полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 5 (of 9)

TO MR. CLINTON

Washington, May 24, 1807.Th: Jefferson presents his compliments to Mr. Clinton, and his thanks for the pamphlet sent him. He recollects the having read it at the time with a due sense of his obligation to the author, whose name was surmised, though not absolutely known, and a conviction that he had made the most of his matter. The ground of defence might have been solidly aided by the assurance (which is the absolute fact) that the whole story fathered on Mazzei, was an unfounded falsehood. Dr. Linn, as aware of that, takes care to quote it from a dead man, who is made to quote from one residing in the remotest part of Europe. Equally false was Dr. Linn's other story about Bishop Madison's lawn sleeves, as the Bishop can testify, for certainly Th: J. never saw him in lawn sleeves. Had the Doctor ventured to name time, place, and person, for his third lie, (the government without religion) it is probable he might have been convicted on that also. But these are slander and slanderers, whom Th: Jefferson has thought it best to leave to the scourge of public opinion. He salutes Mr. Clinton with esteem and respect.

TO GEORGE HAY, ESQ

Washington, May 26, 1807.Dear Sir,—We are this moment informed by a person who left Richmond since the 22d, that the prosecution of Burr had begun under very inauspicious symptoms by the challenging and rejecting two members of the Grand Jury, as far above all exception as any two persons in the United States. I suppose our informant is inaccurate in his terms, and has mistaken an objection by the criminal and voluntary retirement of the gentlemen with the permission of the court, for a challenge and rejection, which, in the case of a Grand Jury, is impossible. Be this as it may, and the result before the formal tribunal, fair or false, it becomes our duty to provide that full testimony shall be laid before the Legislature, and through them the public. For this purpose, it is necessary that we be furnished with the testimony of every person who shall be with you as a witness. If the Grand Jury find a bill, the evidence given in court, taken as verbatim as possible, will be what we desire. If there be no bill, and consequently no examination before court, then I must beseech you to have every man privately examined by way of affidavit, and to furnish me with the whole testimony. In the former case, the person taking down the testimony as orally delivered in court, should make oath that he believes it to be substantially correct. In the latter case, the certificate of the magistrate administering the oath, and signature of the party, will be proper; and this should be done before they receive their compensation, that they may not evade examination. Go into any expense necessary for this purpose, and meet it from the funds provided by the Attorney General for the other expenses. He is not here, or this request would have gone from him directly. I salute you with friendship and respect.

TO MR. HAY

Washington, May 28, 1807.Dear Sir,—I have this moment received your letter of the 25th, and hasten to answer it. If the grand jury do not find a bill against Burr, as there will be no examination before a petty jury, Bollman's pardon need not in that case to be delivered; but if a bill be found, and a trial had, his evidence is deemed entirely essential, and in that case his pardon is to be produced before he goes to the book. In my letter of the day before yesterday, I enclosed you Bollman's written communication to me, and observed you might go so far, if he prevaricated, as to ask him whether he did not say so and so to Mr. Madison and myself. On further reflection I think you may go farther, if he prevaricates grossly, and show the paper to him, and ask if it is not his handwriting, and confront him by its contents. I enclose you some other letters of Bollman to me on former occasions, to prove by similitude of hand that the paper I enclosed on the 26th was of his handwriting. I salute you with esteem and respect.

TO COLONEL MONROE

Washington, May 29, 1807.Dear Sir,—I have not written to you by Mr. Purviance, because he can give you vivâ voce all the details of our affairs here, with a minuteness beyond the bounds of a letter, and because, indeed, I am not certain this letter will find you in England. The sole object in writing it, is to add another little commission to the one I had formerly troubled you with. It is to procure for me "a machine for ascertaining the resistance of ploughs or carriages, invented and sold by Winlaw, in Margaret street, Cavendish Square." It will cost, I believe, four or five guineas, which shall be replaced here instanter on your arrival. I had intended to have written you to counteract the wicked efforts which the federal papers are making to sow tares between you and me, as if I were lending a hand to measures unfriendly to any views which our country might entertain respecting you. But I have not done it, because I have before assured you that a sense of duty, as well as of delicacy, would prevent me from ever expressing a sentiment on the subject, and that I think you know me well enough to be assured I shall conscientiously observe the line of conduct I profess. I shall receive you on your return with the warm affection I have ever entertained for you, and be gratified if I can in any way avail the public of your services. God bless you and yours.

TO M. SILVESTRE, SECRETAIRE DE LA SOCIETE D'AGRICULTURE DE PARIS

Washington, May 29, 1807.Sir,—I have received, through the care of Gen. Armstrong, the medal of gold by which the society of agriculture at Paris have been pleased to mark their approbation of the form of a mould-board which I had proposed; also the four first volumes of their memoirs, and the information that they had honored me with the title of foreign associate to their society. I receive with great thankfulness these testimonies of their favor, and should be happy to merit them by greater services. Attached to agriculture by inclination, as well as by a conviction that it is the most useful of the occupations of man, my course of life has not permitted me to add to its theories the lessons of practice. I fear, therefore, I shall be to them but an unprofitable member, and shall have little to offer of myself worthy their acceptance. Should the labors of others, however, on this side the water, produce anything which may advance the objects of their institution, I shall with great pleasure become the instrument of its communication, and shall moreover execute with zeal any orders of the society in this portion of the globe. I pray you to express to them my sensibility for the distinctions they have been pleased to confer on me, and to accept yourself the assurances of my high consideration and respect.

TO GEORGE HAY

Washington, June 2, 1807.Dear Sir,—While Burr's case is depending before the court, I will trouble you, from time to time, with what occurs to me. I observe that the case of Marbury v. Madison has been cited, and I think it material to stop at the threshold the citing that case as authority, and to have it denied to be law. 1. Because the judges, in the outset, disclaimed all cognizance of the case, although they then went on to say what would have been their opinion, had they had cognizance of it. This, then, was confessedly an extrajudicial opinion, and, as such, of no authority. 2. Because, had it been judicially pronounced, it would have been against law; for to a commission, a deed, a bond, delivery is essential to give validity. Until, therefore, the commission is delivered out of the hands of the executive and his agents, it is not his deed. He may withhold or cancel it at pleasure, as he might his private deed in the same situation. The Constitution intended that the three great branches of the government should be co-ordinate, and independent of each other. As to acts, therefore, which are to be done by either, it has given no control to another branch. A judge, I presume, cannot sit on a bench without a commission, or a record of a commission; and the Constitution having given to the judiciary branch no means of compelling the executive either to deliver a commission, or to make a record of it, shows it did not intend to give the judiciary that control over the executive, but that it should remain in the power of the latter to do it or not. Where different branches have to act in their respective lines, finally and without appeal, under any law, they may give to it different and opposite constructions. Thus, in the case of William Smith, the House of Representatives determined he was a citizen; and in the case of William Duane, (precisely the same in every material circumstance,) the judges determined he was no citizen. In the cases of Callendar and others, the judges determined the sedition act was valid under the Constitution, and exercised their regular powers of sentencing them to fine and imprisonment. But the executive determined that the sedition act was a nullity under the Constitution, and exercised his regular power of prohibiting the execution of the sentence, or rather of executing the real law, which protected the acts of the defendants. From these different constructions of the same act by different branches, less mischief arises than from giving to any one of them a control over the others. The executive and Senate act on the construction, that until delivery from the executive department, a commission is in their possession, and within their rightful power; and in cases of commissions not revocable at will, where, after the Senate's approbation and the President's signing and sealing, new information of the unfitness of the person has come to hand before the delivery of the commission, new nominations have been made and approved, and new commissions have issued.

On this construction I have hitherto acted; on this I shall ever act, and maintain it with the powers of the government, against any control which may be attempted by the judges, in subversion of the independence of the executive and Senate within their peculiar department. I presume, therefore, that in a case where our decision is by the Constitution the supreme one, and that which can be carried into effect, it is the constitutionally authoritative one, and that that by the judges was coram non judice, and unauthoritative, because it cannot be carried into effect. I have long wished for a proper occasion to have the gratuitous opinion in Marbury v. Madison brought before the public, and denounced as not law; and I think the present a fortunate one, because it occupies such a place in the public attention. I should be glad, therefore, if, in noticing that case, you could take occasion to express the determination of the executive, that the doctrines of that case were given extrajudicially and against law, and that their reverse will be the rule of action with the executive. If this opinion should not be your own, I would wish it to be expressed merely as that of the executive. If it is your own also, you would of course give to the arguments such a development as a case, incidental only, might render proper. I salute you with friendship and respect.

TO ALBERT GALLATIN

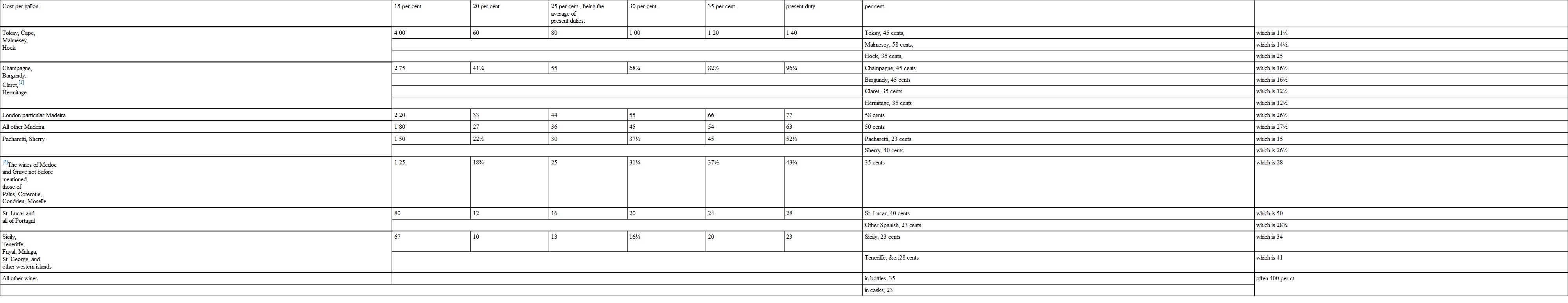

June 3, 1807.I gave you, some time ago, a project of a more equal tariff on wines than that which now exists. But in that I yielded considerably to the faulty classification of them in our law. I have now formed one with attention, and according to the best information I possess, classing them more rigorously. I am persuaded that were the duty on cheap wines put on the same ratio with the dear, it would wonderfully enlarge the field of those who use wine, to the expulsion of whiskey. The introduction of a very cheap wine (St. George) into my neighborhood, within two years past, has quadrupled in that time the number of those who keep wine, and will ere long increase them tenfold. This would be a great gain to the treasury, and to the sobriety of our country. I will here add my tariff, (see opposite page,) wherein you will be able to choose any rate of duty you please, and to decide whether it will not, on a fit occasion, be proper for legislative attention. Affectionate salutations.

1 The term Claret should be abolished, because unknown in the country where it is made, and because indefinite here. The four crops should be enumerated here instead of Claret, and all other wines to which that appellation has been applied, should fall into the ad valorem class. The four crops are Lafitte, Latour and Margaux, in Medoc, and Hautbrion, in Grave.

2 Blanquefort, Oalon, Leoville, Cantenac, &c., are wines of Medoc. Barsac, Sauterne, Beaume, Preignac, St. Bris, Carbonien, Langon, Podensac, &c., are of Grave. All these are of the second order, being next after the four crops.

TO GEORGE HAY

Washington, June 5, 1807.Dear Sir,—Your favor of the 31st instant has been received, and I think it will be fortunate if any circumstance should produce a discharge of the present scanty grand jury, and a future summons of a fuller; though the same views of protecting the offender may again reduce the number to sixteen, in order to lessen the chance of getting twelve to concur. It is understood, that wherever Burr met with subjects who did not choose to embark in his projects, unless approved by their government, he asserted that he had that approbation. Most of them took his word for it, but it is said that with those who would not, the following stratagem was practised. A forged letter, purporting to be from General Dearborne, was made to express his approbation, and to say that I was absent at Monticello, but that there was no doubt that, on my return, my approbation of his enterprises would be given. This letter was spread open on his table, so as to invite the eye of whoever entered his room, and he contrived occasions of sending up into his room those whom he wished to become witnesses of his acting under sanction. By this means he avoided committing himself to any liability to prosecution for forgery, and gave another proof of being a great man in little things, while he is really small in great ones. I must add General Dearborne's declaration, that he never wrote a letter to Burr in his life, except that when here, once in a winter, he usually wrote him a billet of invitation to dine. The only object of sending you the enclosed letters is to possess you of the fact, that you may know how to pursue it, if any of your witnesses should know anything of it. My intention in writing to you several times, has been to convey facts or observations occurring in the absence of the Attorney General, and not to make to the dreadful drudgery you are going through the unnecessary addition of writing me letters in answer, which I beg you to relieve yourself from, except when some necessity calls for it. I salute you with friendship and respect.

TO MR. WEAVER

Washington, June 7, 1807.Sir,—Your favor of March 30th never reached my hands till May 16th. The friendly views it expresses of my conduct in general give me great satisfaction. For these testimonies of the approbation of my fellow citizens, I know that I am indebted more to their indulgent dispositions than to any peculiar claims of my own. For it can give no great claims to any one to manage honestly and disinterestedly the concerns of others trusted to him. Abundant examples of this are always under our eye. That I should lay down my charge at a proper season, is as much a duty as to have borne it faithfully. Being very sensible of bodily decays from advancing years, I ought not to doubt their effect on the mental faculties. To do so would evince either great self-love or little observation of what passes under our eyes; and I shall be fortunate if I am the first to perceive and to obey this admonition of nature. That there are in our country a great number of characters entirely equal to the management of its affairs, cannot be doubted. Many of them, indeed, have not had opportunities of making themselves known to their fellow citizens; but many have had, and the only difficulty will be to choose among them. These changes are necessary, too, for the security of republican government. If some period be not fixed, either by the Constitution or by practice, to the services of the First Magistrate, his office, though nominally elective, will, in fact, be for life; and that will soon degenerate into an inheritance. Among the felicities which have attended my administration, I am most thankful for having been able to procure coadjutors so able, so disinterested, and so harmonious. Scarcely ever has a difference of opinion appeared among us which has not, by candid consultation, been amalgamated into something which all approved; and never one which in the slightest degree affected our personal attachments. The proof we have lately seen of the innate strength of our government, is one of the most remarkable which history has recorded, and shows that we are a people capable of self-government, and worthy of it. The moment that a proclamation apprised our citizens that there were traitors among them, and what was their object, they rose upon them wherever they lurked, and crushed by their own strength what would have produced the march of armies and civil war in any other country. The government which can wield the arm of the people must be the strongest possible. I thank you for the interest you are so kind as to express in my health and welfare, and return you the same good wishes with my salutations, and assurance of respect.

TO DOCTOR HORATIO TURPIN

Washington, June 10, 1807.Dear Sir,—Your favor of June the 1st has been received. To a mind like yours, capable in any question of abstracting it from its relation to yourself, I may safely hazard explanations, which I have generally avoided to others on questions of appointment. Bringing into office no desires of making it subservient to the advancement of my own private interests, it has been no sacrifice, by postponing them, to strengthen the confidence of my fellow citizens. But I have not felt equal indifference towards excluding merit from office, merely because it was related to me. However, I have thought it my duty so to do, that my constituents may be satisfied, that, in selecting persons for the management of their affairs, I am influenced by neither personal nor family interests, and especially, that the field of public office will not be perverted by me into a family property. On this subject, I had the benefit of useful lessons from my predecessors, had I needed them, marking what was to be imitated and what avoided. But in truth, the nature of our government is lesson enough. Its energy depending mainly on the confidence of the people in the chief magistrate, makes it his duty to spare nothing which can strengthen him with that confidence.

* * * * * * * *Accept assurances of my constant friendship and respect.

TO JOHN NORVELL

Washington, June 11, 1807.Sir,—Your letter of May the 9th has been duly received. The subject it proposes would require time and space for even moderate development. My occupations limit me to a very short notice of them. I think there does not exist a good elementary work on the organization of society into civil government: I mean a work which presents in one full and comprehensive view the system of principles on which such an organization should be founded, according to the rights of nature. For want of a single work of that character, I should recommend Locke on Government, Sidney, Priestley's Essay on the first Principles of Government, Chipman's Principles of Government, and the Federalist. Adding, perhaps, Beccaria on crimes and punishments, because of the demonstrative manner in which he has treated that branch of the subject. If your views of political inquiry go further, to the subjects of money and commerce, Smith's Wealth of Nations is the best book to be read, unless Say's Political Economy can be had, which treats the same subjects on the same principles, but in a shorter compass and more lucid manner. But I believe this work has not been translated into our language.

History, in general, only informs us what bad government is. But as we have employed some of the best materials of the British constitution in the construction of our own government, a knowledge of British history becomes useful to the American politician. There is, however, no general history of that country which can be recommended. The elegant one of Hume seems intended to disguise and discredit the good principles of the government, and is so plausible and pleasing in its style and manner, as to instil its errors and heresies insensibly into the minds of unwary readers. Baxter has performed a good operation on it. He has taken the text of Hume as his ground work, abridging it by the omission of some details of little interest, and wherever he has found him endeavoring to mislead, by either the suppression of a truth or by giving it a false coloring, he has changed the text to what it should be, so that we may properly call it Hume's history republicanised. He has moreover continued the history (but indifferently) from where Hume left it, to the year 1800. The work is not popular in England, because it is republican; and but a few copies have ever reached America. It is a single quarto volume. Adding to this Ludlow's Memoirs, Mrs. M'Cauley's and Belknap's histories, a sufficient view will be presented of the free principles of the English constitution.

To your request of my opinion of the manner in which a newspaper should be conducted, so as to be most useful, I should answer, "by restraining it to true facts and sound principles only." Yet I fear such a paper would find few subscribers. It is a melancholy truth, that a suppression of the press could not more completely deprive the nation of its benefits, than is done by its abandoned prostitution to falsehood. Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle. The real extent of this state of misinformation is known only to those who are in situations to confront facts within their knowledge with the lies of the day. I really look with commiseration over the great body of my fellow citizens, who, reading newspapers, live and die in the belief, that they have known something of what has been passing in the world in their time; whereas the accounts they have read in newspapers are just as true a history of any other period of the world as of the present, except that the real names of the day are affixed to their fables. General facts may indeed be collected from them, such as that Europe is now at war, that Bonaparte has been a successful warrior, that he has subjected a great portion of Europe to his will, &c., &c.; but no details can be relied on. I will add, that the man who never looks into a newspaper is better informed than he who reads them; inasmuch as he who knows nothing is nearer to truth than he whose mind is filled with falsehoods and errors. He who reads nothing will still learn the great facts, and the details are all false.

Perhaps an editor might begin a reformation in some such way as this. Divide his paper into four chapters, heading the 1st, Truths. 2d, Probabilities. 3d, Possibilities. 4th, Lies. The first chapter would be very short, as it would contain little more than authentic papers, and information from such sources, as the editor would be willing to risk his own reputation for their truth. The second would contain what, from a mature consideration of all circumstances, his judgment should conclude to be probably true. This, however, should rather contain too little than too much. The third and fourth should be professedly for those readers who would rather have lies for their money than the blank paper they would occupy.

Such an editor too, would have to set his face against the demoralizing practice of feeding the public mind habitually on slander, and the depravity of taste which this nauseous aliment induces. Defamation is becoming a necessary of life; insomuch, that a dish of tea in the morning or evening cannot be digested without this stimulant. Even those who do not believe these abominations, still read them with complaisance to their auditors, and instead of the abhorrence and indignation which should fill a virtuous mind, betray a secret pleasure in the possibility that some may believe them, though they do not themselves. It seems to escape them, that it is not he who prints, but he who pays for printing a slander, who is its real author.