полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

Although the pre-Celtic languages were ultimately displaced by the Celtic—it is uncertain when this process was completed—the influence of ancient Oriental culture remained. In Scotland the pig-taboo, with its history rooted in ancient Egypt, has had tardy survival until our own times. It has no connection with Celtic culture, for the Continental Celts were a pig-rearing and pork-eating people, like the Ægæan invaders of Greece. The pig-taboo is still as prevalent in Northern Arcadia as in the Scottish Highlands, where the descendants not only of the ancient Iberians but of intruders from pork-loving Ireland and Scandinavia have acquired the ancient prejudice and are now perpetuating it.

Some centuries before the Roman occupation, a system of gold coinage was established in England. Trade with the Continent appears to have greatly increased in volume and complexity. England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland were divided into small kingdoms. The evidence afforded by the Irish Gaelic manuscripts, which refer to events before and after the Roman conquest of Britain, shows that society was well organized and that the organization was of non-Roman character. Tacitus is responsible for the statement that the Irish manners and customs were similar to those prevailing in Britain, and he makes reference to Irish sea-trade and the fact that Irish sea-ports were well known to merchants. England suffered more from invasions before and after the arrival of Julius Cæsar than did Scotland or Ireland. It was consequently incapable of united action against the Romans, as Tacitus states clearly. The indigenous tribes refused to be allies of the intruders.201

In Ireland, which Pliny referred to as one of the British Isles, the pre-Celtic Firbolgs were subdued by Celtic invaders. The later "waves" of Celts appeared to have subdued the earlier conquerors, with the result that "Firbolg" ceased to have a racial significance and was applied to all subject peoples. There were in Ireland, as in England, upper and lower classes, and military tribes that dominated other tribes. Withal, there were confederacies, and petty kings, who owed allegiance to "high kings". The "Red Branch" of Ulster, of which Cuchullin was an outstanding representative, had their warriors trained in Scotland. It may be that they were invaders who had passed through Scotland into Northern Ireland; at any rate, it is unlikely that they would have sent their warriors to a "colony" to acquire skill in the use of weapons. There were Cruithne (Britons) in all the Irish provinces. Most Irish saints were of this stock.

The pre-Roman Britons had ships of superior quality, as is made evident by the fact that a British squadron was included in the great Veneti fleet which Cæsar attacked and defeated with the aid of Pictones and other hereditary rivals of the Veneti and their allies. In early Roman times Britain thus took an active part in European politics in consequence of its important commercial interests.

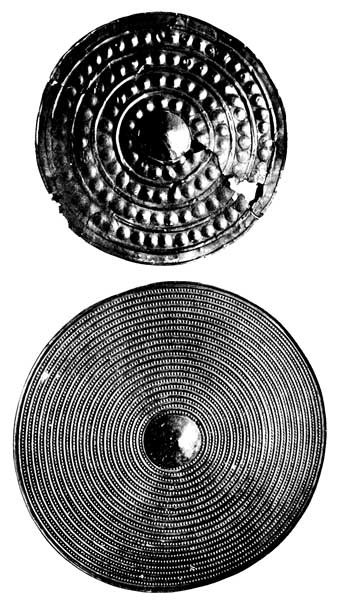

BRONZE BUCKLERS OR SHIELDS

(British Museum)

Upper: from the Thames. Lower: from Wales.

When the Romans reached Scotland the Caledonians, a people with a Celtic tribal name, were politically predominant. Like the English and Irish pre-Roman peoples, they used chariots and ornamented these with finely worked bronze. Enamel was manufactured or imported. Some of the Roman stories about the savage condition of Scotland may be dismissed as fictions. Who can nowadays credit the statement of Herodian202 that the warriors of Scotland in Roman times passed their days in the water, or Dion Cassius's203 story that they were wont to hide in mud for several days with nothing but their heads showing, and that despite their fine physique they fed chiefly on herbs, fruit, nuts, and the bark of trees, and, withal, that they had discovered a mysterious earth-nut and had only to eat a piece no larger than a bean to defy hunger and thirst. The further statement that the Scottish "savages" were without state or family organization hardly accords with historical facts. Even Agricola had cause to feel alarm when confronted by the well-organized and well-equipped Caledonian army at the battle of Mons Grampius, and he found it necessary to retreat afterwards, although he claimed to have won a complete victory. His retreat appears to have been as necessary as that of Napoleon from Moscow. The later invasion of the Emperor Severus was a disastrous one for him, entailing the loss of 50,000 men.

A people who used chariots and horses, and artifacts displaying the artistic skill of those found in ancient Britain, had reached a comparatively high state of civilization. Warriors did not manufacture their own chariots, the harness of their horses, their own weapons, armour, and ornaments; these were provided for them by artisans. Such things as they required and could not obtain in their own country had to be imported by traders. The artisans had to be paid in kind, if not in coin, and the traders had to give something in return for what they received. Craftsmen and traders had to be protected by laws, and the laws had to be enforced.

The evidence accumulated by archæologists is sufficient to prove that Britain had inherited from seats of ancient civilization a high degree of culture and technical skill in metal-working, &c., many centuries before Rome was built. The finest enamel work on bronze in the world was produced in England and Ireland, and probably, although definite proof has not yet been forthcoming, in Scotland, the enamels of which may have been imported and may not. Artisans could not have manufactured enamel without furnaces capable of generating a high degree of heat. The process was a laborious and costly one. It required technical knowledge and skill on the part of the workers. Red, white, yellow, and blue enamels were manufactured. Even the Romans were astonished at the skill displayed in enamel work by the Britons. The people who produced these enamels and the local peoples who purchased them, including the Caledonians, were far removed from a state of savagery.

Many writers, who have accepted without question the statements of certain Roman writers regarding the early Britons and ignored the evidence that archæological relics provide regarding the arts and crafts and social conditions of pre-Roman times, have in the past written in depreciatory vein regarding the ancestors of the vast majority of the present population of these islands, who suffered so severely at the altar of Roman ambition. Everything Roman has been glorified; Roman victories over British "barbarians" have been included among the "blessings" of civilization. Yet "there is", as Elton says, "something at once mean and tragical about the story of the Roman conquest.... On the one side stand the petty tribes, prosperous nations in minature, already enriched by commerce and rising to a homely culture; on the other the terrible Romans strong in their tyranny and an avarice which could never be appeased."204

It was in no altruistic spirit that the Romans invaded Gaul and broke up the Celtic organization, or that they invaded Briton and reduced a free people to a state of bondage. The life blood of young Britain was drained by Rome, and, for the loss sustained, Roman institutions, Roman villas and baths, and the Latin language and literature were far from being compensations. Rome was a predatory state. When its military organization collapsed, its subject states fell with it. Gaul and Britain had been weakened by Roman rule; the ancient spirit of independence had been undermined; native initiative had been ruthlessly stamped out under a system more thorough and severe than modern Prussianism. At the same time, there is, of course, much to admire in Roman civilization.

During the obscure post-Roman period England was occupied by Angles and Saxons and Jutes, who have been credited with the wholesale destruction of masses of the Britons. The dark-haired survivors were supposed to have fled westward, leaving the fair intruders in undisputed occupation of the greater part of England. But the indigenous peoples of the English mining areas were originally a dark-haired and sallow people, and the invading Celts were mainly a fair people. Boadicea was fair-haired like Queen Maeve of Ireland. The evidence collected of late years by ethnologists shows that the masses of the English population are descended from the early peoples of the Pre-Agricultural and Early Agricultural Ages. The theory of the wholesale extermination by the Anglo-Saxons of the early Britons has been founded manifestly on very scant and doubtful evidence.

What the Teutonic invasions accomplished in reality was the destruction not of a people but of a civilization. The native arts and crafts declined, and learning was stamped out, when the social organization of post-Roman Britain was shattered. On the Continent a similar state of matters prevailed. Roman civilization suffered decline when the Roman soldier vanished.

Happily, the elements of "Celtic" civilization had been preserved in those areas that had escaped the blight of Roman ambition. The peoples of Celtic speech had preserved, as ancient Gaelic manuscripts testify, a love of the arts as ardent as that of Rome, and a fine code of chivalry to which the Romans were strangers. The introduction of Christianity had advanced this ancient Celtic civilization on new and higher lines. When the Columban missionaries began their labours outside Scotland and Ireland, they carried Christianity and "a new humanism" over England and the Continent, "and became the teachers of whole nations, the counsellors of kings and emperors". Ireland and Scotland had originally received their Christianity from Romanized England and Gaul. The Celtic Church developed on national lines. Vernacular literature was promoted by the Celtic clerics.

In England, as a result of Teutonic intrusions and conquests, Christianity and Romano-British culture had been suppressed. The Anglo-Saxons were pagans. In time the Celtic missionaries from Scotland and Ireland spread Christianity and Christian culture throughout England.

It is necessary for us to rid our minds of extreme pro-Teutonic prejudices. Nor is it less necessary to avoid the equally dangerous pitfall of the Celtic hypothesis. Christianity and the associated humanistic culture entered these islands during the Roman period. In Ireland and Scotland the new religion was perpetuated by communities that had preserved pre-Roman habits of life and thought which were not necessarily of Celtic origin or embraced by a people who can be accurately referred to as the "Celtic race". The Celts did not exterminate the earlier settlers. Probably the Celts were military aristocrats over wide areas.

Before the fair Celts had intruded themselves in Britain and Ireland, the seeds of pre-Celtic culture, derived by trade and colonization from centres of ancient civilization through their colonies, had been sown and had borne fruit. The history of British civilization begins with neither Celt nor Roman, but with those early prospectors and traders who entered and settled in the British Isles when mighty Pharaohs were still reigning in Egypt, and these and the enterprising monarchs in Mesopotamia were promoting trade and extending their spheres of influence. The North Syrian or Anatolian carriers of Eastern civilization who founded colonies in Spain before 2500 b.c. were followed by Cretans and Phœnicians. The sea-trade promoted by these pioneers made possible the opening up of overland trade routes. It was after Pytheas had (about 300 b.c.) visited Britain by coasting round Spain and Northern France from Marseilles that the volume of British trade across France increased greatly and the sea-routes became of less importance. When Carthage fell, the Romans had the trade of Western Europe at their mercy, and their conquests of Gaul and Britain were undoubtedly effected for the purpose of enriching themselves at the expense of subject peoples. We owe much to Roman culture, but we owe much also to the culture of the British pre-Roman period.

1

Book of Llan Daf.

2

Dr. Hugh Cameron Gillies in Home Life of the Highlanders, Glasgow, 1911, pp. 85 et seq.

3

A pestle or stone was used to pound grain in hollowed slabs or rocks before the mechanical mill was invented.

4

Primitive Man.

5

Men of the Old Stone Age (1916), pp. 240-1.

6

British Museum—A Guide to the Antiquities of the Stone Age, p. 76 (1900).

7

Miller had adopted the "stratification theory" of Professor William Robertson of Edinburgh University, who, in his The History of America (1777), wrote: "Men in their savage state pass their days like the animals round them, without knowledge or veneration of any superior power".

8

Custom and Myth (1910 edition), p. 13. Lang's views regarding flints are worthless.

9

The last division of the Tertiary period.

10

It must be borne in mind that the lengths of these periods are subject to revision. Opinion is growing that they were not nearly so long as here stated.

11

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. XLIII, 1913.

12

For principal references see The Races of Europe, W. Z. Ripley, pp. 172 et seq., and The Anthropological History of Europe, John Beddoe (Rhind lectures for 1891; revised edition, 1912), p. 47.

13

That is, the tall representatives of the Crô-Magnon races.

14

Men of the Old Stone Age, pp. 335-6.

15

Myths of the New World, p. 163.

16

Cults of the Greek States, Vol. V. p. 243.

17

Budge, Gods of the Egyptians. Vol. I, p. 203.

18

De Groot, The Religious System of China, Book I, pp. 216-7.

19

Ibid., Book I, pp. 28 and 332.

20

I am indebted to the Abbé Breuil for this information which he gave me during the course of a conversation.

21

Budge, Gods of the Egyptians, Vol. I, p. 358. These scarabs have not been found in the early Dynastic graves. Green malachite charms, however, were used in even the pre-Dynastic period.

22

The Myths of the New World, p. 294. According to Bancroft the green stones were often placed in the mouths of the dead.

23

Laufer, Jade, pp. 294 et seq. (Chicago, 1912).

24

Men of the Old Stone Age, pp. 297-8.

25

Primitive Man (Proceedings of the British Academy, Vol. VII).

26

Les Grottes de Grimaldi (Baousse-Rousse), Tome I, fasc. II—Géologie et Paléontologie (Monaco, 1906), p. 123.

27

Prehistoric Britain, pp. 142-3.

28

London, 1917.

29

Shells as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture, pp. 84-91.

30

G. A. Reisner. Early Dynastic Cemeteries of Naga-ed-Der, Vol. I, 1908, Plates 6 and 7.

31

Jackson's Shells, pp. 128, 174, 176, 178.

32

Dr. Alexander Carmichael, Carmina Gadeiica, Vol. II, pp.247 et seq. Mr. Wilfrid Jackson, author of Shells as Evidence of the Migrations of Early Culture, tells me that the "blue-eyed limpet" is our common limpet—Patella vulgata—the Lepas, Patelle, Jambe, Œil de boue, Bernicle, or Flie of the French. In Cornwall it is the "Crogan", the "Bornigan", and the "Brennick". It is "flither" of the English, "flia" of the Faroese, and "lapa" of the Portuguese. A Cornish giant was once, according to a folk-tale, set to perform the hopeless task of emptying a pool with a single limpet which had a hole in it. Limpets are found in early British graves and in the "kitchen middens". They are met with in abundance in cromlechs, on the Channel Isles and in Brittany, covering the bones and the skulls of the dead. Mr. Jackson thinks they were used like cowries for vitalizing and protecting the dead.

33

Breasted, Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt, p. 130.

34

Hamlet, V. i.

35

Men of the Old Stone Age, pp.304-5.

36

A Red Sea cowry shell (Cyprœa minor) found on the site of Hurstbourne station (L. & S. W. Railway, main line) in Hampshire, was associated with "Early Iron Age" artifacts. (Paper read by J. R. le B. Tomlin at meeting of Linnæan Society, June 14, 1921.)

37

For references see my Myths of Crete and Pre-Hellenic Europe, pp.30-31.

38

Notes to Thalaba, Book V, Canto 36.

39

Henry V, V, iii, 6.

40

For other examples see Mr. Legge's article in Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archæology, 1899. p. 310.

41

The Abbé Breuil, having examined the artifacts associated with the Western Scottish harpoons, inclines to refer to the culture as "Azilian-Tardenoisian". At the same time he considers the view that Maglemosian influence was operating is worthy of consideration. He notes that traces of Maglemosian culture have been reported from England. The Abbé has detected Magdalenian influence in artifacts from Campbeltown, Argyllshire (Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in Scotland, 1921-2).

42

Eirikr Magnusson in Notes on Shipbuilding and Nautical Terms, London, 1906.

43

Pronounced ma-haw'-baw'-rata (the two final a's are short).

44

The Orkneyinga Saga, p. 182, Edinburgh, 1873, and Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Vol. VIII.

45

Clement Reid, Submerged Forests, pp. 45-7. London, 1913.

46

The dates of the greatest disasters on record are 1421, 1532, and 1570. There were also terrible inundations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and in 1825 and 1855.

47

It was not necessarily barbarous because metal weapons had not been invented.

48

Submerged Forests, p. 120.

49

The Cairo Scientific Journal, Vol. III. No. 32 (May, 1909), p. 105.

50

Antiquity of Man in Europe, p. 274, Edinburgh, 1914. The term "Neolithic" is here rather vague. It applies to the Azilians and Maglemosians as well as to later peoples.

51

Breasted, A History of Egypt, pp. 96-7.

52

Wollaston, Pygmies and Papuans (The Stone Age To-day in Dutch New Guinea), London, 1912, pp. 53 et seq.

53

Westervelt, Legends of Old Honolulu, pp. 97 et seq.

54

Lyell, Antiquity of Man, p. 48.

55

Cæsar's Gallic War, Book III, c. 13-15.

56

Agricola, Chap. XII.

57

Smith, Roman Empire.

58

Strabo—IV, c. 1-13.

59

Satapatha-Brahmana, Pt. V, "Sacred Books of the East", XLIV, pp. 187, 203, 236. 239, 348-50.

60

Proceedings of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, 1921.

61

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1917-18, pp. 149 et seq.

62

See my Myths of Crete and pre-Hellenic Europe under "Obsidian" in Index.

63

R. W. Cochrane Patrick, Early Records relating to Mining in Scotland. Edinburgh, 1878, p. xxviii.

64

The Damnonii or Dumnonii.

65

The Fir-domnann were known as "the men who used to deepen the earth", or "dig pits". Professor J. MacNeil in Labor Gabula, p. 119. They were thus called "Diggers" like the modern Australians. The name of the goddess referred to the depths (the Underworld). It is probable she was the personification of the metal-yielding earth.

66

Alford, A Report on Ancient and Prospective Gold Mining in Egypt, 1900, and Mining in Egypt (by Egyptologist).

67

Celtic Britain, pp. 44 et seq. (4th edition).

68

Rough Stone Monuments, London, 1912, pp. 147-8.

69

The Scottish pearling beds have suffered great injury in historic times. They are the property of the "Crown", and no one takes any interest in them except the "pearl poachers".

70

L'Anthropologie, 1921, contains a long account of his discoveries.

71

The colours blue and green were obtained from copper.

72

Nat. Hist., VII, 56 (57), § 197.

73

Timagenes (c. 85-5 b.c.), an Alexandrian historian, wrote a history of the Gauls which was made use of by Ammianus Marcellinus (a.d. fourth century), a Greek of Antioch, and the author of a history of the Roman Emperors.

74

Prehistoric Britain, p. 145.

75

The Relationship between the Geographical Distribution of Megalithic Monuments and Ancient Mines, pp. 21 et seq.

76

A worm crept from the heart of a dead Phœnix, and gave origin to a new Phœnix.—Herodotus, II, 73.

77

Rendel Harris, The Ascent of Olympus, p. 2.

78

Annals of Tacitus, Book XIV, Chapter 29-30.

79

The Journal of Egyptian Archæology, Vol. I, part I, pp. 18-19.

80

It may be that Celtic chronology will have to be readjusted in the light of recent discoveries.

81

Iliad, XXIII, 75 (Lang, Leaf, and Myers' translation, p. 452).

82

The Mythology of the Eddas, pp. 538-9 (Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature, second series, Vol. XII).

83

Boudicca was her real name.

84

Introduction to O'Curry's Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, Vol. I, pp. ccclxix et seq.

85

Orcas is a Celtic word signifying "young boar".

86

Celtic Britain, p. 44.

87

Ep. X, 22.

88

Celtic Britain (4th edition), p. 212.

89

Tacitus, Agricola, Chap. XII.