полная версия

полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

Knox received with unusual favour this petition for his intervention, and for (to the reader) an unexpected reason: "Albeit to this hour," he said, "it hath not chanced me to speak to your lordship face to face, yet have I borne a good mind to your honour, and have been sorry in my heart of the troubles that I have heard you to be involved in. For, my lord, my grandfather, goodsire and father, have served your lordship's predecessors, and some of them have died under their standards; and this is part of the obligation of our Scottish kindness." He goes on naturally to exhort his visitor to complete repentance and "perfyte reconciliation with God;" but ends by promising his good offices for the wished-for reconciliation with man. In this mediation Knox was successful: and as the extraordinary chance would have it, it was at the Kirk of Field, doomed to such dismal association for ever with Bothwell's name, that the meeting with Arran, under the auspices of Knox—strange conjunction!—took place, and friendship was made between the two enemies. Knox made them a little oration as they embraced each other, exhorting them to "study that amitie may ensure all former offences being forgotten."

This is strange enough when one remembers the terrible tragedy which was soon to burst these walls asunder; but stranger still was to follow. The two adversaries thus reconciled came to the sermon together next day, and there was much rejoicing over the new penitent. But four days after, Arran, with a distracted countenance, followed Knox home after the preaching, and calling out "I am treacherously betrayed," burst into tears. He then narrated with many expressions of horror the cause of his distress. Bothwell had made a proposal to him to carry off the Queen and place her in Dunkeld Castle in Arran's hands (who was known to be half distraught with love of Mary), and to kill Murray, Lethington, and the others that now misguided her, so that he and Arran should rule alone. The agitation of the unfortunate young man, his wild looks, his conviction that he was himself ruined and shamed for ever, seem to have enlightened Knox at once as to the state of his mind. Arran sent letters all over the country—to his father, to the Queen, to Murray—repeating this strange tale, but soon betrayed by the endless delusions which took possession of him that his mind was entirely disordered. The story remains one of those historical puzzles which it is impossible to solve. Was there truth in it—a premature betrayal of the scheme which afterwards made Bothwell infamous? did this wild suggestion drive Arran's mind, never too strong, off the balance? or was it some strange insight of madness into the other's dark spirit? These are questions which no one will ever be able to answer. It seems to have caused much perturbation in the Court and its surroundings for the moment, but is not, strangely enough, ever referred to when events quicken and Bothwell shows himself as he was in the madman's dream.

The chief practical question on which Knox's mind and his vigorous pen were engaged during this early period of Mary's reign was the all-important question to the country and Church of the provision for the maintenance of ministers, for education, and for the poor—the revenues, in short, of the newly-established Church, these three objects being conjoined together as belonging to the spiritual dominion. The proposal made in the Book of Discipline, ratified and confirmed by the subscription of the lords, was that the tithes and other revenues of the old Church, apart from all the tyrannical additions which had ground the poor (the Uppermost Cloth, Corpse present, Pasch offerings, etc.), should be given over to the Congregation for the combined uses above described. This in principle had been conceded, though in practice it was extremely hard to extract those revenues from the strong secular hands into which in many cases they had fallen, and which had not even ceased to exact the Corpse present, etc. The Reformers had strongly urged the necessity of having the Book of Discipline ratified by the Queen on her arrival; but this suggestion had been set aside even by the severest of the lords as out of place for the moment. To such enlightened critics as Lethington the whole book was a devout imagination, a dream of theorists never to be realised. The Church, however, with Knox at her head, was bent upon securing this indispensable provision, though it may well be supposed that now, with not only the commendators and pensioners but the bishops themselves and other ecclesiastical functionaries, inspirited and encouraged by the Queen's favour, and hoping that the good old times might yet come back, it was more difficult than ever to get a hearing for their claim. And great as was the importance of a matter involving the very existence of the new ecclesiastical economy, it was, even in the opinion of the wisest, scarcely so exciting as the mass in the Queen's chapel, against which the ministers preached, and every careful burgher shook his head; although the lords who came within the circle of the Court were greatly troubled, knowing not how to take her religious observances from the Queen, they who had just at the cost of years of conflict gained freedom for their own. On one occasion when a party of those who had so toiled and struggled together during all the troubled past were met in the house of one of the clerk registers, the question was discussed between them whether subjects might interfere to put down the idolatry of their prince—when all the nobles took one side, and John Knox, his colleagues, and a humble official or two were all that stood on the other. As a manner of reconciling the conflicting opinions Knox was commissioned to put the question to the Church of Geneva, and to ask what in the circumstances described the Church there would recommend to be done. But the question was never put, being transferred to Lethington's hands, then back again to those of Knox, perhaps a mere expedient to still an unprofitable discussion rather than a serious proposal.

While these questions were being hotly and angrily discussed on all sides, the preachers and their party growing more and more pertinacious, the lords impatient, angry, chafed and fretted beyond bearing by the ever-recurring question in which they were no doubt conscious, with an additional prick of irritation, that they were abandoning their own side, Mary, still fearing no evil, very conciliatory to all about her, and entirely convinced no doubt of winning the day, went lightly upon her way, hunting, hawking, riding, making long journeys about the kingdom, enjoying a life which, if more sombre and poor outwardly, was far more original, unusual, and diverting than the luxurious life of the French Court under the shadow of a malign and powerful mother-in-law. It did not seem perhaps of great importance to her that the preachers should breathe anathemas against every one who tolerated the mass in her private chapel, or that the lords and their most brilliant spokesman, her secretary Lethington, should threaten to stop the Assemblies of the Church in retaliation. The war of letters, addresses, proclamations, which arose once more between the contending parties is wonderful in an age which might have been thought more given to the sword than the pen. But it at last became evident that something must be done in one way or the other to stop the mouth of the indomitable Knox, with whom were all the central mass of the people, not high enough to be moved by the influences of the Court, not low enough to fluctuate with every fickle popular fancy. Finally it was decided that the Queen should issue a decree for a valuation of all ecclesiastical possessions in Scotland—a necessary preliminary measure, but turned into foolishness by the stipulation that these possessions should be divided into three parts, two to remain with the present possessors, while the remaining portion should be divided between the ministers and herself. This proposed arrangement, with which naturally every one was discontented, called forth a flight of furious jests. "Good-morrow, my lords of the Twa-pairts," said Huntly to the array, spiritual and secular, who were to retain the lion's share; while, on the other hand, Knox in the pulpit denounced the division. "I see twa parts partly given to the Devil, and the third maun be divided between God and the Devil," he cried. "Bear witness to me that this day I say it: ere it be long the Devil shall have three parts of the third; and judge you then what God's portion shall be."—"The Queen will not have enough for a pair of shoes at the year's end after the ministers are sustained," said Lethington; and Knox records the "dicton or proverb" which arose, as such sayings do, out of the crowd, in respect to the official, the Comptroller, who had charge of this hated partition—"The Laird of Pitarrow," cried the popular voice, "was ane earnest professor of Christ; but the meikle Deil receive the Controller."

About this time Knox had the opportunity he had long coveted of a public disputation upon the mass; but it was held far from the centre of affairs, at the little town of Maybole in Ayrshire, where Quentin Kennedy of the house of Cassilis, Abbot of Crossraguel (upon whose death George Buchanan secured his appointment as pensioner), announced himself as ready to meet all comers on this subject. Knox would seem to have attached little importance to it, as he does no more than mention it in his History; but a full report exists of the controversy, which has much more the air of a personal wrangle than of a grave and solemn discussion. "Ye said," cries the abbot, "ye did abhor all chiding and railing, but nature passes nurture with you."—"I will neither change nature nor nurture with you for all the profits of Crossraguel," says the preacher. These amenities belonged to the period. But the arguments seem singularly feeble on both sides. The plea of the abbot rested upon the statement in the Old Testament that Melchizedec offered bread and wine to God. On the other side a simple denial of this, and reassertion that the mass is an idolatrous rite, seems to have sufficed for Knox. It is almost impossible to believe that they did not say something better worth remembering on both sides. What they seem to have done is to have completely wearied out their auditors, who sat for three days to listen to the altercation, and then broke up in disgust. It is curious that Knox, so unanswerable in personal controversy, should have been so little effectual (so far as we can judge) in this. There is a discussion in another part of the History upon baptism, in which he denounces the Romish ceremonies attached to that rite as unscriptural, precisely as if the Apostles had described in full the method to be employed.

It is probable that it was the progress of Knox through the West on this occasion which encouraged and stimulated the gentlemen of that district, always the most strenuous of Reformers, the descendants of the Lollards, the forefathers of the Whigs, to take the law into their own hands in respect to those wandering and dispossessed priests who, encouraged by the example and support of the Queen, began to appear here and there in half-ruined chapels or parish churches to set up a furtive altar and say a mass, at peril if not of their lives at least of their liberty. When Knox returned to Edinburgh the Queen was at Lochleven, not then a prison but a cheerful seclusion, with the air blowing fresh from the pleasant loch, and the plains of Kinross and Fife all broad and peaceful before her, for the open-air exercises in which she delighted. She sent for Knox to this retirement and threw herself upon his aid and charity to stop these proceedings. It was not the first time they had met. Two previous interviews had taken place, in the first of which Mary gaily encountered the Stern author of the "Blast" upon that general subject, and won from him a blessing at the end of the brief duel in which there was no bitterness. The second had been on the occasion when Knox, in the pulpit, objected to the dancing and festivities of Holyrood; but still was of no very formidable character. I cannot doubt that Mary found something very humorous and original in the obstinate and dauntless prophet whom she desired to come to her and tell her privately when he objected to her conduct, and not to make it the subject of his sermons—a very natural and apparently gracious request: from which Knox excused himself, however, as having no time to come to her chamber door and whisper in her ear. "I cannot tell even what other men will judge of me," he said, "that at this time of day am absent from my buke, and waiting upon the Court."—"Ye will not always be at your buke," said the Queen. And it was on this second interview that as he left the presence with a composed countenance some foolish courtier remarked of Knox that he was not afraid, and elicited the answer, noble and dignified if a little truculent and exaggerated after an encounter not at all solemn, "Why should the pleasing face of a gentlewoman afray me? I have looked in the faces of many angry men and yet have not been affrayed above measour"—a most characteristic reply.

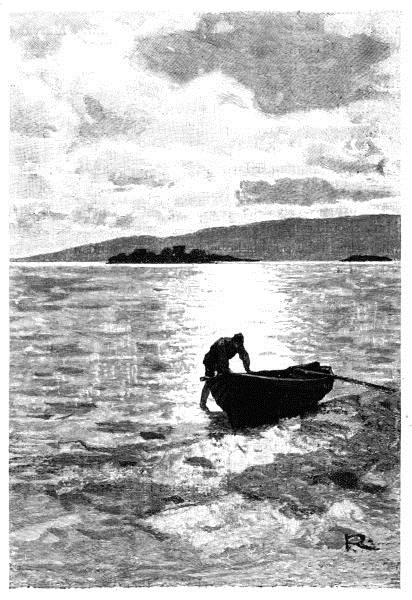

LOCHLEVEN

Mary, however, had another purpose when she sent for Knox to Lochleven, to help her in a strait. "She travailed with him earnestly two hours before her supper that he would be the instrument to persuade the people and principally the gentlemen of the West not to put hands to punish (the priests) any more for the using of themselves in their religion as pleased them." The Reformer perceiving her intention assured her that if she would herself punish these malefactors, no one would interfere; but he was immovable to any argument founded on the patent fact that he and his party had lately called that the persecution of God's saints which now they termed the execution of the law. Mary did not enter into this controversy; she kept to her point—the vindication of her own authority. "Will you," she said, "allow that they should take my sword in their hand?" a question to which Knox had his answer plain and very full, that the sword was God's, and that Jezebel's priests were not spared by Elijah nor Agag by Samuel because the royal authority was in their favour. It would be difficult to conceive anything more exasperating than such an immovable front of dogmatism; and it was a wonder of self-control that Mary should only have shown herself "somewhat offended" when she broke off this hopeless argument, and withdrew to supper. The Reformer thought he was dismissed; but before sunrise next morning two several messengers came to his chamber to bid him speak with the Queen before he took his departure. It was a May morning, and no doubt there was soon much cheerful commotion in the air, boats pushed forward to the landing steps with all that tinkle of water and din and jar of the oars which is so pleasant to those who love the lochs and streams—for Mary was bound upon a hawking expedition, and the preacher's second audience was to be upon the mainland. The Queen must have been up betimes while the mists still lay on the soft Lomonds, and the pearly grey of the northern skies had scarcely turned to the glory of the day: and probably the preacher who was growing old was little disposed to join the gay party whose young voices and laughter he could hear in his chamber, where he lay "before the sun"—setting out for the farther shore with a day's pleasure before them. It would be interesting to penetrate what were his thoughts as he was rowed across the loch at a more reasonable hour, when the sunshine shone on every ripple of the water, and the green hills lay basking in the light. Did he look with jealous eyes, and wonder whether the grey walls among the trees on St. Serf's isle were giving shelter to some idolatrous priest? or was his heart invaded by the beauty of the morning, the heavenly quiet, the murmur of soft sound? His mind was heavy we know with cares for the Church, fears for the stability of the Reformation itself, forebodings of punishment and cursings more habitual to his thoughts, and perhaps more congenial to the time, than prosperity and blessing. It might be even that a faint apprehension (not fear, for in his own person Knox had little occasion for fear even had he been of a timorous nature) of further trouble with the Queen overclouded his aspect: and if he caught a glimpse of the ladies and their cavaliers on the mainland, the joyous cavalcade would rouse no sympathetic pleasure, so sure was he that their frolics and youthful pleasure were leading to misery and doom—in which, alas! he was too sooth a prophet.

But when Knox met the Queen's Majestie "be-west Kinross," Mary all bright with exercise and pleasure had forgotten, or else had no mind to remember, the offence of the previous night. She began to talk to him of ordinary matters, of Ruthven who had (save the mark!)—dark Ruthven not many years removed from that dreadful scene in the closet at Holyrood—offered her a ring, and other such lively trifles. She then turned to more serious discourse, warning Knox against Alexander Gordon, titular Bishop of Athens, "who was most familiar with the said John in his house and at his table," and whose professions of faith seemed so genuine that he was about to be made Superintendent of Dumfries. "If you knew him as well as I do, you would never promote him to that office nor to any other within your Kirk," she said. "Thereintil was not the Queen deceived," says Knox, though without any acknowledgment of the service she did the Church: for on her hint he caused further inquiries to be made, and foiled the Bishop. Again, as so often, a picture arises before our eyes most significant and full of interest. Mary upon her horse, perhaps pausing now and then to glance afar into the wide space, where her hawk hung suspended a dark speck in the blue, or whirled and circled downward to strike its prey, while the preacher on his hackney paused reluctant, often essaying to take his leave, retained always by a new subject. Suddenly she broached another and more private matter, turning aside from the attendants to tell Knox of the new troubles which had broken out in the house of Argyle between the Earl and his wife, who was Mary's illegitimate sister. The Reformer had already settled a quarrel between this pair, and the Queen begged him to interfere again, to write to Argyle and smooth the matter over if possible. Then, the time having now arrived when she must dismiss him, the field waiting for her and the sport suspended, Mary turned again for a parting word.

"And now," said she, "as touching our reasoning yesternight I promise to do as ye required. I sall cause summon the offenders, and ye shall know that I shall minister justice."

"I am assured then," said he, "that ye shall please God and enjoy rest and prosperity within your realm; which to your Majesty is more profitable than all the Pope's power can be."

We have heard enough and to spare about Mary's tears and the severity of Knox—here is a scene in which for once there is no severity, but everything cheerful, radiant, and full of hope. Was there in all Christendom a more hopeful princess, more gifted, more understanding, more wise? for it was not only that she had the heart to take (or seem to take) in a very hard matter the advice of the exasperating Reformer, entirely inaccessible to reason on that point at least as he was—but to give it, and that in a matter of real use to himself and his party. Was it all dissembling as Knox believed? or was there any possibility of public service and national advantage, and as happy and prosperous a life as was possible to a queen, before her when she turned smiling upon the strand and waved her hand to him as he rode away? Who can tell? That little tower of Lochleven, that dark water between its pastoral hills, had soon so different a tale to tell.

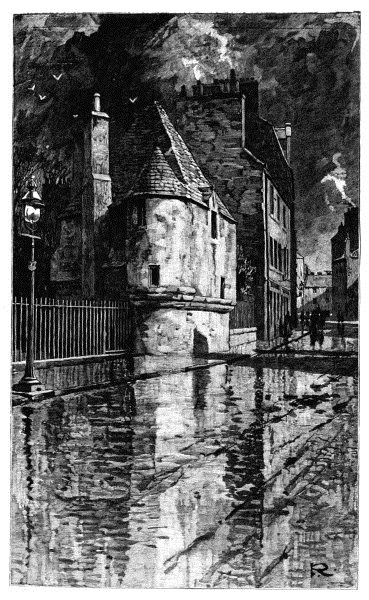

QUEEN MARY'S BATH

Had Mary deserted her faith as it would have been such admirable policy to do; had she said, like the great Henry, that Scotland was well worth a mass or the sacrifice of a mass; had she turned round and persecuted the priests of her own Church as she now was about, for their safety and with a subterfuge excusable if ever subterfuge was, to pretend to do—would posterity have thought the better of her? Certainly it would not; but Knox would, and her path would have been a thousand times more clear. Only it has to be said at the end of all, that religion had little part in the woes of Mary. Had there been no Darnley or Bothwell in her path, had it been in her nature to take that wise resolution of Elizabeth's, wise for every woman who has great duties and position of her own, how wonderfully everything might have been changed! Such reflections, however, are very futile, though they are strangely fascinating.

Knox wrote to Argyle immediately after with that plain speaking in which he delighted, and made the Earl very angry. It might well have been part of Mary's "craft," knowing that he was sure to do this, to embroil him with her brother-in-law. And she prosecuted her bishops to save them from the Westland lords, and imprisoned them gently to keep them out of harm's way. Neither of these acts was very successful, and it would seem that the mollifying impression that had been made upon Knox soon died away; for when the Queen opened the next Parliament he speaks of her splendour and that of her train in words more like those of a peevish scold than of a prophet and statesman. "All things mislyking the preachers," he says with candour, "they spoke boldly against the tarjatting of their tails, and against the rest of their vanity, which they affirmed should provoke God's vengeance not only against those foolish women, but against the whole Realm." God's vengeance was freely dealt out on all hands against those who disagreed with the speakers; but the silken trains that swept the ground, the wonderful clear starching of the delicate ruffs, the embroidered work of pearls and gems which the fashion of the time demanded, were but slight causes to draw forth the flaming sword. And that Parliament was very unsatisfactory to Knox and his friends; they tried to bring in a sumptuary law; they endeavoured to have immorality recognised as crime, and subjected to penalties as such; and above all, they attempted to obtain the ratification of various matters of discipline upon which Knox so pressed that the quarrel rose high between him and Murray, and there ensued a breach and lasting coolness—Murray being as unwilling to press Queen Mary into measures she disliked, as Knox was determined that only by doing so was God's vengeance to be averted. When the Parliament was over the preacher made his usual commentary upon it in the pulpit; warning the lords what miseries were sure to follow from their carelessness, and discussing the chances of the Queen's marriage with much freedom and boldness. Once more, though with more reason, was God's vengeance invoked. "This, my lords, will I say (note the day and bear witness after), whensoever the Nobilities of Scotland, professing the Lord Jesus, consents that ane infidel (and all Papists are infidels) shall be head to your Soverane, ye do so far as in ye lieth to banish Christ Jesus from this realm." This sermon was reported to Mary with aggravations, though it was offensive enough without any aggravations; and once more he was summoned to the presence. The Queen was "in a vehement furie," deeply offended, and in her nervous exasperation unable to refrain from tears, a penalty of weakness which is one of the most painful disabilities of women. "What have ye to do with my marriage?" she cried again and again, with that outburst which Knox describes somewhat brutally as "owling." His own bearing was manly though dogged. Naturally he did not withdraw an inch, but repeated to her the scope of his sermon with amplifications, while the gentler Erskine of Dun who accompanied him endeavoured to soothe the paroxysm of exasperated impatience and pain which Mary could not subdue, and for which no doubt she scorned herself.

"The said John stood still without any alteration of countenance, while that the Queen gave place to her inordinate passion; and in the end he said, 'Madam, in God's presence I speak, I never delighted in the weeping of any of God's creatures; yea, I can scarcely well abide the tears of my own boys whom my own hand corrects, much less can I rejoice in your Majestie's weeping. But seeing that I have offered you no just occasion to be offended, but have spoken the truth as my vocation craves of me, I must sustain, albeit unwillingly, your Majesty's tears rather than I dare hurt my conscience or betray my Commonwealth through my silence.'"