полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

There are few sounds which strike more awe than the Lion's roar. Even at the Zoological Gardens, where the hearer knows that he is in perfect safety, and where the Lion is enclosed in a small cage faced with strong iron bars, the sound of the terrible roar always has a curious effect upon the nerves. It is not exactly fear, because the hearer knows that he is safe; but it is somewhat akin to the feeling of mixed awe and admiration with which one listens to the crashing thunder after the lightning has sped its course. If such be the case when the Lion is safely housed in a cage, and is moreover so tame that even if he did escape, he would be led back by the keeper without doing any harm, the effect of the roar must indeed be terrific when the Lion is at liberty, when he is in his own country, and when the shades of evening prevent him from being seen even at a short distance.

In the dark, there is no animal so invisible as a Lion. Almost every hunter has told a similar story—of the Lion's approach at night, of the terror displayed by dogs and cattle as he drew near, and of the utter inability to see him, though he was so close that they could hear his breathing. Sometimes, when he has crept near an encampment, or close to a cattle inclosure, he does not proceed any farther lest he should venture within the radius illumined by the rays of the fire. So he crouches closely to the ground, and, in the semi-darkness, looks so like a large stone, or a little hillock, that any one might pass close to it without perceiving its real nature. This gives the opportunity for which the Lion has been watching, and in a moment he strikes down the careless straggler, and carries off his prey to the den. Sometimes, when very much excited, he accompanies the charge with a roar, but, as a general fact, he secures his prey in silence.

The roar of the Lion is very peculiar. It is not a mere outburst of sound, but a curiously graduated performance. No description of the Lion's roar is so vivid, so true, and so graphic as that of Gordon Cumming: "One of the most striking things connected with the Lion is his voice, which is extremely grand and peculiarly striking. It consists at times of a low, deep moaning, repeated five or six times, ending in faintly audible sighs. At other times he startles the forest with loud, deep-toned, solemn roars, repeated five or six times in quick succession, each increasing in loudness to the third or fourth, when his voice dies away in five or six low, muffled sounds, very much resembling distant thunder. As a general rule, Lions roar during the night, their sighing moans commencing as the shades of evening envelop the forest, and continuing at intervals throughout the night. In distant and secluded regions, however, I have constantly heard them roaring loudly as late as nine or ten o'clock on a bright sunny morning. In hazy and rainy weather they are to be heard at every hour in the day, but their roar is subdued."

Lastly, we come to the dwelling-place of the Lion. This animal always fixes its residence in the depths of some forest, through which it threads its stealthy way with admirable certainty. No fox knows every hedgerow, ditch, drain, and covert better than the Lion knows the whole country around his den. Each Lion seems to have his peculiar district, in which only himself and his family will be found. These animals seem to parcel out the neighbourhood among themselves by a tacit law like that which the dogs of eastern countries have imposed upon themselves, and which forbids them to go out of the district in which they were born. During the night he traverses his dominions; and, as a rule, he retires to his den as soon as the sun is fairly above the horizon. Sometimes he will be in wait for prey in the broadest daylight, but his ordinary habits are nocturnal, and in the daytime he is usually asleep in his secret dwelling-place.

We will now glance at a few of the passages in which the Lion is mentioned in the Holy Scriptures, selecting those which treat of its various characteristics.

The terrible strength of the Lion is the subject of repeated reference. In the magnificent series of prophecies uttered by Jacob on his deathbed, the power of the princely tribe of Judah is predicted under the metaphor of a Lion—the beginning of its power as a Lion's whelp, the fulness of its strength as an adult Lion, and its matured establishment in power as the old Lion that couches himself and none dares to disturb him. Then Solomon, in the Proverbs, speaks of the Lion as the "strongest among beasts, and that turneth not away for any."

Solomon also alludes to its courage in the same book, Prov. xxviii. 1, in the well-known passage, "The wicked fleeth when no man pursueth: but the righteous are bold as a lion." And, in 2 Sam. xxiii. 20, the courage of Benaiah, one of the mighty three of David's army, is specially honoured, because he fought and killed a Lion single-handed, and because he conquered "two lion-like men of Moab." David, their leader, had also distinguished himself, when a mere keeper of cattle, by pursuing and killing a Lion that had come to plunder his herd. In the same book of Samuel which has just been quoted (xvii. 10), the valiant men are metaphorically described as having the hearts of Lions.

The ferocity of this terrible beast of prey is repeatedly mentioned, and the Psalms are full of such allusions, the fury and anger of enemies being compared to the attacks of the Lion.

Many passages refer to the Lion's roar, and it is remarkable that the Hebrew language contains several words by which the different kind of roar is described. One word, for example, represents the low, deep, thunder-like roar of the Lion seeking its prey, and which has already been mentioned. This is the word which is used in Amos iii. 4, "Will a lion roar in the forest when he hath no prey?" and in this passage the word which is translated as Lion signifies the animal when full grown and in the prime of life. Another word is used to signify the sudden exulting cry of the Lion as it leaps upon its victim. A third is used for the angry growl with which a Lion resents any endeavour to deprive it of its prey, a sound with which we are all familiar, on a miniature scale, when we hear a cat growling over a mouse which she has just caught. The fourth term signifies the peculiar roar uttered by the young Lion after it has ceased to be a cub and before it has attained maturity. This last term is employed in Jer. li. 38, "They shall roar together like lions; they shall yell as lions' whelps," in which passage two distinct words are used, one signifying the roar of the Lion when searching after prey, and the other the cry of the young Lions.

The prophet Amos, who in his capacity of herdsman was familiar with the wild beasts, from which he had to guard his cattle, makes frequent mention of the Lion, and does so with a force and vigour that betoken practical experience. How powerful is this imagery, "The lion hath roared; who will not fear? The Lord God hath spoken; who can but prophesy?" Here we have the picture of the man himself, the herdsman and prophet, who had trembled many a night, as the Lions drew nearer and nearer; and who heard the voice of the Lord, and his lips poured out prophecy. Nothing can be more complete than the parallel which he has drawn. It breathes the very spirit of piety, and may bear comparison even with the prophecies of Isaiah for its simple grandeur.

It is remarkable how the sacred writers have entered into the spirit of the world around them, and how closely they observed the minutest details even in the lives of the brute beasts. There is a powerful passage in the book of Job, iv. 11, "The old lion perisheth for lack of prey," in which the writer betrays his thorough knowledge of the habits of the animal, and is aware that the usual mode of a Lion's death is through hunger, in consequence of his increasing inability to catch prey.

The nocturnal habits of the Lion and its custom of lying in wait for prey are often mentioned in the Scriptures. The former habit is spoken of in that familiar and beautiful passage in the Psalms (civ. 20), "Thou makest darkness, and it is night; wherein all the beasts of the forest do creep forth. The young Lions roar after their prey; and seek their meat from God. The sun ariseth, they gather themselves together, and lay them down in their dens."

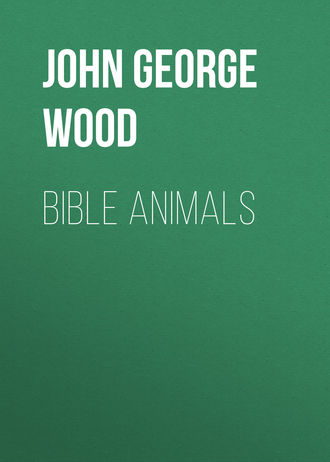

THE LION.

"The lion is come up from his thicket."—Jer. iv. 7.

"She lay down among lions, she nourished her whelps among young lions."—Ezekiel. xix. 2.

Its custom of lying in wait is frequently alluded to. See Psalm x. 9, where it is said of the wicked man, that "He lieth in wait secretly, as a lion in his den." Also, Lam. iii. 10, "He was unto me as a bear lying in wait, and as a lion in secret places." Also, Ps. xvii. 11, wherein the peculiar gait and demeanour of the Lion is admirably depicted, "They have now compassed us in our steps; they have set their eyes bowing down to the earth; like as a lion that is greedy of his prey, and as it were a young lion lurking in secret places."

The retired spots, deep in the forest, where the Lion makes his den, are repeatedly mentioned. See for example, Cant. iv. 8, "Look from the top of Amana, from the top of Shenir and Hermon, from the lions' dens." Also, Jer. iv. 7, "The lion is come up from his thicket, and the destroyer of the Gentiles is on his way." The same Prophet contains several passages illustrative of the Lion's habitation; see ch. v. 6, "Wherefore a lion out of the forest shall slay them;" xii. 8, "Mine heritage is unto me as a lion in the forest;" and lastly, xxv. 38, "He hath forsaken his covert as the lion."

An animal so destructive among the flocks and herds could not be allowed to carry out its depredations unchecked, and as we have already seen, the warfare waged against it has been so successful, that the Lions have long ago been fairly extirpated in Palestine. The usual method of capturing or killing the Lion was by pitfalls or nets, to both of which there are many references in the Scriptures.

The mode of hunting the Lion with nets was identical with that which is practised in India at the present time. The precise locality of the Lion's dwelling-place having been discovered, a circular wall of net is arranged round it, or if only a few nets can be obtained, they are set in a curved form, the concave side being towards the Lion. They then send dogs into the thicket, hurl stones and sticks at the den, shoot arrows into it, fling burning torches at it, and so irritate and alarm the animal that it rushes against the net, which is so made that it falls down and envelopes the animal in its folds. If the nets be few, the drivers go to the opposite side of the den, and induce the Lion to escape in the direction where he sees no foes, but where he is sure to run against the treacherous net. Other large and dangerous animals were also captured by the same means.

Allusions to this sort of hunting are familiar to all students of the Bible. In the book of Job, xix. 6, the writer laments that "God hath compassed me with his net," in allusion to the custom of surrounding the den of the animal. The Psalms make frequent mention of the net as used in hunting. See Ps. ix. 15, "In the net they hid is their foot taken." Ps. xxxv. 8, "Let his net that he hath hid catch himself," together with other passages. Then, the prophet Isaiah alludes to the utter helplessness of a wild animal when thus taken. Isaiah li. 20, "Thy sons have fainted, they lie at the head of all the streets, as a wild bull in a net."

Another and more common, because an easier and a cheaper method was, by digging a deep pit, covering the mouth with a slight covering of sticks and earth, and driving the animal upon the treacherous covering. It is an easier method than the net, because after the pit is once dug, the only trouble lies in throwing the covering over its mouth. But, it is not so well adapted for taking beasts alive, as they are likely to be damaged, either by the fall into the pit, or by the means used in getting them out again. Animals, therefore, that are caught in pits are generally, though not always, killed before they are taken out. The net, however, envelops the animal so perfectly, and renders it so helpless, that it can be easily bound and taken away. The hunting net is very expensive, and requires a large staff of men to work it, so that none but a rich man could use the net in hunting.

The passages in which allusion is made to the use of the pitfall in hunting are too numerous to be quoted, and it will be sufficient to mention one or two passages, such as those wherein the Psalmist laments that his enemies have hidden for him their net in a pit, and that the proud have digged pits for him.

Lions that were taken in nets seem to have been kept alive in dens, either as mere curiosities, or as instruments of royal vengeance. Such seems to have been the object of the Lions which were kept by Darius, into whose den Daniel was thrown, by royal command, and which afterwards killed his accusers when thrown into the same den. It is plain that the Lions kept by Darius must have been exceedingly numerous, because they killed at once the accusers of Daniel, who were many in number, together with their wives and children, who, in accordance with the cruel custom of that age and country, were partakers of the same punishment with the real culprits. The whole of the first part of Ezek. xix. alludes to the custom of taking Lions alive and keeping them in durance afterwards.

Sometimes the Lion was hunted as a sport, but this amusement seems to have been restricted to the great men, on account of its expensive nature. Such hunting scenes are graphically depicted in the famous Nineveh sculptures, which represent the hunters pursuing their mighty game in chariots, and destroying them with arrows. Rude, and even conventional as are these sculptures, they have a spirit, a force, and a truthfulness, that prove them to have been designed by artists to whom the scene was a familiar one. Nothing can be better than the attitudes of the Lions; and, whether they are shown in the act of striking a blow, with all the talons thrust out and the toes spread as widely as possible; whether they are springing on the chariot of the hunter, or sinking lifeless beneath his arrows, every attitude is marvellously true to nature, and makes the spectator regret that the artist should have been trammelled by the exigencies of the work on which he was engaged.

THE LEOPARD

The Leopard not often mentioned in the Scriptures—its attributes exactly described—Probability that several animals were classed under the name—How the Leopard takes its prey—Craft of the Leopard—its ravages among the flocks—The empire of man over the beast—The Leopard at Bay—Localities wherein the Leopard lives—The skin of the Leopard—Various passages of Scripture explained.

Of the Leopard but little is said in the Holy Scriptures.

In the New Testament this animal is only mentioned once, and then in a metaphorical rather than a literal sense. In the Old Testament it is casually mentioned seven times, and only in two places is the word Leopard used in the strictly literal sense. Yet, in those brief passages of Holy Writ, the various attributes of the animal are delineated with such fidelity, that no one could doubt that the Leopard was familiarly known in Palestine. Its colour, its swiftness, its craft, its ferocity, and the nature of its dwelling-place, are all touched upon in a few short sentences scattered throughout the Old Testament, and even its peculiar habits are alluded to in a manner that proves it to have been well known at the time when the words were written.

It is my purpose in the following pages to give a brief account of the Leopard of the Scriptures, laying most stress on the qualities to which allusion is made, and then to explain the passages in which the name of the animal occurs.

In the first place, it is probable that under the word Leopard are comprehended three animals, two of which, at least, were thought to be one species until the time of Cuvier. These three animals are the Leopard proper (Leopardus varius), the Ounce (Leopardus uncia), and the Chetah, or Hunting Leopard (Gueparda jubata). All these three species belong to the same family of animals; all are spotted and similar in colour, all are nearly alike in shape, and all are inhabitants of Asia, while two of them, the Leopard and the Chetah, are also found in Africa.

It is scarcely necessary to mention that the Leopard is a beast of prey belonging to the cat tribe, that its colour is tawny, variegated with rich black spots, and that it is a fierce and voracious animal, almost equally dreaded by man and beast. It inhabits many parts of Africa and Asia, and in those portions of the country which are untenanted by mankind, it derives all its sustenance from the herb-eating animals of the same tracts.

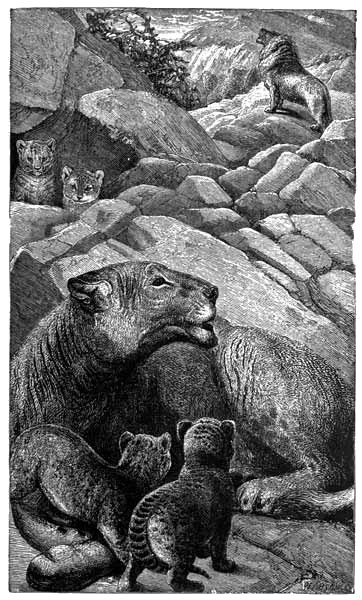

THE LEOPARD.

"As a Leopard by the way will I observe them."—Hos. xiii. 7.

To deer and antelopes it is a terrible enemy, and in spite of their active limbs, seldom fails in obtaining its prey. Swift as is the Leopard, for a short distance, and wonderful as its spring, it has not the enduring speed of the deer or antelope, animals which are specially formed for running, and which, if a limb is shattered, can run nearly as fast and quite as far on three legs as they can when all four limbs are uninjured. Instinctively knowing its inferiority in the race, the Leopard supplies by cunning the want of enduring speed.

It conceals itself in some spot whence it can see far around without being seen, and thence surveys the country. A tree is the usual spot selected for this purpose, and the Leopard, after climbing the trunk by means of its curved talons, settles itself in the fork of the branches, so that its body is hidden by the boughs, and only its head is shown between them. With such scrupulous care does it conceal itself, that none but a practised hunter can discover it, while any one who is unaccustomed to the woods cannot see the animal even when the tree is pointed out to him.

As soon as the Leopard sees the deer feeding at a distance, he slips down the tree and stealthily glides off in their direction. He has many difficulties to overcome, because the deer are among the most watchful of animals, and if the Leopard were to approach to the windward, they would scent him while he was yet a mile away from them. If he were to show himself but for one moment in the open ground he would be seen, and if he were but to shake a branch or snap a dry twig he would be heard. So, he is obliged to approach them against the wind, to keep himself under cover, and yet to glide so carefully along that the heavy foliage of the underwood shall not be shaken, and the dry sticks and leaves which strew the ground shall not be broken. He has also to escape the observation of certain birds and beasts which inhabit the woods, and which would certainly set up their alarm-cry as soon as they saw him, and so give warning to the wary deer, which can perfectly understand a cry of alarm, from whatever animal it may happen to proceed.

Still, he proceeds steadily on his course, gliding from one covert to another, and often expending several hours before he can proceed for a mile. By degrees he contrives to come tolerably close to them, and generally manages to conceal himself in some spot towards which the deer are gradually feeding their way. As soon as they are near enough, he collects himself for a spring, just as a cat does when she leaps on a bird, and dashes towards the deer in a series of mighty bounds. For a moment or two they are startled and paralysed with fear at the sudden appearance of their enemy, and thus give him time to get among them. Singling out some particular animal, he leaps upon it, strikes it down with one blow of his paw, and then, crouching on the fallen animal, he tears open its throat, and laps the flowing blood.

In this manner does it obtain its prey when it lives in the desert, but when it happens to be in the neighbourhood of human habitations, it acts in a different manner. Whenever man settles himself in any place, his presence is a signal for the beasts of the desert and forest to fly. The more timid, such as the deer and antelope, are afraid of him, and betake themselves as far away as possible. The more savage inhabitants of the land, such as the lion, leopard, and other animals, wage an unequal war against him for a time, but are continually driven farther and farther away, until at last they are completely expelled from the country. The predaceous beasts are, however, loth to retire, and do so by very slow degrees. They can no longer support themselves on the deer and antelopes, but find a simple substitute for them in the flocks and herds which man introduces, and in the seizing of which there is as much craft required as in the catching of the fleeter and wilder animals. Sheep and goats cannot run away like the antelopes, but they are penned so carefully within inclosures, and guarded so watchfully by herdsmen and dogs, that the Leopard is obliged to exert no small amount of cunning before it can obtain a meal.

Sometimes it creeps quietly to the fold, and escapes the notice of the dogs, seizes upon a sheep, and makes off with it before the alarm is given. Sometimes it hides by the wayside, and as the flock pass by it dashes into the midst of them, snatches up a sheep, and disappears among the underwood on the opposite side of the road. Sometimes it is crafty enough to deprive the fold of its watchful guardian. Dogs which are used to Leopard-hunting never attack the animal, though they are rendered furious by the sound of its voice. They dash at it as if they meant to devour it, but take very good care to keep out of reach of its terrible paws. By continually keeping the animal at bay, they give time for their master to come up, and generally contrive to drive it into a tree, where it can be shot.

But instances have been known where the Leopard has taken advantage of the dogs, and carried them off in a very cunning manner. It hides itself tolerably near the fold, and then begins to growl in a low voice. The dogs think that they hear a Leopard at a distance, and dash towards the sound with furious barks and yells. In so doing, they are sure to pass by the hiding-place of the Leopard, which springs upon them unawares, knocks one of them over, and bounds away to its den in the woods. It does not content itself with taking sheep or goats from the fold, but is also a terrible despoiler of the hen-roosts, destroying great numbers in a single night when once it contrives to find its way into the house.

As an instance of the cunning which seems innate in the Leopard, I may mention that whenever it takes up its abode near a village, it does not meddle with the flocks and herds of its neighbours, but prefers to go to some other village at a distance for food, thus remaining unsuspected almost at the very doors of the houses.

In general, it does not willingly attack mankind, and at all events seems rather to fear the presence of a full-grown man. But, when wounded or irritated, all sense of fear is lost in an overpowering rush of fury, and it then becomes as terrible a foe as the lion himself. It is not so large nor so strong, but it is more agile and quicker in its movements; and when it is seized with one of these paroxysms of anger, the eye can scarcely follow it as it darts here and there, striking with lightning rapidity, and dashing at any foe within reach. Its whole shape seems to be transformed, and absolutely to swell with anger; its eyes flash with fiery lustre, its ears are thrown back on the head, and it continually utters alternate snarls and yells of rage. It is hardly possible to recognise the graceful, lithe glossy creature, whose walk is so noiseless, and whose every movement is so easy, in the furious passion-swollen animal that flies at every foe with blind fury, and pours out sounds so fierce and menacing that few men, however well armed, will care to face it.

As is the case with most of the cat tribe, the Leopard is an excellent climber, and can ascend trees and traverse their boughs without the least difficulty. It is so fond of trees, that it is seldom to be seen except in a well-wooded district. Its favourite residence is a forest where there is plenty of underwood, at least six or seven feet in height, among which trees are sparingly interspersed. When crouched in this cover it is practically invisible, even though its body may be within arm's length of a passenger. The spotted body harmonizes so perfectly with the broken lights and deep shadows of the foliage that even a practised hunter will not enter a covert in search of a Leopard unless he is accompanied by dogs. The instinct which teaches the Leopard to choose such localities is truly wonderful, and may be compared with that of the tiger, which cares little for underwood, but haunts the grass jungles, where the long, narrow blades harmonize with the stripes which decorate its body.