полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 1

Formerly an annual fair was held at Bhandār to which all the Satnāmis went and drank the water in which the guru had dipped his big toe. Each man gave him not less than a rupee and sometimes as much as fifty rupees. But the fair is no longer held and now the Satnāmis only give the guru a cocoanut when he goes on tour. The Satnāmis also have a fair in Ratanpur, a sacred place of the Hindus, where they assemble and bathe in a tank of their own, as they are not allowed to bathe in the Hindu tanks.

5. Social profligacy

Formerly, when a Satnāmi Chamār was married, a ceremony called Satlok took place within three years of the wedding, or after the birth of the first son, which Mr. Durga Prasād Pānde describes as follows: it was considered to be the initiatory rite of a Satnāmi, so that prior to its performance he and his wife were not proper members of the sect. When the occasion was considered ripe, a committee of men in the village would propose the holding of the ceremony to the bridegroom; the elderly members of his family would also exert their influence upon him, because it was believed that if they died prior to its performance their disembodied spirits would continue a comfortless existence about the scene of their mortal habitation, but if afterwards that they would go straight to heaven. When the rite was to be held a feast was given, the villagers sitting round a lighted lamp placed on a water-pot in the centre of the sacred chauk or square made with lines of wheat-flour; and from evening until midnight they would sing and dance. In the meantime the newly married wife would be lying alone in a room in the house. At midnight her husband went in to her and asked her whom he should revere as his guru or preceptor. She named a man and the husband went out and bowed to him and he then went in to the woman and lay with her. The process would be repeated, the woman naming different men until she was exhausted. Sometimes, if the head priest of the sect was present, he would nominate the favoured men, who were known as gurus. Next morning the married couple were seated together in the courtyard, and the head priest or his representative tied a kanthi or necklace of wooden beads round their necks, repeating an initiatory text.389 This silly doggerel, as shown in the footnote, is a good criterion of the intellectual capacity of the Satnāmis. It is also said that during his annual progresses it was the custom for the chief priest to be allowed access to any of the wives of the Satnāmis whom he might select, and that this was considered rather an honour than otherwise by the husband. But the Satnāmis have now become ashamed of such practices, and, except in a few isolated localities, they have been abandoned.

6. Divisions of the Satnāmis

Ghāsi Dās or his disciples seem to have felt the want of a more ancient and dignified origin for the sect than one dating only from living memory. They therefore say that it is a branch of that founded by Rohi Dās, a Chamār disciple of the great liberal and Vaishnavite reformer Rāmānand, who flourished at the end of the fourteenth century. The Satnāmis commonly call themselves Rohidāsi as a synonym for their name, but there is no evidence that Rohi Dās ever came to Chhattīsgarh, and there is practically no doubt, as already pointed out, that Ghāsi Dās simply appropriated the doctrine of the Satnāmi sect of northern India. One of the precepts of Ghāsi Dās was the prohibition of the use of tobacco, and this has led to a split in the sect, as many of his disciples found the rule too hard for them. They returned to their chongis or leaf-pipes, and are hence called Chungias; they say that in his later years Ghāsi Dās withdrew the prohibition. The Chungias have also taken to idolatry, and their villages contain stones covered with vermilion, the representations of the village deities, which the true Satnāmis eschew. They are considered lower than the Satnāmis, and intermarriage between the two sections is largely, though not entirely, prohibited. A Chungia can always become a Satnāmi if he ceases to smoke by breaking a cocoanut in the presence of his guru or preceptor or giving him a present. Among the Satnāmis there is also a particularly select class who follow the straitest sect of the creed and are called Jaharia from jahar, an essence. These never sleep on a bed but always on the ground, and are said to wear coarse uncoloured clothes and to eat no food but pulse or rice.

7. Customs of the Satnāmis

The social customs of the Satnāmis resemble generally those of other Chamārs. They will admit into the community all except members of “the impure castes, as Dhobis (washermen), Ghasias (grass-cutters) and Mehtars (sweepers), whom they regard as inferior to themselves. Their weddings must be celebrated only during the months of Māgh (January), Phāgun (February), the light half of Chait (March) and Baisākh (April). No betrothal ceremony can take place during the months of Shrāwan (August) and Pūs (January). They always bury the dead, laying the body with the face downwards, and spread clothes in the grave above and below it, so that it may be warm and comfortable during the last long sleep. They observe mourning for three days and have their heads shaved on the third day with the exception of the upper lip, which is never touched by the razor. The Satnāmis as well as the Kabīrpanthis in Chhattīsgarh abstain from spirituous liquor, and ordinary Hindus who do not do so are known as Saktaha or Sakta (a follower of Devi) in contradistinction to them. A Satnāmi is put out of caste if he is beaten by a man of another caste, however high, and if he is touched by a sweeper, Ghasia or Mahār. Their women wear nose-rings, simply to show their contempt for the Hindu social order, as this ornament was formerly forbidden to the lower castes. Under native dynasties any violation of a rule of this kind would have been severely punished by the executive Government, but in British India the Chamār women can indulge their whim with impunity. It was also a rule of the sect not to accept cooked food from the hands of any other caste, whether Hindu or Muhammadan, but this has fallen into abeyance since the famines. Another method by which the Satnāmis show their contempt for the Hindu religion is by throwing milk and curds at each other in sport and trampling it under foot. This is a parody of the Hindu celebration of the Janam-Ashtami or Krishna’s birthday, when vessels of milk and curds are broken over the heads of the worshippers and caught and eaten by all castes indiscriminately in token of amity. They will get into railway carriages and push up purposely against the Hindus, saying that they have paid for their tickets and have an equal right to a place. Then the Hindus are defiled and have to bathe in order to become clean.

8. Character of the Satnāmi movement

Several points in the above description point to the conclusion that the Satnāmi movement is in essence a social revolt on the part of the despised Chamārs or tanners. The fundamental tenet of the gospel of Ghāsi Dās, as in the case of so many other dissenting sects, appears to have been the abolition of caste, and with it of the authority of the Brāhmans; and this it was which provoked the bitter hostility of the priestly order. It has been seen that Ghāsi Dās himself had been deeply impressed by the misery and debasement of the Chamār community; how his successor Bālak Dās was murdered for the assumption of the sacred thread; and how in other ways the Satnāmis try to show their contempt for the social order which brands them as helot outcastes. A large proportion of the Satnāmi Chamārs are owners or tenants of land, and this fact may be surmised to have intensified their feeling of revolt against the degraded position to which they were relegated by the Hindus. Though slovenly cultivators and with little energy or forethought, the Chamārs have the utmost fondness for land and an ardent ambition to obtain a holding, however small. The possession of land is a hall-mark of respectability in India, as elsewhere, and the low castes were formerly incapable of holding it; and it may be surmised that the Chamār feels himself to be raised by his tenant-right above the hereditary condition of village drudge and menial. But for the restraining influence of the British power, the Satnāmi movement might by now have developed in Chhattīsgarh into a social war. Over most of India the term Hindu is contrasted with Muhammadan, but in Chhattīsgarh to call a man a Hindu conveys primarily that he is not a Chamār, or Chamara according to the contemptuous abbreviation in common use. A bitter and permanent antagonism exists between the two classes, and this the Chamār cultivators carry into their relations with their Hindu landlords by refusing to pay rent. The records of the criminal courts contain many cases arising from collisions between Chamārs and Hindus, several of which have resulted in riot and murder. Faults no doubt exist on both sides, and Mr. Hemingway, Settlement Officer, quotes an instance of a Hindu proprietor who made his Chamār tenants cart timber and bricks to Rājim, many miles from his village, to build a house for him during the season of cultivation, their fields consequently remaining untilled. But if a proprietor once arouses the hostility of his Chamār tenants he may as well abandon his village for all the profit he is likely to obtain from it. Generally the Chamārs are to blame, as pointed out by Mr. Blenkinsop who knows them well, and many of them are dangerous criminals, restrained only by their cowardice from the worst outrages against person and property. It may be noted in conclusion that the spread of Christianity among the Chamārs is in one respect a replica of the Satnāmi movement, because by becoming a Christian the Chamār hopes also to throw off the social bondage of Hinduism. A missionary gentleman told the writer that one of the converted Chamārs, on being directed to perform some menial duty of the village, replied: ‘No, I have become a Christian and am one of the Sāhibs; I shall do no more bigār (forced labour).’

Sikh Religion

1. Foundation of Sikhism—Bāba Nānak

Sikh, Akāli.—The Sikh religion and the history of the Sikhs have been fully described by several writers, and all that is intended in this article is a brief outline of the main tenets of the sect for the benefit of those to whom the more important works of reference may not be available. The Central Provinces contained only 2337 Sikhs in 1911, of whom the majority were soldiers and the remainder probably timber or other merchants or members of the subordinate engineering service in which Punjabis are largely employed. The following account is taken from Sir Denzil Ibbetson’s Census Report of the Punjab for 1881:

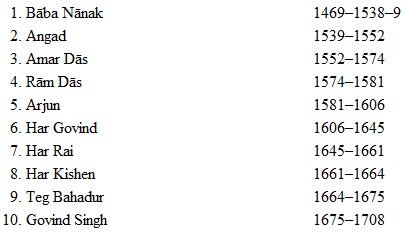

“Sikhism was founded by Bāba Nānak, a Khatri of the Punjab, who lived in the fifteenth century. But Nānak was not more than a religious reformer like Kabīr, Rāmānand, and the other Vaishnava apostles. He preached the unity of God, the abolition of idols, and the disregard of caste distinctions.390 His doctrine and life were eminently gentle and unaggressive. He was succeeded by nine gurus, the last and most famous of whom, Govind Singh, died in 1708.

“The names of the gurus were as follows:

2. The earlier Gurus

“Under the second Guru Angad an intolerant and ascetic spirit began to spring up among the followers of the new tenets; and had it not been for the good sense and firmness displayed by his successor, Amar Dās, who excommunicated the Udāsis and recalled his followers to the mildness and tolerance of Nānak, Sikhism would probably have merely added one more to the countless orders of ascetics or devotees which are wholly unrepresented in the life of the people. The fourth guru, Rām Dās, founded Amritsar; but it was his successor, Arjun, that first organised his following. He gave them a written rule of faith in the Granth or Sikh scripture which he compiled, he provided a common rallying-point in the city of Amritsar which he made their religious centre, and he reduced their voluntary contributions to a systematic levy which accustomed them to discipline and paved the way for further organisation. He was a great trader, he utilised the services and money of his disciples in mercantile transactions which extended far beyond the confines of India, and he thus accumulated wealth for his Church.

“Unfortunately he was unable wholly to abstain from politics; and having become a political partisan of the rebel prince Khusru, he was summoned to Delhi and there imprisoned, and the treatment he received while in confinement hastened, if it did not cause, his death. And thus began that Muhammadan persecution which was so mightily to change the spirit of the new faith. This was the first turning-point in Sikh history; and the effects of the persecution were immediately apparent. Arjun was a priest and a merchant; his successor, Har Govind, was a warrior. He abandoned the gentle and spiritual teaching of Nānak for the use of arms and the love of adventure. He encouraged his followers to eat flesh, as giving them strength and daring; he substituted zeal in the cause for saintliness of life as the price of salvation; and he developed the organised discipline which Arjun had initiated. He was, however, a military adventurer rather than an enthusiastic zealot, and fought either for or against the Muhammadan empire as the hope of immediate gain dictated. His policy was followed by his two successors; and under Teg Bahādur the Sikhs degenerated into little better than a band of plundering marauders, whose internal factions aided to make them disturbers of the public peace. Moreover, Teg Bahādur was a bigot, while the fanatical Aurāngzeb had mounted the throne of Delhi. Him therefore Aurāngzeb captured and executed as an infidel, a robber and a rebel, while he cruelly persecuted his followers in common with all who did not accept Islām.

3. Guru Govind Singh

“Teg Bahādur was succeeded by the last and greatest guru, his son Govind Singh; and it was under him that what had sprung into existence as a quietist sect of a purely religious nature, and had become a military society of by no means high character, developed into the political organisation which was to rule the whole of north-western India, and to furnish the British arms their stoutest and most worthy opponents. For some years after his father’s execution Govind Singh lived in retirement, and brooded over his personal wrongs and over the persecutions of the Musalmān fanatic which bathed the country in blood. His soul was filled with the longing for revenge; but he felt the necessity for a larger following and a stronger organisation, and, following the example of his Muhammadan enemies, he used his religion as the basis of political power. Emerging from his retirement he preached the Khālsa, the pure, the elect, the liberated. He openly attacked all distinctions of caste, and taught the equality of all men who would join him; and instituting a ceremony of initiation, he proclaimed it as the pāhul or ‘gate’ by which all might enter the society, while he gave to its members the prasād or communion as a sacrament of union in which the four castes should eat of one dish. The higher castes murmured and many of them left him, for he taught that the Brāhman’s thread must be broken; but the lower orders rejoiced and flocked in numbers to his standard. These he inspired with military ardour, with the hope of social freedom and of national independence, and with abhorrence of the hated Muhammadan. He gave them outward signs of their faith in the unshorn hair, the short drawers, and the blue dress; he marked the military nature of their calling by the title of Singh or ‘lion,’ by the wearing of steel, and by the initiation by sprinkling of water with a two-edged dagger; and he gave them a feeling of personal superiority in their abstinence from the unclean tobacco.

“The Muhammadans promptly responded to the challenge, for the danger was too serious to be neglected; the Sikh army was dispersed, and Govind’s mother, wife and children were murdered at Sirhind by Aurāngzeb’s orders. The death of the emperor brought a temporary lull, and a year later Govind himself was assassinated while fighting the Marāthas as an ally of Aurāngzeb’s successor. He did not live to see his ends accomplished, but he had roused the dormant spirit of the people, and the fire which he lit was only damped for a while. His chosen disciple Banda succeeded him in the leadership, though never recognised as guru. The internal commotions which followed upon the death of the emperor, Bahādur Shah, and the attacks of the Marāthas weakened the power of Delhi, and for a time Banda carried all before him; but he was eventually conquered and captured in A.D. 1716, and a period of persecution followed so sanguinary and so terrible that for a generation nothing more was heard of the Sikhs. How the troubles of the Delhi empire thickened, how the Sikhs again rose to prominence, how they disputed the possession of the Punjab with the Mughals, the Marāthas and the Durāni, and were at length completely successful, how they divided into societies under their several chiefs and portioned out the Province among them, and how the genius of Ranjīt Singh raised him to supremacy and extended his rule beyond the limits of the Punjab, are matters of political and not of religious history. No formal alteration has been made in the Sikh religion since Govind Singh gave it its military shape; and though changes have taken place, they have been merely the natural result of time and external influences.

4. Sikh initiation and rules

“The word Sikh is said to be derived from the common Hindu term Sewak and to mean simply a disciple; it may be applied therefore to the followers of Nānak who held aloof from Govind Singh, but in practice it is perhaps understood to mean only the latter, while the Nānakpanthis are considered as Hindus. A true Sikh always takes the termination Singh to his name on initiation, and hence they are sometimes known as Singhs in distinction to the Nānakpanthis. A man is also not born a Sikh, but must always be initiated, and the pāhul or rite of baptism cannot take place until he is old enough to understand it, the earliest age being seven, while it is often postponed till manhood. Five Sikhs must be present at the ceremony, when the novice repeats the articles of the faith and drinks sugar and water stirred up with a two-edged dagger. At the initiation of women a one-edged dagger is used, but this is seldom done. Thus most of the wives of Sikhs have never been initiated, nor is it necessary that their children should become Sikhs when they grow up. The faith is unattractive to women owing to the simplicity of its ritual and the absence of the feasts and ceremonies so abundant in Hinduism; formerly the Sikhs were accustomed to capture their wives in forays, and hence perhaps it was considered of no consequence that the husband and wife should be of different faith. The distinguishing marks of a true Sikh are the five Kakkas or K’s which he is bound to carry about his person: the Kes or uncut hair and unshaven beard; the Kachh or short drawers ending above the knee; the Kasa or iron bangle; the Khanda or steel knife; and the Kanga or comb. The other rules of conduct laid down by Guru Govind Singh for his followers were to dress in blue clothes and especially eschew red or saffron-coloured garments and caps of all sorts, to observe personal cleanliness, especially in the hair, and practise ablutions, to eat the flesh of such animals only as had been killed by jatka or decapitation, to abstain from tobacco in all its forms, never to blow out flame nor extinguish it with drinking-water, to eat with the head covered, pray and recite passages of the Granth morning and evening and before all meals, reverence the cow, abstain from the worship of saints and idols and avoid mosques and temples, and worship the one God only, neglecting Brāhmans and Mullas, and their scriptures, teaching, rites and religious symbols. Caste distinctions he positively condemned and instituted the prasād or communion, in which cakes of flour, butter and sugar are made and consecrated with certain ceremonies while the communicants sit round in prayer, and then distributed equally to all the faithful present, to whatever caste they may belong. The above rules, so far as they enjoin ceremonial observances, are still very generally obeyed. But the daily reading and recital of the Granth is discontinued, for the Sikhs are the most uneducated class in the Punjab, and an occasional visit to the Sikh temple where the Granth is read aloud is all that the villager thinks necessary. Blue clothes have been discontinued save by the fanatical Akāli sect, as have been very generally the short drawers or Kachh. The prohibition of tobacco has had the unfortunate effect of inducing the Sikhs to take to hemp and opium, both of which are far more injurious than tobacco. The precepts which forbid the Sikh to venerate Brāhmans or to associate himself with Hindu worship are entirely neglected; and in the matter of the worship of local saints and deities, and of the employment of and reverence for Brāhmans, there is little, while in current superstitions and superstitious practices there is no difference between the Sikh villager and his Hindu brother.”391

5. Character of the Nānakpanthis and Sikh sects

It seems thus clear that if it had not been for the political and military development of the Sikh movement, it would in time have lost most of its distinctive features and have come to be considered as a Hindu sect of the same character, if somewhat more distinctive than those of the Nānakpanthis and Kabīrpanthis. But this development and the founding of the Sikh State of Lahore created a breach between the Sikhs and ordinary Hindus wider than that caused by their religious differences, as was sufficiently demonstrated during the Mutiny. In their origin both the Sikh and Nānakpanthi sects appear to have been mainly a revolt against the caste system, the supremacy of Brāhmans and the degrading mass of superstitions and reverence of idols and spirit-worship which the Brāhmans encouraged for their own profit. But while Nānak, influenced by the observation of Islamic monotheism, attempted to introduce a pure religion only, the aim of Govind was perhaps political, and he saw in the caste system an obstacle to the national movement which he desired to excite against the Muhammadans. So far as the abolition of caste was concerned, both reformers have, as has been seen, largely failed, the two sects now recognising caste, while their members revere Brāhmans like ordinary Hindus.

6. The Akālis

The Akālis or Nihangs are a fanatical order of Sikh ascetics. The following extract is taken from Sir E. Maclagan’s account of them:392

“The Akālis came into prominence very early by their stout resistance to the innovations introduced by the Bairāgi Banda after the death of Guru Govind; but they do not appear to have had much influence during the following century until the days of Mahārāja Ranjit Singh. They constituted at once the most unruly and the bravest portion of the very unruly and brave Sikh army. Their headquarters were at Amritsar, where they constituted themselves the guardians of the faith and assumed the right to convoke synods. They levied offerings by force and were the terror of the Sikh chiefs. Their good qualities were, however, well appreciated by the Mahārāja, and when there were specially fierce foes to meet, such as the Pathāns beyond the Indus, the Akālis were always to the front.

“The Akāli is distinguished very conspicuously by his dark-blue and checked dress, his peaked turban, often surmounted with steel quoits, and by the fact of his strutting about like Ali Bāba’s prince with his ‘thorax and abdomen festooned with curious cutlery.’ He is most particular in retaining the five Kakkas, and in preserving every outward form prescribed by Guru Govind Singh. Some of the Akālis wear a yellow turban underneath the blue one, leaving a yellow band across the forehead. The yellow turban is worn by many Sikhs at the Basant Panchmi, and the Akālis are fond of wearing it at all times. There is a couplet by Bhai Gurdās which says: