. At 5 A.M. of February 14, the frigate "Niger," which had kept sight of the Spanish fleet for some days, joined the admiral, and informed him that it was probably not more than ten or twelve miles distant, to the southward and westward. The wind, which had been strong south-easterly for several days, had changed during the night to west by south, enabling the Spaniards to head for Cadiz, after the weary battling of the past week; but this otherwise fortunate circumstance became a very dangerous incident 141 to a large, ill-officered, and ill-commanded body of ships, about to meet an enemy so skilful, so alert, and so thoroughly drilled as Jervis's comparatively small and manageable force. At daybreak, about 6.30, the Spaniards were seen, stretching on the horizon from south-west to south in an ill-defined body, across the path of the advancing British. Their distance, though not stated, was probably not less than fifteen to twenty miles. The British fleet being close hauled on the starboard tack, heading from south to south by west, while the Spaniards, bound for Cadiz, were steering east-south-east, the two courses crossed nearly at right angles. At this moment there was a great contrast between the arrays presented by the approaching combatants. The British, formed during the night in two columns of eight and seven ships respectively, elicited the commendation of their exacting chief "for their admirable close order." 142 The Spaniards, on the contrary, eager to get to port, and in confusion through the night shift of wind and their own loose habits of sailing, were broken into two bodies. Of these the leading one, as all were sailing nearly before the wind, was most to leeward. It was composed of six ships, the interval between which and the other twenty-one was probably not less than eight miles. Even after the British fleet was seen, no attempt was for some time made to remedy this fatal separation; a neglect due partly to professional nonchalance and inefficiency, and partly to misinformation concerning the enemy's force, which they had heard through a neutral was only nine ships-of-the-line. 143

Battle of Cape St. Vincent, February 14, 1797.

The weather being hazy and occasionally foggy, some time passed before the gradually approaching enemies could clearly see each other. At 9 A.M. the number and rates of the Spaniards could be made out from the masthead of the British flag-ship, so that they were then probably distant from twelve to fifteen miles. At half-past nine Jervis sent three ships ahead to chase, and a few minutes later supported them with three others. This advanced duty enabled these six to take the lead in the attack. About ten 144 the fog lifted and disclosed the relative situations. The British, still in two columns, were heading fair for the gap in the Spanish order. The six lee ships of the latter had realized their false position, and were now close to the wind on the port tack, heading about north-north-west, in hopes that they could rejoin the main body to windward, which still continued its course for Cadiz. Jervis then made signal to form a single column, the fighting order of battle, and pass through the enemy's line. It soon became evident that the lee Spanish ships could not cross the bows of the British. For a moment they wavered and bore up to south-east; but soon after five of them resumed their north-west course, with the apparent purpose of breaking through the hostile line whose advance they had not been able to anticipate. 145 The sixth continued to the south-east and disappeared.

The weather division of the Spaniards now also saw that it was not possible for all its members to effect a junction with the separated ships. Three stood on, and crossed the bows of the advancing enemy; the remainder hauled up in increasing disorder to the northward, steering a course nearly parallel, but directly opposite, to the British, and passing their van at long cannon shot. At half-past eleven the "Culloden," Captain Troubridge, heading Jervis's column, came abreast the leading ships of this body, and opened fire. Sir John Jervis now saw secured to him the great desire of commanders-in-chief. His own force, in compact fighting order, was interposed between the fractions of the enemy, able to deal for a measurable time with either, undisturbed by the other. Should he attack the eighteen weather, or the eight lee ships, with his own fifteen? With accurate professional judgment he promptly decided to assail the larger body; because the smaller, having to beat to windward, would be kept out of action longer than he could hope if he chose the other alternative. The decision was in principle identical with that which determined Nelson's tactics at the Nile. The signal was therefore made to tack in succession, in pursuit of the weather ships. Troubridge, anticipating the order, had already hoisted at the masthead his answering flag of recognition, rolled up after the manner of the sea, needing but a turn of the wrist to unloose it. Quick as the admiral's signal flew the reply fluttered out, and the "Culloden's" sails were already shaking as she luffed up into the wind. "Look at Troubridge," shouted Jervis, in exultation: "he handles his ship as if the eyes of all England were upon him! and would to God they were!" The rear of the Spaniards was just passing the "Culloden" as she thus went round. Ship after ship of the British line tacked in her wake and stood on in pursuit; while those still on the first course, south by west, interposed between the two Spanish divisions. Of these the lee, led by a hundred-gun ship under a vice-admiral's flag, headed towards Jervis's flag-ship, the "Victory," the seventh in the British order, as though to go through the line ahead of her. The "Victory" was too prompt; and the Spaniard, to avoid collision, went about close under the British broadsides. In doing this he was exposed to and received a raking fire, which drove him out of action, accompanied by his consorts. The "Victory," which had backed a topsail a moment to aim more accurately, then stood on and tacked in the wake of the "Culloden," followed by the rest of the British column.

It was now nearly one o'clock. The action so far had consisted, first, in piercing the enemy's line, cutting off the van and greater part of the centre from the rear; and, second, in a cannonade between two columns passing on opposite parallel courses,—the Spanish main division running free, the British close to the wind. Naval history abounds in instances of these brushes, and pronounces them commonly indecisive. Jervis, who had seen such, 146 meant decisive action when he ordered the "Culloden" to tack and follow the enemy. But a stern chase is a long chase, and the Spanish ships were fast sailers. Some time must pass before Troubridge and his companions could overtake them; and, as each succeeding vessel of the British line had to reach the common point of tacking, from which the Spaniards were steadily receding, the rear of Jervis's fleet must be long in coming up. That it was so is proved by the respective losses incurred. It has, therefore, been suggested that the admiral would have done well to tack his whole fleet, or at least the rear ships together, bringing them in a body on the Spanish van. The idea is plausible, but errs by leaving out of the calculation the Spanish lee division, which was kept off by the British rear ships. Those eight lee ships are apt to be looked on as wholly out of the affair; but in fact it was a necessary part of Jervis's combination to check them, during the time required to deal with the others. Admiral Parker, commanding in the van, speaks expressly of the efforts made by the Spanish lee division to annoy him, and of the covering action of the British rear. 147

Thus, one by one, the British ships were changing their course from south by west to north-north-east in pursuit of the Spanish main division, and the latter was gradually passing to the rear of their enemy's original order. When they saw the sea clear to the south-east, about one o'clock, they bore up, altering their course to east-south-east, hoping to pass behind the British and so join the lee division. Fortunately for Jervis, Nelson was in the third ship from the rear. Having fully divined his chief's purpose, he saw it on the point of defeat, and, without waiting for orders, wore at once out of the line, and threw the "Captain," alone, in front of the enemy's leading ships. In this well-timed but most daring move, which illustrates to the highest degree the immense difference between a desperate and a reckless action, Nelson passed to the head of the British column, crossing the bows of five large Spanish vessels, and then with his seventy-four engaged the "Santisima Trinidad," of one hundred and thirty guns, the biggest ship at that time afloat. The enemy, apparently dashed by this act of extraordinary temerity, and as little under control as a flock of frightened sheep, hauled up in a body again to north-north-east, resuming what can only be described as their flight.

Their momentary change of course had, however, caused a delay which enabled the British leaders to come up. Troubridge in the "Culloden" was soon right behind Nelson, to whom he was dear beyond all British officers, and three other ships followed in as close array as was consistent with the free use of their guns. The Spaniards, never in good order, lay before them in confusion, two or three deep, hindering one another's fire, and presenting a target that could not easily be missed. This closing scene of the battle raged round the rear ships of the Spanish main body, and necessarily became a mêlée, each British captain acting according to his own judgment and the condition of his ship. A very distinguished part fell to Collingwood, likewise a close associate of Nelson's, whose ship, the "Excellent," had brought up the rear of the order. Having, probably from this circumstance, escaped serious injury to her spars, she was fully under her captain's control, and enabled him to display the courage and skill for which he was so eminently distinguished. Passing along the enemy's rear, he had compelled one seventy-four to strike, when his eye caught sight of Nelson's ship lying disabled on the starboard side, and within pistol shot, of the "San Nicolas," a Spanish eighty; "her foretopmast and wheel shot away, not a sail, shroud, or rope, left," 148 and being fired upon by five hostile ships. With every sail set he pressed ahead, passing between the "Captain" and her nearest enemy, brushing the latter at a distance of ten feet, and pouring in one of those broadsides of which he used to assure his practised crew that, if they could fire three in five minutes, no vessel could resist them. The "San Nicolas," either intentionally or from the helmsman being killed, luffed and fell on board the "San Josef," a ship of one hundred and twelve guns, while the "Excellent," continuing her course, left the ground again clear for Nelson. The latter, seeing the "Captain" powerless for continued manœuvre, put the helm to starboard; the British ship came up to the wind, fetched over to the "San Nicolas," and grappled her. Nelson, having his men ready on deck, rushed at their head on board the Spaniard, drove her crew below, and captured her. The "San Josef," which was fast to the "San Nicolas" on the other side, now opened a fire of musketry; but the commodore, first stationing sentinels to prevent the "San Nicolas's" men regaining their deck, called upon his own ship for a re-enforcement, with which he boarded the three-decker and carried her also. On her quarter-deck, surrounded by his followers still hot from the fight, he received the swords of the Spanish officers.