полная версия

полная версияThe American Race

We have already seen that the Caribs were represented here by the Palmellas, and the Arawaks by the Moxos and Baures. South of the Moxos was the extensive region of the Chiquitos, stretching between south latitude 16° and 18°, and from the upper affluents of the Paraguay river to the summit of the Cordillera. On the south it adjoined the Gran Chaco, and on the west the territory of the Kechuas. They were a medium-sized, mild-mannered people, mostly of little culture, depending on the chase for food, but willingly adopting the agricultural life recommended to them by the missionaries. They were divided into a vast number of small roving bands, the most important group of which were the Manacicas, whose homes were near Lake Xaray, about the head-waters of the Paraguay. Their myths relating to a male and female deity and their son reminded the Jesuits of the Christian Trinity.465 The Manacicas were agriculturists and remarkably skilful potters. The villages they constructed were surrounded with palisades and divided by broad streets. The corpses of the dead were deposited in underground vaults, and both property and rank passed in the male line to the sons of the deceased.

The Chiquito language is interesting for its scope and flexibility, being chiefly made up of generic particles capable of indefinite combination.466 It is singular in having no numerals, not even as far as three. Its four principal dialects were those of the Taos, the Piñocos, the Manacicas and the Penoquies.467 It was selected by the missionaries as the medium of instruction for a number of the neighboring tribes.

Of such tribes there were many, widely different in speech, manners and appearance from the Chiquitos. Some of them are particularly noteworthy for their un-Indian type. Thus, to the west of the Chiquitos, on the banks of the rivers Mamore and Chavari, were the Yurucares, the Tacanas and the Mosetenas, all neighbors, and though not of one tongue, yet alike in possessing a singularly white skin and fine features. Their color is as light and as really white as many southern Europeans, the face is oval, the nose straight, fine, and often aquiline, the lips thin, the cheek-bones not prominent, the eyes small, dark and horizontal, the expression free and noble. They are of pure blood, and the most important tribe of them derived their name, Yurucares, white men, from their Kechua neighbors before the conquest. They are usually uncommonly tall (1.75), bold warriors, lovers of freedom and given to a hunting life. The women are often even taller and handsomer than the men.

The traveler D’Orbigny suggested that this light color arose from their residence under the shade of dense forests in a hot and humid atmosphere. He observed that many of them had large patches of albinism on their persons.468

The branches of these stocks may be classed as follows:

YURUCARI LINGUISTIC STOCKConis.

Cuchis.

Enetés.

Mages.

Mansiños.

Oromos.

Solostos.

MOSETENA LINGUISTIC STOCKChimanis.

Magdalenos.

Maniquies.

Muchanis.

Tucupis.

The Toromonas occupy the tract between the Madre de Dios and the Madidi, from 12° to 13° south latitude. According to D’Orbigny they are, together with the Atenes, Cavinas, Tumupasas and Isuiamas, members of one stock, speaking dialects of the Tacana language. He was unable to procure a vocabulary of it, and only learned that it was exceedingly guttural and harsh.469 From their position and their Kechua name (tuyu), low or swamp land, I am inclined to identify the Toromonas with the Tuyumiris or Pukapakaris, who are stated formerly to have dwelt on the Madre de Dios and east of the Rio Urubamba, and to have been driven thence by the Sirineris (Tschudi).

According to recent authorities the Cavinas speak the same tongue as the Araunas on the Madre de Dios, which are separated from the Pacaguaras by the small river Genichiquia;470 and as the language of the Toromonas is called in the earlier accounts of the missions Macarani, I may make out the following list of the members of the

TACANA LINGUISTIC STOCKAraunas.

Atenes.

Cavinas.

Equaris.

Isuiamas.

Lecos.

Macaranis.

Maropas.

Pukapakaris.

Sapiboconas.

Tacanas.

Toromonas.

Tumupasas.

Tuyumiris.

The Araunas are savage, and according to Heath “cannibals beyond a doubt.” He describes them as “gaunt, ugly, and ill formed,” wearing the hair long and going naked.471 Colonel Labré, however, who visited several of their villages in 1885, found them sedentary and agricultural, with temples and idols, the latter being geometrical figures of polished wood and stone. Women were considered impure, were not allowed to know even the names of the gods, and were excluded from religious rites.472 The Cavinas, on the other hand, are described by early writers as constructing houses of stone.473 The Maropas, on the east side of the river Beni near the little town of Reyes, speak a dialect of Tacana as close to it as Portuguese to Spanish. They are erroneously classed as a distinct nation by D’Orbigny, who obtained only a few words of their tongue. The Sapiboconas, who lived at the Moxos Mission, and of whose dialect Hervas supplies a vocabulary, are also a near branch of the stock. We now have sufficient material to bring these tribes into relation. With them I locate the Lecos, the tribe who occupied the mission of Aten, and are therefore called also Atenianos.474 At present some civilized Lecos live at the mission of Guanay, between the Beni and Titicaca; but we have nothing of their language.475

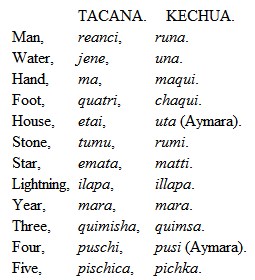

The Tacana dialects present a number of verbal analogies to Kechua and Aymara; so many in fact that they testify to long inter-communion between the stocks, though I think not to a radical identity. I present a few:

The numerals above “two” have clearly been borrowed from the Kechua-Aymara.

There are also a large number of verbal coincidences between the Tacana and the Pano groups, but not enough to allow us to suppose an original unity.

The Samucus (Zamucas) embraced a number of sub-tribes dwelling on the northern border of the Chaco, between 18° and 20° south latitude, and about the river Oxuquis. They did not resemble the Chaco stocks, as they were not vagrant hunters, but dwelt in fixed villages, and pursued an agricultural life.476 Their language was singularly sweet in sound, and was called by D’Orbigny “the Italian of the forest.” They included the following members:

SAMUCU LINGUISTIC STOCKCareras.

Cayporotades.

Coroinos.

Cuculados.

Guaranocas.

Ibirayas.

Morotocos.

Potureros.

Satienos.

Tapios.

Ugaronos.

Among these the Morotocos are said to have offered the rare spectacle of a primitive gynocracy. The women ruled the tribe, and obliged the men to perform the drudgery of house-work. The latter were by no means weaklings, but tall and robust, and daring tiger-hunters. The married women refused to have more than two children, and did others come they were strangled.

On the river Mamore, between 13° and 14° of south latitude, were the numerous villages of the Canichanas or Canisianas. They were unusually dark in complexion and ugly of features; nor did this unprepossessing exterior belie their habits or temperament. They were morose, quarrelsome, tricky and brutal cannibals, preferring theft to agriculture, and prone to drunkenness; but ingenious and not deficient in warlike arts, constructing strong fortifications around their villages, from which they would sally forth to harass and plunder their peaceable neighbors. By a singular anomaly, this unpromising tribe became willing converts to the teachings of the Jesuits, and of their own accord gathered into large villages in order to secure the presence of a missionary.477 Their language has no known affinities. It is musical, with strong consonantal sounds, and like some of the northern tongues, makes a distinction between animate and inanimate objects, or those so considered.478

Between 13° and 14° of south latitude, on the west bank of the Rio Mamore, were the Cayubabas or Cayuvavas, speaking a language without known affinities, though containing words from a number of contiguous tongues.479 The men are tall and robust, with regular features and a pleasant expression. The missionaries found no difficulty in bringing them into the fold, but they obstinately retained some of their curious ancient superstitions, as, for instance, that a man should do no kind of work while his wife had her monthly illness; and should she die, he would undertake no enterprise of importance so long as he remained a widower.480

Brief notices will suffice of the various other tribes, many of them now extinct, who centered around the missions of the Chiquitos and Moxos early in this century.

The Apolistas took their name from the river Apolo, an affluent of the Beni, about south latitude 15°. They were contiguous to the Aymaras, and had some physical resemblance to them. From their position, I suspect they belong in the Tacana group.

The Chapacuras, or more properly Tapacuras, were on the Rio Blanco or Baures in the province of Moxos. They called themselves Huachis, and the Quitemocas are mentioned as one of their sub-tribes. Von Martius thinks they were connected with the Guaches of Paraguay, a mixed tribe allied to the Guaycuru stock of the Chaco. The resemblance is very slight.

The Covarecas were a small band at the mission of Santa Anna, about south latitude 17°. Their language was practically extinct in 1831.

The Curaves and the Curuminacas, the former on the Rio Tucubaca and the latter north of them near the Brazil line, were said to have independent languages; but both were extinct at the time of D’Orbigny’s visit in 1831. The same was true of the Corabecas and Curucanecas.

The Ites or Itenes were upon the river Iten, an affluent of the Mamore about 12° south latitude. They were sometimes improperly called Guarayos, a term which, like Guaycurus, Aucas, Yumbos and others, was frequently applied in a generic sense by the Spanish Americans to any native tribe who continued to live in a savage condition.

The Movimas (Mobimas) occupied the shores of the Rio Yacuma, and Rio Mamore about 14° south latitude. In character and appearance they were similar to the Moxos, but of finer physique, “seldom ever under six feet,” says Mr. Heath. They are now civilized, and very cleanly in their habits. The vocabularies of their language show but faint resemblances with any other.

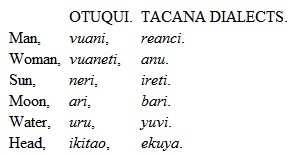

The Otuquis, who in 1831 did not number over 150 persons, lived in the northeast part of the province of Chiquitos near the Brazilian line. Their language was nearly extinct at that time. The short vocabulary of it preserved by D’Orbigny does not disclose connections with other stocks, unless it be a distant affinity with the Tacana group. This may be illustrated by the following words:

It was the policy of the Jesuits in their missions in this district to gather the tribes from the forest and mountain into permanent settlements, and reduce as far as possible the number of languages and dialects, so as to facilitate instruction in religious teaching. Shortly after this Order was expelled from their missions (1767), an official report on their “reductions” was printed in Peru, giving a list of the tribes at each station, and the languages in use for instruction.481 From this scarce work I extract a few interesting particulars.

The province of Apolobamba is described as extending about eighty leagues northeast-southwest, east of the Cordillera, and west of the Rio Beni. The languages adopted in it were the Leca, spoken by the Lecos Indians at the mission of Aten, and the Maracani, at the mission of Tumupasa, on the Rio Beni. Forty-nine nations are named as belonging to the mission of the Chiquitos, each of whom is stated to have spoken a different language or dialect, though all were instructed in their religious duties in Chiquito. At the mission of Moxos twenty-nine tribes are named as in attendance, but it had not been found possible, such was the difference of their speech, to manage with less than nine languages, to wit, the Moxa, the Baure, the Mure, the Mobima, the Ocorona, the Cayubaba, the Itonama and the Maracani.482

Of these tongues I have classed the Leca and Maracani as dialects of the Takana, not from comparison of vocabularies, for I have seen none of either, but from the locations of the tribes speaking them. The Moxa and Baure are dialects of the Arawak stock. The Mura is a branch of the Tupi, spoken by the powerful tribe of the Muras on the Medeira and Amazon, who distinctly recalled in tradition their ancestral home in the west.483 The Chiquito, the Mobima, the Caniciana (Canichana), the Cayubaba, the Itonama and the Ocorona remain so far irreducible stocks. Vocabularies of the first five have been preserved, but nothing of the Ocorona. It is probably identical with the Rocorona, in which Professor Teza has published some texts.484 I have not been able to identify it with any other tongue. Hervas unites both with the Herisebocona as a single stock.485

2. THE PAMPEAN REGION

South of the dividing upland which separates the waters of the Amazon from those which find their way to the Rio de la Plata, the continent extends in broad level tracts, watered by numerous navigable streams and rich in game and fish. Its chief physical features are the wooded and rolling Chaco in the north, the treeless and grassy Pampas to the south, and the sterile rocky plains of Patagonia still further toward the region of cold. In the west the chain of the Cordilleras continues to lift its summits to an inaccessible height until they enter Patagonia, when they gradually diminish to a range of hills.

The tribes of all this territory, both east and west of the Andes, belong ethnographically together, and not with the Peruvian stocks. What affinities they present to others to the north are with those of the Amazonian regions.

1. The Gran Chaco and its Stocks. The Guaycurus, Lules, Matacos and Payaguas. The Charruas, Guatos, Calchaquis, etc

The great streams of the Parana and Paraguay offer a natural boundary between the mountainous country of southern Brazil and the vast plains of the Pampas formation. In their upper course these rivers form extensive marshes, which in the wet season are transformed into lakes on which tangled masses of reeds and brushwood, knitted together by a lush growth of vines, swim in the lazy currents as floating islands. These were the homes of some wild tribes who there found a secure refuge, the principal of whom were the Caracaras, who came from the lower Parana, and were one of the southernmost offshoots of the Tupi family.486

For five hundred miles west of the Parana and extending nearly as far from north to south, is a wide, rolling country, well watered, and usually covered with dense forests, called El Gran Chaco.487 Three noble rivers, the Pilcomayo, the Vermejo and the Salado, intersect it in almost parallel courses from northwest to southeast.

Abounding in fish and game and with a mild climate, the Chaco has always been densely peopled, and even to-day its native population is estimated at over twenty thousand. But the ethnology of these numerous tribes is most obscure. The Jesuit missionaries asserted that they found eight totally different languages on the Rio Vermejo alone,488 and the names of the tribes run up into the hundreds.

As is generally the case with such statements, distant dialects of the same stock were doubtless mistaken for radically distinct tongues. From all the material which is accessible, I do not think that the Chaco tribes number more than five stocks, even including those who spoke idioms related to the Guarani or Tupi. The remainder are the Guaycuru, the Mataco, the Lule and the Payagua. This conclusion is identical with that reached by the Argentine writer, Don Luis J. Fontana, except that he considers the Chunipi independent, while I consider that it is a member of the Mataco stock.

One of the best known members of the Guaycuru stock was the tribe of the Abipones, whose manners and customs were rendered familiar in the last century through the genial work of the Styrian missionary, Martin Dobrizhoffer.489 They were an equestrian people, proud of their horsemanship and their herds, and at that time dwelt on the Paraguay river, but by tradition had migrated from the north.

The Guaycurus proper were divided into three gentes (parcialidades) located with reference to the cardinal points. On the north were the Epicua-yiqui; on the west the Napin-yiqui, and on the south the Taqui-yiqui. Their original home was on the Rio Paraguay, two hundred leagues from its mouth, but later they removed to the banks of the Pilcomayo. Their system was patriarchal, the sons inheriting direct from the father, and they were divided into hereditary castes, from which it was difficult to emerge. These were distinguished by different colors employed in painting the skin. The highest caste, the nabbidigan, were distinguished by black.490

The Abipones were almost entirely destroyed early in this century by the Tobas and Mbocobis,491 and probably at present they are quite extinct. The Tobas are now the most numerous tribe in the Chaco, and their language the most extended.492 They remain savage and untamable, and it was to their ferocity that Dr. Crévaux, the eminent French geographer and anthropologist, fell a victim in recent years. The dialects of the Abipones, Mbocobis and Tobas were “as much alike as Spanish and Portuguese” (Dobrizhoffer).

The Guachis speak a rather remote dialect of the stock, but undoubtedly connected with the main stem. According to the analogy of many of their words and the tenor of tradition, they at one time lived in the Bolivian highlands, in the vicinity of the Moxos and Chiquitos. It is probable that they are now nearly extinct, as for several generations infanticide has been much in vogue among them, prompted, it is said, by superstitious motives. Forty years ago an inconspicuous remnant of them were seen by Castelnau and Natterer in the vicinity of Miranda.493

The Malbalas, who were a sub-tribe of the Mbocobis, dwelling on the Rio Vermejo, are described as light in color, with symmetrical figures and of kindly and faithful disposition. Like most of the Chaco tribes, they were monogamous, and true to their wives.494

The Terenos and the Cadioéos still survive on the upper Paraguay, and are in a comparatively civilized condition. The latter manufacture a pottery of unusually excellent quality.495

On the authority of Father Lozano I include in this stock the Chichas-Orejones, the Churumatas, that branch of the Mataguayos called Mataguayos Churumatas (from the frequent repetition of the syllable chu in their dialect), the Mbocobis and Yapitalaguas, whose tongues were all closely related to the Toba;496 while Dr. Joao Severiano da Fonseca has recently shown that the Quiniquinaux is also a branch of this stock.497

The Lules are a nation which has been a puzzle for students of the ethnography of the Chaco. They were partly converted by the celebrated Jesuit missionary and eminent linguist, Father Alonso de Barcena, in 1690, who wrote a grammar of their language, which he called the Tonicote. The Jesuit historian of Paraguay, Del Techo, states that three languages were spoken among them, the Tonicote, the Kechua and the Cacana, which last is a Kechua term from caca, mountain, and in this connection means the dialect of the mountaineers. Barcena’s converts soon became discontented and fled to the forests, where they disappeared for thirty years or more. About 1730, a number of them reappeared near the Jesuit mission of the Chaco, and settled several towns on the rivers Valbuena and Salado. There their language was studied by the missionaries. A grammar of it was composed by Machoni,498 and a vocabulary collected by the Abbé Ferragut.499 Meanwhile the work of Barcena had disappeared, and the Abbé Hervas expressed a doubt whether the Lule of Machoni was the same as that of his predecessor. He advanced the opinion that the ancient Lule was the Cacana; that the modern were not the descendants of the ancient Lules, and that the Mataras of the Chaco were the Tonicotes to whom Barcena was apostle.500

The missionary Lozano to some extent clears up this difficulty. He states that the Lules or Tonicotes were divided into the greater and lesser Lules, and it is only the latter to which the name properly belonged. The former were divided into three bands, the Isistines, the Oristines, and the Toquistines.501 None of these latter existed under these names at the close of the last century, and at present no tribe speaking the Lule of Machoni is known in the Chaco. The language has evident affinities both with the Vilela and the Mataco,502 but also presents many independent elements. The statement of Hervas, copied by various subsequent writers,503 that the ancient or greater Lules spoke the Cacana, and that this was a different stock from the Lule of Machoni, lacks proof, as we have no specimen of the Cacana, and not even indirect knowledge of its character. Indeed, Del Techo says definitely that the missionaries of the earliest period, who were familiar with the Lule of that time, had to employ interpreters in ministering to the Cacanas.504

The modern Vilelas live on the Rio Salado, between 25° and 26° south latitude. I find in it so many words of such character that I am inclined to take it as the modern representative of the Lule of Machoni, though corrupted by much borrowing. When we have a grammar of it, the obscurity will be cleared up.

A comparison of the Vilela with the Chunipi, (Chumipy, Sinipi or Ciulipi,) proves that they are rather closely related, and that the Chunipi is not an independent tongue as has often been stated. In view of this, I include it in the Lule dialects.

The third important stock is that of the Matacos. It is still in extensive use on the Rio Vermejo, and we have a recent and genial description of these people and their language from the pen of the Italian traveler, Giovanni Pelleschi.505 They are somewhat small in size, differing from the Guaycurus in this respect, who are tall. Their homes are low huts made of bushes, but they are possessed of many small arts, are industrious, and soon become conversant with the use of tools. Their hair is occasionally wavy, and in children under twelve, it is often reddish. The eyes are slightly oblique, the nose large, straight and low. Like all the Chaco Indians, they do not care for agriculture, preferring a subsistence from hunting and fishing, and from the product of their horses and cattle. What few traditions they have indicate a migration from the east.

The term Mataguayos was applied to some of this stock as well as to some of the Guaycurus. The former included the Agoyas, the Inimacas or Imacos, and the Palomos, to whom the Jesuit Joseph Araoz went as missionary, and composed a grammar and dictionary of their dialect. He describes them as exceedingly barbarous and intractable.506 The Tayunis had at one time 188 towns, and the Teutas 46 towns. This was in the palmy days of the Jesuit reductions.507 Both these extensive tribes are classed by D’Orbigny with the Matacos.

According to the older writers the Payaguas lived on the river Paraguay, and spoke their tongue in two dialects, the Payagua and the Sarigue. Von Martius, however, denies there ever was such a distinct people. The word payagua, he remarks, was a generic term for “enemies,” and was applied indiscriminately to roving hordes of Guaycurus, Mbayas, etc.508