полная версия

полная версияLife and Lillian Gish

When the camera stopped, she peeped around it, the tears still shining in her eyelashes.

“Was that all right, Mr. Vidor? Or shall we try it again?”

“Well, let’s try it this way, too, and see how it looks,” in Mr. Vidor’s soft, lazy Southern accent.

So Mimi is unhappy this way and that way and several other ways, until she receives her scanty loan and turns slowly and goes out of the door. That was all of Mimi, for that time.

When next we saw her, it was at a picnic in the woods of “Ville D’Avray” … a place of orange groves at the foot of mountains that stretch up into the lofty snow fields.

In a grassy meadow, sheltered by oak trees, the picnic was spread. Miss Gish’s town car, with its shades drawn, was already parked at one side. Through the back window of an expensive coupé, a black head swathed in a towel indicated the transformation of John Gilbert into Rodolphe....

When Miss Gish stepped out of her car and began to work, it was like the arrival of a limpid, fragrant wood elf, so exquisite was her costume and so beautiful was she herself....

When I start to write of Mimi as I last saw her, I am reminded of the sensations I had as a child, when Mother used to tell me in vain that whatever I was reading was only a play or a story.... Thus I keep assuring myself that Miss Gish is a young lady who makes enough money to live on very comfortably, and that she has beauty, fame and adoring friends.

Yet there keeps recurring the picture of our last work in “La Bohême,” of the dying Mimi, struggling across Paris to Rodolphe. Her miserable clothes are in rags, and illness has carved deep hollows in her face. Clinging to the steps of a bus, fighting weakly through crowds, falling into the gutter and crawling on upon hands and knees, dragged holding to a chain behind a cart, slowly making her way, her long, pale-gold hair falling down over her shoulders and back.

Between shots you might have thought her still playing a bit in the picture, so unpretentious was her manner. If her skirt had to be dirty for a close shot, she did not hail a prop boy, but knelt on the cobblestones and made it grimy herself....

Toward the end of the sequence—scratched and bruised from her numerous falls and tumbles, her clothes ragged and mud-stained, her beautiful hair tangled and dusty, she waited so patiently for the lights to be arranged for each shot, now standing on the rough, sharp cobbles, now collapsed on the step. Sitting in the gutter, waiting for Mr. Vidor’s signal, she smoothed her apron—a tattered piece of black cotton—with a delicate gesture.

The preservation of an illusion through reality is always a feat, an illusion being of such a fragile, rarefied substance. Usually we learn to be satisfied with treasured remnants. Thus, it is with pride in my good fortune, and with gratitude to Lillian for being what she is, that I present to you an illusion, not only intact but even increased in value—Miss Gish!

With her usual thoroughness, Lillian had prepared for the difficult rôle of Mimi, especially for the tragic end. Mimi’s illness was a malady of the lungs, brought on through exposure, hunger and unremitting toil. Before the great death scene, Lillian had gone to see a priest about getting a chance to study the progress of the disease. Most of the priests knew her, after “The White Sister,” and this one was especially kind. He took her to the County Hospital. All were proud and eager to help her. They told her the symptoms at the different stages. It was all rather terrible.

Both Miss Moir—Miss Gish’s secretary—and Mr. Vidor, in letters to the writer, have written of the result of this intense hospital study. Mr. Vidor’s picture follows:

Another episode I shall never forget: The death scene was scheduled for a certain morning, but because the set was incomplete, it was postponed till the following day. Miss Gish had not been told of this postponement, and had thought so much and concentrated so vigorously to make this scene realistic, that she arrived at the studio whiter than I had ever seen her and looking at least ten pounds thinner. She was unable to speak above a whisper; in fact, she talked very little. We tried to do other scenes, but Miss Gish had lived that death so continuously during the night before that I was unable to instill enough life into her to make any other scenes that day. This terrific concentration continued all that day and that night. Upon my arrival at the studio next morning I was informed there would be another delay until that afternoon on this particular set. Again we made quick plans to switch, but when I saw Miss Gish we cancelled them. One look at her and my fears began to rise. I began to think that if we didn’t hurry and take this death scene we should never be able to finish the picture, so thoroughly was she experiencing the tortures of a tubercular death.

“LA BOHÊME” Mimi at the pawnshop

That afternoon the set was complete and we hastened—with great solemnity, I may add—to photograph Mimi’s death. I was jammed between a camera and a slanting wall in a narrow attic corner. Mimi was carried in by her friends, the bohemians, and placed upon her little bed. After her friends had taken a last farewell, Rodolphe entered the scene, and with him close to her Mimi breathed her last. Rodolphe, played by John Gilbert, was supposed to remain in the scene a few moments and then leave. In the playing of the scene, however, some of the bohemians, and also Mr. Gilbert, were so impressed that they completely forgot what they were to do. I, myself, was in the same frame of mind.

I had noticed that when death overcame Mimi, Miss Gish had completely stopped breathing and the movement of her eyes and eyelids was absolutely suspended. This, even from the close view I had. The moments clicked but still Miss Gish had not moved, nor breathed. My mind immediately jumped to the great drama of this situation. To me, Miss Gish had actually died in the portrayal of a scene. I saw all the headlines in the newspapers of the following day. I saw all the drama and the hush that would fall throughout the studios when the news spread around.

The cameras ground on—the moments turned into minutes. Finally, after an untold length of time, the other actors left the scene and the cameras stopped. Everyone was breathless, fearful of what might have happened. Miss Gish could plainly hear that the cameras had stopped, and could now take breath and open her eyes. But this she did not do. Not daring to speak I fearfully walked over to where she lay and touched her gently on the arm. Her head turned slowly, and her lips formed a faint smile.

I think we all broke into tears of great joy.

To me this is the most realistic scene I have ever known to be enacted before a camera. I hope I shall never see a similar one quite so well done. The inside of her mouth was completely dry, and before she was able to speak again it was necessary to wet her lips which had stuck to her teeth from dryness. The next morning Miss Gish was as bright and cheery as ever, and we were able to go ahead with the rest of the picture.

One last word: personal contact with Lillian Gish did not destroy any of the idealism she created on the screen for me. To those who have known her only in that way, I promise there is no disappointment in meeting her face to face.

Miss Moir remembers that these final scenes of Mimi’s life lasted about a week, and that everyone was relieved when they were over. Lillian herself was so exhausted that her voice had sunk almost to a whisper, and she had hardly sufficient strength to walk. “Poor Renée Adorée was constantly coming back to her dressing room for a fresh supply of handkerchiefs. During the sequence where Mimi is dragging herself back to Rodolphe, to die—the bus, to the back of which she was clinging, suddenly lost a wheel, and it was only by a miracle that she escaped having both legs crushed under the heavy vehicle.”

It was near the end of December, 1925, that “La Bohême” was finished, and it was two months later, February 24, at the Embassy Theatre, New York, that it had its first showing. Lillian was not present. To this day, she has never seen “La Bohême” given with its musical accompaniment—not the original Puccini score, the cost of which was prohibitive, but a very lovely adaptation expressing something of the feeling and mood.

“La Bohême,” a picture of much sorrow and little brightness, was sympathetically received and left a deep and lasting impression. Except, possibly, in “Broken Blossoms,” Lillian had never appeared so effectively—in a picture so suited to her gifts.

It was a big night at the Embassy. Social New York was out in force, and all the picture people. The Post next day said:

“Every movie player in New York, and there are many here just now, was ‘among those present,’ for the infrequent appearance of Lillian Gish on the screen takes on the importance of an event.... The Gish can do no wrong, in the opinion of many who subscribe to the art of motion pictures....”

Approval of Lillian’s Mimi, though wide, was not unanimous. Certain critics were inclined to hold her responsible for the departure from Murger’s original. There was hot debate among the fans. Lillian, already absorbed in another picture, gave slight attention to all this; much less than did the interviewers, one of whom found her “not particularly interested.” She merely asked absently: “Has someone been criticizing me?” Which, declared Miss Glass, the interviewer, was as astonishing as if she had looked at the Pacific Ocean and asked: “Is it wet?”

“Her manifest lack of resentment toward her critics confounded me.... She sat quietly toying with the folds of her dress, betraying no sign of annoyance or concern.”

In itself, the Mimi of Madame de Grésac was a classic rôle. Not again in her screen life would Lillian find a part more perfectly suited to her personality and special gifts. Her portrayal of it warranted Pola Negri’s verdict:

“Lillian Gish is supreme. That was my opinion when I first saw her. It is still my opinion when I have seen all the other stars. She is sublime in her genre.”

The New York première was not the picture’s first showing. There had been a preview at Santa Monica, and one secured by Lillian for the employees of the Beverley Hills Hotel, where she lived. These latter sent her a joint acknowledgment, signed: “Thankfully your admirers, more than a hundred strong.”

VI

“THE SCARLET LETTER”

Lillian had not found time to go to New York. Through no fault of hers, the production of “La Bohême” had been delayed, and there was not a moment to lose, now. “La Bohême” was finished on Saturday, and the first shots of “The Scarlet Letter” were made the following Monday. She had agreed to do as many as six pictures, and she had two years to do them in. She was very anxious to fulfill her part of the contract.

Her mother was with her. She had come out with her in May, but in September had gone back to London, where Dorothy was making “Nell Gwynn” for an English company. Now again she was back, vainly, unwisely trying to share herself with both daughters. In January, Lillian had taken Mrs. Pickford’s house at Santa Monica, directly on the beach. She believed it would be better for her mother—not always warm, but there was nearly always sunshine, and the air was good.

Every morning Lillian went into the sea. The water was cold, but by six she had put on her bathing suit, and plunged in. A dip, then out again, a race to the house, a cup of hot water that Nellie, the maid, had ready. Then quickly into a little roadster and away to the Culver City lot, a brisk twenty-minute drive. Nellie there prepared breakfast while her mistress was dressing and making up.

In her little corner of Beekman Terrace, the “den,” as she calls it, overlooking the East River where a procession of water traffic moves always up and down—stout, saucy tugs, with square-nosed barges or droopy, submissive schooners in tow; swift Sound steamers; smudgy freighters; private yachts—very romantic and expensive-looking; all the motley parade of the marine register—Lillian not so long ago told of the making of “The Scarlet Letter.” She said:

“It was while we were making ‘La Bohême’ that I worked with Frances Marion on the story. Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne appealed to me, and I thought the story had great picture possibilities. There was one objection: the Church would oppose it—the Protestant Church, especially the Methodist. ‘The Scarlet Letter’ was one of a list of proscribed books—forbidden for picture use. I took the matter up with Will Hays, and prominent members of the Clergy. Why should the Church prohibit a great classic, like that? When I told them how I proposed to present it, they gave their sanction. When they saw the picture, by and by, they recommended it.

“My idea was to present Hester as the victim of hard circumstance, swept off her feet by love. Of course, that was what she was, but her innate innocence must be apparent. I said:

“I believe in ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ if we can get the right man for Dimmesdale, the minister.” We considered several, but none would do.

“One day, Louis B. Mayer, business head of the Metro, said to me: ‘I think I have found the minister for your “Scarlet Letter.”’ Mayer had brought over Greta Garbo, and I had faith in him. Garbo had done a picture of ‘Gosta Berling’ in Sweden, with Lars Hansen, and the Metro had brought over a print of it. ‘Go into the projection room and have them run it for you,’ said Mayer. ‘If you like Hansen for the part, we’ll bring him over.’

“The moment Lars Hansen appeared on the screen, I knew he was the man we wanted. And I knew that we must have a Swedish director. The Swedish people are closer to what our Pilgrims were, or what we consider them to have been, than our present-day Americans. Irving Thalberg selected Victor Seastrom, a splendid choice. He got the spirit of the story exactly, and was himself a fine actor, the finest that ever directed me. I never worked with anyone I liked better than Seastrom. He was Scandinavian—thorough and prompt. If Mr. Seastrom said we would start at eight, or half-past, the camera was ready at that time, and so were we.

“His direction was a great education for me. In a sense, I went through the Swedish school of acting. I had got rather close to the Italian school in Italy, watching them at their theatres, and from being associated with those who were with us in ‘The White Sister’ and ‘Romola.’ The Italian school is one of elaboration; the Swedish is one of repression. Mr. Vidor’s method—of the American school, if there is such a thing—leaned to self-expression, which has its advantages.

“We had some of the people used in ‘La Bohême’—Karl Dane, for one, who, except for the brief scene where a scrap of my forbidden laundry creates a situation and finally flares out on a currant bush—furnished about all the comedy of that too sad picture. Henry B. Walthall, with whom I had played so often in the old Griffith days, was engaged to do Prynne, Hester’s husband. In the old days, he had been taller than I was. I was amazed now to find it the other way about. I had grown a good deal in the ten or eleven years since then. I suppose exercise, open air, health and proper food, had been responsible. Joyce Coad, my little girl in the play, was a sweet child, and a clever little actress. I became much attached to her.

“Work on ‘The Scarlet Letter’ went off smoothly until we were within two weeks of the end. Then, one day in April, I got a paralyzing cable from Dorothy in London. Dorothy had been over for a brief visit during the Winter, and Mother had presently followed her back to London. She had not wanted to go—not really. She had not been well for years. Commuting back and forth across six thousand miles, trying to be with both of us, had been too much for her. That last time she would not let me go to the train with her. Dorothy’s cable said that she was dying.

“I cabled and got the latest news of her; she had had a stroke. I said I would take the first ship I could get from New York.

“I found that by leaving Los Angeles in three days, I could catch the Majestic out of New York, which would put me in London the last day of April. It was the 15th that she had been struck down.

“At the studio, Seastrom said that by working day and night we could do the remaining two weeks on the picture in the three days I had left. I asked the company if they would stay with me through it, and every one said yes. They were all so fine.

“We didn’t waste a moment, and during those three days and nights there was very little sleep for anyone. I remember scarcely anything of the details, for of course I had Mother on my mind, too. When the last scene was shot, I made a rush for the train, without stopping to change from my costume. Mr. Mayer and Mr. Thalberg got special police on motorcycles to escort me and clear the way, so that I could work to the last moment and still get the train. Twelve days later I was in London.”

Characteristically, Lillian says nothing of that trip across land and sea. Miss Moir, less reticent, writes:

I shall always remember the kindness and sympathy shown her during those long wearisome days on the train … the little Catholic girl at Albuquerque who somehow or other managed to find her way to our compartment and press into Lillian’s hand a little silver cross which she said had been specially blessed and would surely bring an answer to her prayers for her mother.

… At Topeka, Kansas, when the train pulled in, we noticed that the platform was jammed from end to end with people. We supposed that they must have come to welcome someone and pulled down the blinds in the compartment to escape notice. Suddenly we heard raps on the window and calls for Miss Gish. The conductor appeared, smiling, to say that all these people had come to see Miss Gish, some of them had even driven a hundred miles for the purpose. Tired and heartsick as she was, Lillian went out on the platform of the train. The moment she appeared, a sudden silence fell on the crowd—they just stood and looked at her. Then a woman held up a baby and asked her to touch it “for luck.” That broke up the formality. They crowded round her, expressing their sympathy and good wishes, and they were still in the midst of it when the train pulled out leaving them cheering and waving.

We arrived in New York on the morning of the day the Majestic sailed. When, late that night we went on board the boat, we found our stateroom filled with people all waiting to see Lillian.

One pleasant young man with an ingratiating smile, insisted upon bringing in his girl-friend to meet Lillian, who, tired as she was, still managed to smile at them.

In London, Lillian learned just what had happened: Dorothy had been out to a play, and had come in quietly and slipped into bed without turning on the light. Mrs. Gish slept in the other twin bed. Presently, Dorothy felt something touch her. She spoke softly, but got no answer. She felt the touch again, and again got no answer. The third time, she snapped on the light. Her mother could not speak—all her right side was helpless. Fortunately, Dorothy’s bed had been at her left.

With Lillian’s arrival Mrs. Gish improved. Only the day before she had not been expected to live. She seemed to recognize her—her eyes grew large. Every paper had displayed in headlines Lillian’s race across the world to her mother’s bedside, and the English are a kindly people. Noble and commoner alike came forward with offered help—all ranks knew and loved her. Cards, flowers, gifts, poured in.

What was to be done next? Lillian must return to California, or cancel her contract. What must she—what could she—do? Miss Moir tells what happened:

One night somebody suggested going to a famous little restaurant in the Tottenham Court Rd. district for dinner. So Dorothy, Lillian and I got into a taxi and drove to it, three very forlorn females.... It was over that dinner that Lillian came to what seemed at first her preposterous decision to take her mother back with her to California, but as usual, she carried her point, and within a week Mrs. Gish, with a good English doctor and nurse in attendance, Lillian and I, were all aboard the Mauretania en route for New York.

Mrs. Gish bore the journey much better than we had expected and the days passed quickly. The morning we arrived at Quarantine Lillian and I were sitting up in bed eating breakfast when our stewardess rushed in looking quite alarmed, to warn us to bolt all the doors as our stateroom was shortly to be stormed by a mob of reporters.

Lillian herself told of the hectic overland journey:

“In New York I chartered a private car and took Mother to Hollywood. I was no longer so poor, and if ever there was a time when I was thankful for money it was then. Across the blazing southern desert we had tubs of ice, with fans going over them, night and day. The car was cool, and the change, or the thought that she was going back to California, which she always loved, was good for Mother. When we reached California, instead of being on her back, she was sitting up. But she could not speak—she knew all that we said to her, but she could not answer, and she could no longer read. We were told that this condition might last three to six months. That was five years ago. She has improved a great deal; she can walk a little, but most of her right side is helpless, and her words are very limited.

“At Santa Monica we lived in Mrs. Pickford’s house until September, then moved up to the beautiful Millbank place on the cliff, with a lovely garden, and all, away from the dampness and the sound of the waves, which made Mother nervous. On her birthday, September 16, she seemed suddenly to pick up, and we felt there was a chance for her to get well.

“She does not suffer, but must get very tired of always being obliged to sit, or lie down. But she is sweet and patient. The nurse and I read to her, and she enjoys working the picture puzzles, of which she has always a supply. She likes motion picture magazines. She cannot read them, but she loves the illustrations—many of them of people she knows. And always, if the name ‘Gish’ is on any printed page, she can find it.”

“The Scarlet Letter” had its première in August, 1926, at the Central Theatre, New York City. The evening Sun next day, among other things, said:

Miss Gish, for the first time in the memory of the oldest inhabitant of the cinema palaces, plays a mature woman, a woman of depth, of feeling and wisdom and noble spirit.... She is not Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne, but she is yours and mine, and she makes ‘The Scarlet Letter’ worth a visit.

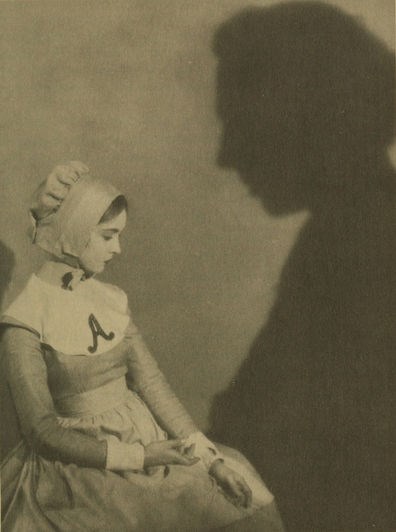

The Sun man’s notice was a fair sample of other printed opinions at home and abroad. Critics who were anxious to show that they were familiar with Hawthorne, sometimes worked themselves up over the departure from the original story, and sometimes “took it out” on Lillian and Lars Hansen, but generally they had only good things to say of the acting of these two, of little Joyce Coad and the others, and of Seastrom’s fine direction. Seastrom had created New England atmosphere on a Culver City lot, a fact not always suspected. Lillian had hoped that some of the scenes might really be made in New England, but Seastrom’s imagination had served as well—perhaps better. No fault was found here—indeed, very little anywhere. Critics who went prepared to do their worst, forgot all about it when they saw Lillian in her little Puritan cap, her expressive back in its little Puritan waist, and especially when she sat in the stocks, “for running and playing on ye Sabbath,” leaning feverishly out to drink from the cup of cold water brought her by the conscience-stricken minister. One hardened critic wrote:

I retire from the field with tears in my eyes and rage in my heart, as becomes a cynic betrayed and undone. To consider her critically is beyond my powers—she simply annihilates the instinct. Of this much I am quite sure: She is a great, a very great artist, and by far the most appealing and human little figure appearing on the screen today—and the loveliest.

“THE SCARLET LETTER” Miss Gish as Hester Prynne, with the shadow of Lars Hansen, as Dimmesdale