полная версия

полная версияThe Common Objects of the Country

Fortunately, toads had two livers; and although both of them were corrupted, yet one was full of poison, and the other resisted poison. As for remedies, the only effectual one was of rather a complicated nature, and consisted of plantain, black hellebore, powdered crabs, the blood of the sea-tortoise mixed with wine, the stalks of dogs’ tongues, the powder of the right horn of a hart, cummin, the vermet of a hare, the quintessence of treacle, and the oil of a scorpion, mixed and taken ad libitum.

THE COMMON TOAD.

Even in the days when this prodigious prescription was invented, some good was acknowledged to exist in a toad, the one being the precious jewel in its head, and the other its power as a styptic. Supposing any one to fall down and knock his nose against a stone, he could instantly stop the bleeding if he only had in his pocket a toad that had been pierced through with a piece of wood and dried in the shade or smoke. All that was requisite was to hold the dried toad in the hand, and the bleeding would immediately cease. The reason for this effect is, that “horror and fear constrained the blood to run into his proper place, for fear of a beast so contrary to humane nature”.

And, as a concluding instance of the wonderful things that happened whenever toads were the subject, we are told that at Darien, where the household slaves water the door-steps in the evening, all the drops that fall on the right hand turn into toads.

These poor creatures fare little better even now, as far as public opinion goes; and in France worse than in England.

I was once walking in the forest at Meudon with a party of friends, and was brought to a check by a sudden attack made on a large toad that was walking along the pathway. I succeeded in stopping a blow that was aimed at it; and was stooping down, intending to remove it to a place of safety, when I was hastily pulled away, and horror was depicted on the countenances of all the spectators.

“It will bite you,” cried one.

“Pouah!” exclaimed another, “it will spit poison at you.”

“In France, every one kills toads,” said a third.

I objected that it could not bite, because it had no teeth.

“No teeth!” they all exclaimed. “In France, toads always have teeth.”

“Well, then,” I said, “I will open its mouth, and show you that it has none.”

But before I could touch it I was again dragged away.

“Teeth come when the toads are fifty years old,” was the explanation that was given; but still the death-sentence had passed in every mind, and I knew that when I moved the poor toad would be killed.

Just then, some one remarked that tobacco killed toads, if put on their backs. So I took advantage of the assertion, and made a compromise that, on my part, I would not handle the toad; and that, on theirs, the only mode by which they might kill it was by putting tobacco on it.

The terms being thus arranged, plenty of tobacco was produced—and very bad tobacco, too, as is generally the case in France; and, as no one but myself dared come so near, I put about half-an-ounce of the weed on the back of the toad, as it sat in a rut. For a minute or more, the creature sat quite still, and all the party began to exclaim:—

“See! the toad is quite dead!”

“Ah! the nasty animal!”

“Monsieur Ool!—(no one ever made a better shot at my name than Ool)—Monsieur Ool! the toad is dead!”

However, the toad rose, shook off all the tobacco, and recommenced his march along the road. The only good that was done was the saving of that individual toad’s life, for all the party retained their faith in toads’ teeth, and probably thought that the creature would not touch me because I was a trifle madder than the rest of my nation, who are always very mad on the French stage.

Afterwards, I found that the belief in toads’ teeth was quite general; and one person offered to show me some, half-an-inch in length, which he kept in a box at home. But I was never fortunate enough to see them.

In England, toads are sometimes valued for the good which they do; and the market-gardeners, whose trim grounds surround London, actually import toads from the country, paying for them a certain sum per dozen. For toads are voracious creatures, feeding upon slugs, worms, grubs, and insects of various kinds, and so devour great numbers of these little pests to the gardener.

The mode in which a toad catches its prey is curious enough. Its tongue is fastened into its mouth in a very peculiar way, the base of the tongue being fixed at the entrance of the mouth, the tip pointing down its throat when it is at rest. When, however, the toad sees an insect or slug within reach, the tongue is suddenly shot out of the mouth, and again drawn back, carrying the creature with it.

So rapidly is this operation performed, that the insect seems to disappear by magic. The frog feeds in the same manner.

For the poisonous properties attributed to the toad, there is some foundation, though a small one. But a very small foundation is generally found strong enough to bear a very large superstructure of calumny; though the reverse is the case when the report is a favourable one. The skin of the toad is covered with small tubercles, which secrete an acid humour sufficiently sharp and unpleasant to prevent dogs from carrying a toad in their mouths, though not so powerful as to deter them from attacking toads and killing them.

A rather curious advantage has been taken of the insect-eating propensities of the toad. A gentleman had killed a toad at a very early hour one morning, and after skinning it, for the purpose of stuffing the skin, he dissected its digestive system. The contents of the stomach he turned out into a basin of water, and found there a mass of insects, some of them very rare and in good preservation.

Afterwards, he was accustomed to kill toads for the express purpose of collecting the insects that were found within them, and which, being caught during the night, were often of such species as are not often found.

The same experiment elicited another curious fact, namely, the great tenacity of life possessed by some insects. Before pinning out the insects that were found, and which were mostly beetles, they had been allowed to remain in the water for several days, and were apparently dead. Yet, when they were pinned on cork, they revived; and, when they were visited, were found sprawling about in quite a lively style.

Like all the reptiles, the toad changes its skin, but the cast envelope is never found, although those of the serpents are common enough. The reason why it is not found is this: the toad is an economical animal, and does not choose that so much substance should be wasted. So, after the skin has been entirely thrown off, the toad takes its old coat in its two fore-paws, and dexterously rolls it, and pats it, and twists it, until the coat has been formed into a ball. It is then taken between the paws, pushed into the mouth, and swallowed at a gulp like a big pill.

CHAPTER IV

NEWTS—A FISH WITH LEGS—NEWTS FEEDING—NEWT-CANNIBALS—CASTING THE SKIN—STRANGE STORIES—ANOTHER NEWT STORY—HATCHING OF YOUNG—TENACITY OF LIFE—THE STICKLEBACK—ITS PUGNACITY—ITS COLOURS—ACCLIMATISATION—THE LAMPERN—A RUSTIC PHILOSOPHER—THE CRAY-FISH—HOW WE CAUGHT IT—REPRODUCTION OF LIMBS—FRESH-WATER SHRIMP—WOODLOUSE AND ARMADILLO.

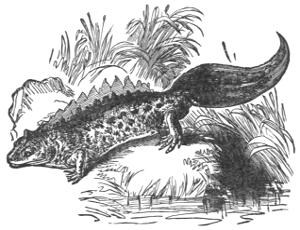

The Newts, or Efts, or Evats, as they are called in different parts of England, can be easily distinguished from the lizard by the flattened tail, which, being intended for swimming, is formed accordingly.

THE COMMON NEWT.

Two species of these creatures are found in this country, the common Water-Newt and the Smooth Newt. These beautiful creatures may be found in almost every piece of still water, from ponds and ditches up to lakes. The full beauty of the newt is not seen until the breeding season begins to come on, and even then only in the male.

At this time the green back and orange belly attain a brighter tint, and the back is decorated with a wavy crest, tipped with crimson. This crest is continually waving from side to side as the creature moves, and forms graceful curves. The newts are equally at home in water and on land, and in the latter case have often been mistaken for lizards.

One of these animals, when taking a walk, alarmed an acquaintance of mine sadly. He was rather a tall man than otherwise, and did not appear particularly timid; but one day he came to me looking somewhat pale, and announced that he had just been terribly frightened.

“A fish, with legs!” said he, “four legs! got out of the water and ran right across the path in front of me! I saw it run!”

“A fish with legs!” I replied; “there are no such creatures.”

“Indeed there are, though, for I saw them. It had four legs, and it waggled its tail! It was horrible, horrible!”

“It was only a newt,” I replied, “an eft. There is nothing to be afraid of.”

“It was the legs,” said he, shuddering, “those dreadful legs. I don’t mind getting bitten, or stung, but I can’t stand legs.”

Newts are very interesting animals, though they have legs, and can easily be kept in a tank if fed properly. Little red worms seem to be their favourite food, and the newt eats them in a rather peculiar style. I have had numbers of newts of all sizes and in all stages of their growth, and always found them eat the worm in the same way. As the worm sank through the water, the newt would swim to it, and by a sudden snap seize it in the middle. For nearly a minute it would remain with the worm in its mouth, one end protruding from each side of its jaws. Another snap would then be given, and after an interval a third, which generally disposed of the worm.

When they have been swimming freely in a large pond, I have often seen large newts attack the smaller, and try to eat them; but I never saw the attempt successful, though I hear that they have been seen to devour the younger individuals. They always came from behind, as if trying to avoid observation, and then made a sudden dart forward, snapping at the tail of their intended victim. In confinement I never saw even an attempt at cannibalism.

Whether it is invariably the case I cannot say, but every newt that I took cast its skin within a few hours from the time that it was placed in the glass jar. The general surface of the skin came off in flakes, but that from the paws was drawn off like gloves, retaining on their surface all the markings and creases which they exhibited when in their proper place.

How the drawing off of their tiny gloves was effected I could not see, though I watched carefully. They looked beautiful as they floated in the water, being delicate as gossamer, white, and almost transparent. They might have been made for Queen Mab herself, and were so delicate that I never could preserve any of them so as to give a proper idea of their form.

It may be that the change of water might cause the change of skin, for the water in which they were kept was drawn from a pump, and that in which they formerly lived was the ordinary soft water found in ponds.

Pretty as is the newt, it is as harmless as pretty, and notwithstanding has suffered under the reputation of being a venomous creature. The absurd tales that I have heard of this creature could scarcely be believed; and how people with any share of sense could receive such absurdities is matter of wonder. And as usual, the moral of the stories is, that newts are to be killed wherever found. The belief of the poisonous character of the newt is of long standing, as may be seen in the ancient works on natural history. In one of these it is said that its poison is like that of vipers; and there is a description of the formation of its tail which is rather beyond my comprehension:—

“The tail standeth out betwixt the hinder-legs in the middle, like the figure of a wheel-whisk, or rather so contracted as if many of them were conjoined together, and the void or empty places in the conjunctions were filled”.

The capture and domesticating of newts gave dire offence in the village where I lived for some time; and the expressions used when I took a newt in my hands were not unlike those of the Parisians respecting the toad. Sundry ill-omened tales of effets were told me. For example: A girl of the village was filling her pitcher at a stream which runs near the village, when an effet jumped out of the water, sprang on her arm, bit out a piece of flesh, spat fire into the wound, and, leaping into the water, escaped. The girl’s arm instantly swelled to the shoulder, and the doctor was obliged to cut it off.

This was told me with an immensity of circumstantial details common to such narrators, and was corroborated by the bystanders. The wounded lady herself was not to be found, and cross-questions elicited that it “weir afoor their time”. I asked them how the effet which lived in the water, and had just leaped out of it, was able to keep a fire alight in its interior; but they were not in the least shaken, except perhaps in their heads, which were wagged with a Lord Burleigh kind of emphasis.

Then there was the sexton-clerk-gardener-musician and general factotum, who had a newt tale of his own to tell. He had been cutting grass in the churchyard, and an effet ran at him, and bit him on the thumb. He chopped off the effet’s head with his knife, but his thumb was very bad for a week.

Once they got the better of the argument, at all events in the eyes of the owner of the farming stock, and my poor newts were ejected. It happened thus:—

Two or three specimens I kept in my own room in a glass vase, in order to watch them more closely; and some six or seven others lived as stock in the large horse-trough, from whence they could be taken when required.

One day the proprietor came to me and ordered the destruction of my newts, for they had killed one of his calves.

“But,” I remonstrated, “they cannot kill a calf or even a mouse, for they have no fangs and very little mouths. Besides, the calf has not come near this trough.”

So saying, I took up several of the newts, opened their mouths—no easy matter, by the way—and showed that they had no fangs. And I urged, that even if they had been as poisonous as rattlesnakes, it would not have made any difference to the calf, which had never left the cowhouse, and was at the opposite end of the farm-yard, separated by a barn and several gates. But all was useless.

“There are the newts, and there is the dead calf!” was the answer; and so the newts had to go. However, I would not suffer them to be killed, but put them into a bag and took them back to the pond whence they had come.

Afterwards the proprietor said that the calf died because its mother had drunk at the trough in which the poisonous newts were.

Now, the funniest part of the story is, that there was not a horse-pond that did not swarm with efts, and consequently all the foals and calves ought to have died. Only they didn’t.

The care which the female newt takes in depositing her eggs is very remarkable.

THE FEMALE NEWT.

Each egg is taken separately, and by the aid of the fore-paws is regularly tied or twisted up in the leaves of dead plants, for which process different people have different reasons. Some think that it is for the purpose of preventing too ready an access of water, and so to retard their hatching; while some say that it is to guard the egg against voracious water-animals. To the latter opinion I rather incline; perhaps both may be right.

When hatched, the young newt is very like a tadpole, breathing by gills outside its neck. After a while the gills vanish and the legs appear; but it keeps its tail. It is rather curious that the frog tadpole puts forth its hinder-legs first; while in the tadpole of the newt, the fore-legs are the first to show themselves.

After the gills are lost, the newt breathes by means of lungs; and if it is in the water, is forced to rise at intervals for the purpose of breathing.

The tenacity with which these creatures cling to life is quite surprising. Experiments have been tried purposely to see to what degree a body could be mutilated, and yet retain life. They have even been frozen up into a solid block of ice, and, after the thawing of their cold prison, revived, and seemed none the worse for it. I may as well mention that none of these experiments were tried by myself, for I am not scientific enough to care nothing for the infliction of pain; but on one occasion I did try an experiment, and, as it turned out, a very cruel one, although it was not intended for an experiment.

I was studying the anatomy of the frogs and newts; and having eight or ten fine specimens of the latter creature, determined to take advantage of the opportunity. The first thing was, of course, to kill the creature without injuring its structure, and I thought that the best mode of so doing would be to put it into my poison-bottle. This was a large glass jar filled with spirits of wine, in which was held corrosive sublimate in solution. This mixture generally killed the larger insects almost immediately, and seemed just the thing for the newts.

So they were put into the jar—but then there was a scene which I will not describe, which I trust never to see again, and of which I do not even like to think. Suffice it to say, that nearly a quarter of an hour elapsed before these miserable creatures died, though in sheer mercy I kept them pressed below the surface.

Changing our post of observation from the banks of the ponds to those of the running streams, we shall find there many creatures worthy of observation; so many, indeed, that it would be a hopeless task to attempt to give even a slight account of one-fiftieth of them. I shall, therefore, only mention two creatures, as examples of the fish; and these two are chosen because they are exceedingly common, and very different from each other in colour and habits.

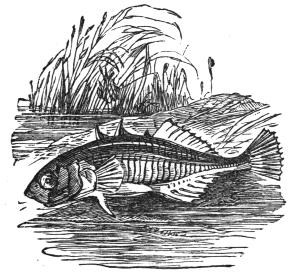

The first of these creatures is the common Stickleback, or Tittlebat, as it is sometimes called. There are several species of British sticklebacks; but the commonest, and I think the most beautiful, is the three-spined stickleback.

These little fish derive their name from the sharp spines with which they are armed, and which they can raise or depress at pleasure—as I know to my cost. For being, as boys often are, rather silly, I made a wager that I would swallow a minnow alive; and having made the bet, proceeded to win it. Unfortunately, instead of a minnow, a stickleback was handed to me, which having its spines pressed close to the body, was very like a minnow. Just as I swallowed it, the creature stuck up all its spines, and fixed itself firmly.

THE STICKLEBACK.

Neither way would it go, and the torture was horrid. At last, a great piece of apple that I swallowed gave it an impetus that started it from its position; but it was not for some time, that to me appeared hours, that the fish was disposed of. And even then it left its traces; and if it would be any satisfaction to the fish to know that ample vengeance was taken for its death, it must have been thoroughly gratified.

There are few fish more favoured in point of decoration than the stickleback; although the decoration, like that of soldiers, is only given to the gentlemen, and of them only to the victors in fight.

They are most irritable and pugnacious creatures, that is, in the early spring months, when the great business of the nursery is in progress. And the word nursery is used advisedly; for the stickleback does not leave her eggs to the mercy of the waters, but establishes a domicile, over which her husband keeps guard.

The vigilance of this little sentry is wonderful; and I have often seen fierce fights taking place. Not a fish passes within a certain distance of the forbidden spot, but out darts the stickleback like an arrow, all his spines at their full stretch, and his body glowing with green and scarlet. So furious is the fish at this time that I have sometimes amused myself by making him fight a walking-stick.

If the stick were placed in the water at the distance of a yard or so, no notice was taken. But as the stick was drawn through the water, the watchful sentinel issued from his place of concealment, and when the intruding stick came within the charmed circle, the stickleback shot at it with such violence that he quite jarred the stick.

His nose must have suffered terribly. If the stick were moved, another attack would take place, and this would be continued as long as I liked.

Sometimes a rival male comes by, with all his swords drawn ready for battle, and his colours of red and green flying. Then there is a fight that would require the pen of Homer to describe. These valiant warriors dart at each other; they bite, they manœuvre, they strike with their spines, and sometimes a well-aimed cut will rip up the body of the adversary, and send him to the bottom, dead.

When one of the combatants prefers ignominious flight to a glorious death, he is pursued by the victor with relentless fury, and may think himself fortunate if he escapes.

Then comes a curious result. The conqueror assumes brighter colours and a more insolent demeanour; his green is tinged with gold, his scarlet is of a triple dye, and he charges more furiously than ever at intruders, or those whom he is pleased to consider as such. But the vanquished warrior is disgraced; he retires humbly to some obscure retreat; he loses his red, and green, and gold uniform, and becomes a plain civilian in drab.

Sometimes I have brought on a battle royal between the guardians of several palaces, by dropping in the midst of them a temptation which they could not resist. This was generally a fine fat grub taken from a caddis case. The caddis is large and white, and so can be seen to a considerable distance.

As this sank in the water, there would be a general rush at it, and the ensuing contention was amusing in the extreme. First, one would catch it in his mouth and shoot off; half-a-dozen others would unite in chase, overtake the too fortunate one, seize the grub from all sides, and tug desperately, their tails flying, their fins at work, and the whole mass revolving like a wheel, the centre of which was the caddis worm.

It would be swallowed almost immediately, but the mouth of the stickleback is much too small to admit an entire caddis, and the skin of the grub is too tough to be easily pierced or torn. Half-an-hour often elapses before the great question is settled, and the caddis eaten.

The rapidity of the evolutions and the fierceness of the struggle must be seen to be appreciated—and it is a spectacle easily to be witnessed; wherever there are sticklebacks, caddis worms are nearly certainly found, and it only needs to extract one of these from its case and deposit it judiciously in the water.

The stickleback is a hardy little fish, and can easily be kept in the aquarium, if plenty of room be given to it. It has even been trained to live in seawater, by adding bay-salt to the water in which it dwelt; so that the plan of pickling salmon alive, by a judicious admixture of vinegar and allspice with the water, has something to which to appeal as collateral evidence.

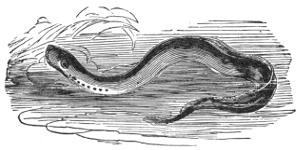

The other representative of the fishes is a very curious one, and can be easily observed. It is called the “Lampern,” and is shown in the accompanying figure.

THE LAMPERN.

In some parts of England the lampern goes by the name of “Seven-eyes,” in allusion to the row of eye-like holes that may be seen extending along the side of the throat. These apertures are the openings by which the water passes from the gills.

The chief external peculiarity in this creature is the mouth, which, instead of being formed with jaws like those of other fishes, resembles none of them, not even those of the eel, which it most resembles externally. Indeed, on looking at the mouth of a lampern, one is forcibly reminded of the leech, for it is possessed of no jaws, and adheres firmly to the skin by exhaustion of the air.