полная версия

полная версияRoyal Edinburgh: Her Saints, Kings, Prophets and Poets

There is a curious story told of how Lord Lindsay of the Byres, a fierce and grim baron of Fife, presented on the very eve of the battle "a great grey courser" to the King, assuring him that were he ever in extremity that horse would carry him, "either to fly or to follow," better than any horse in Scotland, "if well sitten"—a present which James accepted, and which comes in as part of the paraphernalia of fate. On the morning of the day of battle the King mounted this horse, and "rade to ane hill head to see the manner of the cuming" of his enemies against him. He saw the host defiling "in three battells," with six thousand men in each, their spears shining, their banners waving, Homes and Hepburns in the front, with Merse and Teviotdale and all the forces of the Border, and the men of Lothian in the rear: while in the main body rose the ensigns of all the great lords who had already beaten and humbled him—Bell-the-Cat and the other barons who had hanged his friends before his eyes—but now bearing his own royal standard, with his son among them, the bitterest thought of all. James sat upon his fleet horse, presented to him the night before with such an ominous recommendation, and saw his enemies bearing down upon him—his enemies and his son. "Then," says the chronicler, "he remembered the words which the witch had spoken to him many days before, that he should be suddenly destroyed and put down by the nearest of his kin." For this he had allowed the murder of young Mar and driven Alexander of Albany into exile; but who can wonder if in his stricken soul he now perceived or imagined that no man can cheat the Fates? His own son, his boy! Some nobler poignancy of anguish than the mere sick despair and panic of the coward must surely have been in his mind as he realised this last and crowning horror. The profound moral discouragement of a man caught in the toils, and for whom no escape was possible; the sickening sense of betrayal; the wide country before him, in which there might still be found some peaceful refuge far from these distractions and contradictions of men; the whirl of the dreadful yet beautiful sight, companies marching and ever marching, spears and helmets shining, banners waving, and all against him—a man who had never any pleasure in the pomp and circumstance of war. Who can wonder as these hurrying thoughts overwhelmed his mind, and the fleet courser pawed the turf, and the wild sweet air blew free in his face, inviting him to escape, to flee, to find somewhere comfort and peace—that such a man should have yielded to the mad impulse, and in an access of despair, longing for the wings of a dove that he might flee away and be at rest, have turned from the rising tumult and fled?

Of all the ironies of Fate there could be none more bitter than that which drove the hapless fugitive, in growing consciousness of shame, like a straw before the wind, across the famous field of Bannockburn. What an association to be connected with that victorious name! He had aimed at Stirling, but wild with despair and panic and misery missed the way. As the grey courser entered the village of Bannockburn at full flight a woman drawing water let fall her "pig" or earthen pot in affright, and startled the horse; and the King "being evill sitten" (having a bad seat) fell from his saddle before the door of the mill. The sight of this strange cavalier in his splendid armour, covered with foam and dust, borne to the earth like a log by the weight of his armour, appalled the simple people, who dragged him inside the mill and covered him where he lay with some rough horsecloth, not knowing what to do. When he had come to himself James implored the wondering people to fetch him a priest before he died. "Who are you?" they asked, standing over him. What a world of time had passed in that wild ride! how many ages since the dying fugitive lying on the dusty floor and covered with the miller's rug was James Stewart, at the head of a gallant army! "This morning," he said, with a bitter comprehension of all that had passed since then, "I was your King." The miller's wife ran forth to her door calling for a priest, and some one who was passing by answered her call; but whether he was really a priest, or only one of the stragglers of the rebel army, seems uncertain. He came into the mill, hearing no doubt the cries of the astonished couple that it was the King, and kneeling down recognised the fallen monarch; but instead of hearing his confession, drew a knife and stabbed him three or four times in the breast. Thus miserably ended James Stewart, the third of the name.

Of all the tragical conclusions to which his family had come this was the most deplorable, as his life had been the least satisfactory. Whether there was more than weakness to be alleged against him it is now impossible to tell; and whether his favourite companions and occupations proved a spirit touched to finer issues than those about him, or showed only, as his barons thought, a preference for low company and paltry pursuits of peace. But howsoever his patronage of the arts, the buildings he has left to Scotland, or the tradition of the music and gentle pleasures which he loved, may justify him to the reader, it is at least clear that his stewardry of his kingdom was a miserable failure, and his life a loss and harm to his country. Instead of promoting the much-interrupted progress of her development, so far as his individual influence went, he arrested and hindered it. And, difficult as the position of affairs had been when he succeeded at seven years old to his father's uncompleted labours, the situation which he left behind him, the country torn in two, one half of his subjects in arms against the other, his son's name opposed to his own, and every national benefit postponed to the settlement of this quarrel, was ten times more difficult and terrible. He was the first of his name whose influence was all unfavourable to the progress of the nation, not only by evil fortune, but by the disasters of a mind not sufficient for the weight and burden of his time. He thus died ignominiously, in the month of June 1488, having reigned twenty-eight years and lived thirty-five—a short lifetime for so much trouble and general misfortune.

ARMS OF JAMES IV OF SCOTLAND

(From King's College Chapel, Old Aberdeen)

CHAPTER IV

JAMES IV: THE KNIGHT-ERRANT

The graver records of the nation pause at the point to which we have arrived. The tale leaves both battlefield and council chamber, though there is an inevitable something of both in the chronicle as there is something of daily bread in the most festive day. But it is not with these grave details that the historian occupies himself. The most serious page takes a glow from the story it has to tell, the weighty matters of national life and development stand aside, and it is a knight of romance who stands forth to occupy the field. The story of James, the fourth of the name, is one of those passages of veritable history in which there is scarcely anything that might not be borrowed from a tale of chivalry. It is pure romance from beginning to end.

Of the character and personality of the boy whose education was carried on under strict surveillance at Stirling we know nothing whatever, until he suddenly appears before us in the enemy's camp, whether with his own consent or not, or how much, if with his own consent, with any knowledge of what he was about, it is difficult to tell. His mother had died while he was still a child, and probably for the last few years of his much disturbed life James III had but little attention to spare for his son. If there is any truth in a curious story told by Pitscottie of a search on board Sir Andrew Wood's ship for the murdered King, while yet the fact of his death was unknown, and the Prince's wistful address to the great sailor, "Sir, are ye my father?" we might suppose that the boy had been banished altogether from his father's presence. But perhaps this is too slender a foundation to build upon. There can be no doubt, however, that after the battle, little honourable to either side, and lost by the King's party almost before begun, from which he fled in a panic so ignominious and fatal, there was a moment of great perplexity and dismay, when King James's fate remained a mystery, and the rebel nobles with the boy-prince among them knew not what to do or to say, in the doubt whether he was dead or alive, whether he might not reappear at any moment with a host from the Highlands or from France, or even England, at his back. When they had fully realised their unsatisfactory victory they marched to Edinburgh, with the Prince always among them and a chill horror about them, unaware what way to look for news of the King. The rush of the people to watch their return with their drooping banners and faces full of consternation, and wonder at the unaccustomed sight of the young Prince which yet was not exciting enough to counterbalance the anxiety, the wonder, the perpetual question what had become of the King—must have been as a menace the more to the perplexed leaders, who knew that a fierce mob might surge up into warfare at any moment, or a rally from the castle cut off their discouraged and weary troops. Where was the King? Had he perhaps got before them to Edinburgh? was he there on that height, misty with smoke and sunshine, turning against them the great gun, which had been forged for use against the Douglas: or ready to appear from over the Firth terrible with a new army; or in the ships, most likely of all, with the great admiral who lay there watching, ready to carry off a royal fugitive or bring back strange allies to revenge the scorn that had been done to the King? The lords decided to take their dispirited and broken array to Leith instead of going to Holyrood, and there collected together to hold a council of war. Among the confused reports brought to them of what one man and another had seen or heard was one, more likely than the rest, of boats which had been seen to steal down Forth and make for the Yellow Carvel lying in the estuary, with apparently wounded men on board. They sent accordingly to summon Sir Andrew Wood to their presence. The sailor probably cared nothing about politics any further than that he held for the King—and furious with the Lords who had withstood his Majesty declined to come unless hostages were sent for his safety. When this was accorded, the old sea-lion, the first admiral of Scotland, came gruffly from his ships to answer their questions. Whether there was any resemblance between the two men, as he stood with his cloak wrapped round him defiant before the rebel lords, or if the Prince had, as is possible, been so long absent from his father that the vague outline of a man enveloped and muffled deceived him, it is impossible to say. But there is a tone of penetrating reality in the "Sir, are ye my father?" of the troubled boy, perhaps only then aroused to a full comprehension of his position and the sense that he was himself guiltily involved in the proceedings which had brought some mysterious and unknown fate upon the King. It is difficult to see why, accepting from Pitscottie all the rest of this affecting narrative, the modern historian should cut out this as unworthy of belief, "Who answered," continues the chronicler, "with tears falling from his eyes,"

"'Sir, I am not your father, but I was a servand to your father, and sall be to his authoritie till I die, and ane enemy to them that was the occasion of his doon-putting.' The lords inquired of Captain Wood if he knew of the King or where he was. He answered he knew nothing of the King nor where he was. Then they speired what they were that came out of the field and passed into his ships. He answered: 'It was I and my brother, who were ready to have waired our lives with the King in his defence.' Then they said, 'He is not in your ships?' who answered again, 'He is not in my ship, but would to God he were in my ship safelie, I should defend him and keep him skaithless frae all the treasonable creatures who has murdered him, for I think to see the day when they shall be hanged and quartered for their demerites.'"

The lords would fain have silenced this rude sailor, but having given hostages for his safe return were obliged to let him go. There could not be a more vivid picture of their perplexity and trouble. They proceeded to Edinburgh after this rebuff, coming in, we may well believe, with little sound of trumpet or sign of welcome, and with many a threatening countenance among the crowds that gazed wistfully upon the boy in their midst, who, if the King were really dead, was the King—another James. There might be old men about watching from the foot of the Canongate the silent cortege trooping along the valley to Holyrood—men who remembered with all the force of boyish recollection how the assassins of James I. had been dragged and tormented through Edinburgh streets, and might wonder and whisper inquiries to their sons whether such a horrible sight might be coming again, and what part that pale boy had in the dreadful deed? It was but fifty years since that catastrophe, and already two long minorities had paralysed the progress of Scotland. How the crowding people must have eyed him, as he rode along, the slim stripling, so young, so helpless, in the midst of all these bearded men! What part did he have in it? Was his father done to death by his orders? Was he consenting at least to what was done? Was he aware of all that was to follow that hurried ride with the lords, into which he had been beguiled or persuaded? James III had to some degree favoured Edinburgh, where, notwithstanding his long captivity in the Castle, he had found defenders and friends. And there must have been many in the crowd who took part with the unfortunate monarch, so mysteriously gone out of their midst, and who looked with horror upon the boy who had something at least to do with the ruin and death of his father. It was a sombre entry upon the future dwelling to which this young James was to bring so much splendour and rejoicing.

How these doubts were cleared up and certainty attained we have no sure way of knowing. Pitscottie's story is that when the false priest murdered the King, he took up the body on his back and carried it away, "but no man knew what he did with him or where he buried him." Other authorities speak of a funeral service in the Abbey of Cambuskenneth on the banks of the Forth—a great religious establishment, of which one dark grey tower alone remains upon the green meadows by the winding river; and there is mention afterwards of a bloody shirt carried about on the point of a lance to excite the indignant Northmen to rebellion. But notwithstanding these facts no one ventures to say that James's body was found or buried. Masses for the dead were sung, and every religious honour paid; but so far as anything is told us, these rites might have been performed around an empty bier. At last however, in some way, a dolorous certainty, which must by many have been felt as a relief, was attained, and the young King was crowned in Edinburgh in the summer of 1488, some weeks after his father's death. At the same time a Parliament was called, and the Castle of Edinburgh, which all this time seems to have kept its gates closed and rendered no submission, was summoned by the herald to yield, "which was obediently done at the King's command," says the chronicle. There was evidently no thought of rebellion or of resisting the lawful sovereign, so soon as it was certain which he was. The procession of the herald, perhaps the Lord Lyon himself, with all his pursuivants, up the long street to sound the trumpets outside the castle gates and demand submission, must have brightened the waiting and wondering city with the certainty of the new reign. But the bravery and fine colours of such a procession, though made doubly effective by the background of noble houses and all the lofty gables and great churches in the crowded picturesque centre at the foot of the Castle Hill, were not then as now strange to the "grey metropolis of the North." No country in Christendom would seem to have so changed under the influence of the Reformation as Scotland. The absence of pageant and ceremonial, the discouragement of display, the suppression of the picturesque in action, in the midst of one of the most picturesque scenes in the world, are all of modern growth. In the fifteenth century, and especially in the reign that was now begun, the town ran over with bright colour and splendid spectacle. When the lists were formed upon the breezy platform, overlooking the fair plains of Lothian, the great Firth, and the surrounding circle of hills, at the castle gate—how brilliant must have been both scene and setting, the living picture and the wonderful frame, and how every window would be crowded to see the hundred little processions of knights to the jousts and ladies to the tribunes, and the King and Queen riding with all their fine attendants "up the toun" all the way from Holyrood! Nor would the curiosity be much less when, coming in from the country, with every kind of quaint surrounding, the great nobles with their glittering retinue, the lairds each with a little posse of stout men-at-arms, as many as he could muster, the burgesses from the towns, the clergy from all the great centres of the Church, on mules and soft-pacing palfreys, would gather for the meetings of Parliament. It scarcely wanted a knight-errant like the fourth James, with his chivalrous tastes and devices, to fill the noble town with brightness, for all these fine sights were familiar to Edinburgh. But the brightest day was now to come.

OLD HOUSE IN LAWNMARKET

The Parliament which assembled in all the emotion of that curious crisis, while still the wonder and dismay of the King's tragic disappearance were in the air, was a strange one. It was evidently convened with the intention of shielding the party which had taken arms against James III, while making a cunning attempt to throw the blame on those who had stood by him: these natural sentiments being combined with the determination, most expedient in the circumstances, to reconcile all by punishing none. The young King and the power now exercised in his name were in the hands of the lords who had headed the rebellion, Angus, Home, Bothwell, and the rest; and while their own safety was naturally their first consideration, they had evidently no desire to stir up troublesome questions even for the fierce joy of condemning their opponents. At one or other of the early Parliaments in this reign, either that first held by way of smoothing over matters and preparing such an account of all that had happened as might be promulgated by foreign ambassadors to their respective Courts—or one which followed the easy settlement of an attempt at rebellion already referred to, when the Lord of Forbes carried a bloody shirt, supposed to be that of King James, through the streets of Aberdeen, and raised a quickly-quelled insurrection—there occurs the trial of Sir David Lindsay, one of the most quaint narratives of a cause célèbre ever written. The chronicler, whom we may quote at some length—and whose living and graphic narrative none even of those orthodox historians who pretend to hold lightly the ever-delightful Pitscottie, upon whom at the same time they rely as their chief authority, attempt to question in this case—was himself a Lindsay, and specially concerned for the honour of his name. The defendant was Lindsay of the Byres, one of the chief of James III's supporters, he who had given the King that ominous gift of a fleet courser on the eve of the battle. When he appeared at the bar of the house so to speak—before Parliament—the following "dittay" or indictment was made against him:—

"Lord David Lindsay of the Byres compeir for the cruel coming against the King at Bannokburne with his father, and in giving him counsall to have devored his sone, the King's grace, here present: and to that effect gave him ane sword and ane hors to fortify him against his sone: what is your answer heirunto?"

A more curious reversal of the facts of the case could not be, and the idea that James the actual monarch could be a rebel against his own son, then simply the heir to the crown, is bewildering in its grave defiance of all reason. There is not much wonder that Lindsay, "ane rasch man, and of rud language, albeit he was stout and hardy in the field and exercised in war," burst forth upon the assembled knights and lords, upbraiding them with bringing the Prince into their murderous designs against the King. The effect of his speech on the assembly would seem to have been considerable, and it is very apparent that the party in power had no desire to make any fight, for the Chancellor anxiously excused Lindsay to the King as "ane man of the old world, that cannot answer formallie nor get speech reverentlie in your Grace's presence." This roused the brother of the culprit, a certain Mr. Patrick Lindsay, otherwise described as a Churchman, who was by no means content to see the head of his house thus described, nor yet that Lord Lindsay should come "in the King's will," thus accepting forfeiture or any other penalties that might be pronounced against him. Accordingly he interfered in the following remarkable way:—

"To that effect he stamped on his brother's foot to latt him understand that he was not content with the decree which the Chancellour proponed to him. But this stamp of Mr. Patrick's was so heavy upon his brother's foot, who had ane sair toe which was painful to him, wherefore he looked to him and said, 'Ye were over pert to stampe upon my foot; were you out of the King's presence I would overtake you upon the mouth.' Mr. Patrick, hearing the vain words of his brother, pled on his knees before the King and the Justice, and made his petition to them in this manner: 'Sir, if it will please your Grace and your honorabill counsall, I desire of your Grace, for His cause that is Judge of all, that your Grace will give me leave this day to speak for my brother, for I see there is no man of law that dare speak for him for fear of your Grace; and although he and I has not been at ane this mony yeires, yet my heart may not suffer me to see the native house whereof I am descended to perish!' So the King and the Justice gave him leave to speak for his brother. Then the said Mr. Patrick raise off his knees, and was very blythe that he had obtained that license with the King's favour. So he began very reverentlie to speak in this manner, saying to the whole lords of Parliament, and to the rest of them that were accusers of his brother at that time, with the rest of the lords that were in the summons of forfaltrie, according to their dittay, saying: 'I beseech you all, my lords, that be here present, for His sake that will give sentence and judgment on us all at the last day, that ye will remember now instantly is your time … therefore now do all ye would be done to in the administration of justice to your neighbours and brethren, who are accused of their lives and heritages this day, whose judgment stands in your hands. Therefore beware in time, and open not the door that ye may not steik.' Be this Mr. Patrick had ended his speeches, the Chancellour bid him say something in defence of his brother, and to answer to the points of the summons made and raised upon his brother and the rest of the lords and barons. Then Mr. Patrick answered again and said: 'If it please the King's grace, and your honours that are here present, I say the King should not sit in judgment against his lords and barons, because he has made his oath of fidelity when he received the crown of Scotland that he should not come in judgment against his lords and barons in no action where he is partie himself. But here His Grace is both partie, and was at the committing of the crime himself, therefore he ought not, neither by the law of God nor of man, to sit in judgment at this time; wherefore we desire him, in the name of God, to rise and depart out of judgment, till the matter be further discussed conform to justice.'"

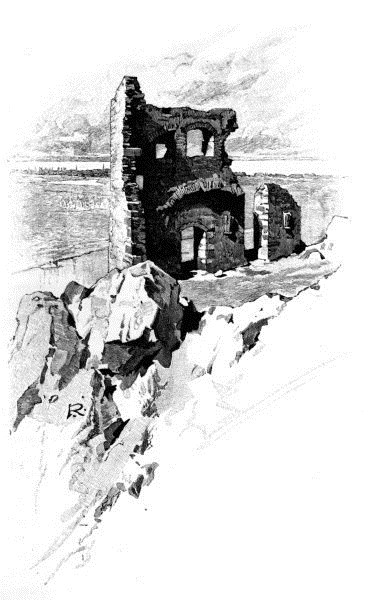

ST. ANTHONY'S CHAPEL

This bold request apparently commended itself to the Parliament, for we hear that the Chancellor and lords considered it reasonable, and the King was accordingly desired "to rise up and pass into the inner tolbooth, which," adds Pitscottie, "was very unpleasant to him for the time, being ane young prince sittand upon his royall seat to be raised by his subjects." Mr. Patrick so pressed his advantage after this strange incident, and the argument of the young King's presence and complicity in all that had happened was so unanswerable, added to some inaccuracy in the indictment, of which the keen priest made the most, that the summons was withdrawn, and Lindsay along with all the other barons of his party would seem to have shared in the general amnesty, as probably was the intention of all parties from the beginning. For the victors, who were victors by a chance, were not powerful enough to carry matters with a high hand, and their opponents, though overcome, were too strong to be despised. It was better for all to gather round the new King, who had no evil antecedents nor anything to prevent a new beginning of the most hopeful kind. The scene ends with characteristic liveliness. "The lord David Lindsay was so blyth at his brother's sayings that he burst forth saying to him, 'Verrilie, brother, ye have fine pyet words. I should not have trowed, by St. Amarie, that you had sic words'"—an amusing tribute of half-scornful gratitude from the soldier to the Churchman whose pyet or magpie words were so wonderfully efficacious, yet so despicable in themselves, to change the fate of a gentleman! It is grievous to find that the King was so displeased at Mr. Patrick and his boldness that he sent him off to the Ross of Bute, and kept him imprisoned in that solitary yet beautiful region for a whole year.