полная версия

полная версияProserpina, Volume 1

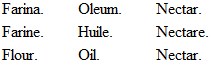

Our three separate substances will then be easily named in all three languages:

There is this farther advantage in keeping the third common term, that it leaves us the words Succus, Jus, Juice, for other liquid products of plants, watery, milky, sugary, or resinous,—often indeed important to man, but often also without either agreeable flavor or nutritious power; and it is therefore to be observed with care that we may use the word 'juice,' of a liquid produced by any part of a plant, but 'nectar,' only of the juices produced in its fruit.

6. But the good and pleasure of fruit is not in the juice only;—in some kinds, and those not the least valuable, (as the date,) it is not in the juice at all. We still stand absolutely in want of a word to express the more or less firm substance of fruit, as distinguished from all other products of a plant. And with the usual ill-luck,—(I advisedly think of it as demoniacal misfortune)—of botanical science, no other name has been yet used for such substance than the entirely false and ugly one of 'Flesh,'—Fr., 'Chair,' with its still more painful derivation 'Charnu,' and in England the monstrous scientific term, 'Sarco-carp.'

But, under the housewifery of Proserpina, since we are to call the juice of fruit, Nectar, its substance will be as naturally and easily called Ambrosia; and I have no doubt that this, with the other names defined in this chapter, will not only be found practically more convenient than the phrases in common use, but will more securely fix in the student's mind a true conception of the essential differences in substance, which, ultimately, depend wholly on their pleasantness to human perception, and offices for human good; and not at all on any otherwise explicable structure or faculty. It is of no use to determine, by microscope or retort, that cinnamon is made of cells with so many walls, or grape-juice of molecules with so many sides;—we are just as far as ever from understanding why these particular interstices should be aromatic, and these special parallelopipeds exhilarating, as we were in the savagely unscientific days when we could only see with our eyes, and smell with our noses. But to call each of these separate substances by a name rightly belonging to it through all the past variations of the language of educated man, will probably enable us often to discern powers in the thing itself, of affecting the human body and mind, which are indeed qualities infinitely more its own, than any which can possibly be extracted by the point of a knife, or brayed out with a mortar and pestle.

7. Thus, to take merely instance in the three main elements of which we have just determined the names,—flour, oil, and ambrosia;—the differences in the kinds of pleasure which the tongue received from the powderiness of oat-cake, or a well-boiled potato—(in the days when oat-cake and potatoes were!)—from the glossily-softened crispness of a well-made salad, and from the cool and fragrant amber of an apricot, are indeed distinctions between the essential virtues of things which were made to be tasted, much more than to be eaten; and in their various methods of ministry to, and temptation of, human appetites, have their part in the history, not of elements merely, but of souls; and of the soul-virtues, which from the beginning of the world have bade the barrel of meal not waste, nor the cruse of oil fail; and have planted, by waters of comfort, the fruits which are for the healing of nations.

8. And, again, therefore, I must repeat, with insistance, the claim I have made for the limitation of language to the use made of it by educated men. The word 'carp' could never have multiplied itself into the absurdities of endo-carps and epi-carps, but in the mouths of men who scarcely ever read it in its original letters, and therefore never recognized it as meaning precisely the same thing as 'fructus,' which word, being a little more familiar with, they would have scarcely abused to the same extent; they would not have called a walnut shell an intra-fruct—or a grape skin an extra-fruct; but again, because, though they are accustomed to the English 'fructify,' 'frugivorous'—and 'usufruct,' they are unaccustomed to the Latin 'fruor,' and unconscious therefore that the derivative 'fructus' must always, in right use, mean an enjoyed thing, they generalize every mature vegetable product under the term; and we find Dr. Gray coolly telling us that there is no fruit so "likely to be mistaken for a seed," as a grain of corn! a grain, whether of corn, or any other grass, being precisely the vegetable structure to which frutescent change is forever forbidden! and to which the word seed is primarily and perfectly applicable!—the thing to be sown, not grafted.

9. But to mark this total incapability of frutescent change, and connect the form of the seed more definitely with its dusty treasure, it is better to reserve, when we are speaking with precision, the term 'grain' for the seeds of the grasses: the difficulty is greater in French than in English: because they have no monosyllabic word for the constantly granular 'seed'; but for us the terms are all simple, and already in right use, only not quite clearly enough understood; and there remains only one real difficulty now in our system of nomenclature, that having taken the word 'husk' for the seed-vessel, we are left without a general word for the true fringe of a filbert, or the chaff of a grass. I don't know whether the French 'frange' could be used by them in this sense, if we took it in English botany. But for the present, we can manage well enough without it, one general term, 'chaff,' serving for all the grasses, 'cup' for acorns, and 'fringe' for nuts.

10. But I call this a real difficulty, because I suppose, among the myriads of plants of which I know nothing, there may be forms of the envelope of fruits or seeds which may, for comfort of speech, require some common generic name. One unreal difficulty, or shadow of difficulty, remains in our having no entirely comprehensive name for seed and seed-vessel together than that the botanists now use, 'fruit.' But practically, even now, people feel that they can't gather figs of thistles, and never speak of the fructification of a thistle, or of the fruit of a dandelion. And, re-assembling now, in one view, the words we have determined on, they will be found enough for all practical service, and in such service always accurate, and, usually, suggestive. I repeat them in brief order, with such farther explanation as they need.

11. All ripe products of the life of flowers consist essentially of the Seed and Husk,—these being, in certain cases, sustained, surrounded, or provided with means of motion, by other parts of the plant; or by developments of their own form which require in each case distinct names. Thus the white cushion of the dandelion to which its brown seeds are attached, and the personal parachutes which belong to each, must be separately described for that species of plants; it is the little brown thing they sustain and carry away on the wind, which must be examined as the essential product of the floret;—the 'seed and husk.'

12. Every seed has a husk, holding either that seed alone, or other seeds with it.

Every perfect seed consists of an embryo, and the substance which first nourishes that embryo; the whole enclosed in a sack or other sufficient envelope. Three essential parts altogether.

Every perfect husk, vulgarly pericarp, or 'round-fruit,'—(as periwig, 'round-wig,')—consists of a shell, (vulgarly endocarp,) rind, (vulgarly mesocarp,) and skin, (vulgarly epicarp); three essential parts altogether. But one or more of these parts may be effaced, or confused with another; and in the seeds of grasses they all concentrate themselves into bran.

13. When a husk consists of two or more parts, each of which has a separate shaft and volute, uniting in the pillar and volute of the flower, each separate piece of the husk is called a 'carpel.' The name was first given by De Candolle, and must be retained. But it continually happens that a simple husk divides into two parts corresponding to the two leaves of the embryo, as in the peach, or symmetrically holding alternate seeds, as in the pea. The beautiful drawing of the pea-shell with its seeds, in Rousseau's botany, is the only one I have seen which rightly shows and expresses this arrangement.

14. A Fruit is either the husk, receptacle, petal, or other part of a flower external to the seed, in which chemical changes have taken place, fitting it for the most part to become pleasant and healthful food for man, or other living animals; but in some cases making it bitter or poisonous to them, and the enjoyment of it depraved or deadly. But, as far as we know, it is without any definite office to the seed it contains; and the change takes place entirely to fit the plant to the service of animals.64

In its perfection, the Fruit Gift is limited to a temperate zone, of which the polar limit is marked by the strawberry, and the equatorial by the orange. The more arctic regions produce even the smallest kinds of fruit with difficulty; and the more equatorial, in coarse, oleaginous, or over-luscious masses.

15. All the most perfect fruits are developed from exquisite forms either of foliage or flower. The vine leaf, in its generally decorative power, is the most important, both in life and in art, of all that shade the habitations of men. The olive leaf is, without any rival, the most beautiful of the leaves of timber trees; and its blossom, though minute, of extreme beauty. The apple is essentially the fruit of the rose, and the peach of her only rival in her own colour. The cherry and orange blossom are the two types of floral snow.

16. And, lastly, let my readers be assured, the economy of blossom and fruit, with the distribution of water, will be found hereafter the most accurate test of wise national government.

For example of the action of a national government, rightly so called, in these matters, I refer the student to the Mariegolas of Venice, translated in Fors Clavigera; and I close this chapter, and this first volume of Proserpina, not without pride, in the words I wrote on this same matter eighteen years ago. "So far as the labourer's immediate profit is concerned, it matters not an iron filing whether I employ him in growing a peach, or in forging a bombshell. But the difference to him is final, whether, when his child is ill, I walk into his cottage, and give it the peach,—or drop the shell down his chimney, and blow his roof off."

INDEX I

DESCRIPTIVE NOMENCLATURE

Plants in perfect form are said, at page 26, to consist of four principal parts: root, stem, leaf, and flower. (Compare Chapter V., § 2.) The reader may have been surprised at the omission of the fruit from this list. But a plant which has borne fruit is no longer of 'perfect' form. Its flower is dead. And, observe, it is further said, at page 65, (and compare Chapter III., § 2,) that the use of the fruit is to produce the flower: not of the flower to produce the fruit. Therefore, the plant in perfect blossom, is itself perfect. Nevertheless, the formation of the fruit, practically, is included in the flower, and so spoken of in the fifteenth line of the same page.

Each of these four main parts of a plant consist normally of a certain series of minor parts, to which it is well to attach easily remembered names. In this section of my index I will not admit the confusion of idea involved by alphabetical arrangement of these names, but will sacrifice facility of reference to clearness of explanation, and taking the four great parts of the plant in succession, I will give the list of the minor and constituent parts, with their names as determined in Proserpina, and reference to the pages where the reasons for such determination are given, endeavouring to supply, at the same time, any deficiencies which I find in the body of the text.

I. The RootOrigin of the word Root 27

The offices of the root are threefold: namely, Tenure, Nourishment, and Animation 27-34

The essential parts of a Root are two: the Limbs and Fibres 33

I. The Limb is the gathered mass of fibres, or at least of fibrous substance, which extends itself in search of nourishment 32

II. The Fibre is the organ by which the nourishment is received 32

The inessential or accidental parts of roots, which are attached to the roots of some plants, but not to those of others, (and are, indeed, for the most part absent,) are three: namely, Store-Houses, Refuges, and Ruins 34

III. Store-houses contain the food of the future plant 34

IV. Refuges shelter the future plant itself for a time 35

V. Ruins form a basis for the growth of the future plant in its proper order 36

Root-Stocks, the accumulation of such ruins in a vital order 37

General questions relating to the office and chemical power of roots 38

The nomenclature of Roots will not be extended, in Proserpina, beyond the five simple terms here given: though the ordinary botanical ones—corm, bulb, tuber, etc.—will be severally explained in connection with the plants which they specially characterize.

II. The StemDerivation of word 137

The channel of communication between leaf and root 153

In a perfect plant it consists of three parts:

I. The Stem (Stemma) proper.—A growing or advancing shoot which sustains all the other organs of the plant 136

It may grow by adding thickness to its sides without advancing; but its essential characteristic is the vital power of Advance 136

It may be round, square, or polygonal, but is always roundly minded 136

Its structural power is Spiral 137

It is essentially branched; having subordinate leaf-stalks and flower-stalks, if not larger branches 139

It developes the buds, leaves, and flowers of the plant.

This power is not yet properly defined, or explained; and referred to only incidentally throughout the eighth chapter 134-138

II. The Leaf-Stalk (Cymba) sustains, and expands itself into, the Leaf 133, 134

It is essentially furrowed above, and convex below 134

It is to be called in Latin, the Cymba; in English, the Leaf-Stalk 135

III. The Flower-Stalk (Petiolus):

It is essentially round 130

It is usually separated distinctly at its termination from the flower 130, 131

It is to be called in Latin, Petiolus; in English, Flower-stalk 130

These three are the essential parts of a stem. But besides these, it has, when largely developed, a permanent form: namely,

IV. The Trunk.—A non-advancing mass of collected stem, arrested at a given height from the ground 139

The stems of annual plants are either leafy, as of a thistle, or bare, sustaining the flower or flower-cluster at a certain height above the ground. Receiving therefore these following names:–

V. The Virga.—The leafy stem of an annual plant, not a grass, yet growing upright 147

VI. The Virgula.—The leafless flower-stem of an annual plant, not a grass, as of a primrose or dandelion 147

VII. The Filum.—The running stem of a creeping plant

It is not specified in the text for use; but will be necessary; so also, perhaps, the Stelechos, or stalk proper (26), the branched stem of an annual plant, not a grass; one cannot well talk of the Virga of hemlock. The 'Stolon' is explained in its classical sense at page 158, but I believe botanists use it otherwise. I shall have occasion to refer to, and complete its explanation, in speaking of bulbous plants.

VIII. The Caudex.—The essentially ligneous and compact part of a stem 149

This equivocal word is not specified for use in the text, but I mean to keep it for the accumulated stems of inlaid plants, palms, and the like; for which otherwise we have no separate term.

IX. The Avena.—Not specified in the text at all; but it will be prettier than 'baculus,' which is that I had proposed, for the 'staff' of grasses. See page 179.

These ten names are all that the student need remember; but he will find some interesting particulars respecting the following three, noticed in the text:–

Stips.—The origin of stipend, stupid, and stump 148

Stipula.—The subtlest Latin term for straw 148

Caulis (Kale).—The peculiar stem of branched eatable vegetables 149

Canna.—Not noticed in the text; but likely to be sometimes useful for the stronger stems of grasses.

III. The LeafDerivation of word 26

The Latin form 'folium' 41

The Greek form 'petalos' 42

Veins and ribs of leaves, to be usually summed under the term 'rib' 44

Chemistry of leaves 46

The nomenclature of the leaf consists, in botanical books, of little more than barbarous, and, for the general reader, totally useless attempts to describe their forms in Latin. But their forms are infinite and indescribable except by the pencil. I will give central types of form in the next volume of Proserpina; which, so that the reader sees and remembers, he may call anything he likes. But it is necessary that names should be assigned to certain classes of leaves which are essentially different from each other in character and tissue, not merely in form. Of these the two main divisions have been already given: but I will now add the less important ones which yet require distinct names.

I. Apolline.—Typically represented by the laurel 51

II. Arethusan.—Represented by the alisma 52

It ought to have been noticed that the character of serration, within reserved limits, is essential to an Apolline leaf, and absolutely refused by an Arethusan one.

III. Dryad.—Of the ordinary leaf tissue, neither manifestly strong, nor admirably tender, but serviceably consistent, which we find generally to be the substance of the leaves of forest trees. Typically represented by those of the oak.

IV. Abietine.—Shaft or sword-shape, as the leaves of firs and pines.

V. Cressic.—Delicate and light, with smooth tissue, as the leaves of cresses, and clover.

VI. Salvian.—Soft and woolly, like miniature blankets, easily folded, as the leaves of sage.

VII. Cauline.—Softly succulent, with thick central ribs, as of the cabbage.

VIII. Aloeine.—Inflexibly succulent, as of the aloe or houseleek.

No rigid application of these terms must ever be attempted; but they direct the attention to important general conditions, and will often be found to save time and trouble in description.

IV. The FlowerIts general nature and function 65

Consists essentially of Corolla and Treasury 78

Has in perfect form the following parts:—

I. The Torus.—Not yet enough described in the text. It is the expansion of the extremity of the flower-stalk, in preparation for the support of the expanding flower 66, 224

II. The Involucrum.—Any kind of wrapping or propping condition of leafage at the base of a flower may properly come under this head; but the manner of prop or protection differs in different kinds, and I will not at present give generic names to these peculiar forms.

III. The Calyx (The Hiding-place).—The outer whorl of leaves, under the protection of which the real flower is brought to maturity. Its separate leaves are called Sepals 80

IV. The Corolla (The Cup).—The inner whorl of leaves, forming the flower itself. Its separate leaves are called Petals 71

V. The Treasury.—The part of the flower that contains its seeds.

VI. The Pillar.—The part of the flower above its treasury, by which the power of the pollen is carried down to the seeds 78

It consists usually of two parts—the Shaft and Volute 78

When the pillar is composed of two or more shafts, attached to separate treasury-cells, each cell with its shaft is called a Carpel 235

VII. The Stamens.—The parts of the flower which secrete its pollen 78

They consist usually of two parts, the Filament and Anther, not yet described.

VIII. The Nectary.—The part of the flower containing its honey, or any other special product of its inflorescence. The name has often been given to certain forms of petals of which the use is not yet known. No notice has yet been taken of this part of the flower in Proserpina.

These being all the essential parts of the flower itself, other forms and substances are developed in the seed as it ripens, which, I believe, may most conveniently be arranged in a separate section, though not logically to be considered as separable from the flower, but only as mature states of certain parts of it.

V. The SeedI must once more desire the reader to take notice that, under the four sections already defined, the morphology of the plant is to be considered as complete, and that we are now only to examine and name, farther, its product; and that not so much as the germ of its own future descendant flower, but as a separate substance which it is appointed to form, partly to its own detriment, for the sake of higher creatures. This product consists essentially of two parts: the Seed and its Husk.

I. The Seed.—Defined 220

It consists, in its perfect form, of three parts 222

These three parts are not yet determinately named in the text: but I give now the names which will be usually attached to them.

A. The Sacque.—The outside skin of a seed 221

B. The Nutrine.—A word which I coin, for general applicability, whether to the farina of corn, the substance of a nut, or the parts that become the first leaves in a bean 221

C. The Germ.—The origin of the root 221

II. The Husk.—Defined 222

Consists, like the seed when in perfect form, of three parts.

A. The Skin.—The outer envelope of all the seed structures 222

B. The Rind.—The central body of the Husk. 222-235

C. The Shell.—Not always shelly, yet best described by this general term; and becoming a shell, so called, in nuts, peaches, dates, and other such kernel-fruits 222

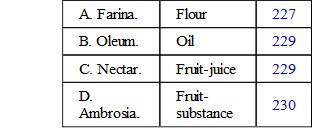

The products of the Seed and Husk of Plants, for the use of animals, are practically to be massed under the three heads of Bread, Oil, and Fruit. But the substance of which bread is made is more accurately described as Farina; and the pleasantness of fruit to the taste depends on two elements in its substance: the juice, and the pulp containing it, which may properly be called Nectar and Ambrosia. We have therefore in all four essential products of the Seed and Husk—

227, 229, 230.

Besides these all-important products of the seed, others are formed in the stems and leaves of plants, of which no account hitherto has been given in Proserpina. I delay any extended description of these until we have examined the structure of wood itself more closely; this intricate and difficult task having been remitted (p. 195) to the days of coming spring; and I am well pleased that my younger readers should at first be vexed with no more names to be learned than those of the vegetable productions with which they are most pleasantly acquainted: but for older ones, I think it well, before closing the present volume, to indicate, with warning, some of the obscurities, and probable fallacies, with which this vanity of science encumbers the chemistry, no less than the morphology, of plants.

Looking back to one of the first books in which our new knowledge of organic chemistry began to be displayed, thirty years ago, I find that even at that period the organic elements which the cuisine of the laboratory had already detected in simple Indigo, were the following:—

Isatine, Bromisatine, Bidromisatine;

Chlorisatine, Bichlorisatine;

Chlorisatyde, Bichlorisatyde;

Chlorindine, Chlorindoptene, Chlorindatmit;

Chloranile, Chloranilam, and, Chloranilammon.

And yet, with all this practical skill in decoction, and accumulative industry in observation and nomenclature, so far are our scientific men from arriving, by any decoctive process of their own knowledge, at general results useful to ordinary human creatures, that when I wish now to separate, for young scholars, in first massive arrangement of vegetable productions, the Substances of Plants from their Essences; that is to say, the weighable and measurable body of the plant from its practically immeasurable, if not imponderable, spirit, I find in my three volumes of close-printed chemistry, no information what ever respecting the quality of volatility in matter, except this one sentence:—