полная версия

полная версияAratra Pentelici, Seven Lectures on the Elements of Sculpture

200. But if you have this sympathy to give, you may be sure that whatever he does for you will be right, as far as he can render it so. It may not be sublime, nor beautiful, nor amusing; but it will be full of meaning, and faithful in guidance. He will give you clue to myriads of things that he cannot literally teach; and, so far as he does teach, you may trust him. Is not this saying much?

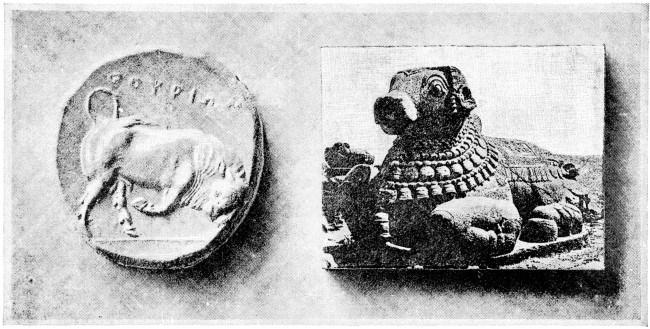

And as he strove only to teach what was true, so, in his sculptured symbol, he strove only to carve what was—Right. He rules over the arts to this day, and will forever, because he sought not first for beauty, not first for passion, or for invention, but for Rightness; striving to display, neither himself nor his art, but the thing that he dealt with, in its simplicity. That is his specific character as a Greek. Of course every nation's character is connected with that of others surrounding or preceding it; and in the best Greek work you will find some things that are still false, or fanciful; but whatever in it is false, or fanciful, is not the Greek part of it—it is the Phœnician, or Egyptian, or Pelasgian part. The essential Hellenic stamp is veracity:—Eastern nations drew their heroes with eight legs, but the Greeks drew them with two;—Egyptians drew their deities with cats' heads, but the Greeks drew them with men's; and out of all fallacy, disproportion, and indefiniteness, they were, day by day, resolvedly withdrawing and exalting themselves into restricted and demonstrable truth.

201. And now, having cut away the misconceptions which incumbered our thoughts, I shall be able to put the Greek school into some clearness of its position for you, with respect to the art of the world. That relation is strangely duplicate; for, on one side, Greek art is the root of all simplicity; and, on the other, of all complexity.

On one side, I say, it is the root of all simplicity. If you were for some prolonged period to study Greek sculpture exclusively in the Elgin room of the British Museum, and were then suddenly transported to the Hôtel de Cluny, or any other museum of Gothic and barbarian workmanship, you would imagine the Greeks were the masters of all that was grand, simple, wise, and tenderly human, opposed to the pettiness of the toys of the rest of mankind.

XX.

GREEK AND BARBARIAN SCULPTURE.

202. On one side of their work they are so. From all vain and mean decoration—all wreak and monstrous error, the Greeks rescue the forms of man and beast, and sculpture them in the nakedness of their true flesh, and with the fire of their living soul. Distinctively from other races, as I have now, perhaps to your weariness, told you, this is the work of the Greek, to give health to what was diseased, and chastisement to what was untrue. So far as this is found in any other school, hereafter, it belongs to them by inheritance from the Greeks, or invests them with the brotherhood of the Greek. And this is the deep meaning of the myth of Dædalus as the giver of motion to statues. The literal change from the binding together of the feet to their separation, and the other modifications of action which took place, either in progressive skill, or often, as the mere consequence of the transition from wood to stone, (a figure carved out of one wooden log must have necessarily its feet near each other, and hands at its sides,) these literal changes are as nothing, in the Greek fable, compared to the bestowing of apparent life. The figures of monstrous gods on Indian temples have their legs separate enough; but they are infinitely more dead than the rude figures at Branchidæ sitting with their hands on their knees. And, briefly, the work of Dædalus is the giving of deceptive life, as that of Prometheus the giving of real life; and I can put the relation of Greek to all other art, in this function, before you, in easily compared and remembered examples.

203. Here, on the right, in Plate XX., is an Indian bull, colossal, and elaborately carved, which you may take as a sufficient type of the bad art of all the earth. False in form, dead in heart, and loaded with wealth, externally. We will not ask the date of this; it may rest in the eternal obscurity of evil art, everywhere, and forever. Now, beside this colossal bull, here is a bit of Dædalus-work, enlarged from a coin not bigger than a shilling: look at the two together, and you ought to know, henceforward, what Greek art means, to the end of your days.

204. In this aspect of it, then, I say it is the simplest and nakedest of lovely veracities. But it has another aspect, or rather another pole, for the opposition is diametric. As the simplest, so also it is the most complex of human art. I told you in my Fifth Lecture, showing you the spotty picture of Velasquez, that an essential Greek character is a liking for things that are dappled. And you cannot but have noticed how often and how prevalently the idea which gave its name to the Porch of Polygnotus, "στοα ποικιλη," occurs to the Greeks as connected with the finest art. Thus, when the luxurious city is opposed to the simple and healthful one, in the second book of Plato's Polity, you find that, next to perfumes, pretty ladies, and dice, you must have in it "ποικιλια," which observe, both in that place and again in the third book, is the separate art of joiners' work, or inlaying; but the idea of exquisitely divided variegation or division, both in sight and sound—the "ravishing division to the lute," as in Pindar's "ποικιλοι ὑμνοι"—runs through the compass of all Greek art-description; and if, instead of studying that art among marbles, you were to look at it only on vases of a fine time, (look back, for instance, to Plate IV. here,) your impression of it would be, instead of breadth and simplicity, one of universal spottiness and checkeredness, "εν αγγεωυ Ἑρκεσιν παμποικιλοις;" and of the artist's delighting in nothing so much as in crossed or starred or spotted things; which, in right places, he and his public both do unlimitedly. Indeed they hold it complimentary even to a trout, to call him a 'spotty.' Do you recollect the trout in the tributaries of the Ladon, which Pausanias says were spotted, so that they were like thrushes, and which, the Arcadians told him, could speak? In this last ποικιλια, however, they disappointed him. "I, indeed, saw some of them caught," he says, "but I did not hear any of them speak, though I waited beside the river till sunset."

205. I must sum roughly now, for I have detained you too long.

The Greeks have been thus the origin, not only of all broad, mighty, and calm conception, but of all that is divided, delicate, and tremulous; "variable as the shade, by the light quivering aspen made." To them, as first leaders of ornamental design, belongs, of right, the praise of glistenings in gold, piercings in ivory, stainings in purple, burnishings in dark blue steel; of the fantasy of the Arabian roof,—quartering of the Christian shield,—rubric and arabesque of Christian scripture; in fine, all enlargement, and all diminution of adorning thought, from the temple to the toy, and from the mountainous pillars of Agrigentum to the last fineness of fretwork in the Pisan Chapel of the Thorn.

XXI.

THE BEGINNINGS OF CHIVALRY.

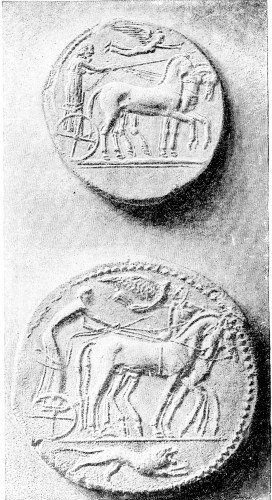

And in their doing all this, they stand as masters of human order and justice, subduing the animal nature, guided by the spiritual one, as you see the Sicilian Charioteer stands, holding his horse-reins, with the wild lion racing beneath him, and the flying angel above, on the beautiful coin of early Syracuse; (lowest in Plate XXI.)

And the beginnings of Christian chivalry were in that Greek bridling of the dark and the white horses.

206. Not that a Greek never made mistakes. He made as many as we do ourselves, nearly;—he died of his mistakes at last—as we shall die of them; but so far as he was separated from the herd of more mistaken and more wretched nations—so far as he was Greek—it was by his rightness. He lived, and worked, and was satisfied with the fatness of his land, and the fame of his deeds, by his justice, and reason, and modesty. He became Græculus esuriens, little, and hungry, and every man's errand-boy, by his iniquity, and his competition, and his love of talk. But his Græcism was in having done, at least at one period of his dominion, more than anybody else, what was modest, useful, and eternally true; and as a workman, he verily did, or first suggested the doing of, everything possible to man.

Take Dædalus, his great type of the practically executive craftsman, and the inventor of expedients in craftsmanship, (as distinguished from Prometheus, the institutor of moral order in art). Dædalus invents,—he, or his nephew,

The potter's wheel, and all work in clay;The saw, and all work in wood;The masts and sails of ships, and all modes of motion;(wings only proving too dangerous!)The entire art of minute ornament;And the deceptive life of statues.By his personal toil, he involves the fatal labyrinth for Minos; builds an impregnable fortress for the Agrigentines; adorns healing baths among the wild parsley-fields of Selinus; buttresses the precipices of Eryx, under the temple of Aphrodite; and for her temple itself—finishes in exquisiteness the golden honeycomb.

207. Take note of that last piece of his art: it is connected with many things which I must bring before you when we enter on the study of architecture. That study we shall begin at the foot of the Baptistery of Florence, which, of all buildings known to me, unites the most perfect symmetry with the quaintest ποικιλια. Then, from the tomb of your own Edward the Confessor, to the farthest shrine of the opposite Arabian and Indian world, I must show you how the glittering and iridescent dominion of Dædalus prevails; and his ingenuity in division, interposition, and labyrinthine sequence, more widely still. Only this last summer I found the dark red masses of the rough sandstone of Furness Abbey had been fitted by him, with no less pleasure than he had in carving them, into wedged hexagons—reminiscences of the honeycomb of Venus Erycina. His ingenuity plays around the framework of all the noblest things; and yet the brightness of it has a lurid shadow. The spot of the fawn, of the bird, and the moth, may be harmless. But Dædalus reigns no less over the spot of the leopard and snake. That cruel and venomous power of his art is marked, in the legends of him, by his invention of the saw from the serpent's tooth; and his seeking refuge, under blood-guiltiness, with Minos, who can judge evil, and measure, or remit, the penalty of it, but not reward good; Rhadamanthus only can measure that; but Minos is essentially the recognizer of evil deeds "conoscitor delle peccata," whom, therefore, you find in Dante under the form of the ερπετον. "Cignesi con la coda tante volte, quantunque gradi vuol che giu sia messa."

And this peril of the influence of Dædalus is twofold; first, in leading us to delight in glitterings and semblances of things, more than in their form, or truth;—admire the harlequin's jacket more than the hero's strength; and love the gilding of the missal more than its words;—but farther, and worse, the ingenuity of Dædalus may even become bestial, an instinct for mechanical labor only, strangely involved with a feverish and ghastly cruelty:—(you will find this distinct in the intensely Dædal work of the Japanese); rebellious, finally, against the laws of nature and honor, and building labyrinths for monsters,—not combs for bees.

208. Gentlemen, we of the rough northern race may never, perhaps, be able to learn from the Greek his reverence for beauty; but we may at least learn his disdain of mechanism:—of all work which he felt to be monstrous and inhuman in its imprudent dexterities.

We hold ourselves, we English, to be good workmen. I do not think I speak with light reference to recent calamity, (for I myself lost a young relation, full of hope and good purpose, in the foundered ship London,) when I say that either an Æginetan or Ionian shipwright built ships that could be fought from, though they were under water; and neither of them would have been proud of having built one that would fill and sink helplessly if the sea washed over her deck, or turn upside-down if a squall struck her topsail.

Believe me, gentlemen, good workmanship consists in continence and common sense, more than in frantic expatiation of mechanical ingenuity; and if you would be continent and rational, you had better learn more of Art than you do now, and less of Engineering. What is taking place at this very hour,40 among the streets, once so bright, and avenues, once so pleasant, of the fairest city in Europe, may surely lead us all to feel that the skill of Dædalus, set to build impregnable fortresses, is not so wisely applied as in framing the τρητον πονον,—the golden honeycomb.

LECTURE VII.

THE RELATION BETWEEN MICHAEL ANGELO AND TINTORET. 41

209. In preceding lectures on sculpture I have included references to the art of painting, so far as it proposes to itself the same object as sculpture, (idealization of form); and I have chosen for the subject of our closing inquiry, the works of the two masters who accomplished or implied the unity of these arts. Tintoret entirely conceives his figures as solid statues: sees them in his mind on every side; detaches each from the other by imagined air and light; and foreshortens, interposes, or involves them as if they were pieces of clay in his hand. On the contrary, Michael Angelo conceives his sculpture partly as if it were painted; and using (as I told you formerly) his pen like a chisel, uses also his chisel like a pencil; is sometimes as picturesque as Rembrandt, and sometimes as soft as Correggio.

It is of him chiefly that I shall speak to-day; both because it is part of my duty to the strangers here present to indicate for them some of the points of interest in the drawings forming part of the University collections; but still more, because I must not allow the second year of my professorship to close, without some statement of the mode in which those collections may be useful or dangerous to my pupils. They seem at present little likely to be either; for since I entered on my duties, no student has ever asked me a single question respecting these drawings, or, so far as I could see, taken the slightest interest in them.

210. There are several causes for this which might be obviated—there is one which cannot be. The collection, as exhibited at present, includes a number of copies which mimic in variously injurious ways the characters of Michael Angelo's own work; and the series, except as material for reference, can be of no practical service until these are withdrawn, and placed by themselves. It includes, besides, a number of original drawings which are indeed of value to any laborious student of Michael Angelo's life and temper; but which owe the greater part of this interest to their being executed in times of sickness or indolence, when the master, however strong, was failing in his purpose, and, however diligent, tired of his work. It will be enough to name, as an example of this class, the sheet of studies for the Medici tombs, No. 45, in which the lowest figure is, strictly speaking, neither a study nor a working drawing, but has either been scrawled in the feverish languor of exhaustion, which cannot escape its subject of thought; or, at best, in idly experimental addition of part to part, beginning with the head, and fitting muscle after muscle, and bone after bone, to it, thinking of their place only, not their proportion, till the head is only about one-twentieth part of the height of the body: finally, something between a face and a mask is blotted in the upper left-hand corner of the paper, indicative, in the weakness and frightfulness of it, simply of mental disorder from over-work; and there are several others of this kind, among even the better drawings of the collection, which ought never to be exhibited to the general public.

211. It would be easy, however, to separate these, with the acknowledged copies, from the rest; and, doing the same with the drawings of Raphael, among which a larger number are of true value, to form a connected series of deep interest to artists, in illustration of the incipient and experimental methods of design practiced by each master.

I say, to artists. Incipient methods of design are not, and ought not to be, subjects of earnest inquiry to other people; and although the re-arrangement of the drawings would materially increase the chance of their gaining due attention, there is a final and fatal reason for the want of interest in them displayed by the younger students;—namely, that these designs have nothing whatever to do with present life, with its passions, or with its religion. What their historic value is, and relation to the life of the past, I will endeavor, so far as time admits, to explain to-day.

212. The course of Art divides itself hitherto, among all nations of the world that have practiced it successfully, into three great periods.

The first, that in which their conscience is undeveloped, and their condition of life in many respects savage; but, nevertheless, in harmony with whatever conscience they possess. The most powerful tribes, in this stage of their intellect, usually live by rapine, and under the influence of vivid, but contracted, religious imagination. The early predatory activity of the Normans, and the confused minglings of religious subjects with scenes of hunting, war, and vile grotesque, in their first art, will sufficiently exemplify this state of a people; having, observe, their conscience undeveloped, but keeping their conduct in satisfied harmony with it.

The second stage is that of the formation of conscience by the discovery of the true laws of social order and personal virtue, coupled with sincere effort to live by such laws as they are discovered.

All the Arts advance steadily during this stage of national growth, and are lovely, even in their deficiencies, as the buds of flowers are lovely by their vital force, swift change, and continent beauty.

213. The third stage is that in which the conscience is entirely formed, and the nation, finding it painful to live in obedience to the precepts it has discovered, looks about to discover, also, a compromise for obedience to them. In this condition of mind its first endeavor is nearly always to make its religion pompous, and please the gods by giving them gifts and entertainments, in which it may piously and pleasurably share itself; so that a magnificent display of the powers of art it has gained by sincerity, takes place for a few years, and is then followed by their extinction, rapid and complete exactly in the degree in which the nation resigns itself to hypocrisy.

The works of Raphael, Michael Angelo, and Tintoret belong to this period of compromise in the career of the greatest nation of the world; and are the most splendid efforts yet made by human creatures to maintain the dignity of states with beautiful colors, and defend the doctrines of theology with anatomical designs.

Farther, and as an universal principle, we have to remember that the Arts express not only the moral temper, but the scholarship, of their age; and we have thus to study them under the influence, at the same moment of, it may be, declining probity, and advancing science.

214. Now in this the Arts of Northern and Southern Europe stand exactly opposed. The Northern temper never accepts the Catholic faith with force such as it reached in Italy. Our sincerest thirteenth-century sculptor is cold and formal compared with that of the Pisani; nor can any Northern poet be set for an instant beside Dante, as an exponent of Catholic faith: on the contrary, the Northern temper accepts the scholarship of the Reformation with absolute sincerity, while the Italians seek refuge from it in the partly scientific and completely lascivious enthusiasms of literature and painting, renewed under classical influence. We therefore, in the north, produce our Shakspeare and Holbein; they their Petrarch and Raphael. And it is nearly impossible for you to study Shakspeare or Holbein too much, or Petrarch and Raphael too little.

I do not say this, observe, in opposition to the Catholic faith, or to any other faith, but only to the attempts to support whatsoever the faith may be, by ornament or eloquence, instead of action. Every man who honestly accepts, and acts upon, the knowledge granted to him by the circumstances of his time, has the faith which God intends him to have;—assuredly a good one, whatever the terms or form of it—every man who dishonestly refuses, or interestedly disobeys the knowledge open to him, holds a faith which God does not mean him to hold, and therefore a bad one, however beautiful or traditionally respectable.

215. Do not, therefore, I entreat you, think that I speak with any purpose of defending one system of theology against another; least of all, reformed against Catholic theology. There probably never was a system of religion so destructive to the loveliest arts and the loveliest virtues of men, as the modern Protestantism, which consists in an assured belief in the Divine forgiveness of all your sins, and the Divine correctness of all your opinions. But in the first searching and sincere activities, the doctrines of the Reformation produced the most instructive art, and the grandest literature, yet given to the world; while Italy, in her interested resistance to those doctrines, polluted and exhausted the arts she already possessed. Her iridescence of dying statesmanship—her magnificence of hollow piety,—were represented in the arts of Venice and Florence by two mighty men on either side—Titian and Tintoret,—Michael Angelo and Raphael. Of the calm and brave statesmanship, the modest and faithful religion, which had been her strength, I am content to name one chief representative artist at Venice, John Bellini.

216. Let me now map out for you roughly the chronological relations of these five men. It is impossible to remember the minor years, in dates; I will give you them broadly in decades, and you can add what finesse afterwards you like.

Recollect, first, the great year 1480. Twice four's eight—you can't mistake it. In that year Michael Angelo was five years old; Titian, three years old; Raphael, within three years of being born.

So see how easily it comes. Michael Angelo five years old—and you divide six between Titian and Raphael,—three on each side of your standard year, 1480.

Then add to 1480, forty years—an easy number to recollect, surely; and you get the exact year of Raphael's death, 1520.

In that forty years all the new effort and deadly catastrophe took place. 1480 to 1520.

Now, you have only to fasten to those forty years, the life of Bellini, who represents the best art before them, and of Tintoret, who represents the best art after them.

217. I cannot fit you these on with a quite comfortable exactness, but with very slight inexactness I can fit them firmly.

John Bellini was ninety years old when he died. He lived fifty years before the great forty of change, and he saw the forty, and died. Then Tintoret is born; lives eighty42 years after the forty, and closes, in dying, the sixteenth century, and the great arts of the world.

Those are the dates, roughly; now for the facts connected with them.

John Bellini precedes the change, meets, and resists it victoriously to his death. Nothing of flaw or failure is ever to be discerned in him.

Then Raphael, Michael Angelo, and Titian, together, bring about the deadly change, playing into each other's hands—Michael Angelo being the chief captain in evil; Titian, in natural force.

Then Tintoret, himself alone nearly as strong as all the three, stands up for a last fight; for Venice, and the old time. He all but wins it at first; but the three together are too strong for him. Michael Angelo strikes him down; and the arts are ended. "Il disegno di Michael Agnolo." That fatal motto was his death-warrant.

218. And now, having massed out my subject, I can clearly sketch for you the changes that took place from Bellini, through Michael Angelo, to Tintoret.

The art of Bellini is centrally represented by two pictures at Venice: one, the Madonna in the Sacristy of the Frari, with two saints beside her, and two angels at her feet; the second, the Madonna with four Saints, over the second altar of San Zaccaria.