полная версия

полная версияLectures on Architecture and Painting, Delivered at Edinburgh in November 1853

Fig. 10.

Fig. 9.

PLATE VI.

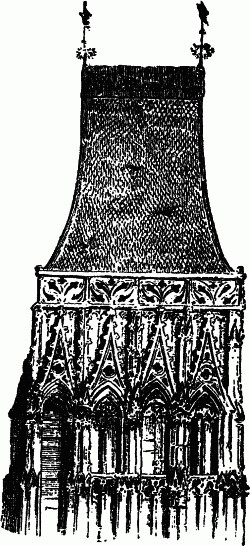

21. From this form to the true spire the change is slight, and consists in little more than various decoration; generally in putting small pinnacles at the angles, and piercing the central pyramid with traceried windows; sometimes, as at Fribourg and Burgos, throwing it into tracery altogether: but to do this is invariably the sign of a vicious style, as it takes away from the spire its character of a true roof, and turns it nearly into an ornamental excrescence. At Antwerp and Brussels, the celebrated towers (one, observe, ecclesiastical, being the tower of the cathedral, and the other secular), are formed by successions of diminishing towers, set one above the other, and each supported by buttresses thrown to the angles of the one beneath. At the English cathedrals of Lichfield and Salisbury, the spire is seen in great purity, only decorated by sculpture; but I am aware of no example so striking in its entire simplicity as that of the towers of the cathedral of Coutances in Normandy. There is a dispute between French and English antiquaries as to the date of the building, the English being unwilling to admit its complete priority to all their own Gothic. I have no doubt of this priority myself; and I hope that the time will soon come when men will cease to confound vanity with patriotism, and will think the honor of their nation more advanced by their own sincerity and courtesy, than by claims, however learnedly contested, to the invention of pinnacles and arches. I believe the French nation was, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the greatest in the world; and that the French not only invented Gothic architecture, but carried it to a perfection which no other nation has approached, then or since: but, however this may be, there can be no doubt that the towers of Coutances, if not the earliest, are among the very earliest, examples of the fully developed spire. I have drawn one of them carefully for you (fig. 11), and you will see immediately that they are literally domestic roofs, with garret windows, executed on a large scale, and in stone. Their only ornament is a kind of scaly mail, which is nothing more than the copying in stone of the common wooden shingles of the house-roof; and their security is provided for by strong gabled dormer windows, of massy masonry, which, though supported on detached shafts, have weight enough completely to balance the lateral thrusts of the spires. Nothing can surpass the boldness or the simplicity of the plan; and yet, in spite of this simplicity, the clear detaching of the shafts from the slope of the spire, and their great height, strengthened by rude cross-bars of stone, carried back to the wall behind, occasion so great a complexity and play of cast shadows, that I remember no architectural composition of which the aspect is so completely varied at different hours of the day.10 But the main thing I wish you to observe is, the complete domesticity of the work; the evident treatment of the church spire merely as a magnified house-roof; and the proof herein of the great truth of which I have been endeavoring to persuade you, that all good architecture rises out of good and simple domestic work; and that, therefore, before you attempt to build great churches and palaces, you must build good house doors and garret windows.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 12.

PLATE VII.

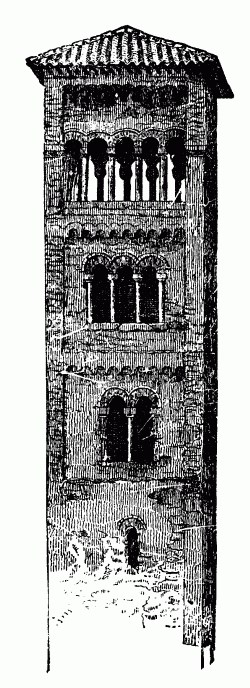

22. Nor is the spire the only ecclesiastical form deducible from domestic architecture. The spires of France and Germany are associated with other towers, even simpler and more straightforward in confession of their nature, in which, though the walls of the tower are covered with sculpture, there is an ordinary ridged gable roof on the top. The finest example I know of this kind of tower, is that on the north-west angle of Rouen Cathedral (fig. 12); but they occur in multitudes in the older towns of Germany; and the backgrounds of Albert Dürer are full of them, and owe to them a great part of their interest: all these great and magnificent masses of architecture being repeated on a smaller scale by the little turret roofs and pinnacles of every house in the town; and the whole system of them being expressive, not by any means of religious feeling,11 but merely of joyfulness and exhilaration of spirit in the inhabitants of such cities, leading them to throw their roofs high into the sky, and therefore giving to the style of architecture with which these grotesque roofs are associated, a certain charm like that of cheerfulness in a human face; besides a power of interesting the beholder which is testified, not only by the artist in his constant search after such forms as the elements of his landscape, but by every phrase of our language and literature bearing on such topics. Have not these words, Pinnacle, Turret, Belfry, Spire, Tower, a pleasant sound in all your ears? I do not speak of your scenery, I do not ask you how much you feel that it owes to the gray battlements that frown through the woods of Craigmillar, to the pointed turrets that flank the front of Holyrood, or to the massy keeps of your Crichtoun and Borthwick and other border towers. But look merely through your poetry and romances; take away out of your border ballads the word tower wherever it occurs, and the ideas connected with it, and what will become of the ballads? See how Sir Walter Scott cannot even get through a description of Highland scenery without help from the idea:—

"Each purple peak, each flinty spire,Was bathed in floods of living fire."Take away from Scott's romances the word and idea turret, and see how much you would lose. Suppose, for instance, when young Osbaldistone is leaving Osbaldistone Hall, instead of saying "The old clock struck two from a turret adjoining my bedchamber," he had said, "The old clock struck two from the landing at the top of the stair," what would become of the passage? And can you really suppose that what has so much power over you in words has no power over you in reality? Do you think there is any group of words which would thus interest you, when the things expressed by them are uninteresting?

23. For instance, you know that, for an immense time back, all your public buildings have been built with a row of pillars supporting a triangular thing called a pediment. You see this form every day in your banks and clubhouses, and churches and chapels; you are told that it is the perfection of architectural beauty; and yet suppose Sir Walter Scott, instead of writing, "Each purple peak, each flinty spire," had written, "Each purple peak, each flinty 'pediment.'"12 Would you have thought the poem improved? And if not, why would it be spoiled? Simply because the idea is no longer of any value to you; the thing spoken of is a nonentity. These pediments, and stylobates, and architraves never excited a single pleasurable feeling in you—never will, to the end of time. They are evermore dead, lifeless, and useless, in art as in poetry, and though you built as many of them as there are slates on your house-roofs, you will never care for them. They will only remain to later ages as monuments of the patience and pliability with which the people of the nineteenth century sacrificed their feelings to fashions, and their intellects to forms. But on the other hand, that strange and thrilling interest with which such words strike you as are in any wise connected with Gothic architecture—as for instance, Vault, Arch, Spire, Pinnacle, Battlement, Barbican, Porch, and myriads of such others, words everlastingly poetical and powerful whenever they occur,—is a most true and certain index that the things themselves are delightful to you, and will ever continue to be so. Believe me, you do indeed love these things, so far as you care about art at all, so far as you are not ashamed to confess what you feel about them.

24. In your public capacities, as bank directors, and charity overseers, and administrators of this and that other undertaking or institution, you cannot express your feelings at all. You form committees to decide upon the style of the new building, and as you have never been in the habit of trusting to your own taste in such matters, you inquire who is the most celebrated, that is to say, the most employed, architect of the day. And you send for the great Mr. Blank, and the Great Blank sends you a plan of a great long marble box with half-a-dozen pillars at one end of it, and the same at the other; and you look at the Great Blank's great plan in a grave manner, and you dare say it will be very handsome; and you ask the Great Blank what sort of a blank check must be filled up before the great plan can be realized; and you subscribe in a generous "burst of confidence" whatever is wanted; and when it is all done, and the great white marble box is set up in your streets, you contemplate it, not knowing what to make of it exactly, but hoping it is all right; and then there is a dinner given to the Great Blank, and the morning papers say that the new and handsome building, erected by the great Mr. Blank, is one of Mr. Blank's happiest efforts, and reflects the greatest credit upon the intelligent inhabitants of the city of so-and-so; and the building keeps the rain out as well as another, and you remain in a placid state of impoverished satisfaction therewith; but as for having any real pleasure out of it, you never hoped for such a thing. If you really make up a party of pleasure, and get rid of the forms and fashion of public propriety for an hour or two, where do you go for it? Where do you go to eat strawberries and cream? To Roslin Chapel, I believe; not to the portico of the last-built institution. What do you see your children doing, obeying their own natural and true instincts? What are your daughters drawing upon their cardboard screens as soon as they can use a pencil? Not Parthenon fronts, I think, but the ruins of Melrose Abbey, or Linlithgow Palace, or Lochleven Castle, their own pure Scotch hearts leading them straight to the right things, in spite of all that they are told to the contrary. You perhaps call this romantic, and youthful, and foolish. I am pressed for time now, and I cannot ask you to consider the meaning of the word "Romance." I will do that, if you please, in next lecture, for it is a word of greater weight and authority than we commonly believe. In the meantime, I will endeavor, lastly, to show you, not the romantic, but the plain and practical conclusions which should follow from the facts I have laid before you.

25. I have endeavored briefly to point out to you the propriety and naturalness of the two great Gothic forms, the pointed arch and gable roof. I wish now to tell you in what way they ought to be introduced into modern domestic architecture.

You will all admit that there is neither romance nor comfort in waiting at your own or at any one else's door on a windy and rainy day, till the servant comes from the end of the house to open it. You all know the critical nature of that opening—the drift of wind into the passage, the impossibility of putting down the umbrella at the proper moment without getting a cupful of water dropped down the back of your neck from the top of the door-way; and you know how little these inconveniences are abated by the common Greek portico at the top of the steps. You know how the east winds blow through those unlucky couples of pillars, which are all that your architects find consistent with due observance of the Doric order. Then, away with these absurdities; and the next house you build, insist upon having the pure old Gothic porch, walled in on both sides, with its pointed arch entrance and gable roof above. Under that, you can put down your umbrella at your leisure, and, if you will, stop a moment to talk with your friend as you give him the parting shake of the hand. And if now and then a wayfarer found a moment's rest on a stone seat on each side of it, I believe you would find the insides of your houses not one whit the less comfortable; and, if you answer me, that were such refuges built in the open streets, they would become mere nests of filthy vagrants, I reply that I do not despair of such a change in the administration of the poor laws of this country, as shall no longer leave any of our fellow creatures in a state in which they would pollute the steps of our houses by resting upon them for a night. But if not, the command to all of us is strict and straight, "When thou seest the naked, that thou cover him, and that thou bring the poor that are cast out to thy house."13 Not to the work-house, observe, but to thy house: and I say it would be better a thousandfold, that our doors should be beset by the poor day by day, than that it should be written of any one of us, "They reap every one his corn in the field, and they gather the vintage of the wicked. They cause the naked to lodge without shelter, that they have no covering in the cold. They are wet with the showers of the mountains, and embrace the rock, for want of a shelter."14

26. This, then, is the first use to which your pointed arches and gable roofs are to be put. The second is of more personal pleasurableness. You surely must all of you feel and admit the delightfulness of a bow window; I can hardly fancy a room can be perfect without one. Now you have nothing to do but to resolve that every one of your principal rooms shall have a bow window, either large or small. Sustain the projection of it on a bracket, crown it above with a little peaked roof, and give a massy piece of stone sculpture to the pointed arch in each of its casements, and you will have as inexhaustible a source of quaint richness in your street architecture, as of additional comfort and delight in the interiors of your rooms.

27. Thirdly, as respects windows which do not project. You will find that the proposal to build them with pointed arches is met by an objection on the part of your architects, that you cannot fit them with comfortable sashes. I beg leave to tell you that such an objection is utterly futile and ridiculous. I have lived for months in Gothic palaces, with pointed windows of the most complicated forms, fitted with modern sashes; and with the most perfect comfort. But granting that the objection were a true one—and I suppose it is true to just this extent, that it may cost some few shillings more per window in the first instance to set the fittings to a pointed arch than to a square one—there is not the smallest necessity for the aperture of the window being of the pointed shape. Make the uppermost or bearing arch pointed only, and make the top of the window square, filling the interval with a stone shield, and you may have a perfect school of architecture, not only consistent with, but eminently conducive to, every comfort of your daily life. The window in Oakham Castle (fig. 2) is an example of such a form as actually employed in the thirteenth century; and I shall have to notice another in the course of next lecture.

28. Meanwhile, I have but one word to say, in conclusion. Whatever has been advanced in the course of this evening, has rested on the assumption that all architecture was to be of brick and stone; and may meet with some hesitation in its acceptance, on account of the probable use of iron, glass, and such other materials in our future edifices. I cannot now enter into any statement of the possible uses of iron or glass, but I will give you one reason, which I think will weigh strongly with most here, why it is not likely that they will ever become important elements in architectural effect. I know that I am speaking to a company of philosophers, but you are not philosophers of the kind who suppose that the Bible is a superannuated book; neither are you of those who think the Bible is dishonored by being referred to for judgment in small matters. The very divinity of the Book seems to me, on the contrary, to justify us in referring every thing to it, with respect to which any conclusion can be gathered from its pages. Assuming then that the Bible is neither superannuated now, nor ever likely to be so, it will follow that the illustrations which the Bible employs are likely to be clear and intelligible illustrations to the end of time. I do not mean that everything spoken of in the Bible histories must continue to endure for all time, but that the things which the Bible uses for illustration of eternal truths are likely to remain eternally intelligible illustrations. Now, I find that iron architecture is indeed spoken of in the Bible. You know how it is said to Jeremiah, "Behold, I have made thee this day a defensed city, and an iron pillar, and brazen walls, against the whole land." But I do not find that iron building is ever alluded to as likely to become familiar to the minds of men; but, on the contrary, that an architecture of carved stone is continually employed as a source of the most important illustrations. A simple instance must occur to all of you at once. The force of the image of the Corner Stone, as used throughout Scripture, would completely be lost, if the Christian and civilized world were ever extensively to employ any other material than earth and rock in their domestic buildings: I firmly believe that they never will; but that as the laws of beauty are more perfectly established, we shall be content still to build as our forefathers built, and still to receive the same great lessons which such building is calculated to convey; of which one is indeed never to be forgotten. Among the questions respecting towers which were laid before you to-night, one has been omitted: "What man is there of you intending to build a tower, that sitteth not down first and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it?" I have pressed upon you, this evening, the building of domestic towers. You may think it right to dismiss the subject at once from your thoughts; but let us not do so, without considering, each of us, how far that tower has been built, and how truly its cost has been counted.

LECTURE II.

ARCHITECTURE

Delivered November 4, 185329. Before proceeding to the principal subject of this evening, I wish to anticipate one or two objections which may arise in your minds to what I must lay before you. It may perhaps have been felt by you last evening, that some things I proposed to you were either romantic or Utopian. Let us think for a few moments what romance and Utopianism mean.

First, romance. In consequence of the many absurd fictions which long formed the elements of romance writing, the word romance is sometimes taken as synonymous with falsehood. Thus the French talk of Des Romans, and thus the English use the word Romancing.

But in this sense we had much better use the word falsehood at once. It is far plainer and clearer. And if in this sense I put anything romantic before you, pray pay no attention to it, or to me.

30. In the second place. Because young people are particularly apt to indulge in reverie, and imaginative pleasures, and to neglect their plain and practical duties, the word romantic has come to signify weak, foolish, speculative, unpractical, unprincipled. In all these cases it would be much better to say weak, foolish, unpractical, unprincipled. The words are clearer. If in this sense, also, I put anything romantic before you, pray pay no attention to me.

31. But in the third and last place. The real and proper use of the word romantic is simply to characterize an improbable or unaccustomed degree of beauty, sublimity, or virtue. For instance, in matters of history, is not the Retreat of the Ten Thousand romantic? Is not the death of Leonidas? of the Horatii? On the other hand, you find nothing romantic, though much that is monstrous, in the excesses of Tiberius or Commodus. So again, the battle of Agincourt is romantic, and of Bannockburn, simply because there was an extraordinary display of human virtue in both these battles. But there is no romance in the battles of the last Italian campaign, in which mere feebleness and distrust were on one side, mere physical force on the other. And even in fiction, the opponents of virtue, in order to be romantic, must have sublimity mingled with their vice. It is not the knave, not the ruffian, that are romantic, but the giant and the dragon; and these, not because they are false, but because they are majestic. So again as to beauty. You feel that armor is romantic, because it is a beautiful dress, and you are not used to it. You do not feel there is anything romantic in the paint and shells of a Sandwich Islander, for these are not beautiful.

32. So, then, observe, this feeling which you are accustomed to despise—this secret and poetical enthusiasm in all your hearts, which, as practical men, you try to restrain—is indeed one of the holiest parts of your being. It is the instinctive delight in, and admiration for, sublimity, beauty, and virtue, unusually manifested. And so far from being a dangerous guide, it is the truest part of your being. It is even truer than your consciences. A man's conscience may be utterly perverted and led astray; but so long as the feelings of romance endure within us, they are unerring,—they are as true to what is right and lovely as the needle to the north; and all that you have to do is to add to the enthusiastic sentiment, the majestic judgment—to mingle prudence and foresight with imagination and admiration, and you have the perfect human soul. But the great evil of these days is that we try to destroy the romantic feeling, instead of bridling and directing it. Mark what Young says of the men of the world:—

"They, who think nought so strong of the romance,So rank knight-errant, as a real friend."And they are right. True friendship is romantic, to the men of the world—true affection is romantic—true religion is romantic; and if you were to ask me who of all powerful and popular writers in the cause of error had wrought most harm to their race, I should hesitate in reply whether to name Voltaire, or Byron, or the last most ingenious and most venomous of the degraded philosophers of Germany, or rather Cervantes, for he cast scorn upon the holiest principles of humanity—he, of all men, most helped forward the terrible change in the soldiers of Europe, from the spirit of Bayard to the spirit of Bonaparte,15 helped to change loyalty into license, protection into plunder, truth into treachery, chivalry into selfishness; and, since his time, the purest impulses and the noblest purposes have perhaps been oftener stayed by the devil, under the name of Quixotism, than under any other base name or false allegation.

33. Quixotism, or Utopianism; that is another of the devil's pet words. I believe the quiet admission which we are all of us so ready to make, that, because things have long been wrong, it is impossible they should ever be right, is one of the most fatal sources of misery and crime from which this world suffers. Whenever you hear a man dissuading you from attempting to do well, on the ground that perfection is "Utopian;" beware of that man. Cast the word out of your dictionary altogether. There is no need for it. Things are either possible or impossible—you can easily determine which, in any given state of human science. If the thing is impossible, you need not trouble yourselves about it; if possible, try for it. It is very Utopian to hope for the entire doing away with drunkenness and misery out of the Canongate; but the Utopianism is not our business—the work is. It is Utopian to hope to give every child in this kingdom the knowledge of God from its youth; but the Utopianism is not our business—the work is.

34. I have delayed you by the consideration of these two words, only in the fear that they might be inaccurately applied to the plans I am going to lay before you; for, though they were Utopian, and though they were romantic, they might be none the worse for that. But they are neither. Utopian they are not; for they are merely a proposal to do again what has been done for hundreds of years by people whose wealth and power were as nothing compared to ours;—and romantic they are not, in the sense of self-sacrificing or eminently virtuous, for they are merely the proposal to each of you that he should live in a handsomer house than he does at present, by substituting a cheap mode of ornamentation for a costly one. You perhaps fancied that architectural beauty was a very costly thing. Far from it. It is architectural ugliness that is costly. In the modern system of architecture, decoration is immoderately expensive, because it is both wrongly placed and wrongly finished. I say first, wrongly placed. Modern architects decorate the tops of their buildings. Mediæval ones decorated the bottom.16 That makes all the difference between seeing the ornament and not seeing it. If you bought some pictures to decorate such a room as this, where would you put them? On a level with the eye, I suppose, or nearly so? Not on a level with the chandelier? If you were determined to put them up there, round the cornice, it would be better for you not to buy them at all. You would merely throw your money away. And the fact is, that your money is being thrown away continually, by wholesale; and while you are dissuaded, on the ground of expense, from building beautiful windows and beautiful doors, you are continually made to pay for ornaments at the tops of your houses, which, for all the use they are of, might as well be in the moon. For instance, there is not, on the whole, a more studied piece of domestic architecture in Edinburgh than the street in which so many of your excellent physicians live—Rutland Street. I do not know if you have observed its architecture; but if you will look at it to-morrow, you will see that a heavy and close balustrade is put all along the eaves of the houses. Your physicians are not, I suppose, in the habit of taking academic and meditative walks on the roofs of their houses; and, if not, this balustrade is altogether useless,—nor merely useless, for you will find it runs directly in front of all the garret windows, thus interfering with their light, and blocking out their view of the street. All that the parapet is meant to do, is to give some finish to the façades, and the inhabitants have thus been made to pay a large sum for a piece of mere decoration. Whether it does finish the façades satisfactorily, or whether the physicians resident in the street, or their patients, are in anywise edified by the succession of pear-shaped knobs of stone on their house-tops, I leave them to tell you; only do not fancy that the design, whatever its success, is an economical one.