полная версия

полная версияThe Seven Lamps of Architecture

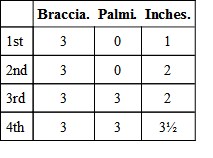

The side of that church has three stories of arcade, diminishing in height in bold geometrical proportion, while the arches, for the most part, increase in number in arithmetical, i. e. two in the second arcade, and three in the third, to one in the first. Lest, however, this arrangement should be too formal, of the fourteen arches in the lowest series, that which contains the door is made larger than the rest, and is not in the middle, but the sixth from the West, leaving five on one side and eight on the other. Farther: this lowest arcade is terminated by broad flat pilasters, about half the width of its arches; but the arcade above is continuous; only the two extreme arches at the west end are made larger than all the rest, and instead of coming, as they should, into the space of the lower extreme arch, take in both it and its broad pilaster. Even this, however, was not out of order enough to satisfy the architect's eye; for there were still two arches above to each single one below: so at the east end, where there are more arches, and the eye might be more easily cheated, what does he do but narrow the two extreme lower arches by half a braccio; while he at the same time slightly enlarged the upper ones, so as to get only seventeen upper to nine lower, instead of eighteen to nine. The eye is thus thoroughly confused, and the whole building thrown into one mass, by the curious variations in the adjustments of the superimposed shafts, not one of which is either exactly in nor positively out of its place; and, to get this managed the more cunningly, there is from an inch to an inch and a half of gradual gain in the space of the four eastern arches, besides the confessed half braccio. Their measures, counting from the east, I found as follows:—

The upper arcade is managed on the same principle; it looks at first as if there were three arches to each under pair; but there are, in reality, only thirty-eight (or thirty-seven, I am not quite certain of this number) to the twenty-seven below; and the columns get into all manner of relative positions. Even then, the builder was not satisfied, but must needs carry the irregularity into the spring of the arches, and actually, while the general effect is of a symmetrical arcade, there is not one of the arches the same in height as another; their tops undulate all along the wall like waves along a harbor quay, some nearly touching the string course above, and others falling from it as much as five or six inches.

XIV. Let us next examine the plan of the west front of St. Mark's at Venice, which, though in many respects imperfect, is in its proportions, and as a piece of rich and fantastic color, as lovely a dream as ever filled human imagination. It may, perhaps, however, interest the reader to hear one opposite opinion upon this subject, and after what has been urged in the preceding pages respecting proportion in general, more especially respecting the wrongness of balanced cathedral towers and other regular designs, together with my frequent references to the Doge's palace, and campanile of St. Mark's, as models of perfection, and my praise of the former especially as projecting above its second arcade, the following extracts from the journal of Wood the architect, written on his arrival at Venice, may have a pleasing freshness in them, and may show that I have not been stating principles altogether trite or accepted.

"The strange looking church, and the great ugly campanile, could not be mistaken. The exterior of this church surprises you by its extreme ugliness, more than by anything else."

"The Ducal Palace is even more ugly than anything I have previously mentioned. Considered in detail, I can imagine no alteration to make it tolerable; but if this lofty wall had been set back behind the two stories of little arches, it would have been a very noble production."

After more observations on "a certain justness of proportion," and on the appearance of riches and power in the church, to which he ascribes a pleasing effect, he goes on: "Some persons are of opinion that irregularity is a necessary part of its excellence. I am decidedly of a contrary opinion, and am convinced that a regular design of the same sort would be far superior. Let an oblong of good architecture, but not very showy, conduct to a fine cathedral, which should appear between two lofty towers and have two obelisks in front, and on each side of this cathedral let other squares partially open into the first, and one of these extend down to a harbor or sea shore, and you would have a scene which might challenge any thing in existence."

Why Mr. Wood was unable to enjoy the color of St. Mark's, or perceive the majesty of the Ducal Palace, the reader will see after reading the two following extracts regarding the Caracci and Michael Angelo.

"The pictures here (Bologna) are to my taste far preferable to those of Venice, for if the Venetian school surpass in coloring, and, perhaps, in composition, the Bolognese is decidedly superior in drawing and expression, and the Caraccis shine here like Gods."

"What is it that is so much admired in this artist (M. Angelo)? Some contend for a grandeur of composition in the lines and disposition of the figures; this, I confess, I do not comprehend; yet, while I acknowledge the beauty of certain forms and proportions in architecture, I cannot consistently deny that similar merits may exist in painting, though I am unfortunately unable to appreciate them."

I think these passages very valuable, as showing the effect of a contracted knowledge and false taste in painting upon an architect's understanding of his own art; and especially with what curious notions, or lack of notions, about proportion, that art has been sometimes practised. For Mr. Wood is by no means unintelligent in his observations generally, and his criticisms on classical art are often most valuable. But those who love Titian better than the Caracci, and who see something to admire in Michael Angelo, will, perhaps, be willing to proceed with me to a charitable examination of St. Mark's. For, although, the present course of European events affords us some chance of seeing the changes proposed by Mr. Wood carried into execution, we may still esteem ourselves fortunate in having first known how it was left by the builders of the eleventh century.

XV. The entire front is composed of an upper and lower series of arches, enclosing spaces of wall decorated with mosaic, and supported on ranges of shafts of which, in the lower series of arches, there is an upper range superimposed on a lower. Thus we have five vertical divisions of the façade; i.e. two tiers of shafts, and the arched wall they bear, below; one tier of shafts, and the arched wall they bear, above. In order, however, to bind the two main divisions together, the central lower arch (the main entrance) rises above the level of the gallery and balustrade which crown the lateral arches.

The proportioning of the columns and walls of the lower story is so lovely and so varied, that it would need pages of description before it could be fully understood; but it may be generally stated thus: The height of the lower shafts, upper shafts, and wall, being severally expressed by a, b, and c, then a:c::c:b (a being the highest); and the diameter of shaft b is generally to the diameter of shaft a as height b is to height a, or something less, allowing for the large plinth which diminishes the apparent height of the upper shaft: and when this is their proportion of width, one shaft above is put above one below, with sometimes another upper shaft interposed: but in the extreme arches a single under shaft bears two upper, proportioned as truly as the boughs of a tree; that is to say, the diameter of each upper = 2/3 of lower. There being thus the three terms of proportion gained in the lower story, the upper, while it is only divided into two main members, in order that the whole height may not be divided into an even number, has the third term added in its pinnacles. So far of the vertical division. The lateral is still more subtle. There are seven arches in the lower story; and, calling the central arch a, and counting to the extremity, they diminish in the alternate order a, c, b, d. The upper story has five arches, and two added pinnacles; and these diminish in regular order, the central being the largest, and the outermost the least. Hence, while one proportion ascends, another descends, like parts in music; and yet the pyramidal form is secured for the whole, and, which was another great point of attention, none of the shafts of the upper arches stand over those of the lower.

XVI. It might have been thought that, by this plan, enough variety had been secured, but the builder was not satisfied even thus: for—and this is the point bearing on the present part of our subject—always calling the central arch a, and the lateral ones b and c in succession, the northern b and c are considerably wider than the southern b and c, but the southern d is as much wider than the northern d, and lower beneath its cornice besides; and, more than this, I hardly believe that one of the effectively symmetrical members of the façade is actually symmetrical with any other. I regret that I cannot state the actual measures. I gave up the taking them upon the spot, owing to their excessive complexity, and the embarrassment caused by the yielding and subsidence of the arches.

Do not let it be supposed that I imagine the Byzantine workmen to have had these various principles in their minds as they built. I believe they built altogether from feeling, and that it was because they did so, that there is this marvellous life, changefulness, and subtlety running through their every arrangement; and that we reason upon the lovely building as we should upon some fair growth of the trees of the earth, that know not their own beauty.

XVII. Perhaps, however, a stranger instance than any I have yet given, of the daring variation of pretended symmetry, is found in the front of the Cathedral of Bayeux. It consists of five arches with steep pediments, the outermost filled, the three central with doors; and they appear, at first, to diminish in regular proportion from the principal one in the centre. The two lateral doors are very curiously managed. The tympana of their arches are filled with bas-reliefs, in four tiers; in the lowest tier there is in each a little temple or gate containing the principal figure (in that on the right, it is the gate of Hades with Lucifer). This little temple is carried, like a capital, by an isolated shaft which divides the whole arch at about 2/3 of its breadth, the larger portion outmost; and in that larger portion is the inner entrance door. This exact correspondence, in the treatment of both gates, might lead us to expect a correspondence in dimension. Not at all. The small inner northern entrance measures, in English feet and inches, 4 ft. 7 in. from jamb to jamb, and the southern five feet exactly. Five inches in five feet is a considerable variation. The outer northern porch measures, from face shaft to face shaft, 13 ft. 11 in., and the southern, 14 ft. 6 in.; giving a difference of 7 in. on 14 ½ ft. There are also variations in the pediment decorations not less extraordinary.

XVIII. I imagine I have given instances enough, though I could multiply them indefinitely, to prove that these variations are not mere blunders, nor carelessnesses, but the result of a fixed scorn, if not dislike, of accuracy in measurements; and, in most cases, I believe, of a determined resolution to work out an effective symmetry by variations as subtle as those of Nature. To what lengths this principle was sometimes carried, we shall see by the very singular management of the towers of Abbeville. I do not say it is right, still less that it is wrong, but it is a wonderful proof of the fearlessness of a living architecture; for, say what we will of it, that Flamboyant of France, however morbid, was as vivid and intense in its animation as ever any phase of mortal mind; and it would have lived till now, if it had not taken to telling lies. I have before noticed the general difficulty of managing even lateral division, when it is into two equal parts, unless there be some third reconciling member. I shall give, hereafter, more examples of the modes in which this reconciliation is effected in towers with double lights: the Abbeville architect put his sword to the knot perhaps rather too sharply. Vexed by the want of unity between his two windows he literally laid their heads together, and so distorted their ogee curves, as to leave only one of the trefoiled panels above, on the inner side, and three on the outer side of each arch. The arrangement is given in Plate XII. fig. 3. Associated with the various undulation of flamboyant curves below, it is in the real tower hardly observed, while it binds it into one mass in general effect. Granting it, however, to be ugly and wrong, I like sins of the kind, for the sake of the courage it requires to commit them. In plate II. (part of a small chapel attached to the West front of the Cathedral of St. Lo), the reader will see an instance, from the same architecture, of a violation of its own principles, for the sake of a peculiar meaning. If there be any one feature which the flamboyant architect loved to decorate richly, it was the niche—it was what the capital is to the Corinthian order; yet in the case before us there is an ugly beehive put in the place of the principal niche of the arch. I am not sure if I am right in my interpretation of its meaning, but I have little doubt that two figures below, now broken away, once represented an Annunciation; and on another part of the same cathedral, I find the descent of the Spirit, encompassed by rays of light, represented very nearly in the form of the niche in question; which appears, therefore, to be intended for a representation of this effulgence, while at the same time it was made a canopy for the delicate figures below. Whether this was its meaning or not, it is remarkable as a daring departure from the common habits of the time.

XIX. Far more splendid is a license taken with the niche decoration of the portal of St. Maclou at Rouen. The subject of the tympanum bas-relief is the Last Judgment, and the sculpture of the inferno side is carried out with a degree of power whose fearful grotesqueness I can only describe as a mingling of the minds of Orcagna and Hogarth. The demons are perhaps even more awful than Orcagna's; and, in some of the expressions of debased humanity in its utmost despair, the English painter is at least equalled. Not less wild is the imagination which gives fury and fear even to the placing of the figures. An evil angel, poised on the wing, drives the condemned troops from before the Judgment seat; with his left hand he drags behind him a cloud, which is spreading like a winding-sheet over them all; but they are urged by him so furiously, that they are driven not merely to the extreme limit of that scene, which the sculptor confined elsewhere within the tympanum, but out of the tympanum and into the niches of the arch; while the flames that follow them, bent by the blast, as it seems, of the angel's wings, rush into the niches also, and burst up through their tracery, the three lowermost niches being represented as all on fire, while, instead of their usual vaulted and ribbed ceiling, there is a demon in the roof of each, with his wings folded over it, grinning down out of the black shadow.

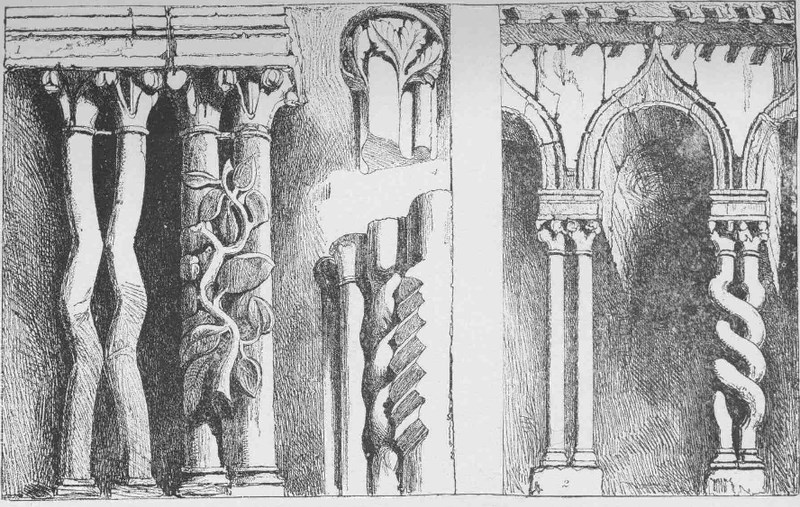

PLATE XIII.—(Page 161—Vol. V.)

Portions of an Arcade on the South Side of the Cathedral of Ferrara.

XX. I have, however, given enough instances of vitality shown in mere daring, whether wise, as surely in this last instance, or inexpedient; but, as a single example of the Vitality of Assimilation, the faculty which turns to its purposes all material that is submitted to it, I would refer the reader to the extraordinary columns of the arcade on the south side of the Cathedral of Ferrara. A single arch of it is given in Plate XIII. on the right. Four such columns forming a group, there are interposed two pairs of columns, as seen on the left of the same plate; and then come another four arches. It is a long arcade of, I suppose, not less than forty arches, perhaps of many more; and in the grace and simplicity of its stilted Byzantine curves I hardly know its equal. Its like, in fancy of column, I certainly do not know; there being hardly two correspondent, and the architect having been ready, as it seems, to adopt ideas and resemblances from any sources whatsoever. The vegetation growing up the two columns is fine, though bizarre; the distorted pillars beside it suggest images of less agreeable character; the serpentine arrangements founded on the usual Byzantine double knot are generally graceful; but I was puzzled to account for the excessively ugly type of the pillar, fig. 3, one of a group of four. It so happened, fortunately for me, that there had been a fair in Ferrara; and, when I had finished my sketch of the pillar, I had to get out of the way of some merchants of miscellaneous wares, who were removing their stall. It had been shaded by an awning supported by poles, which, in order that the covering might be raised or lowered according to the height of the sun, were composed of two separate pieces, fitted to each other by a rack, in which I beheld the prototype of my ugly pillar. It will not be thought, after what I have above said of the inexpedience of imitating anything but natural form, that I advance this architect's practice as altogether exemplary; yet the humility is instructive, which condescended to such sources for motives of thought, the boldness, which could depart so far from all established types of form, and the life and feeling, which out of an assemblage of such quaint and uncouth materials, could produce an harmonious piece of ecclesiastical architecture.

XXI. I have dwelt, however, perhaps, too long upon that form of vitality which is known almost as much by its errors as by its atonements for them. We must briefly note the operation of it, which is always right, and always necessary, upon those lesser details, where it can neither be superseded by precedents, nor repressed by proprieties.

I said, early in this essay, that hand-work might always be known from machine-work; observing, however, at the same time, that it was possible for men to turn themselves into machines, and to reduce their labor to the machine level; but so long as men work as men, putting their heart into what they do, and doing their best, it matters not how bad workmen they may be, there will be that in the handling which is above all price: it will be plainly seen that some places have been delighted in more than others—that there has been a pause, and a care about them; and then there will come careless bits, and fast bits; and here the chisel will have struck hard, and there lightly, and anon timidly; and if the man's mind as well as his heart went with his work, all this will be in the right places, and each part will set off the other; and the effect of the whole, as compared with the same design cut by a machine or a lifeless hand, will be like that of poetry well read and deeply felt to that of the same verses jangled by rote. There are many to whom the difference is imperceptible; but to those who love poetry it is everything—they had rather not hear it at all, than hear it ill read; and to those who love Architecture, the life and accent of the hand are everything. They had rather not have ornament at all, than see it ill cut—deadly cut, that is. I cannot too often repeat, it is not coarse cutting, it is not blunt cutting, that is necessarily bad; but it is cold cutting—the look of equal trouble everywhere—the smooth, diffused tranquillity of heartless pains—the regularity of a plough in a level field. The chill is more likely, indeed, to show itself in finished work than in any other—men cool and tire as they complete: and if completeness is thought to be vested in polish, and to be attainable by help of sand paper, we may as well give the work to the engine-lathe at once. But right finish is simply the full rendering of the intended impression; and high finish is the rendering of a well intended and vivid impression; and it is oftener got by rough than fine handling. I am not sure whether it is frequently enough observed that sculpture is not the mere cutting of the form of anything in stone; it is the cutting of the effect of it. Very often the true form, in the marble, would not be in the least like itself. The sculptor must paint with his chisel: half his touches are not to realize, but to put power into the form: they are touches of light and shadow; and raise a ridge, or sink a hollow, not to represent an actual ridge or hollow, but to get a line of light, or a spot of darkness. In a coarse way, this kind of execution is very marked in old French woodwork; the irises of the eyes of its chimeric monsters being cut boldly into holes, which, variously placed, and always dark, give all kinds of strange and startling expressions, averted and askance, to the fantastic countenances. Perhaps the highest examples of this kind of sculpture-painting are the works of Mino da Fiesole; their best effects being reached by strange angular, and seemingly rude, touches of the chisel. The lips of one of the children on the tombs in the church of the Badia, appear only half finished when they are seen close; yet the expression is farther carried and more ineffable, than in any piece of marble I have ever seen, especially considering its delicacy, and the softness of the child-features. In a sterner kind, that of the statues in the sacristy of St. Lorenzo equals it, and there again by incompletion. I know no example of work in which the forms are absolutely true and complete where such a result is attained; in Greek sculptures is not even attempted.

XXII. It is evident that, for architectural appliances, such masculine handling, likely as it must be to retain its effectiveness when higher finish would be injured by time, must always be the most expedient; and as it is impossible, even were it desirable that the highest finish should be given to the quantity of work which covers a large building, it will be understood how precious the intelligence must become, which renders incompletion itself a means of additional expression; and how great must be the difference, when the touches are rude and few, between those of a careless and those of a regardful mind. It is not easy to retain anything of their character in a copy; yet the reader will find one or two illustrative points in the examples, given in Plate XIV., from the bas-reliefs of the north of Rouen Cathedral. There are three square pedestals under the three main niches on each side of it, and one in the centre; each of these being on two sides decorated with five quatrefoiled panels. There are thus seventy quatrefoils in the lower ornament of the gate alone, without counting those of the outer course round it, and of the pedestals outside: each quatrefoil is filled with a bas-relief, the whole reaching to something above a man's height. A modern architect would, of course, have made all the five quatrefoils of each pedestal-side equal: not so the Mediæval. The general form being apparently a quatrefoil composed of semicircles on the sides of a square, it will be found on examination that none of the arcs are semicircles, and none of the basic figures squares. The latter are rhomboids, having their acute or obtuse angles uppermost according to their larger or smaller size; and the arcs upon their sides slide into such places as they can get in the angles of the enclosing parallelogram, leaving intervals, at each of the four angles, of various shapes, which are filled each by an animal. The size of the whole panel being thus varied, the two lowest of the five are tall, the next two short, and the uppermost a little higher than the lowest; while in the course of bas-reliefs which surrounds the gate, calling either of the two lowest (which are equal), a, and either of the next two b, and the fifth and sixth c and d, then d (the largest): c::c:a::a:b. It is wonderful how much of the grace of the whole depends on these variations.