полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 1

24. The cultivating status that of the Vaishya

The suggested conclusion from the above argument is that the main body of the Aryan immigrants, that is the Vaishyas, settled down in villages by exogamous clans or septs. The cultivators of each village believed themselves to be kinsmen descended from a common ancestor, and also to be akin to the god of the village lands from which they drew their sustenance. Hence their order had an equal right to cultivate the village land and their children to inherit it, though they did not conceive of the idea of ownership of land in the sense in which we understand this phrase.

The original status of the Vaishya, or a full member of the Aryan community who could join in sacrifices and employ Brāhmans to perform them, was gradually transferred to the cultivating member of the village communities. In process of time, as land was the chief source of wealth, and was also regarded as sacred, the old status became attached to castes or groups of persons who obtained or held land irrespective of their origin, and these are what are now called the good cultivating castes. They have now practically the same status, though, as has been seen, they were originally of most diverse origin, including bands of robbers and freebooters, cattle-lifters, non-Aryan tribes, and sections of any castes which managed to get possession of an appreciable quantity of land.

25. Higher professional and artisan castes

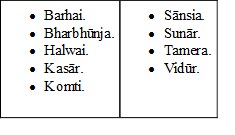

The second division of the group of pure or good castes, or those from whom a Brāhman can take water, comprises the higher artisan castes:

The most important of these are the Sunār or goldsmith; the Kasār or worker in brass and bell-metal; the Tamera or coppersmith; the Barhai or carpenter; and the Halwai and Bharbhūnja or confectioner and grain-parcher. The Sānsia or stone-mason of the Uriya country may perhaps also be included. These industries represent a higher degree of civilisation than the village trades, and the workers may probably have been formed into castes at a later period, when the practice of the handicrafts was no longer despised. The metal-working castes are now usually urban, and on the average their members are as well-to-do as the cultivators. The Sunārs especially include a number of wealthy men, and their importance is increased by their association with the sacred metal, gold; in some localities they now claim to be Brāhmans and refuse to take food from Brāhmans.62 The more ambitious members abjure all flesh-food and liquor and wear the sacred thread. But in Bombay the Sunār was in former times one of the village menial castes, and here, before and during the time of the Peshwas, Sunārs were not allowed to wear the sacred thread, and they were forbidden to hold their marriages in public, as it was considered unlucky to see a Sunār bridegroom. Sunār bridegrooms were not allowed to see the state umbrella or to ride in a palanquin, and had to be married at night and in secluded places, being subject to restrictions and annoyances from which even Mahārs were free. Thus the goldsmith’s status appears to vary greatly according as his trade is a village or urban industry. Copper is also a sacred metal, and the Tameras rank next to the Sunārs among the artisan castes, with the Kasārs or brass-workers a little below them; both these castes sometimes wearing the sacred thread. These classes of artisans generally live in towns. The Barhai or carpenter is sometimes a village menial, but most carpenters live in towns, the wooden implements of agriculture being made either by the blacksmith or by the cultivators themselves. Where the Barhai is a village menial he is practically on an equality with the Lohār or blacksmith; but the better-class carpenters, who generally live in towns, rank higher. The Sānsia or stone-mason of the Uriya country works, as a rule, only in stone, and in past times therefore his principal employment must have been to build temples. He could not thus be a village menial, and his status would be somewhat improved by the sanctity of his calling. The Halwai and Bharbhūnja or confectioner and grain-parcher are castes of comparatively low origin, especially the latter; but they have to be given the status of ceremonial purity in order that all Hindus may be able to take sweets and parched grain from their hands. Their position resembles that of the barber and waterman, the pure village menials, which will be discussed later. In Bengal certain castes, such as the Tānti or weaver of fine muslin, the Teli or oil-presser, and the Kumhār or potter, rank with the ceremonially pure castes. Their callings have there become important urban industries. Thus the Tāntis made the world-renowned fine muslins of Dacca; and the Jagannāthia Kumhārs of Orissa provide the earthen vessels used for the distribution of rice to all pilgrims at the temple of Jagannāth. These castes and certain others have a much higher rank than that of the corresponding castes in northern and Central India, and the special reasons indicated seem to account for this. Generally the artisan castes ranking on the same or a higher level than the cultivators are urban and not rural. They were not placed in a position of inferiority to the cultivators by accepting contributions of grain and gifts from them, and this perhaps accounts for their higher position. One special caste may be noticed here, the Vidūrs, who are the descendants of Brāhman fathers by women of other castes. These, being of mixed origin, formerly had a very low rank, and worked as village accountants and patwāris. Owing to their connection with Brāhmans, however, they are a well-educated caste, and since education has become the door to all grades of advancement in the public service, the Vidūrs have taken advantage of it, and many of them are clerks of offices or hold higher posts under Government. Their social status has correspondingly improved; they dress and behave like Brāhmans, and in some localities it is said that even Marātha Brāhmans will take water to drink from Vidūrs, though they will not take it from the cultivating castes. There are also several menial or serving castes from whom a Brāhman can take water, forming the third class of this group, but their real rank is much below that of the cultivators, and they will be treated in the next group.

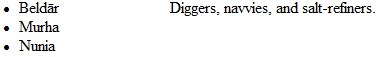

26. Castes from whom a Brāhman cannot take water; the village menials

The third main division consists of those castes from whom a Brāhman cannot take water, though they are not regarded as impure and are permitted to enter Hindu temples. The typical castes of this group appear to be the village artisans and menials and the village priests. The annexed list shows the principal of these.

Village menials.

• Lohār—Blacksmith.

• Barhai—Carpenter.

• Kumhār—Potter.

• Nai—Barber.

• Dhimar—Waterman.

• Kahār—Palanquin-bearer.

• Bāri—Leaf-plate maker.

• Bargāh—Household servant.

• Dhobi—Washerman.

• Darzi—Tailor.

• Basor or Dhulia—Village musician.

• Bhāt and Mirāsi—Bard and genealogist.

• Halba—House-servant and farm-servant.

Castes of village watchmen.

• Khangār.

• Chadār.

• Chauhān.

• Dahāit.

• Panka.

Village priests and mendicants.

• Joshi—Astrologer.

• Gārpagāri—Hail-averter.

• Gondhali—Musician.

Others.

• Māli—Gardener and maker of garlands.

• Barai—Betel-vine grower and seller.

Other village traders and artisans.

• Kalār—Liquor-vendor.

• Teli—Oil-presser.

Banjāra—Carrier.

• Bahna—Cotton-cleaner.

• Chhīpa—Calico-printer and dyer.

• Chitrakathi—Painter and picture-maker.

• Kachera—Glass bangle-maker.

• Kadera—Fireworks-maker.

• Nat—Acrobat.

The essential fact which formerly governed the status of this group of castes appears to be that they performed various services for the cultivators according to their different vocations, and were supported by contributions of grain made to them by the cultivators, and by presents given to them at seed-time and harvest. They were the clients of the cultivators and the latter were their patrons and supporters, and hence ranked above them. This condition of things survives only in the case of a few castes, but prior to the introduction of a metal currency must apparently have been the method of remuneration of all the village industries. The Lohār or blacksmith makes and mends the iron implements of agriculture, such as the ploughshare, axe, sickle and goad. For this he is paid in Saugor a yearly contribution of 20 lbs. of grain per plough of land held by each cultivator, together with a handful of grain at sowing-time and a sheaf at harvest from both the autumn and spring crops. In Wardha he gets 50 lbs. of grain per plough of four bullocks or 40 acres. For new implements he must either be paid separately or at least supplied with the iron and charcoal. In Districts where the Barhai or carpenter is a village servant he is paid the same as the Lohār and has practically an equal status. The village barber receives in Saugor 20 lbs. of grain annually from each adult male in the family, or 22½ lbs. per plough of land besides the seasonal presents. In return for this he shaves each cultivator over the head and face about once a fortnight. The Dhobi or washerman gets half the annual contribution of the blacksmith and carpenter, with the same presents, and in return for this he washes the clothes of the family two or three times a month. When he brings the clothes home he also receives a meal or a wheaten cake, and well-to-do families give him their old clothes as a present. The Dhīmar or waterman brings water to the house morning and evening, and fills the earthen water-pots placed on a wooden stand or earthen platform outside it. When the cultivators have marriages he performs the same duties for the whole wedding party, and receives a present of money and clothes according to the means of the family, and his food every day while the wedding is in progress. He supplies water for drinking to the reapers, receiving three sheaves a day as payment, and takes sweet potatoes and boiled plums to the field and sells them. The Kumhār or potter is not now paid regularly by dues from the cultivators like other village menials, as the ordinary system of sale has been found to be more convenient in his case. But he sometimes takes for use the soiled grass from the stalls of the cattle and gives pots free to the cultivator in exchange. On Akti day, at the beginning of the agricultural year, the village Kumhār in Saugor presents five pots with covers on them to each cultivator and is given 2½ lbs. of grain. He presents the bride with seven new pots at a wedding, and these are filled with water and used in the ceremony, being considered to represent the seven seas. At a funeral he must supply thirteen vessels which are known as ghāts, and must replace the household earthen vessels, which are rendered impure on the occurrence of a death in the house, and are all broken and thrown away. In the Punjab and Marātha country the Kumhār was formerly an ordinary village menial.

27. The village watchmen

The office of village watchman is an important one, and is usually held by a member of the indigenous tribes. These formerly were the chief criminals, and the village watchman, in return for his pay, was expected to detect the crimes of his tribesmen and to make good any losses of property caused by them. The sections of the tribes who held this office have developed into special castes, as the Khangārs, Chadārs and Chauhāns of Chhattīsgarh. These last are probably of mixed descent from Rājpūts and the higher castes of cultivators with the indigenous tribes. The Dahāits were a caste of gatekeepers and orderlies of native rulers who have now become village watchmen. The Pankas are a section of the impure Gānda caste who have embraced the doctrines of the Kabīrpanthi sect and formed a separate caste. They are now usually employed as village watchmen and are not regarded as impure. Similarly those members of the Mahār servile caste who are village watchmen tend to marry among themselves and form a superior group to the others. The village watchman now receives a remuneration fixed by Government and is practically a rural policeman, but in former times he was a village menial and was maintained by the cultivators in the same manner as the others.

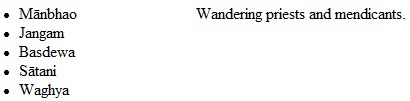

28. The village priests. The gardening castes

The village priests are another class of this group. The regular village priest and astrologer, the Joshi or Parsai, is a Brāhman, but the occupation has developed a separate caste. The Joshi officiates at weddings in the village, selects auspicious names for children according to the constellations under which they were born, and points out the auspicious moment or mahūrat for weddings, name-giving and other ceremonies, and for the commencement of such agricultural operations as sowing, reaping, and threshing. He is also sometimes in charge of the village temple. He is supported by contributions of grain from the villagers and often has a plot of land rent-free from the proprietor. The social position of the Joshis is not very good, and, though Brāhmans, they are considered to rank somewhat below the cultivating castes. The Gurao is another village priest, whose fortune has been quite different. The caste acted as priests of the temples of Siva and were also musicians and supplied leaf-plates. They were village menials of the Marātha villages. But owing to the sanctity of their calling, and the fact that they have become literate and taken service under Government, the Guraos now rank above the cultivators and are called Shaiva Brāhmans. The Gondhalis are the village priests of Devi, the earth-goddess, who is also frequently the tutelary goddess of the village. They play the kettle-drum and perform dances in her honour, and were formerly classed as one of the village menials of Marātha villages, though they now work for hire. The Gārpagāri, or hail-averter, is a regular village menial, his duty being to avert hail-storms from the crops, like the χαλαζοφύλαξ in ancient Greece. The Gārpagāris will accept cooked food from Kunbis and celebrate their weddings with those of the Kunbis. The Jogis, Mānbhaos, Sātanis, and others, are wandering religious mendicants, who act as priests and spiritual preceptors to the lower classes of Hindus.

Group of religious mendicants

With the village priests may be mentioned the Māli or gardener. The Mālis now grow vegetables with irrigation or ordinary crops, but this was not apparently their original vocation. The name is derived from māla, a garland, and it would appear that the Māli was first employed to grow flowers for the garlands with which the gods and also their worshippers were adorned at religious ceremonies. Flowers were held sacred and were an essential adjunct to worship in India as in Greece and Rome. The sacred flowers of India are the lotus, the marigold and the champak63 and from their use in religious worship is derived the custom of adorning the guests with garlands at all social functions, just as in Rome and Greece they wore crowns on their heads. It seems not unlikely that this was the purpose for which cultivated flowers were first grown, at any rate in India. The Māli was thus a kind of assistant in the religious life of the village, and he is still sometimes placed in charge of the village shrines and is employed as temple-servant in Jain temples. He would therefore have been supported by contributions from the cultivators like the other village menials and have ranked below them, though on account of the purity and sanctity of his occupation Brāhmans would take water from him. The Māli has now become an ordinary cultivator, but his status is still noticeably below that of the good cultivating castes and this seems to be the explanation. With the Māli may be classed the Barai, the grower and seller of the pān or betel-vine leaf. This leaf, growing on a kind of creeper, like the vine, in irrigated gardens roofed with thatch for protection from the sun, is very highly prized by the Hindus. It is offered with areca-nut, cloves, cardamom and lime rolled up in a quid to the guests at all social functions. It is endowed by them with great virtues, being supposed to prevent heartburn, indigestion, and other stomachic and intestinal disorders, and to preserve the teeth, while taken with musk, saffron and almonds, the betel-leaf is held to be a strong aphrodisiac. The juice of the leaf stains the teeth and mouth red, and the effect, though repulsive to Europeans, is an indispensable adjunct to a woman’s beauty in Hindu eyes. This staining of the mouth red with betel-leaf is also said to distinguish a man from a dog. The idea that betel preserves the teeth seems to be unfounded. The teeth of Hindus appear to be far less liable to decay than those of Europeans, but this is thought to be because they generally restrict themselves to a vegetable diet and always rinse out their mouths with water after taking food. The betel-leaf is considered sacred; a silver ornament is made in its shape and it is often invoked in spells and magic. The original vine is held to have grown from a finger-joint of Bāsuki, the Queen of the Serpents, and the cobra is worshipped as the tutelary deity of the pān-garden, which this snake is accustomed to frequent, attracted by the moist coolness and darkness. The position of the Barai is the same as that of the Māli; his is really a low caste, sometimes coupled with the contemned Telis or oil-pressers, but he is considered ceremonially pure because the betel-leaf, offered to gods and eaten by Brāhmans and all Hindus, is taken from him. The Barai or Tamboli was formerly a village menial in the Marātha villages.

29. Other village traders and menials

The castes following other village trades mainly fall into this group, though they may not now be village menials. Such are the Kalār or liquor-vendor and Teli or oil-presser, who sell their goods for cash, and having learnt to reckon and keep accounts, have prospered in their dealings with the cultivators ignorant of this accomplishment. Formerly it is probable that the village Teli had the right of pressing all the oil grown in the village, and retaining a certain share for his remuneration. The liquor-vendor can scarcely have been a village menial, but since Manu’s time his trade has been regarded as a very impure one, and has ranked with that of the Teli. Both these castes have now become prosperous, and include a number of landowners, and their status is gradually improving. The Darzi or tailor is not usually attached to the village community; sewn clothes have hitherto scarcely been worn among the rural population, and the weaver provides the cloths which they drape on the body and round the head.64 The contempt with which the tailor is visited in English proverbial lore for working at a woman’s occupation attaches in a precisely similar manner in India to the weaver.65 But in Gujarāt the Darzi is found living in villages and here he is also a village menial. The Kachera or maker of the glass bangles which every Hindu married woman wears as a sign of her estate, ranks with the village artisans; his is probably an urban trade, but he has never become prosperous or important. The Banjāras or grain-carriers were originally Rājpūts, but owing to the mixed character of the caste and the fact that they obtained their support from the cultivators, they have come to rank below these latter. The Wanjāri cultivators of Berār have now discarded their Banjāra ancestry and claim to be Kunbis. The Nat or rope-dancer and acrobat may formerly have had functions in the village in connection with the crops. In Kumaon66 a Nat still slides down a long rope from the summit of a cliff to the base as a rite for ensuring the success of the crops on the occasion of a festival of Siva. Formerly if the Nat or Bādi fell to the ground in his course, he was immediately despatched with a sword by the surrounding spectators, but this is now prohibited. The rope on which he slid down the cliff is cut up and distributed among the inhabitants of the village, who hang the pieces as charms on the eaves of their houses. The hair of the Nat is also taken and preserved as possessing similar virtues. Each District in Kumaon has its hereditary Nat or Bādi, who is supported by annual contributions of grain from the inhabitants. Similarly in the Central Provinces it is not uncommon to find a deified Nat, called Nat Bāba or Father Nat, as a village god. A Natni, or Nat woman, is sometimes worshipped; and when two sharp peaks of hills are situated close to each other, it is related that there was once a Natni, very skilful on the tight-rope, who performed before the king; and he promised her that if she would stretch a rope from the peak of one hill to that of the other, and walk across it, he would marry her and make her wealthy. Accordingly the rope was stretched, but the queen from jealousy went and cut it nearly through in the night, and when the Natni started to walk, the rope broke, and she fell down and was killed. Having regard to the Kumaon rite, it may be surmised that these legends commemorate the death of a Natni or acrobat during the performance of some feat of dancing or sliding on a rope for the magical benefit of the crops. And it seems possible that acrobatic performances may have had their origin in this manner. The point bearing on the present argument is, however, that the Nat performed special functions for the success of the village crops, and on this account was supported by contributions from the villagers, and ranked with the village menials.

30. Household servants

Some of the castes already mentioned, and one or two others having the same status, work as household servants as well as village menials. The Dhīmar is most commonly employed as an indoor servant in Hindu households, and is permitted to knead flour in water and make it into a cake, which the Brāhman then takes and puts on the girdle with his own hands. He can boil water and pour pulse into the cooking-pot from above, so long as he does not touch the vessel after the food has been placed in it. He will take any remains of food left in the cooking-pot, as this is not considered to be polluted, food only becoming polluted when the hand touches it on the dish after having touched the mouth. When this happens, all the food on the dish becomes jūtha or leavings of food, and as a general rule no caste except the sweepers will eat these leavings of food of another caste or of another person of their own. Only a wife, whose meal follows her husband’s, will eat his leavings. As a servant, the Dhīmar is very familiar with his master; he may enter any part of the house, including the cooking-place and the women’s rooms, and he addresses his mistress as ‘Mother.’ When he lights his master’s pipe he takes the first pull himself, to show that it has not been tampered with, and then presents it to him with his left hand placed under his right elbow in token of respect. Maid-servants frequently belong also to the Dhīmar caste, and it often happens that the master of the household has illicit intercourse with them. Hence there is a proverb: ‘The king’s son draws water and the water-bearer’s son sits on the throne,’—similar intrigues on the part of high-born women with their servants being not unknown. The Kahār or palanquin-bearer was probably the same caste as the Dhīmar. Landowners would maintain a gang of Kahārs to carry them on journeys, allotting to such men plots of land rent-free. Our use of the word ‘bearer’ in the sense of a body-servant has developed from the palanquin-bearer who became a personal attendant on his master. Well-to-do families often have a Nai or barber as a hereditary family servant, the office descending in the barber’s family. Such a man arranges the marriages of the children and takes a considerable part in conducting them, and acts as escort to the women of the family when they go on a journey. Among his daily duties are to rub his master’s body with oil, massage his limbs, prepare his bed, tell him stories to send him to sleep, and so on. The barber’s wife attends on women in childbirth after the days of pollution are over, and rubs oil on the bodies of her clients, pares their nails and paints their feet with red dye at marriages and on other festival occasions. The Bāri or maker of leaf-plates is another household servant. Plates made of large leaves fastened together with little wooden pins and strips of fibre are commonly used by the Hindus for eating food, as are little leaf-cups for drinking; glazed earthenware has hitherto not been commonly manufactured, and that with a rougher surface becomes ceremonially impure by contact with any strange person or thing. Metal vessels and plates are the only alternative to those made of leaves, and there are frequently not enough of them to go round for a party. The Bāris also work as personal servants, hand round water, and light and carry torches at entertainments and on journeys. Their women are maids to high-caste Hindu ladies, and as they are always about the zenana are liable to lose their virtue.