полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire 1793-1812, vol I

The "Queen," though much crippled, had, with her head to the eastward, passed astern of the two threatened French ships. These had suffered from the engagement, in passing, with the British van a few hours before, as well as with the flying squadron on the previous day; and the injuries then received had doubtless contributed to place them in the exposed and dangerous position they now occupied. The "Leviathan," seventy-four, attacked them to windward, the "Orion," of the same class, to leeward, and the latter was soon after re-enforced and replaced by the "Barfleur," of ninety-eight guns. No particular statement is given in the British narratives of other ships attacking these two, but several of those astern of the "Queen Charlotte," which could have reached no other of the French, lost killed and wounded, and it is probable that these shared in this encounter. The French accounts speak of their two vessels as "surrounded;" and Villaret wrote that their resistance "should immortalize their captains, Dordelin and Lamesle." They came out of the engagement of the 29th of May with only their lower masts standing; and the heavier of the two, the "Indomptable," was in such condition that Villaret thought necessary to send her to Brest that night, escorted by another of his fleet, which was thus dwindling piece-meal.

For the moment, however, the French admiral's manœuvre, well conceived and gallantly executed, rescued the endangered ships. The "Queen Charlotte" and her immediate supporters, after first tacking, had barely reached the rear of the French. As the latter continued to stand on, it was of course impossible for all the fifteen ships behind the British admiral to come up with them at once. In fact, the failure of the van to do its whole duty, combined with the remote position of the rear,—increased probably by the straggling usually to be observed at the tail of long columns,—had resulted in throwing the British order into confusion. "As the ships arrived," wrote Lord Howe in his journal, "they came up so crowded together as afforded an opportunity for the enemy to have fired upon them with great advantage." (Fig. 3, C, R.) "The British line was completely deformed," states one French authority. But, though disordered, they formed a large and dangerous body, all within supporting distance,—they had on their side the prestige of an indisputable, though partial, success,—they were flushed with victory, and it would appear that the French van had not yet come up. Villaret therefore contented himself with carrying off his rescued ships, with which and with the rest of his fleet he stood away to the north-west.

It is desirable to sum up the result of these two days of partial encounters, as an important factor in the discussion of the campaign as a whole, which must shortly follow. On the morning of May 28, the French numbered twenty-six ships-of-the-line 82 and were, when they first formed line, from ten to twelve miles to windward of the British, also numbering twenty-six. On the evening of May 29, in consequence of Howe's various movements and the course to which Villaret was by them constrained,—for he acted purely on the defensive and had to conform to the initiative of the enemy,—the French fleet was to leeward of the British. As Howe had succeeded within so short a time in forcing action from to leeward, there was every reason to apprehend that from the windward position—decidedly the more favorable upon the whole, though not without its drawbacks—he would be able to compel a decisive battle, which the French naval policy proscribed generally, and in the present case particularly. Besides this adverse change of circumstance, the balance of loss was still more against the French. On the first day the "Révolutionnaire" on one side and the "Audacious" on the other had been compelled to quit their fleets; but the force of the latter was not over two thirds that of the former. By the action of the 29th the "Indomptable," of eighty guns, was driven from the French fleet, and the admiral thought necessary to send with her a seventy-four and a frigate. The "Tyrannicide," seventy-four, had lost all her upper masts; she had consequently to be towed by one of her consorts through the next two days and in the battle of the First of June. If Villaret had had any expectation of escaping Howe's pursuit, the presence of this disabled ship would have destroyed it, unless he was willing to abandon her. Besides the mishaps already stated, the leading ship, "Montagnard," had been so much injured in the early part of the engagement that she could not go about. Continuing to stand west, while the body of the fleet was running east to the aid of the "Indomptable" and "Tyrannicide," this ship separated from her consorts and was not able to regain them. To this loss of four ships actually gone, and one permanently crippled, may be added that of the "Audacieux," one of Nielly's squadron, which joined on the morning of the 29th, but was immediately detached to seek and protect the "Révolutionnaire." On the other hand, the British had by no means escaped unscathed; but on the morning of the 30th, in reply to an interrogatory signal from the admiral, they all reported readiness to renew the action, except one, the "Cæsar," which was not among the most injured. This ship, however, did not leave the fleet, and was in her station in the battle of the First.

The merit of Howe's conduct upon these two days does not, however, depend merely upon the issue, though fortunate. By persistent attacks, frequently renewed upon the same and most vulnerable part of the French order, he had in effect brought to bear a large part of his own fleet upon a relatively small number of the enemy, the result being a concentration of injury which compelled the damaged ships to leave the field. At the same time the direction of the attack forced the French admiral either to abandon the endangered vessels, or step by step to yield the advantage of the wind until it was finally wrested from him altogether. By sheer tactical skill, combined with a fine display of personal conduct, Howe had won a marked numerical preponderance for the decisive action, which he now had good reason to expect from the advantageous position likewise secured. Unfortunately, the tactical gain was soon neutralized by the strategic mistake which left Montagu's squadron unavailable on the day of battle.

Towards the close of the day the weather grew thick, and so continued, with short intervals of clearing, for the next thirty-six hours. At half-past seven the body of the French bore from the British flag-ship north-west, distant nine or ten miles; both fleets standing very slowly to the westward and a little northerly, with wind from the southward and westward. During most of the 30th, none of the British fleet could be seen from the flag-ship, but they all, as well as the French, kept together. On that day also, by a piece of great good fortune considering the state of the weather, Admiral Nielly joined Villaret with the three ships still under his command, as did also another seventy-four belonging to the Cancale squadron. These four fresh ships exactly replaced the four disabled ones that had parted company, and again made the French twenty-six to Howe's twenty-five.

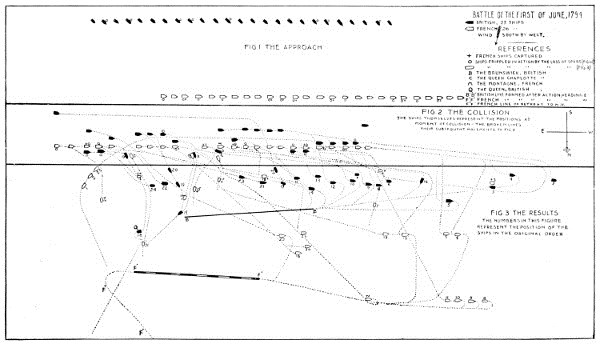

About ten o'clock in the morning of May 31st, the fog lifted for a moment, allowing Howe to count twenty-seven sail of his ships and frigates; and, after again shutting down for a couple of hours, it finally dispersed shortly after noon. The French were then seen bearing from west to north-west. The British made sail in chase and by six P.M. had approached to within about three miles. They were not, however, able to reach the position Howe wished—abreast the enemy—early enough to permit the intended general engagement, unless by a night action; which for more than one reason the admiral was not willing to undertake. He therefore hauled again to the wind, heading to the westward in order of battle. The French had formed on a parallel line and were running in the same direction. During the night both fleets carried all the sail their masts would stand. In the morning the French, thanks to the better sailing of their vessels, were found to have gained somewhat on their enemies, but not sufficiently to avoid or postpone the battle, which they had been directed if possible to shun. Villaret therefore formed his fleet in close order, and stood on slowly under short canvas, which at once allowed irregularities in the order to be more easily corrected and also left the crews free to devote themselves exclusively to fighting the ships. Howe, by carrying sail, was thus able to choose his position prior to bearing down. Having reached it and formed his line, the French being now hove-to to await the attack, the British fleet was also hove-to, and the crews went to breakfast. At twelve minutes past eight it again filled-away by signal, and stood slowly down for the enemy (June 1, Fig. 1). The intention being to attack along the whole line, ship to ship, advantage was taken of this measured approach to change the place of the three-decked ships in the order, so that they should be opposed to the heaviest of the French. Lord Howe, who in the matter of drill was something of a precisian, is said to have rectified the alignment of his fleet more than once as it stood down; and, unless some such delay took place, it is difficult to reconcile the rate of sailing of the ships with the time it took them to cover the ground. The combatants had a long summer's day before them, and such scrupulous care was not wholly out of place in an attack of the kind; for not only was it desirable that the shock should be felt everywhere at once, but ships in advance of the line would invite concentration of fire from the enemy, while those much in the rear would be embarrassed by smoke concealing the position it behooved them to take.

Battle of the First of June, 1794.

This difficulty from smoke was the more to be feared because Howe's plan, as communicated to the fleet by signal, was not merely to attack on the side from which he approached, but to pass through the intervals between the enemy's ships, and to engage them on the further, or lee, side. This method conferred the advantage of a raking fire 83 while passing through the line, and cut off the retreat of disabled enemies; for a crippled ship could only retire to leeward. 84 To carry out the design, however, required not only that the enemy should leave wide enough intervals, but also that the assailants should be able to see where the intervals were.

The British ships were steering each for its opposite in the enemy's order, heading about north-west; so that, as the French line was east and west, the approach was not perpendicular but in a slanting direction. At twenty minutes before nine, the formation was so accurate that Lord Howe shut the signal book with an air of satisfaction, as though his work as admiral was done and all that remained was to show the gallant bearing and example which had ever been associated with his name. The gesture was, however, premature, and eccentricities of conduct on the part of some captains compelled him again to open the book and order them into their stations. Shortly after nine o'clock the French van began firing. The British ship "Cæsar," on the left flank of her line, and therefore corresponding to the leader of the French, instead of pressing on to her station for battle, hauled to the wind and began firing while still five hundred yards distant,—a position inconsistent with decisive results under the gunnery conditions of that day. Lord Howe, who had not thought well of the captain of this ship, but had permitted him to retain his distinguished position in the order at the request of the captain of the "Queen Charlotte," now tapped the latter on the shoulder, and said, "Look, Curtis, there goes your friend; who is mistaken now?"

The rest of the fleet stood on. The "Queen Charlotte," in order to reach her position, had to steer somewhat more to the westward. Either the French line had drawn a little ahead, or some other incident had thrown this ship astern of her intended point of arrival. Her course, therefore, becoming more nearly parallel to the enemy's, she passed within range of the third vessel behind Villaret's flag-ship, the "Montagne," her destined opponent. This ship, the "Vengeur," opened fire upon her at half-past nine. The "Queen Charlotte," not to be crippled before reaching her place, made more sail and passed on. The next ahead of the "Vengeur," the "Achille," also engaged her, and to this the "Charlotte" replied at eight minutes before ten. The assailant suffered severely, and her attention was quickly engrossed by the "Brunswick," the supporter of Howe's flag-ship on her starboard side, which tried to break through the line ahead of the "Achille."

The "Queen Charlotte" (June 1, Fig. 2, C) continued on for the "Montagne" (M). Seeing her evident purpose to pass under the stern, the captain of this ship threw his sails aback, so as to fall to the rear and close the interval. At the same moment the French ship next astern, the "Jacobin," increased her sail, most properly, for the same object. The two thus moving towards each other, a collision was threatened. As the only alternative, the "Jacobin" put her helm up and steered for the starboard, or lee, side of the "Montagne." At this moment the "Queen Charlotte" drew up. Putting her helm hard over, she kept away perpendicularly to the "Montagne," and passed under her stern, so close that the French flag brushed the side of the British ship. One after another the fifty guns of the latter's broadside swept from stern to stem of the enemy,—three hundred of her crew falling at once, her captain among the number. The "Jacobin" having moved to the starboard side of the "Montagne," in the place the "Queen Charlotte" had intended to take, it was thought that the latter would have to go to leeward of both; but, amid all the confusion of the scene, the quick eye of the gallant man who was directing her movements caught a glimpse of the "Jacobin's" rudder and saw it moving to change the ship's direction to leeward. Quickly seizing his opportunity, the helm of the British flag-ship was again shifted, and she came slowly and heavily to the wind in her appointed place, her jib-boom in the movement just clearing the "Jacobin," as her side a few minutes before had grazed the flag of the "Montagne." The latter, it is said, made no reply to this deadly assault. The "Jacobin" fired a few shots, one of which cut away the foretopmast of the "Queen Charlotte;" and then, instead of imitating the latter's movement and coming to the wind again, by which the British ship would have been placed between his fire and that of the "Montagne," the captain weakly kept off and ran to leeward out of action.

By this time the engagement was general all along the line (Fig. 2). Smoke, excitement and the difficulties of the situation broke somewhat the simultaneousness of the shock of the British assault; but, with some exceptions, their fire from van to rear opened at nearly the same time. Six ships only passed at once through the enemy's line, but very many of the others brought their opponents to close action to windward. In this, the first pitched battle after many years of peace, there were found the inevitable failures in skill, the more sorrowful shortcomings of many a fair-seeming man. To describe minutely the movements of every ship would not tend to clearness, but to obscurity. For general impression of the scene at certain distinctive moments the reader is referred to the diagrams; in which, also, an attempt has been made to represent the relative motions of the ships in both squadrons, so far as can be probably deduced from the narratives. (See Figs. 2 and 3.)

There was, however, one episode of so singular, so deadly, and yet so dramatic an interest, occurring in the midst of this extensive mêlée, that it cannot be passed by. As long as naval history shall be written, it must commemorate the strife between the French ship "Vengeur du Peuple" and the British ship "Brunswick." The latter went into action on the right hand of the "Queen Charlotte;" its duty therefore was to pierce the French line astern of the "Jacobin." This was favored by the movement of the latter to support the "Montagne;" but, as the "Brunswick" pressed for the widened gap, the "Achille" made sail ahead and threw herself in the way. Foiled here, the "Brunswick" again tried to traverse the line astern of the "Achille," but the "Vengeur" now came up, and, as the "Brunswick" persisted, the two collided and swung side to side, the anchors of the British ship hooking in the rigging and channels of the French. Thus fastened in deadly embrace, they fell off before the wind and went away together to leeward (Fig. 2, B).

As the contact of the two ships prevented opening the lower ports as usual, the British crew blew off the lids. The "Vengeur" having already been firing from the side engaged, hers were probably open; but, owing to the hulls touching, it was not possible to use the ordinary sponges and rammers, with rigid wooden staves, and the French had no other. The British, however, were specially provided for such a case with sponges and rammers having flexible rope handles, and with these they were able to carry on the action. In this way the contest continued much to the advantage of the British on the lower decks, where the French, for the reason given, could use only a few of the forward and after guns, the form of a ship at the extremities causing the distance there between the combatants to be greater. But while such an inequality existed below, above the balance was reversed; the heavy carronades of the "Vengeur," loaded with langrage, and the superiority of her musketry,—re-enforced very probably by the men from the useless cannon below,—beating down the resistance of the British crew on the upper deck and nearly silencing their guns. The captain of the "Brunswick" received three wounds, from one of which he afterwards died; and a number of others, both officers and men, were killed and wounded. This circumstance encouraged the "Vengeur's" commander to try to carry his opponent by boarding; but, when about to execute the attempt, the approach of two other British ships necessitated calling off the men, to serve the guns on the hitherto disengaged side.

Meanwhile the "Brunswick's" crew maintained an unremitting fire, giving to their guns alternately extreme elevation and depression, so that at one discharge the shot went up through the "Vengeur's" decks, ripping them open, while at the other they tended to injure the bottom. The fight had thus continued for an hour when the "Achille," with only her foremast standing, was seen approaching the "Brunswick" on her port, or disengaged, side. The threatened danger was promptly met and successfully averted. Before the new enemy could take a suitable position, half-a-dozen guns' crews on each of the lower decks shifted to the side on which she was, and in a few moments their fire brought down her only remaining and already damaged mast. The "Achille" had no farther part in the battle and was taken possession of by the British a few hours later.

At quarter before one the uneasy motions of the two ships wrenched the anchors one after another from the "Brunswick's" side, and after a grapple of three hours they separated. The character of the contest, as described, had caused the injury to fall mainly upon the hulls and crews, while the spars and rigging, contrary to the usual result in so fierce an action, had largely escaped. As they were parting, the "Brunswick" poured a few final shots into the "Vengeur's" stern, injuring the rudder, and increasing the leaks from which the doomed ship was already suffering. Immediately afterwards the mizzen-mast of the British vessel went overboard; and, being already well to leeward of her own fleet and threatened by the approach of the French admiral, she stood to the northward under such sail as her spars would bear, intending to make a home port, if possible. In this long and desperate conflict, besides the injuries to be expected to hull and spars, the "Brunswick" had twenty-three of her seventy-four guns dismounted, and had lost forty-four killed and one hundred and fourteen wounded out of a crew of six hundred men. 85

Soon after the dismasting of the "Achille," the British ship "Ramillies," commanded by the brother of the "Brunswick's" captain, had been seen coming slowly down toward the two combatants. She arrived but a few moments before their separation, and, when they were far enough apart for her fire not to endanger the "Brunswick," she also attacked the "Vengeur," but not long after left her again in order to secure the "Achille." This fresh onslaught, however, brought down all the "Vengeur's" masts except the mizzen, which stood for half an hour longer. The French ship was helpless. With numerous shot-holes at or near the water line, with many of her port lids gone, she was rolling heavily in the waves, unsteadied by masts, and taking in water on all sides. Guns were thrown overboard, pumps worked and assisted by bailing, but all in vain,—the "Vengeur" was slowly but surely sinking. At half-past one the danger was so evident that signals of distress were made; but among the disabled or preoccupied combatants they for a long time received no attention. About six P.M., fortunately, two British ships and a cutter drew near, and upon learning the state of the case sent all their boats that remained unhurt. It was too late to save every survivor of this gallant fight, but nearly four hundred were taken off; the remainder, among whom were most of the badly wounded, went down with their ship before the British boats had regained their own. "Scarcely had the boats pulled clear of the sides, when the most frightful spectacle was offered to our gaze. Those of our comrades who remained on board the 'Vengeur du Peuple,' with hands raised to Heaven, implored with lamentable cries the help for which they could no longer hope. Soon disappeared the ship and the unhappy victims which it contained. In the midst of the horror with which this scene inspired us all, we could not avoid a feeling of admiration mingled with our grief. As we drew away, we heard some of our comrades still making prayers for the welfare of their country; the last cries of these unfortunates were: 'Vive la République!' They died uttering them." 86 A touching picture of brave men meeting an inevitable fate, after doing all that energy and courage could to avoid it; very different from the melodramatic mixture of tinsel verbiage and suicide which found favor with the National Convention, and upon which the "Legend of the Vengeur" was based. 87 Of the seven hundred and twenty-three who composed her crew, three hundred and fifty-six were lost; two hundred and fifty of whom were, by the survivors, believed to have been killed or wounded in the three actions.

Long before the "Vengeur" and the "Brunswick" separated, the fate of the battle had been decided, and the final action of the two commanders-in-chief taken. It was just ten o'clock when the British flag-ship passed under the stern of the "Montagne." At ten minutes past ten the latter, whose extensive injuries were mainly to the hull, made sail in advance,—a movement which the "Queen Charlotte," having lost both fore and main topmasts, was unable to follow. Many of the French ships ahead of the "Montagne" had already given ground and left their posts; others both before and behind her had been dismasted. Between half-past ten and eleven the smoke cleared sufficiently for Villaret to see the situation on the field of battle.

Ships dismasted not only lose their power of motion, but also do not drift to leeward as rapidly as those whose spars are up, but which are moving very slowly. In consequence, the lines having some movement ahead, the dismasted ships of both parties had tended astern and to windward of the battle. There they lay, British and French, pell-mell together. Of the twelve ahead of the French admiral when the battle began, seven had soon run out of action to leeward. Two of these, having hauled to the wind on the other tack, were now found to be astern and to windward of both fleets; to windward even of the dismasted ships. Of the rest of the twelve, one, having lost main and mizzen masts, was unavoidably carried to leeward, and the remaining four were totally dismasted. Of these four, three finally fell into the hands of the British. Of the thirteen ships astern of the "Montagne," six had lost all their masts, and one had only the foremast standing; the remaining six had their spars left in fairly serviceable condition, and had, some sooner and some later, retreated to leeward. Four of the dismasted ships in the rear, including among them the "Vengeur," were captured by the British.