полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

But, by far the most important passage in which the Fox is mentioned, is that wherein is recorded the grotesque vengeance of Samson upon the Philistines: "And Samson went and caught three hundred foxes, and took firebrands, and turned tail to tail, and put a firebrand in the midst between two tails. And when he had set the brands on fire, he let them go into the standing corn of the Philistines, and burnt up both the shocks and also the standing corn, with the vineyards and olives" (Judges xv. 4, 5). Now, as this is one of the passages of Holy Writ to which great objections have been taken, it will be as well to examine these objections, and see whether they have any real force. The first of these objections is, that the number of foxes is far too great to have been caught at one time, and to this objection two answers have been given. The first answer is, that they need not have been caught at once, but by degrees, and kept until wanted. But the general tenor of the narrative is undoubtedly in favour of the supposition that this act of Samson was unpremeditated, and that it was carried into operation at once, before his anger had cooled. The second answer is, that the requisite number of Foxes might have been miraculously sent to Samson for this special purpose. This theory is really so foolish and utterly untenable, that I only mention it because it has been put forward. It fails on two grounds: the first being that a miracle would hardly have been wrought to enable Samson to revenge himself in so cruel and unjustifiable a manner; and the second, that there was not the least necessity for any miracle at all.

If we put out of our minds the idea of the English Fox, an animal comparatively scarce in this country, and solitary in its habits, and substitute the extremely plentiful and gregarious Jackal, wandering in troops by night, and easily decoyed by hunger into a trap, we shall see that double the number might have been taken, if needful. Moreover, it is not to be imagined that Samson caught them all with his own hand. He was at the head of his people, and had many subordinates at his command, so that a large number of hunters might have been employed simultaneously in the capture. In corroboration of this point, I insert an extremely valuable extract from Signor Pierotti's work, in which he makes reference to this very portion of the sacred history:—

"It is still very abundant near Gaza, Askalon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Ramleh. I have frequently met with it during my wanderings by night, and on one occasion had an excellent opportunity of appreciating their number and their noise.

"One evening in the month of January 1857, while it was raining a perfect deluge, I was obliged, owing to the dangerous illness of a friend, to return from Jerusalem to Jaffa. The depth of snow on the road over a great part of the mountain, the clayey mud in the plain, and the darkness of the night, prevented my advancing quickly; so that about half-past three in the morning I arrived on the bank of a small torrent, about half an hour's journey to the east of Ramleh. I wished to cross: my horse at first refused, but, on my spurring it, advanced and at once sank up to the breast, followed of course by my legs, thus teaching me to respect the instinct of an Arab horse for the future.

"There I stuck, without the possibility of escape, and consoled my horse and myself with some provisions that I had in my saddle-bags, shouting and singing at intervals, in the hope of obtaining succour, and of preventing accidents, as I knew that the year before a mule in the same position had been mistaken for a wild beast, and killed. The darkness was profound, and the wind very high; but, happily, it was not cold; for the only things attracted by my calls were numbers of jackals, who remained at a certain distance from me, and responded to my cries, especially when I tried to imitate them, as though they took me for their music-master.

"About five o'clock, one of the guards of the English consulate at Jerusalem came from Ramleh and discovered my state. He charitably returned thither, and brought some men, who extricated me and my horse from our unpleasant bath, which, as may be supposed, was not beneficial to our legs.

"During this most uncomfortable night, I had good opportunity of ascertaining that, if another Samson had wished to burn again the crops in the country of the Philistines, he would have had no difficulty in finding more than three hundred jackals, and catching as many as he wanted in springs, traps, or pitfalls. (See Ps. cxl. 5.)"

The reader will now see that there was not the least difficulty in procuring the requisite number of animals, and that consequently the first objection to the truth of the story is disposed of.

We will now proceed to the second objection, which is, that if the animals were tied tail to tail, they would remain on or near the same spot, because they would pull in different directions, and that, rather than run about, they would turn round and fight each other. Now, in the first place, we are nowhere told that the tails of the foxes, or jackals, were placed in contact with each other, and it is probable that some little space was left between them. That animals so tied would not run in a straight line is evident enough, and this was exactly the effect which Samson wished to produce. Had they been at liberty, and the fiery brand fastened to their tails, they would have run straight to their dens, and produced but little effect. But their captor, with cruel ingenuity, had foreseen this contingency, and, by the method of securing them which he adopted, forced them to pursue a devious course, each animal trying to escape from the dreaded firebrand, and struggling in vain endeavours to drag its companion towards its own particular den.

All wild animals have an instinctive dread of fire; and there is none, not even the fierce and courageous lion, that dares enter within the glare of the bivouac fire. A lion has even been struck in the face with a burning brand, and has not ventured to attack the man that wielded so dreadful a weapon. Consequently it may be imagined that the unfortunate animals that were used by Samson for his vindictive purpose, must have been filled with terror at the burning brands which they dragged after them, and the blaze of the fire which was kindled wherever they went. They would have no leisure to fight, and would only think of escaping from the dread and unintelligible enemy which pursued them.

When a prairie takes fire, all the wild inhabitants flee in terror, and never think of attacking each other, so that the bear, the wolf, the cougar, the deer, and the wild swine, may all be seen huddled together, their natural antagonism quelled in the presence of a common foe. So it must have been with the miserable animals which were made the unconscious instruments of destruction. That they would stand still when a burning brand was between them, and when flames sprang up around them, is absurd. That they would pull in exactly opposite directions with precisely balanced force is equally improbable, and it is therefore evident that they would pursue a devious path, the stronger of the two dragging the weaker, but being jerked out of a straight course and impeded by the resistance which it would offer. That they would stand on the same spot and fight has been shown to be contrary to the custom of animals under similar circumstances.

Thus it will be seen that every objection not only falls to the ground, but carries its own refutation, thus vindicating this episode in sacred history, and showing, that not only were the circumstances possible, but that they were highly probable. Of course every one of the wretched animals must have been ultimately burned to death, after suffering a prolonged torture from the firebrand that was attached to it. Such a consideration would, however, have had no effect for deterring Samson from employing them. The Orientals are never sparing of pain, even when inflicted upon human beings, and in too many cases they seem utterly unable even to comprehend the cruelty of which they are guilty. And Samson was by no means a favourable specimen of his countrymen. He was the very incarnation of strength, but was as morally weak as he was corporeally powerful; and to that weakness he owed his fall. Neither does he seem to possess the least trace of forbearance any more than of self-control, but he yields to his own undisciplined nature, places himself, and through him the whole Israelitish nation, in jeopardy, and then, with a grim humour, scatters destruction on every side in revenge for the troubles which he has brought upon himself by his own acts.

There is a passage in the Old Testament which is tolerably familiar to most students of the Scriptures: "Take us the foxes, the little foxes, that spoil the vines, for our vines have tender grapes" (Solomon's Song, ii. 15). In this passage allusion is made to the peculiar fondness for grapes and several other fruits which exist both in the Fox and the Jackal. Even the domesticated dog is often fond of ripe fruits, and will make great havoc among the gooseberry bushes and the strawberry beds. But both the Fox and the Jackal display a wonderful predilection for the grape above all other fruit, and even when confined and partly tamed, it is scarcely possible to please them better than by offering them a bunch of perfectly ripe grapes. The well-known fable of the fox and the grapes will occur to the mind of every one who reads the passage which has just been quoted.

There are two instances in the New Testament where the Fox is mentioned, and in both cases the allusion is made by the Lord himself. The first of these passages is the touching and well-known reproach, "The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man hath not where to lay his head" (Matt. viii. 20). The second passage is that in which He speaks of Herod as "that fox," selecting a term which well expressed the character of the cruel and cunning ruler to whom it was applied.

The reader will remember that, in the history of the last-mentioned animal an anecdote is told of a semi-tamed wolf that used to come every evening for the purpose of receiving a piece of bread. At the same monastery, three foxes used to enjoy a similar privilege. They came regularly to the appointed place, which was not that which the wolf frequented, and used to howl until their expected meal was given to them. Several companions generally accompanied them, but were always jealously driven away before the monks appeared with the bread.

THE HYÆNA

The Hyæna not mentioned by name, but evidently alluded to—Signification of the word Zabua—Translated in the Septuagint as Hyæna—A scene described by the Prophet Isaiah—The Hyæna plentiful in Palestine at the present day—its well-known cowardice and fear of man—The uses of the Hyæna and the services which it renders—The particular species of Hyæna—The Hyæna in the burial-grounds—Hunting the Hyæna—Curious superstition respecting the talismanic properties of its skin—Precautions adopted in flaying it—Popular legends of the Hyæna and its magical powers—The cavern home of the Hyæna—The Valley of Zeboim.

Although in our version of the Scriptures the Hyæna is not mentioned by that name, there are two passages in the Old Testament which evidently refer to that animal, and therefore it is described in these pages. If the reader will refer to the prophet Jeremiah, xii. 7-9, he will find these words: "I have forsaken mine house, I have left mine heritage; I have given the dearly beloved of my soul into the hand of her enemies. Mine heritage is unto me as a lion in the forest; it crieth out against me: therefore have I hated it. Mine heritage is unto me as a speckled bird; the birds round about are against her: come ye, assemble all the beasts of the field, come to devour." Now, the word zabua signifies something that is streaked, and in the Authorized Version it is rendered as a speckled bird. But in the Septuagint it is rendered as Hyæna, and this translation is thought by many critical writers to be the true one. It is certain that the word zabua is one of the four names by which the Talmudical writers mention the Hyæna, when treating of its character; and it is equally certain that such a rendering makes the passage more forcible, and is in perfect accordance with the habits of predacious animals.

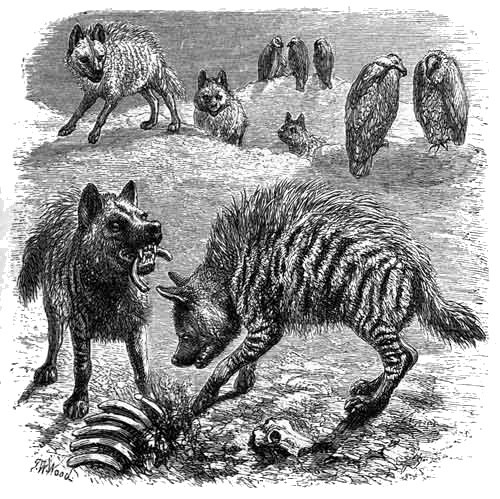

The whole scene which the Prophet thus describes was evidently familiar to him. First, we have the image of a deserted country, allowed to be overrun with wild beasts. Then we have the lion, which has struck down its prey, roaring with exultation, and defying any adversary to take it from him. Then, the lion having eaten his fill and gone away, we have the Hyænas, vultures, and other carrion-eating creatures, assembling around the carcase, and hastening to devour it. This is a scene which has been witnessed by many hunters who have pursued their sport in lands where lions, hyænas, and vultures are found; and all these creatures were inhabitants of Palestine at the time when Jeremiah wrote.

At the present day, the Hyæna is still plentiful in Palestine, though in the course of the last few years its numbers have sensibly diminished. The solitary traveller, when passing by night from one town to another, often falls in with the Hyæna, but need suffer no fear, as it will not attack a human being, and prefers to slink out of his way. But dead, and dying, or wounded animals are the objects for which it searches; and when it finds them, it devours the whole of its prey. The lion will strike down an antelope, an ox, or a goat—will tear off its flesh with its long fangs, and lick the bones with its rough tongue until they are quite cleaned. The wolves and jackals will follow the lion, and eat every soft portion of the dead animal, while the vultures will fight with them for the coveted morsels. But the Hyæna is a more accomplished scavenger than lion, wolf, jackal, or vulture; for it will eat the very bones themselves, its tremendously-powerful jaws and firmly-set teeth enabling it to crush even the leg-bone of an ox, and its unparalleled digestive powers enabling it to assimilate the sharp and hard fragments which would kill any creature not constituted like itself.

In a wild, or even a partially-inhabited country, the Hyæna is, therefore, a most useful animal. It may occasionally kill a crippled or weakly ox, and sometimes carry off a sheep; but, even in that case, no very great harm is done, for it does not meddle with any animal that can resist. But these few delinquencies are more than compensated by the great services which it renders as scavenger, consuming those substances which even the lion cannot eat, and thus acting as a scavenger in removing objects which would be offensive to sight and injurious to health.

The species which is mentioned in the Scriptures is the Striped Hyæna (Hyæna striata); but the habits of all the species are almost exactly similar. We are told by travellers of certain towns in different parts of Africa which would be unendurable but for the Hyænas. With the disregard for human life which prevails throughout all savage portions of that country, the rulers of these towns order executions almost daily, the bodies of the victims being allowed to lie where they happened to fall. No one chooses to touch them, lest they should also be added to the list of victims, and the decomposing bodies would soon cause a pestilence but for the Hyænas, who assemble at night round the bodies, and by the next morning have left scarcely a trace of the murdered men.

Even in Palestine, and in the present day, the Hyæna will endeavour to rifle the grave, and to drag out the interred corpse. The bodies of the rich are buried in rocky caves, whose entrances are closed with heavy stones, which the Hyæna cannot move; but those of the poor, which are buried in the ground, must be defended by stones heaped over them. Even when this precaution is taken, the Hyæna will sometimes find out a weak spot, drag out the body, and devour it.

In consequence of this propensity, the inhabitants have an utter detestation of the animal. They catch it whenever they can, in pitfalls or snares, using precisely the same means as were employed two thousand years ago; or they hunt it to its den, and then kill it, stripping off the hide, and carrying it about still wet, receiving a small sum of money from those to whom they show it. Afterwards the skin is dressed, by rubbing it with lime and salt, and steeping it in the waters of the Dead Sea. It is then made into sandals and leggings, which are thought to be powerful charms, and to defend the wearer from the Hyæna's bite.

THE HYÆNA.

"I have given thee for meat to the beasts of the field and to the fowls of the heaven."—Ezek. xxix. 5.

They always observe certain superstitious precautions in flaying the dead animal. Believing that the scent of the flesh would corrupt the air, they invariably take the carcase to the leeward of the tents before they strip off the skin. Even in the animal which has been kept for years in a cage, and has eaten nothing but fresh meat, the odour is too powerful to be agreeable, as I can testify from practical experience when dissecting a Hyæna that had died in the Zoological Gardens; and it is evident that the scent of an animal that has lived all its life on carrion must be almost unbearable. The skin being removed, the carcase is burnt, because the hunters think that by this process the other Hyænas are prevented from finding the body of their comrade, and either avenging its death or taking warning by its fate.

Superstitions seem to be singularly prevalent concerning the Hyæna. In Palestine, there is a prevalent idea that if a Hyæna meets a solitary man at night, it can enchant him in such a manner as to make him follow it through thickets and over rocks, until he is quite exhausted, and falls an unresisting prey; but that over two persons he has no such influence, and therefore a solitary traveller is gravely advised to call for help as soon as he sees a Hyæna, because the fascination of the beast would be neutralized by the presence of a second person. So firmly is this idea rooted in the minds of the inhabitants, that they will never travel by night, unless they can find at least one companion in their journey.

In Northern Africa there are many strange superstitions connected with this animal, one of the most curious of which is founded on its well-known cowardice. The Arabs fancy that any weapon which has killed a Hyæna, whether it be gun, sword, spear, or dagger, is thenceforth unfit to be used in warfare. "Throw away that sword," said an Arab to a French officer, who had killed a Hyæna, "it has slain the Hyæna, and it will be treacherous to you."

At the present day, its numbers are not nearly so great in Palestine as they used to be, and are decreasing annually. The cause of this diminution lies, according to Signor Pierotti, more in the destruction of forests than in the increase of population and the use of fire-arms, though the two latter causes have undoubtedly considerable influence.

There is a very interesting account by Mr. Tristram of the haunt of these animals. While exploring the deserted quarries of Es Sumrah, between Beth-arabah and Bethel, he came upon a wonderful mass of hyænine relics. The quarries in which were lying the half-hewn blocks, scored with the marks of wedges, had evidently formed the resort of Hyænas for a long series of years. "Vast heaps of bones of camels, oxen, and sheep had been collected by these animals, in some places to the depth of two or three feet, and on one spot I counted the skulls of seven camels. There were no traces whatever of any human remains. We had here a beautiful recent illustration of the mode of foundation of the old bone caverns, so valuable to the geologist. These bones must all have been brought in by the Hyænas, as no camel or sheep could possibly have entered the caverns alive, nor could any floods have washed them in. Near the entrance where the water percolates, they were already forming a soft breccia."

The second allusion to the Hyæna is made in 1 Sam. xiii. 18, "Another company turned to the way of the border that looketh to the Valley of Zeboim towards the wilderness," i.e. to the Valley of Hyænas.

The colour of the Striped Hyæna varies according to its age. When young, as is the case with many creatures, birds as well as mammals, the stripes from which it derives its name are much more strongly marked than in the adult specimen. The general hue of the fur is a pale grey-brown, over which are drawn a number of dark stripes, extending along the ribs and across the limbs.

In the young animal these stripes are nearly twice as dark and twice as wide as in the adult, and they likewise appear on the face and on other parts of the body, whence they afterwards vanish. The fur is always rough; and along the spine, and especially over the neck and shoulders, it is developed into a kind of mane, which gives a very fierce aspect to the animal. The illustration shows a group of Hyænas coming to feed on the relics of a dead animal. The jackals and vultures have eaten as much of the flesh as they can manage, and the vultures are sitting, gorged, round the stripped bones. The Hyænas are now coming up to play their part as scavengers, and have already begun to break up the bones in their crushing-mills of jaws.

THE WEASEL

Difficulty of identifying the Weasel of Scripture—The Weasel of Palestine—Suggested identity with the Ichneumon.

The word Weasel occurs once in the Holy Scriptures, and therefore it is necessary that the animal should be mentioned. There is a great controversy respecting the identification of the animal, inasmuch as there is nothing in the context which gives the slightest indication of its appearance or habits.

The passage in question is that which prohibits the Weasel and the mouse as unclean animals (see Lev. xi. 29). Now the word which is here translated Weasel is Choled, or Chol'd; and, I believe, never occurs again in the whole of the Old Testament. Mr. W. Houghton conjectures that the Hebrew word Choled is identical with the Arabic Chuld and the Syriac Chuldo, both words signifying a mole; and therefore infers that the unclean animal in question is not a Weasel, but a kind of mole.

The Weasel does exist in Palestine, and seems to be as plentiful there as in our own country. Indeed, the whole tribe of Weasels is well represented, and the polecat is seen there as well as the Weasel.

It has been suggested with much probability, that, as is clearly the case in many instances, several animals have been included in the general term Weasel, and that among them may be reckoned the common ichneumon (Herpestes), which is one of the most plentiful of animals in Palestine, and which may be met daily.

The Septuagint favours the interpretation of Weasel, and, as there is no evidence on either side, there we may allow the question to rest. As, however, the word only occurs once, and as the animal, whatever it may be, is evidently of no particular importance, we may reserve our space for the animals which have more important bearings upon the Holy Scriptures. The subject will be again mentioned in the account of the Mole of the Old Testament.

THE FERRET

Translation of the Hebrew word Anakah—The Shrew-mouse of Palestine—Etymology of the word—The Gecko or Fan-foot, its habits and peculiar cry—Repugnance felt by the Arabs of the present day towards the Gecko.

Why the Hebrew word Anakah should have been translated in our version as Ferret there is little ground for conjecture.

The name occurs among the various creeping things that were reckoned as unclean, and were prohibited as food (see Lev. xi. 29, 30): "These also shall be unclean unto you among the creeping things that creepeth upon the earth: the weasel, and the mouse, and the tortoise after his kind, and the ferret, and the chameleon, and the lizard, and the snail, and the mole." Now the word in question is translated in the Septuagint as the Mygale, or Shrew-mouse, and it is probable that this animal was accepted by the Jews as the Anakah. But, whether or not it was the Shrew-mouse, it is certain that it is not the animal which we call the Ferret. Mr. Tristram suggests that the etymology of the name, i.e. Anâkah, the Groaner, or Sigher, points to some creature which utters a mournful cry. And as the animal in question is classed among the creeping things, he offers a conjecture that the Gecko, Wall-lizard, or Fan-foot, may be the true interpretation of the word.