полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

The Jewish Bible translates the word differently in the two passages. That in Job it renders as follows: "Who hath sent forth the wild ass free? or who hath loosed the bands of the untamed?" In the other passage, however, it follows the rendering of the Authorized Version, and gives the word as "wild asses." It is thought by several scholars that the two words refer to two different species of Wild Ass. It may be so, but as the ancient writers had the loosest possible ideas regarding distinction of species, and as, moreover, it is very doubtful whether there be any real distinction of species at all, we may allow the subject to rest, merely remembering that the rendering of the Jewish Bible, "the untamed," is a correct translation of the word Arod, though the particular animal to which it is applied may be doubtful.

We will now pass to the word about which there is no doubt whatever, namely, the Pere. This animal is clearly the species which is scientifically known as Asinus hemippus. During the summer time it has a distinct reddish tinge on the grey coat, which disappears in the winter, and the cross-streak is black. There are several kinds of Wild Ass known to science, all of which have different names. Some of our best zoologists, however, have come to the conclusion that they all really belong to the same species, differing only in slight points of structure which are insufficient to constitute separate species.

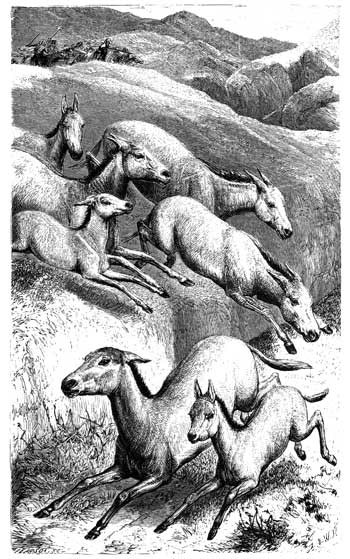

The habits of the Wild Ass are the same, whether it be the Asiatic or the African animal, and a description of one will answer equally well for the other. It is an astonishingly swift animal, so that on the level ground even the best horse has scarcely a chance of overtaking it. It is exceedingly wary, its sight, hearing, and sense of scent being equally keen, so that to approach it by craft is a most difficult task.

Like many other wild animals, it has a custom of ascending hills or rising grounds, and thence surveying the country, and even in the plains it will generally contrive to discover some earth-mound or heap of sand from which it may act as sentinel and give the alarm in case of danger. It is a gregarious animal, always assembling in herds, varying from two or three to several hundred in number, and has a habit of partial migration in search of green food, traversing large tracts of country in its passage.

It has a curiously intractable disposition, and, even when captured very young, can scarcely ever be brought to bear a burden or draw a vehicle. Attempts have been often made to domesticate the young that have been born in captivity, but with very slight success, the wild nature of the animal constantly breaking out, even when it appears to have become moderately tractable.

Although the Wild Ass does not seem to have lived within the limits of the Holy Land, it was common enough in the surrounding country, and, from the frequent references made to it in Scriptures, was well known to the ancient Jews. We will now look at the various passages in which the Wild Ass is mentioned, and begin with the splendid description in Job xxxix. 5-8:

"Who hath sent out the wild ass free? or who hath loosed the bands of the wild ass?

"Whose house I have made the wilderness, and the barren lands (or salt places) his dwellings.

"He scorneth the multitude of the city, neither regardeth he the crying of the driver.

"The range of the mountains is his pasture, and he searcheth after every green thing."

Here we have the animal described with the minuteness and truth of detail that can only be found in personal knowledge; its love of freedom, its avoidance of mankind, and its migration in search of pasture. Another allusion to the pasture-seeking habits of the animal is to be found in chapter vi. of the same book, verse 5: "Doth the wild ass bray when he hath grass?" or, according to the version of the Jewish Bible, "over tender grass?"

The same author has several other allusions to the Wild Ass. See, for example, chap. xi. 12: "For vain man would be wise, though man be born like a wild ass's colt." And in chap. xxiv. 5, in speaking of the wicked and their doings, he uses the following metaphor: "Behold, as wild asses in the desert, go they forth to their work; rising betimes for a prey: the wilderness yieldeth food for them and their children," or for the young, as the passage may be more literally rendered. The same migratory habit is also mentioned by the prophet Jeremiah (chap. xiv. 6): "And the wild asses did stand in the high places, they snuffed up the wind like dragons; their eyes did fail, because there was no grass." There is another allusion to it in Hosea viii. 9: "For they are gone up to Assyria, a wild ass alone by himself."

THE WILD ASS.

"As wild asses in the desert go they forth."—Job xxiv. 5.

Even in the earliest times of Jewish history we find a reference to the peculiar nature of this animal. In Gen. xvi. 12 it is prophesied of Ishmael, that "he will be a wild man; his hand will be against every man, and every man's hand against him; and he shall dwell in the presence of all his brethren." Now the real force of this passage is quite missed in the Authorized Version, the correct rendering being given in the Jewish Bible: "And he will be a wild ass (Pere) among men; his hand will be against all, and the hand of all against him, and in the face of all his brethren he shall dwell."

Allusion is made to the speed of the animal in Jer. ii. 24: "A wild ass used to the wilderness, that snuffeth up the wind at her pleasure; in her occasion who can turn her away? all they that seek her will not weary themselves; in her month they shall find her." The fondness of the Wild Ass for the desert is mentioned by the prophet Isaiah. Foretelling the desolation that was to come upon the land, he uses these words: "Because the palaces shall be forsaken, the multitude of the city shall be left; the forts and towers shall be for dens (or caves) for ever, and a joy of wild asses, a pasture of flocks."

These various qualities of speed, wariness, and dread of man cause the animal to be exceedingly prized by hunters, who find their utmost skill taxed in approaching it. Men of the highest rank give whole days to the hunt of the Wild Ass, and vie with each other for the honour of inflicting the first wound on so fleet an animal. With the exception of the Jews, the inhabitants of the countries where the Wild Ass lives eat its flesh, and consider it as the greatest dainty which can be found.

A very vivid account of the appearance of the animal in its wild state is given by Sir R. Kerr Porter, who was allowed by a Wild Ass to approach within a moderate distance, the animal evidently seeing that he was not one of the people to whom it was accustomed, and being curious enough to allow the stranger to approach him.

"The sun was just rising over the summit of the eastern mountains, when my greyhound started off in pursuit of an animal which, my Persians said, from the glimpse they had of it, was an antelope. I instantly put spurs to my horse, and with my attendants gave chase. After an unrelaxed gallop of three miles, we came up with the dog, who was then within a short stretch of the creature he pursued; and to my surprise, and at first vexation, I saw it to be an ass.

"Upon reflection, however, judging from its fleetness that it must be a wild one, a creature little known in Europe, but which the Persians prize above all other animals as an object of chase, I determined to approach as near to it as the very swift Arab I was on could carry me. But the single instant of checking my horse to consider had given our game such a head of us that, notwithstanding our speed, we could not recover our ground on him.

"I, however, happened to be considerably before my companions, when, at a certain distance, the animal in its turn made a pause, and allowed me to approach within pistol-shot of him. He then darted off again with the quickness of thought, capering, kicking, and sporting in his flight, as if he were not blown in the least, and the chase was his pastime. When my followers of the country came up, they regretted that I had not shot the creature when he was within my aim, telling me that his flesh is one of the greatest delicacies in Persia.

"The prodigious swiftness and the peculiar manner in which he fled across the plain coincided exactly with the description that Xenophon gives of the same animal in Arabia. But above all, it reminded me of the striking portrait drawn by the author of the Book of Job. I was informed by the Mehnander, who had been in the desert when making a pilgrimage to the shrine of Ali, that the wild ass of Irak Arabi differs in nothing from the one I had just seen. He had observed them often for a short time in the possession of the Arabs, who told him the creature was perfectly untameable.

"A few days after this discussion, we saw another of these animals, and, pursuing it determinately, had the good fortune to kill it."

It has been suggested by many zoologists that the Wild Ass is the progenitor of the domesticated species. The origin of the domesticated animal, however, is so very ancient, that we have no data whereon even a theory can be built. It is true that the Wild and the Domesticated Ass are exactly similar in appearance, and that an Asinus hemippus, or Wild Ass, looks so like an Asiatic Asinus vulgaris, or Domesticated Ass, that by the eye alone the two are hardly distinguishable from each other. But with their appearance the resemblance ends, the domestic animal being quiet, docile, and fond of man, while the wild animal is savage, intractable, and has an invincible repugnance to human beings.

This diversity of spirit in similar forms is very curious, and is strongly exemplified by the semi-wild Asses of Quito. They are the descendants of the animals that were imported by the Spaniards, and live in herds, just as do the horses. They combine the habits of the Wild Ass with the disposition of the tame animal. They are as swift of foot as the Wild Ass of Syria or Africa, and have the same habit of frequenting lofty situations, leaping about among rocks and ravines, which seem only fitted for the wild goat, and into which no horse can follow them.

Nominally, they are private property, but practically they may be taken by any one who chooses to capture them. The lasso is employed for the purpose, and when the animals are caught they bite, and kick, and plunge, and behave exactly like their wild relations of the Old World, giving their captors infinite trouble in avoiding the teeth and hoofs which they wield so skilfully. But, as soon as a load has once been bound on the back of one of these furious creatures, the wild spirit dies out of it, the head droops, the gait becomes steady, and the animal behaves as if it had led a domesticated life all its days.

THE MULE

Ancient use of the Mules—Various breeds of Mule—Supposed date of its introduction into Palestine—Mule-breeding forbidden to the Jews—The Mule as a saddle-animal—Its use on occasions of state—The king's Mule—Mules brought from Babylon after the captivity—Obstinacy of the Mule—The Mule as a beast of burden—The "Mule's burden" of earth—Mules imported by the Phœnicians—Legends respecting the Mule.

There are several references to the Mule in the Holy Scriptures, but it is remarkable that the animal is not mentioned at all until the time of David, and that in the New Testament the name does not occur at all.

The origin of the Mule is unknown, but that the mixed breed between the horse and the ass has been employed in many countries from very ancient times is a familiar fact. It is a very strange circumstance that the offspring of these two animals should be, for some purposes, far superior to either of the parents, a well-bred Mule having the lightness, surefootedness, and hardy endurance of the ass, together with the increased size and muscular development of the horse. Thus it is peculiarly adapted either for the saddle or for the conveyance of burdens over a rough or desert country.

The Mules that are most generally serviceable are bred from the male ass and the mare, those which have the horse as the father and the ass as the mother being small, and comparatively valueless. At the present day, Mules are largely employed in Spain and the Spanish dependencies, and there are some breeds which are of very great size and singular beauty, those of Andalusia being especially celebrated. In the Andes, the Mule has actually superseded the llama as a beast of burden.

Its appearance in the sacred narrative is quite sudden. In Gen. xxxvi. 24, there is a passage which seems as if it referred to the Mule: "This was that Anah that found the mules in the wilderness." Now the word which is here rendered as Mules is "Yemim," a word which is not found elsewhere in the Hebrew Scriptures. The best Hebraists are agreed that, whatever interpretation may be put upon the word, it cannot possibly have the signification that is here assigned to it. Some translate the word as "hot springs," while the editors of the Jewish Bible prefer to leave it untranslated, thus signifying that they are not satisfied with any rendering.

MULES OF THE EAST.

"Be ye not as the horse and mule, which have no under standing."—Psalm xxxii. 9.

The word which is properly translated as Mule is "Pered;" and the first place where it occurs is 2 Sam. xiii. 29. Absalom had taken advantage of a sheep-shearing feast to kill his brother Amnon in revenge for the insult offered to Tamar: "And the servants of Absalom did unto Amnon as Absalom had commanded. Then all the king's sons arose, and every man gat him up upon his mule, and fled." It is evident from this passage that the Mule must have been in use for a considerable time, as the sacred writer mentions, as a matter of course, that the king's sons had each his own riding mule.

Farther on, chap. xviii. 9 records the event which led to the death of Absalom by the hand of Joab. "And Absalom met the servants of David. And Absalom rode upon a mule, and the mule went under the thick boughs of a great oak, and his head caught hold of the oak, and he was taken up between the heaven and the earth; and the mule that was under him went away."

We see by these passages that the Mule was held in such high estimation that it was used by the royal princes for the saddle, and had indeed superseded the ass. In another passage we shall find that the Mule was ridden by the king himself when he travelled in state, and that to ride upon the king's Mule was considered as equivalent to sitting upon the king's throne. See, for example, 1 Kings i. in which there are several passages illustrative of this curious fact. See first, ver. 33, in which David gives to Zadok the priest, Nathan the prophet, and Benaiah the captain of the hosts, instructions for bringing his son Solomon to Gihon, and anointing him king in the stead of his father: "Take with you the servants of your lord, and cause Solomon my son to ride upon mine own mule, and bring him down to Gihon."

Then, in ver. 38, we are told that David's orders were obeyed, that Solomon was set on the king's Mule, was anointed by Zadok, and proclaimed as king to the people. In ver. 44 we are told how Adonijah, who had attempted to usurp the throne, and was at the very time holding a coronation feast, heard the sound of the trumpets and the shouting in honour of Solomon, and on inquiring was told that Solomon had been crowned king by Zadok, recognised by Nathan, accepted by Benaiah, and had ridden on the king's Mule. These tidings alarmed him, and caused him to flee for protection to the altar. Now it is very remarkable that in each of these three passages the fact that Solomon rode upon the king's Mule is brought prominently forward, and it was adduced to Adonijah as a proof that Solomon had been made the new king of Israel.

That the Mule should have become so important an animal seems most remarkable. In Levit. xix. 19 there is an express injunction against the breeding of Mules, and it is unlikely, therefore, that they were bred in Palestine. But, although the Jews were forbidden to breed Mules, they evidently thought that the prohibition did not extend to the use of these animals, and from the time of David we find that they were very largely employed both for the saddle and as beasts of burden. In all probability, the Mules were imported from Egypt and other countries, and that such importation was one of the means for furnishing Palestine with these animals we learn from 1 Kings x. 24, 25, in which the sacred writer enumerates the various tribute which was paid to Solomon: "All the earth sought to Solomon, to hear the wisdom which God had put in his heart.

"And they brought every man his present, vessels of silver, and vessels of gold, and garments, and armour, and spices, horses, and mules, a rate year by year." The same fact is recorded in 2 Chron. ix. 24.

In the time of Isaiah the Mule was evidently in common use as a riding animal for persons of distinction. See chap. lxvi. 20: "And they shall bring all your brethren for an offering unto the Lord, out of all nations, upon horses, and in chariots, and in litters, and upon mules, and upon swift beasts, to My holy mountain Jerusalem." Another allusion to the Mule as one of the recognised domesticated animals is found in Zech. xiv. 15: "So shall be the plague of the horse, of the mule, of the camel, and of the ass, and of all the beasts that shall be in these tents, as this plague."

The value of these animals may be inferred from the anxiety of Ahab to preserve his Mules during the long drought that had destroyed all the pasturage. "Ahab said unto Obadiah, Go into the land, unto all fountains of water, and unto all brooks: peradventure we may find grass to save the horses and mules alive, that we lose not all the beasts."

Now this Obadiah was a very great man. He was governor of the king's palace, an office which has been compared to that of our Lord High Chamberlain. He possessed such influence that, although he was known to be a worshipper of Jehovah, and to have saved a hundred prophets during Jezebel's persecution, he retained his position, either because no one dared to inform against him, or because he was too powerful to be attacked. Yet to Obadiah was assigned the joint office of seeking for pasturage for the Mules, the king himself sharing the task with his chamberlain, thus showing the exceeding value which must have been set on these appanages of royal state.

Their importance may be gathered from a passage in the Book of Ezra, in which, after enumerating with curious minuteness the number of the Jews who returned home from their Babylonish captivity, the sacred chronicler proceeds to remark that "their horses were seven hundred thirty and six; their mules, two hundred forty and five; their camels, four hundred thirty and five; their asses, six thousand seven hundred and twenty" (Ezra ii. 66, 67). There is a parallel passage in Neh. vii. 68, 69.

Seeing that the Mule was in such constant use as a riding animal, it is somewhat remarkable that we never find in the Scripture any mention of the obstinate disposition which is proverbially associated with the animal. There is only one passage which can be thought even to bear upon such a subject, and that is the familiar sentence from Ps. xxxii. 9: "Be ye not as the horse, or as the mule, which have no understanding: whose mouth must be held in with bit and bridle, lest they come near unto thee;" and, as the reader will see, no particular obstinacy or frowardness is attributed to the Mule which is not ascribed to the horse also.

Still, that the Mule was as obstinate and contentious an animal in Palestine as it is in Europe is evident from the fact that the Eastern mules of the present day are quite as troublesome as their European brethren. They are very apt to shy at anything, or nothing at all; they bite fiercely, and every now and then they indulge in a violent kicking fit, flinging out their heels with wonderful force and rapidity, and turning round and round on their fore-feet so quickly that it is hardly possible to approach them. There is scarcely a traveller in the Holy Land who has not some story to tell about the Mule and its perverse disposition; but, as these anecdotes have but very slight bearing on the subject of the Mule as mentioned in the Scriptures, they will not be given in these pages.

That the Mule was employed as a beast of burden as well as for riding, we gather from several passages in the Old Testament. See, for example, 1 Chron. xii. 40: "Moreover they that were nigh them, even unto Issachar and Zebulun and Naphtali, brought bread on asses, and on camels, and on mules, and on oxen." We have also the well-known passage in which is recorded the reply of Naaman to Elisha after the latter had cured him of his leprosy: "And Naaman said, Shall there not then, I pray thee, be given to thy servant two mules' burden of earth?" It does not necessarily follow that two of Naaman's Mules were to be laden with earth, but the probability is, that Naaman used the term "a Mule's burden" to express a certain quantity, just as we talk of a "load" of hay or gravel.

As Mules are animals of such value, we may feel some little surprise that they were employed as beasts of burden. It is possible, however, that a special and costly breed of large and handsome Mules, like those of Andalusia, were reserved for the saddle, and that the smaller and less showy animals were employed in the carriage of burdens.

Before parting entirely with the Mule, it will be well to examine the only remaining passage in which the animal is mentioned. It occurs in Ezek. xxvii. 14: "They of the house of Togarmah traded in thy fairs with horses and horsemen and mules." The chapter in which this passage occurs is a sustained lamentation over Tyre, in which the writer first enumerates the wealth and greatness of the city, and then bewails its downfall. Beginning with the words, "O Tyrus, thou hast said, I am of perfect beauty," the prophet proceeds to mention the various details of its magnificence, the number and beauty of its ships built with firs from Senir, having oars made of the oaks of Bashan, masts of the cedars of Lebanon, benches of ivory, sails of "fine linen with broidered work from Egypt," and coverings of purple and scarlet from the isles of Elishah. The rowers were from Zidon and Arvad, while Tyre itself furnished their pilots or steersmen.

After a passing allusion to the magnificent army of Tyre, the sacred writer proceeds to mention the extent of the merchandise that was brought to this queen of ancient seaports: silver and other metals were from Tarshish, slaves and brass from Meshech, ivory and ebony from Dedan, jewellery and fine linen from Syria; wheat, honey, and oil from Judæa; wine and white wool from Damascus, and so forth. And, among all these riches, are prominently mentioned the horses and Mules from Togarmah. Now, it has been settled by the best bibliographers that the Togarmah of Ezekiel is Armenia, and so we have the fact that the Phœnicians supplied themselves with Mules and horses by importing them from Armenia instead of breeding those animals themselves, just as Palestine imported its horses, and probably its Mules also, from Egypt.

It is rather remarkable that the Arabs of Palestine very seldom breed the Mule for themselves, but, like the ancient Jews, import them from adjacent countries, mostly from the Lebanon district. Those from Cyprus are, however, much valued, as they are very strong, diligent, and steady, their pace being nearly equal to that of the horse. Mules are seldom used for agricultural purposes, though they are extensively employed for riding and for carrying burdens, especially over rocky districts.

The Mule is not without its legend. One of the oddest of these accounts for its obstinacy and its incapacity for breeding.

When the Holy Family was about to travel into Egypt, St. Joseph chose a Mule to carry them. He was in the act of saddling the animal, when it kicked him after the fashion of Mules. Angry with it for such misconduct, St. Joseph substituted an ass for the Mule, thus giving the former the honour of conveying the family into Egypt, and laid a curse upon it that it should never have parents nor descendants of its own kind, and that it should be so disliked as never to be admitted into its master's house, as is the case with the horse and other domesticated animals. This is one of the multitudinous legends which are told to the crowds of pilgrims who come annually to see the miraculous kindling of the holy fire, and to visit the tree on which Judas hanged himself.