полная версия

полная версияThe American Race

From this brief presentation of the geologic evidence, the conclusion seems forced upon us that the ancestors of the American race could have come from no other quarter than western Europe, or that portion of Eurafrica which in my lectures on general ethnography I have described as the most probable location of the birth-place of the species.30

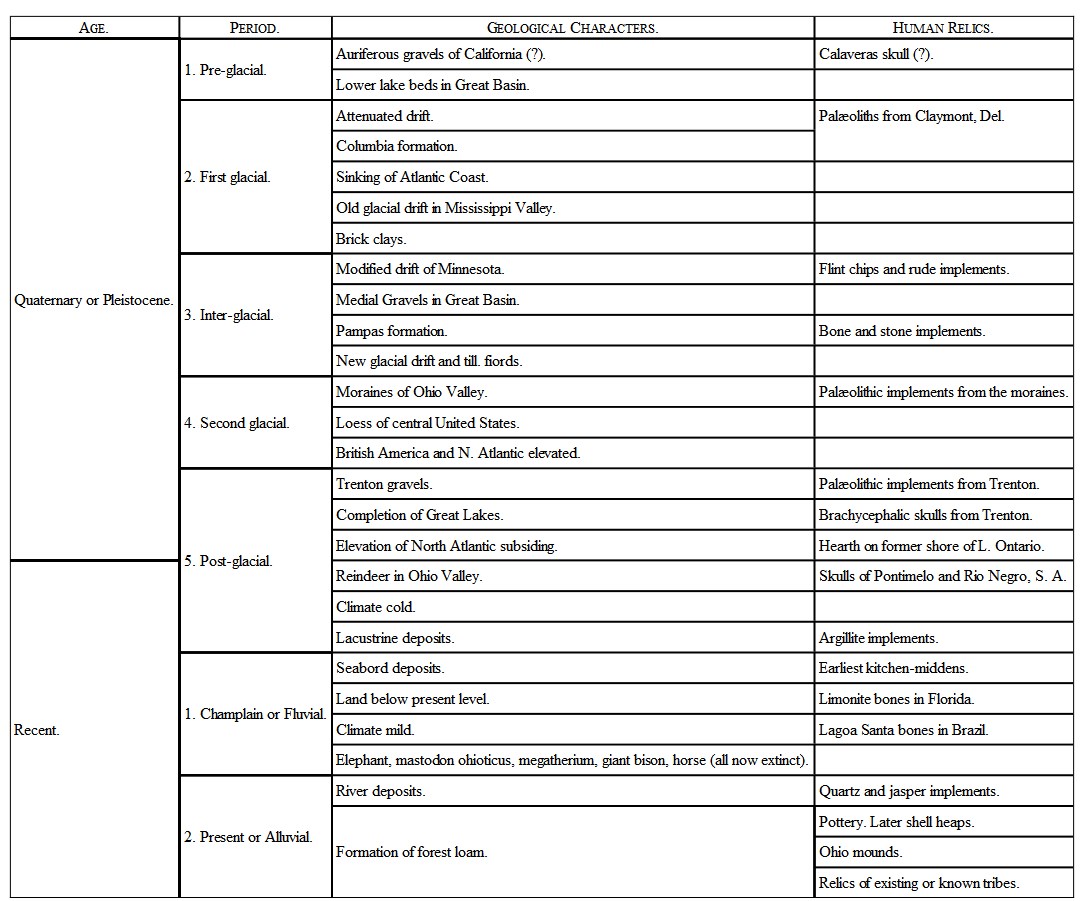

Scheme of the Age of Man in America.

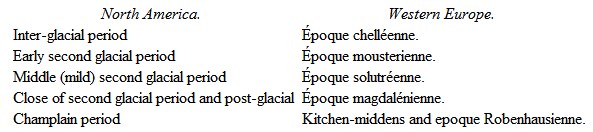

Many difficulties present themselves in bringing these periods into correspondence with the seasons of the Quaternary in Europe; but after a careful study of both continents, Mr. W. J. McGee suggests the following synchronisms:31

Of course it would not be correct to suppose that the earliest inhabitants of the continent presented the physical traits which mark the race to-day. Racial peculiarities are slowly developed in certain “areas of characterization,” but once fixed are indelible. Can we discover the whereabouts of the area which impressed upon primitive American man—an immigrant, as we have learned, from another hemisphere—those corporeal changes which set him over against his fellows as an independent race?

I believe that it was in the north temperate zone. It is there we find the oldest signs of man’s residence on the continent; it is and was geographically the nearest to the land-areas of the Old World; and so far as we can trace the lines of the most ancient migrations, they diverged from that region. But there are reasons stronger than these. The American Indians cannot bear the heat of the tropics even as well as the European, not to speak of the African race. They perspire little, their skin becomes hot, and they are easily prostrated by exertion in an elevated temperature. They are peculiarly subject to diseases of hot climates, as hepatic disorders, showing none of the immunity of the African.32 Furthermore, the finest physical specimens of the race are found in the colder regions of the temperate zones, the Pampas and Patagonian Indians in the south, the Iroquois and Algonkins in the north; whereas, in the tropics they are generally undersized, short-lived, of inferior muscular force and with slight tolerance of disease.33

These facts, taken in connection with the geologic events I have already described, would lead us to place the “area of characterization” of the native American east of the Rocky Mountains, and between the receding wall of the continental ice sheet and the Gulf of Mexico. There it was that the primitive glacial man underwent those changes which resulted in the formation of an independent race.

We have evidence that this change took place at a very remote epoch. The Swiss anatomist, Dr. J. Kollmann, has published a critical investigation of the most ancient skulls discovered in America, as the one I have already referred to from Calaveras county, California, one from Rock Bluff, Illinois, one from Pontimelo, Buenos Ayres, and others from the caverns of Lagoa Santa, Brazil, and from the loess of the Pampas. All these are credited with an antiquity going back nearly to the close of the last glacial period, and are the oldest yet found on the continent. They prove to be strictly analogous to those of the Indians of the present day. They reveal the same discrepancy in form which we now encounter in the crania of all American tribes. The Calaveras skull and that from Pontimelo are brachycephalic; those from Lagoa Santa dolichocephalic; but both possess the wide malar arches, the low orbital indices, the medium nasal apertures and the general broad faces of the present population. Dr. Kollmann, therefore, reaches the conclusion that “the variety of man in America at the close of the glacial period had the same facial form as the Indian of to-day, and the racial traits which distinguish him now, did also at that time.”

The marked diversity in cranial forms here indicated is recognizable in all parts of the continent. It has frustrated every attempt to classify the existing tribes, or to trace former lines of migration, by grouping together similar head-measurements. This was fully acknowledged by the late Dr. James Aitken Meigs, of Philadelphia, who, taking the same collection of skulls, showed how erroneous were the previous statements of Dr. Morton in his Crania Americana. The recent studies of Virchow on American crania have attained the same conclusion.34 We must dismiss as wholly untenable the contrary arguments of the French and other craniologists, and still more peremptorily those attempted identifications of American skulls with “Mongolian” or “Mongoloid” types. Such comparisons are based on local peculiarities which have no racial value.

Yet it must not be supposed from this that carefully conducted cranial comparisons between tribes and families are valueless; on the contrary, the shape and size of the skull, the proportion of the face, and many other measurements, are in the average highly distinctive family traits, and I shall frequently call attention to them.

The lowest cephalic index which I have seen reported from an American skull is 56, which is that of a perforated skull from Devil river, Michigan, now in the medical museum at Ann Arbor university;35 the highest is 97, from a Peruvian skull, though probably this was the result of an artificial deformity.

It is not necessary to conclude from these or other diversities in skull forms that the American race is a conglomerate of other and varied stocks. As I have pointed out elsewhere, the shape of the skull is not a fixed element in human anatomy, and children of the same mother may differ in this respect.36

A special feature in American skulls is the presence of the epactal bone, or os Incæ, in the occiput. It is found in a complete or incomplete condition in 3.86 per cent. of the skulls throughout the continent, and in particular localities much more frequently; among the ancient Peruvians for example in 6.08 per cent., and among the former inhabitants of the Gila valley in 6.81 per cent. This is far more frequently than in other races, the highest being the negro, which offers 2.65 per cent., while the Europeans yield but 1.19.37 The presence of the bone is due to a persistence of the transverse occipital suture, which is usually closed in fetal life. Hence it is a sign of arrested development, and indicative of an inferior race.

The majority of the Americans have a tendency to meso- or brachycephaly, but in certain families, as the Eskimos in the extreme north and the Tapuyas in Brazil, the skulls are usually decidedly long. In other instances there is a remarkable difference in members of the same tribe and even of the same household. Thus among the Yumas there are some with as low an index as 68, while the majority are above 80, and among the dolichocephalic Eskimos we occasionally find an almost globular skull. So far as can be learned, these variations appear in persons of pure blood. Often the crania differ in no wise from those of the European. Dr. Hensell, for instance, says that the skulls of pure-blood Coroados of Brazil, which he examined, corresponded in all points to those of the average German.38

The average cubical capacity of the American skull falls below that of the white, and rises above that of the black race. Taking both sexes, the Parisians of to-day have a cranial capacity of 1448 cubic centimetres; the Negroes 1344 c. c.; the American Indians 1376.39 But single examples of Indian skulls have yielded the extraordinary capacity of 1747, 1825, and even 1920 cub. cent. which are not exceeded in any other race.40

The hue of the skin is generally said to be reddish, or coppery, or cinnamon color, or burnt coffee color. It is brown of various shades, with an undertone of red. Individuals or tribes vary from the prevailing hue, but not with reference to climate. The Kolosch of the northwest coast are very light colored; but not more so than the Yurucares of the Bolivian Andes. The darkest are far from black, and the lightest by no means white.

The hair is rarely wholly black, as when examined by reflected light it will also show a faint undercolor of red. This reddish tinge is very perceptible in some tribes, and especially in children. Generally straight and coarse, instances are not wanting where it is fine and silky, and even slightly wavy or curly. Although often compared to that of the Chinese, the resemblances are superficial, as when critically examined, “the hair of the American Indian differs in nearly every particular from that of the Mongolians of eastern Asia.”41 The growth is thick and strong on the head, scanty on the body and on the face; but beards of respectable length are not wholly unknown.42

The stature and muscular force vary. The Patagonians have long been celebrated as giants, although in fact there are not many of them over six feet tall. The average throughout the continent would probably be less than that of the European. But there are no instances of dwarfish size to compare with the Lapps, the Bushmen, or the Andaman Islanders. The hands and feet are uniformly smaller than those of Europeans of the same height. The arms are longer in proportion to the other members than in the European, but not so much as in the African race. This is held to be one of the anatomical evidences of inferiority.

On the whole, the race is singularly uniform in its physical traits, and individuals taken from any part of the continent could easily be mistaken for inhabitants of numerous other parts.

This uniformity finds one of its explanations in the geographical features of the continent, which are such as to favor migrations in longitude, and thus prevent the diversity which special conditions in latitude tend to produce. The trend of the mountain chains and the flow of the great rivers in both South and North America generally follow the course of the great circles, and the migrations of native nations were directed by these geographic features. Nor has the face of the land undergone any serious alteration since man first occupied it. Doubtless in his early days the Laramie sea still covered the extensive depression in that part of our country, and it is possible that a subsidence of several hundred feet altered the present Isthmus of Panama into a chain of islands; but in other respects the continent between the fortieth parallels north and south has remained substantially the same since the close of the Tertiary Epoch.

Beyond all other criteria of a race must rank its mental endowments. These are what decide irrevocably its place in history and its destiny in time. Some who have personally studied the American race are inclined to assign its psychical potentialities a high rank. For instance, Mr. Horatio Hale hesitates not to say: “Impartial investigation and comparison will probably show that while some of the aboriginal communities of the American continent are low in the scale of intellect, others are equal in natural capacity, and possibly superior, to the highest of the Indo-European race.”43 This may be regarded as an extremely favorable estimate. Few will assent to it, and probably not many would even go so far as Dr. Amedée Moure in his appreciation of the South American Indians, which he expresses in these words: “With reference to his mental powers, the Indian of South America should be classed immediately after the white race, decidedly ahead of the yellow race, and especially beyond the African.”44

Such general opinions are interesting because both of them are the results of personal observations of many tribes. But the final decision as to the abilities of a race or of an individual must be based on actual accomplished results, not on supposed endowments. Thus appraised, the American race certainly stands higher than the Australian, the Polynesian or the African, but does not equal the Asian.

A review of the evidence bears out this opinion. Take the central social fact of government. In ancient America there are examples of firm and stable states, extending their sway widely and directed by definite policy. The league of the Iroquois was a thoroughly statesman-like creation, and the realm of Peru had a long and successful existence. That this mental quality is real is shown by the recent history of some of the Spanish-American republics. Two of them, Guatemala and Mexico, count among their ablest presidents in the present generation pure-blood American Indians.45 Or we may take up the arts. In architecture nothing ever accomplished by the Africans or Polynesians approaches the pre-Columbian edifices of the American continent. In the development of artistic forms, whether in stone, clay or wood, the American stands next to the white race. I know no product of Japanese, Chinese or Dravidian sculpture, for example, which exhibits the human face in greater dignity than the head in basalt figured by Humboldt as an Aztec priestess.46 The invention of a phonetic system for recording ideas was reached in Mexico, and is striking testimony to the ability of the natives. In religious philosophy there is ample evidence that the notion of a single incorporeal Ruler of the universe had become familiar both to Tezcucans and Kechuas previous to the conquest.

While these facts bear testimony to a good natural capacity, it is also true that the receptivity of the race for a foreign civilization is not great. Even individual instances of highly educated Indians are rare; and I do not recall any who have achieved distinction in art or science, or large wealth in the business world.

The culture of the native Americans strongly attests the ethnic unity of the race. This applies equally to the ruins and relics of its vanished nations, as to the institutions of existing tribes. Nowhere do we find any trace of foreign influence or instruction, nowhere any arts or social systems to explain which we must evoke the aid of teachers from the eastern hemisphere. The culture of the American race, in whatever degree they possessed it, was an indigenous growth, wholly self-developed, owing none of its germs to any other race, ear-marked with the psychology of the stock.

Furthermore, this culture was not, as is usually supposed, monopolized by a few nations of the race. The distinction that has been set up by so many ethnographers between “wild tribes” and “civilized tribes,” Jägervölker and Culturvölker, is an artificial one, and conveys a false idea of the facts. There was no such sharp line. Different bands of the same linguistic stock were found, some on the highest, others on the lowest stages of development, as is strikingly exemplified in the Uto-Aztecan family. Wherever there was a center of civilization, that is, wherever the surroundings favored the development of culture, tribes of different stocks enjoyed it to nearly an equal degree, as in central Mexico and Peru. By them it was distributed, and thus shaded off in all directions.

When closely analyzed, the difference between the highest and the average culture of the race is much less than has been usually taught. The Aztecs of Mexico and the Algonkins of the eastern United States were not far apart, if we overlook the objective art of architecture and one or two inventions. To contrast the one as a wild or savage with the other as a civilized people, is to assume a false point of view and to overlook their substantial psychical equality.

For these reasons American culture, wherever examined, presents a family likeness which the more careful observers of late years have taken pains to put in a strong light. This was accomplished for governmental institutions and domestic architecture by Lewis H. Morgan, for property rights and the laws of war by A. F. Bandelier, for the social condition of Mexico and Peru by Dr. Gustav Brühl, and I may add for the myths and other expressions of the religious sentiment by myself.47

In certain directions doubtless the tendency has been to push this uniformity too far, especially with reference to governmental institutions. Mr. Morgan’s assertions upon this subject were too sweeping. Nevertheless he was the first to point out clearly that ancient American society was founded, not upon the family, but upon the gens, totem or clan, as the social unit.48 The gens is “an organized body of consanguineal kindred” (Powell), either such in reality, or, when strangers have been adopted, so considered by the tribal conscience. Its members dwell together in one house or quarter, and are obliged to assist each other. An indeterminate number of these gentes, make up the tribe, and smaller groups of several of them may form “phratries,” or brotherhoods, usually for some religious purpose. Each gens is to a large extent autonomic, electing its own chieftain, and deciding on all questions of property and especially of blood-revenge, within its own limits. The tribe is governed by a council, the members of which belong to and represent the various gentes. The tribal chief is elected by this council, and can be deposed at its will. His power is strictly limited by the vote of the council, and is confined to affairs of peace. For war, a “war chief” is elected also by the council, who takes sole command. Marriage within the gens is strictly prohibited, and descent is traced and property descends in the female line only.

This is the ideal theory of the American tribal organization, and we may recognize its outlines almost anywhere on the continent; but scarcely anywhere shall we find it perfectly carried out. The gentile system is by no means universal, as I shall have occasion to point out; where it exists, it is often traced in the male line; both property and dignities may be inherited directly from the father; consanguine marriage, even that of brother and sister or father and daughter, though rare, is far from unexampled.49 In fact, no one element of the system was uniformly respected, and it is an error of theorists to try to make it appear so. It varied widely in the same stock and in all its expressions.50 This is markedly true, for instance, in domestic architecture. The Lenâpé, who were next neighbors to the Five Nations, had nothing resembling their “long house,” on which Morgan founded his scheme of communal tenements; and the efforts which some later writers have made to identify the large architectural works of Mexico and Yucatan with the communal pueblos of the Gila valley will not bear the test of criticism.

The foundation of the gentile, as of any other family life, is, as I have shown elsewhere,51 the mutual affection between kindred. In the primitive period this is especially between the children of the same mother, not so much because of the doubt of paternity as because physiologically and obviously it is the mother in whom is formed and from whom alone proceeds the living being. Why this affection does not lead to the marriage of uterine brothers and sisters—why, on the contrary, there is almost everywhere a horror of such unions—it is not easy to explain. Darwin suggests that the chief stimulus to the sexual feelings is novelty, and that the familiarity of the same household breeds indifference; and we may accept this in default of a completer explanation. Certainly, as Moritz Wagner has forcibly shown,52 this repugnance to incest is widespread in the species, and has exerted a powerful influence on its physical history.

In America marriage was usually by purchase, and was polygamous. In a number of tribes the purchase of the eldest daughter gave the man a right to buy all the younger daughters, as they reached nubile age. The selection of a wife was often regarded as the concern of the gens rather than of the individual. Among the Hurons, for instance, the old women of the gens selected the wives for the young men, “and united them with painful uniformity to women several years their senior.”53 Some control in this direction was very usual, and was necessary to prevent consanguine unions.

The position of women in the social scheme of the American tribes has often been portrayed in darker colors than the truth admits. As in one sense a chattel, she had few rights against her husband; but some she had, and as they were those of her gens, these he was forced to respect. Where maternal descent prevailed, it was she who owned the property of the pair, and could control it as she listed. It passed at her death to her blood relatives and not to his. Her children looked upon her as their parent, but esteemed their father as no relation whatever. An unusually kind and intelligent Kolosch Indian was chided by a missionary for allowing his father to suffer for food. “Let him go to his own people,” replied the Kolosch, “they should look after him.” He did not regard a man as in any way related or bound to his paternal parent.

The women thus made good for themselves the power of property, and this could not but compel respect. Their lives were rated at equal or greater value than a man’s;54 instances are frequent where their voice was important in the council of the tribe; nor was it very rare to see them attaining the dignity of head chief. That their life was toilsome is true; but its dangers were less, and its fatigues scarce greater, than that of their husbands. Nor was it more onerous than that of the peasant women of Europe to-day.

Such domestic arrangements seem strange to us, but they did not exclude either conjugal or parental affection. On the contrary, the presence of such sentiments has impressed travelers among even the rudest tribes, as the Eskimos, the Yumas and the hordes of the Chaco;55 and Miss Alice Fletcher tells me she has constantly noted such traits in her studies of life in the wigwam. The husband and father will often undergo severe privations for his wife and children.

The error to which I have referred of classifying the natives into wild and civilized tribes has led to regarding the one as agricultural, and the other as depending exclusively on hunting and fishing. Such was not the case. The Americans were inclined to agriculture in nearly all regions where it was profitable. Maize was cultivated both north and south to the geographical extent of its productive culture; beans, squashes, pumpkins, and potatoes were assiduously planted in suitable latitudes; the banana was rapidly accepted after its introduction, even by tribes who had never seen a white man; cotton for clothing and tobacco as a luxury were staple crops among very diverse stocks. The Iroquois, Algonkins and Muskokis of the Atlantic coast tilled large fields, and depended upon their harvests for the winter supplies. The difference between them and the sedentary Mexicans or Mayas in this respect was not so wide as has been represented.

It was a serious misfortune for the Americans that the fauna of the continent did not offer any animal which could be domesticated for a beast of draft or burden. There is no doubt but that the horse existed on the continent contemporaneously with post-glacial man; and some palæontologists are of opinion that the European and Asian horses were descendants of the American species;56 but for some mysterious reason the genus became extinct in the New World many generations before its discovery. The dog, domesticated from various species of the wolf, was a poor substitute. He aided somewhat in hunting, and in the north as an animal of draft; but was of little general utility. The lama in the Cordilleras in South America was prized principally for his hair, and was also utilized for burdens, but not for draft.57 Nor were there any animals which could be domesticated for food or milk. The buffalo is hopelessly wild, and the peccary, or American hog, is irreclaimable in its love of freedom.

We may say that America everywhere at the time of the discovery was in the polished stone age. It had progressed beyond the rough stone stage, but had not reached that of metals. True that copper, bronze and the precious ores were widely employed for a variety of purposes; but flaked and polished stone remained in all parts the principal material selected to produce a cutting edge. Probably three-fourths of the tribes were acquainted with the art of tempering and moulding clay into utensils or figures; but the potter’s wheel and the process of glazing had not been invented. Towns and buildings were laid out with a correct eye, and stone structures of symmetry were erected; but the square, the compass, the plumb line, and the scales and weight had not been devised.58 Commodious boats of hollowed logs or of bark, or of skins stretched on frames, were in use on most of the waters; but the inventive faculties of their makers had not reached to either oars or sails to propel them,59 the paddle alone being relied upon, and the rudder to guide them was unknown. The love of music is strong in the race, and wind instruments and those sounded by percussion had been devised in considerable variety; but the highest type, the string instruments, were beyond their capacity of invention.