полная версия

полная версияLove's Meinie: Three Lectures on Greek and English Birds

2. Food. Small thin-skinned crustacea, and aquatic surface-insects.

3. Form and flight. Stout, for a sea-bird; and they don't care to fly, preferring to swim out of danger. Body 7 to 8 inches long; wings, from carpal joint to end, 4¾,—say 5. These quarters of inches, are absurd pretenses to generalize what varies in every bird. 8 inches long, by 10 across the wings open, is near enough. In future, the brief notification 8 × 10, 5 × 7, or the like, will enough express a bird's inches, unless it possess decorative appendage of tail, which must be noted separately.

4. Foot. Chestnut-leaved in front toes, the lobes slightly serrated on the edges. Hind toe without membrane. Color of foot, always black.

5. Beak. Long, slender, straight. (How long? Drawn as about a fifth of the bird's length—say an inch, or a little over.) Upper mandible slightly curved down at the point. In Titania arctica, the beak is longer and more slender.

6. Voice. A sharp, short cry, not conceived by me enough to spell any likeness of it.

7. Temper. Gentle, passing into stupid, (it seems to me); one, in meditative travel, lets itself be knocked down by a gardener with his spade.

8. Nest. Little said of it, the bird breeding chiefly in the North. Among marshes, it is of weeds and grass; but among icebergs, of what?

9. Eggs. Pear-shape; narrow ends together in nest; never more than four.

10. Brood. No account of.

11. Feathers. Mostly gray, passing into brown in summer, varied with white on margin. Reddish chestnut or bay bodice—well oiled or varnished.

12. Uses. Fortunately, at present, unknown.

VRALLUS AQUATICUS. WATER-RAIL116. Thus far, we have got for representatives of our dabchick group, eight species of little birds—namely, two Torrent-ouzels, three Lily-ouzels, one Grebe, and two Titanias. And these we associate, observe, not for any specialty of feature in them, but for common character, habit, and size; so that, if perchance a child playing by any stream, or on the sea-sands, perceives a companionable bird dabbling in an equally childish and pleasant manner, he may not have to look through half a dozen volumes of ornithology to find it; but may be pretty sure it has been one of these eight. And having once fastened the characters of these well in his mind, he may with ease remember that the little grebe is the least of a family of chestnut-leaf-footed, and sharp-billed creatures, which yet in size, color, and diving power, go necessarily among Ducks, and cannot be classed with Dabblers; though it must be always as distinctly kept in mind that a duck proper has a flat beak, and a fully webbed foot.

Again, he may recollect that with these leaf-footed ducks of the calm and fresh waters, must be associated the leaf-footed or fringe-footed ducks of the sea;—'phalaropes,' which by their short wings connect themselves with many clumsy marine creatures, on their way to become seals instead of birds; and that I have kept the two little Titanias out of this class, not merely for their niceness, but because they are not short-winged in any vulgar degree, but seem to have wings about as long as a sandpiper's;—and indeed I had put the purple sandpiper, Arquatella maritima, with them, in my own folio; only as the Arquatella's feet are not chestnutty, she had better go with her own kind in our notes on them.

117. But there are yet two birds, which I think well to put with our eight dabchicks, though they are much larger than any of them,—partly because of their disposition, and partly because of their plumage,—the water-rail, and water-hen. Modern science, with instinctive horror of all that is pretty to see, or easy to remember, entirely rejects the plumage, as any element or noticeable condition of bird-kinds; nor have I ever yet tried to make it one myself; yet there are certain qualities of downiness in ducks, fluffiness in owls, spottiness in thrushes, patchiness in pies, bronzed or rusty luster in cocks, and pearly iridescence in doves, which I believe may be aptly brought into connection with other defining characters; and when we find an entirely similar disposition of plumage, and nearly the same form, in two birds, I do not think that mere difference in size should far separate them.

Bewick, accordingly, calls the water-rail the 'Brook-ouzel,' and puts it between the little crake and the water-ouzel; but he does not say a word of its living by brooks,—only 'in low wet places.' Buffon, however, takes it with the land-rail; Gould and Yarrell put it between the little crake and water-hen. Gould's description of it is by no means clear to me:—he first says it is, in action, as much "like a rat as a bird;" then that it "bounds like a ball," (before the nose of the spaniel); and lastly, in the next sentence, speaks of it as "this lath-like bird"! It is as large as a bantam, but can run, like the Allegretta, on floating leaves; itself, weighing about four ounces and a half (Bewick), and rarely uses the wing, flying very slowly. I imagine the 'lath-like' must mean, like the more frequent epithet 'compressed,' that the bird's body is vertically thin, so as to go easily between close reeds.

118. We will try our twelve questions again.

1. Country. Equally numerous in every part of Europe, in Africa, India, China, and Japan; yet hardly anybody seems to have seen it. Living, however, "near the perennial fountains" (wherever those may be;—it sounds like the garden of Eden!) "during the greater part of the winter, the birds pass Malta in spring and autumn, and have been seen fifty leagues at sea off the coast of Portugal" (Buffon); but where coming from, or going to, is not told. Tunis is the most southerly place named by Yarrell.

2. Food. Anything small enough to be swallowed, that lives in mud or water.

3. Form and flight. I am puzzled, as aforesaid, between its likeness to a ball, and a lath. Flies heavily and unwillingly, hanging its legs down.

4. Foot. Long-toed and flexible.

5. Beak. Sharp and strong, some inch and a half long, showing distinctly the cimeter-curve of a gull's, near the point.

6. Voice. No account of.

7. Temper. Quite easily tamable, though naturally shy. Feeds out of the hand in a day or two, if fed regularly in confinement.

8. Nest. "Slight, of leaves and strips of flags" (Gould); "of sedge and grass, rarely found," (Yarrell). Size not told.

9. Eggs. Eight or nine! cream-white, with rosy yolk!! rather larger than a blackbird's!!!

10. Brood. Velvet black, with white bills; hunting with the utmost activity from the minute they are hatched.

11. Feathers. Brown on the back, a beautiful warm ash gray on the breast, and under the wings transverse stripes of very dark gray and white. The disposition of pattern is almost exactly the same as in the Allegretta.

12. Uses. By many thought delicious eating. (Bewick.) The fact is, or seems to me, that this entire group of marsh birds is meant to become to us the domestic poultry of marshy land; and I imagine that by proper irrigation and care, many districts of otherwise useless bog and sand, might be made more profitable to us than many fishing-grounds.

VIPULLA AQUATICA. WATER-HEN(Gallinula Chloropus.—Pennant, Bewick, Gould, and Yarrell.)119. 'Green-footed little cock, or hen,' that is to say, in English; only observe, if you call the Fringe-foot a Phalarope, you ought in consistency to call the Green-foot a Chlorope. Their feet are not only notable for greenness, but for size: they are very ugly, having the awkward and ill-used look of the feet of Scratchers, while a trace of beginning membrane connects them with the fringe-foots.

Their proper name would be Marsh-cock, which would enough distinguish them from the true Moor-cock or Black-cock. 'Moat-cock' would be prettier, and characteristic; for in the old English days they used to live much in the moats of manor-houses; mine is the name nearest to the familiar one; only note there is no proper feminine of 'pullus,' and I use the adjective 'pulla' to express the dark color.

It is a dark-brown bird, according to the colored pictures—iron gray, Buffon says, with white stripes of little order on the bodice, clumsy feet and bill, but makes up for all ungainliness by its gentle and intelligent mind; and seems meant for a useful possession to mankind all over the world, for it lives in Siberia and New Zealand; in Senegal and Jamaica; in Scotland, Switzerland, and Prussia; in Corfu, Crete, and Trebizond; in Canada, and at the Cape. I find no account of its migrations, and one would think that a bird which usually flies "dip, dip, dipping with its toes, and leaving a track along the water like that of a stone at 'ducks and drakes'" (Yarrell), would not willingly adventure itself on the Atlantic. It must have a kind of human facility in adapting itself to climate, as it has human domesticity of temper, with curious fineness of sagacity and sympathies in taste. A family of them, petted by a clergyman's wife, were constantly adding materials to their nest, and "made real havoc in the flower-garden,—for though straw and leaves are their chief ingredients, they seem to have an eye for beauty, and the old hen has been seen surrounded with a brilliant wreath of scarlet anemones." Thus Bishop Stanley, whose account of the bird is full of interesting particulars. This aesthetic water-hen, with her husband, lived at Cheadle, in Staffordshire, in the rectory moat, for several seasons, "always however leaving it in the spring," (for Scotland, supposably?): being constantly fed, the pair became quite tame, built their nest in a thorn-bush covered with ivy which had fallen into the water; and "when the young are a few days old, the old ones bring them up close to the drawing-room window, where they are regularly fed with wheat; and, as the lady of the house pays them the greatest attention, they have learned to look up to her as their natural protectress and friend; so much so, that one bird in particular, which was much persecuted by the rest, would, when attacked, fly to her for refuge; and whenever she calls, the whole flock, as tame as barn-door fowls, quit the water, and assemble round her, to the number of seventeen. (November, 1833.)

120. "They have also made other friends in the dogs belonging to the family, approaching them without fear, though hurrying off with great alarm on the appearance of a strange dog.

"The position of the water, together with the familiarity of these birds, has afforded many interesting particulars respecting their habits.

"They have three broods in a season—the first early in April; and they begin to lay again when the first hatch is about a fortnight old. They lay eight or nine eggs, and sit about three weeks,—the cock alternately with the hen. The nest in the thorn-bush is placed usually so high above the surface of the water, they cannot climb into it again; but, as a substitute, within an hour after they leave the nest, the cock bird builds a larger and more roomy nest for them, with sedges, at the water's edge, which they can enter or retire from at pleasure. For about a month they are fed by the old birds, but soon become very active in taking flies and water-insects. Immediately on the second hatch coming out, the young ones of the first hatch assist the old ones in feeding and hovering over them, leading them out in detached parties, and making additional nests for them, similar to their own, on the brink of the moat.

"But it is not only in their instinctive attachments and habits that they merit notice; the following anecdote proves that they are gifted with a sense of observation approaching to something very like reasoning faculties.

"At a gentleman's house in Staffordshire, the pheasants are fed out of one of those boxes described in page 287, the lid of which rises with the pressure of the pheasant standing on the rail in front of the box. A water-hen observing this, went and stood upon the rail as soon as the pheasant had quitted it; but the weight of the bird being insufficient to raise the lid of the box, so as to enable it to get at the corn, the water-hen kept jumping on the rail to give additional impetus to its weight: this partially succeeded, but not to the satisfaction of the sagacious bird. Accordingly it went off, and soon returning with a bird of its own species, the united weight of the two had the desired effect, and the successful pair enjoyed the benefit of their ingenuity.

"We can vouch for the truth of this singular instance of penetration, on the authority of the owner of the place where it occurred, and who witnessed the fact."

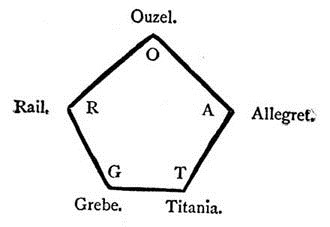

121. But although in these sagacities, and teachablenesses, the bird has much in common with land poultry, it seems not a link between these and water-fowl; but to be properly placed by the ornithologists between the rail and the coot: this latter being the largest of the fringefoots, singularly dark in color, and called 'fulica' (sooty), or, with insistence, 'fulica atra' (black sooty), or even 'fulica aterrima' (blackest sooty). 'Coot' is said by Johnson to be Dutch; and that it became 'cotée' in French; but I cannot find cotée in my French dictionary. In the meantime, putting the coot and water-hen aside for future better knowledge, we may be content with the pentagonal group of our dabchicks—passing at each angle into another tribe, thus,—(if people must classify, they at least should also map). Take the Ouzel, Allegret, Grebe, Fairy, and Rail, and, only giving the Fairy her Latin name, write their fourpenny-worth of initial letters (groat) round a pentagon set on its base, putting the Ouzel at the top angle,—so. Then, the Ouzels pass up into Blackbirds, the Rails to the left into Woodcocks, the Allegrets to the right into Plovers, the Grebes, down left, into Ducks, and the Titanias, down right, into Gulls. And there's a bit of pentagonal Darwinism for you, if you like it, and learn it, which will be really good for something in the end, or the five ends.

122. And for the bliss of classification pure, with no ends of any sort or any number, referring my reader to the works of ornithologists in general, and for what small portion of them he may afterwards care to consult, to my Appendix, I will end this lecture, and this volume, with the refreshment for us of a piece of perfect English and exquisite wit, falling into verse,—the Chorus of the Birds, in Mr. Courthope's Paradise of them,—a book lovely, and often faultless, in most of its execution, but little skilled or attractive in plan, and too thoughtful to be understood without such notes as a good author will not write on his own work; partly because he has not time, and partly because he always feels that if people won't look for his meaning, they should not be told it. My own special function, on the contrary, is, and always has been, that of the Interpreter only, in the 'Pilgrim's Progress;' and I trust that Mr. Courthope will therefore forgive my arranging his long cadence of continuous line so as to come symmetrically into my own page, (thus also enforcing, for the inattentive, the rhymes which he is too easily proud to insist on,) and my division of the whole chorus into equal strophe and antistrophe of six lines each, in which, counting from the last line of the stanza, the reader can easily catch the word to which my note refers.

123.

We wish to declare,How the birds of the airAll high institutions designed,And, holding in aweArt, Science, and Law,Delivered the same to mankind.To begin with; of oldMan went naked, and cold,Whenever it pelted or froze,Till we showed him how feathersWere proof against weathers,With that, he bethought him of hose.And next, it was plain,That he, in the rain,Was forced to sit dripping and blind,While the Reed-warbler swungIn a nest, with her youngDeep sheltered, and warm, from the wind.So our homes in the boughsMade him think of the House;And the Swallow, to help him invent,Revealed the best wayTo economize clay,And bricks to combine with cement.The knowledge withalOf the Carpenter's awl,Is drawn from the Nuthatch's bill;And the Sand-Martin's painsIn the hazel-clad lanesInstructed the Mason to drill.Is there one of the Arts,More dear to men's hearts?To the bird's inspiration they owe it;For the Nightingale firstSweet music rehearsed,Prima-Donna, Composer, and Poet.The Owl's dark retreatsShowed sages the sweetsOf brooding, to spin, or unravelFine webs in one's brain,Philosophical—vain;The Swallows,—the pleasures of travel.Who chirped in such strainOf Greece, Italy, SpainAnd Egypt, that men, when they heard,Were mad to fly forth,From their nests in the North,And follow—the tail of the Bird.Besides, it is true,To our wisdom is dueThe knowledge of Sciences all;And chiefly, those rareMetaphysics of AirMen 'Meteorology' call,And men, in their words,Acknowledge the Birds'Erudition in weather and star;For they say, "'Twill be dry,—The swallow is high,"Or, "Rain, for the Chough is afar."'Twas the Rooks who taught menVast pamphlets to penUpon social compact and law,And Parliaments hold,As themselves did of old,Exclaiming 'Hear, Hear,' for 'Caw, Caw.'And whence arose Love?Go, ask of the Dove,Or behold how the Titmouse, unresting,Still early and lateEver sings by his mate,To lighten her labors of nesting.Their bonds never gall,Though the leaves shoot, and fall,And the seasons roll round in their course,For their marriage, each year,Grows more lovely and dear;And they know not decrees of Divorce.That these things are truthWe have learned from our youth,For our hearts to our customs incline,As the rivers that rollFrom the fount of our soul,Immortal, unchanging, divine.Man, simple and old,In his ages of gold,Derived from our teaching true light,And deemed it his praiseIn his ancestors' waysTo govern his footsteps aright.But the fountain of woes,Philosophy, rose;And, what between reason and whim,He has splintered our rulesInto sections and schools,So the world is made bitter, for him.But the birds, since on earthThey discovered the worthOf their souls, and resolved with a vowNo custom to change,For a new, or a strange,Have attained unto Paradise, now.Line 9. Pelted, said of hail, not rain. Felt by nakedness, in a more severe manner than mere rain.

11. 'Weathers,' i.e., both weathers—hail and cold: the armor of the feathers against hail; the down of them against cold. See account of Feather-mail in 'Laws of Fésole,' chap, vi., p. 53, with the first and fifth plates, and figure 15.

15. Blind. By the beating of the rain in his face. In hail, there is real danger and bruising, if the hail be worth calling so, for the whole body; while in rain, if it be rain also worth calling rain, the great plague is the beating and drenching in the face.

16. Swung. Opposed to 'sit' in previous line. The human creature, though it sate steady on this unshakable earth, had no house over its head. The bird, that lived on the tremblingest and weakest of bending things, had her nest on it, in which even her infinitely tender brood were deep sheltered and warm, from the wind. It is impossible to find a lovelier instance of pure poetical antithesis.

20. House. Again antithetic to the perfect word 'Home' in the line before. A house is exactly, and only, half-way to a 'home.' Man had not yet got so far as even that! and had lost, the chorus satirically imply, even the power of getting the other half, ever, since his "She gave me of the tree."

24. Bricks. The first bad inversion permitted, for "to combine bricks with cement." In my Swallow lecture I had no time to go into the question of her building materials; the point is, however, touched upon in the Appendix (pp. 110, 112, and note).

30. 'Drill,' for 'quarry out,' 'tunnel,' etc., the best general term available.

36. Composer of the music; Poet of the meaning.

Compare, and think over, the Bullfinch's nest, etc., § 48 to 61 of 'Eagle's Nest.'

In modern music the meaning is, I believe, by the reputed masters omitted.

39. To Spin, or unravel. Synthesis and analysis, in the vulgar Greek slang.

46. Mad. Compare Byron of the English in his day. "A parcel of staring boobies who go about gaping and wishing to be at once cheap and magnificent. A man is a fool now, who travels in France or Italy, till that tribe of wretches be swept home again. In two or three years, the first rush will be over, and the Continent will be roomy and agreeable." (Life, vol. ii., p. 319.) For sketches of the English of seventeen years later, at the same spots (Wengern Alp and Interlachen), see, if you can see, in any library, public or private, at Geneva, Topffer's 'Excursions dans les Alpes, 1832.' Douzième, Treizième, and Quatorzième Journée.

48. The Tail. Mr. Courthope does not condescend to italicize his pun; but a swallow-tailed and adder-tongued pun like this must be paused upon. Compare Mr. Murray's Tale of the Town of Lucca, to be seen between the arrival of one train and the departure of the next,—nothing there but twelve churches and a cathedral,—mostly of the tenth to thirteenth century.

60. Afar. I did not know of this weather sign; nor, I suppose, did the Duke of Hamilton's keeper, who shot the last pair of Choughs on Arran in 1863. ('Birds of the West of Scotland,' p. 165.) I trust the climate has wept for them; certainly our Coniston clouds grow heavier, in these last years.

63. Social. Rightly sung by the Birds in three syllables; but the lagging of the previous line (probably intentional, but not pleasant,) makes the lightness of this one a little dangerous for a clumsy reader. The 'i-al' of 'social' does not fill the line as two full short syllables, else the preceding word should have been written 'on,' not 'upon.' The five syllables, rightly given, just take the time of two iambs; but there are readers rude enough to accent the 'on' of upon, and take 'social' for two short syllables.

64. Hold. Short for 'to hold'—but it is a licentious construction, so also, in next line, 'themselves' for 'they themselves.' The stanza is on the whole the worst in the poem, its irony and essential force being much dimmed by obscure expression, and even slightly staggering continuity of thought. The Rooks may be properly supposed to have taught men to dispute, but not to write. The Swallow teaches building, literally, and the Owl moping, literally; but the Rook does not teach pamphleteering literally. And the 'of old' is redundant, for rhyme's sake, since Rooks hold parliaments now as much as ever they did.

76. Each Year. I doubt the fact; and too sadly suspect that birds take different mates. What a question to have to ask at this time of day and year!

82. Rivers. Read slowly. The 'customs' are rivers that 'go on forever' flowing from the fount of the soul. The Heart drinks of them, as of waterbrooks.

92. Philosophy. The author should at least have given a note or two to explain the sense in which he uses words so wide as this. The philosophy which begins in pride, and concludes in malice, is indeed a fountain—though not the fountain—of woes, to mankind. But true philosophy such as Fénelon's or Sir Thomas More's, is a well of peace.

98. Worth. Again, it is not clearly told us what the author means by the worth of a bird's soul, nor how the birds learned it. The reader is left to discern, and collect for himself—with patience such as not one in a thousand now-a-days possesses, the opposition between the "fount of our soul" (line 83) and fountain of philosophy.

124. I could willingly enlarge on these last two stanzas, but think my duty will be better done to the poet if I quote, for conclusion, two lighter pieces of his verse, which will require no comment, and are closer to our present purpose. The first,—the lament of the French Cook in purgatory,—has, for once, a note by the author, giving M. Soyer's authority for the items of the great dish,—"symbol of philanthropy, served at York during the great commemorative banquet after the first exhibition." The commemorative soul of the tormented Chef—always making a dish like it, of which nobody ever eats—sings thus:—

"Do you veeshTo hear before you taste, of de hundred-guinea deesh?Has it not been sung by every knife and fork,'L'extravagance culinaire à l'Alderman,' at York?Vy, ven I came here, eighteen Octobers seence,I dis deesh was making for your Royal Preence,Ven half de leeving world, cooking all de others,Swore an oath hereafter, to be men and brothers.All de leetle Songsters in de voods dat build,Hopped into the kitchen asking to be kill'd;All who in de open furrows find de seeds,Or de mountain berries, all de farmyard breeds,—Ha—I see de knife, vile de deesh it shapens,Vith les petits noix, of four-and-twenty capons,Dere vere dindons, fatted poulets, fowls in plenty,Five times nine of partridges, and of pheasants twenty;Ten grouse, that should have had as many covers,All in dis one deesh, with six preety plovers,Forty woodcocks, plump, and heavy in the scales,Pigeons dree good dozens, six-and-dirty quails,Ortulans, ma foi, and a century of snipes,But de preetiest of dem all was twice tree dozen pipesOf de melodious larks, vich each did clap the ving,And veeshed de pie vas open, dat dey all might sing!"125. There are stiff bits of prosody in these verses,—one or two, indeed, quite unmanageable,—but we must remember that French meter will not read into ours. The last piece I will give flows very differently. It is in express imitation of Scott—but no nobler model could be chosen; and how much better for minor poets sometimes to write in another's manner, than always to imitate their own.