полная версия

полная версияNotes on the Floridian Peninsula; its Literary History, Indian Tribes and Antiquities

Turning our attention now to this latter land, we should have cause to be surprised did we not find signs that such adventurous navigators as the Caribs had planned and executed incursions and settlements there. That these signs are so sparse and unsatisfactory, we owe not so much to their own rarity as to the slight weight attached to such things by the early explorers and discoverers. From the accounts we do possess, however, there can be no doubt but that vestiges of the Caribbean tongue, if not whole tribes identical with them in language and customs, have been met with from time to time on the peninsula.159 The striking similarity in the customs of flattening the forehead, in poisoning weapons, in the use of hollow reeds to propel arrows, in the sculpturing on war clubs, construction of dwellings, exsiccation of corpses,160 burning the houses of the dead, and other rites, though far from conclusive are yet not without a decided weight. It is much to be regretted that Adair has left us no fuller information of those seven tribes on the Koosah river, who spoke a different tongue from the Muskohge and preserved “a fixed oral tradition that they formerly came from South America, and after sundry struggles in defence of liberty settled their present abode.”161

Thus it clearly appears that the frame, so to speak, of the traditions preserved by Bristock actually did exist and may be proved from other writers. But we are still more strongly convinced that his account is at least founded on fact, when we compare the manners and customs, of the Apalachites, as he gives them, with those of the Cherokee, Choktah, Chickasah, and Muskohge, tribes plainly included by him under this name, and proved by the philological researches of Gallatin to have occupied the same location since De Soto’s expedition.162 We need have no suspicion that he plagiarized from other authors, as the particulars he mentions are not found in earlier writers; and it was not till 1661 that the English settled Carolina, not till 1699 that Iberville built his little fort on the Bay of Biloxi, and many years elapsed between this latter and the general treaty of Oglethorpe. If then we find a close similarity in manners, customs, and religions, we must perforce concede his accounts, such as they have reached us, a certain degree of credit.

He begins by stating that Apalacha was divided into six provinces; Dumont,163 writing from independent observation about three-fourths of a century afterwards, makes the same statement. Their towns were inclosed with stakes or live hedges, the houses built of stakes driven into the ground in an oval shape, were plastered with mud and sand, whitewashed without, and some of a reddish glistening color within from a peculiar kind of sand, thatched with grass, and only five or six feet high, the council-house being usually on an elevation.164 If the reader will turn to the authorities quoted in the subjoined note, he will find this an exact description of the towns and single dwellings of the later Indians.165 The women manufactured mats of down and feathers with the same skill that a century later astonished Adair,166 and spun like these the wild hemp and the mulberry bark into various simple articles of clothing. The fantastic custom of shaving the hair on one-half the head, and permitting the other half to remain, on certain emergencies, is also mentioned by later travellers.167 Their food was not so much game as peas, beans, maize, and other vegetables, produced by cultivation; and the use of salt obtained from vegetable ashes, so infrequent among the Indians, attracted the notice of Bristock as well as Adair.168 Their agricultural character reminds us of the Choktahs, among whom the men helped their wives to labor in the field, and whom Bernard Romans169 called “a nation of farmers.” In Apalache, says Dumont,170 “we find a less rude, more refined nation, peopling its meads and fertile vales, cultivating the earth, and living on the abundance of excellent fruit it produces.”

Strange as a fairy tale is Bristock’s description of their chief temple and the rites of their religion—of the holy mountain Olaimi lifting its barren, round summit far above the capital city Melilot at its base—of the two sacred caverns within this mount, the innermost two hundred feet square and one hundred in height, wherein were the emblematic vase ever filled with crystal water that trickled from the rock, and the “grand altar” of one round stone, on which incense, spices, and aromatic shrubs were the only offerings—of the platform, sculptured from the solid rock, where the priests offered their morning orisons to the glorious orb of their divinity at his daily birth—of their four great annual feasts—all reminding us rather of the pompous rites of Persian or Peruvian heliolatry than the simple sun worship of the Vesperic tribes. Yet in essentials, in stated yearly feasts, in sun and fire worship, in daily prayers at rising and setting sun, in frequent ablution, we recognize through all this exaggeration and coloring, the religious habits that actually prevailed in those regions. Indeed, the speculative antiquarian may ask concerning Mount Olaimi itself, whether it may not be identical with the enormous mass of granite known as “The Stone Mountain” in De Kalb county, Georgia, whose summit presents an oval, flat, and naked surface two or three hundred yards in width, by about twice that in length, encircled by the remains of a mural construction of unknown antiquity, and whose sides are pierced by the mouths of vast caverns;171 or with Lookout mountain between the Coosa and Tennessee rivers, where Mr. Ferguson found a stone wall “thirty-seven roods and eight feet in length,” skirting the brink of a precipice at whose base were five rooms artificially constructed in the solid rock.172

One of the most decisive proofs of the veracity of Bristock’s narrative is his assertion that they mummified the corpses of their chiefs previous to interment. Recent discoveries of such mummies leave us no room to doubt the prevalence of this custom among various Indian tribes east of the Mississippi. It is of so much interest to the antiquarian, that I shall add in an Appendix the details given on this point by later writers, as well as an examination of the origin of those mummies that have been occasionally disinterred in the caves of Tennessee and Kentucky.173

One other topic for examination in Bristock’s memoir yet remains—the scattered words of the language he mentions. The principal are the following;174

Mayrdock—the Viracocha of their traditions.

Naarim—the month of March.

Theomi—proper name of the Gulf of Mexico.

Jauas—priests.

Tlatuici—the mountain tribes.

Paracussi—chief; a generic term.

Bersaykau—vale of cedars.

Akueyas—deer.

Hitanachi—pleasant, beautiful.

Tonatzuli—heavenly singer; the name of a bird sacred to the sun.

Several of these words may be explained from tongues with which we are better acquainted.

Jauas and Pâracussi are words used in the sense they here bear in many early writers; the derivation of the former will be considered hereafter; that of the latter is uncertain. Tlatuici is doubtless identical with Tsalakie, the proper appellation of the Cherokee tribe. Akueyas has a resemblance, though remote, to the Seminole ekko of the same signification. In hitanachi we recognize the Choktah intensitive prefix hhito; and in tonatzuli a compound of the Choktah verb taloa, he sings, in one of its forms, with shutik, Muskohge sootah, heaven or sky. A closer examination would doubtless reveal other analogies, but the above are sufficient to show that these were no mere unmeaning words, coined by a writer’s fancy.

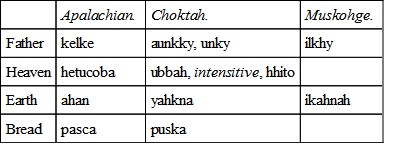

The general result of these inquiries, therefore, is strongly in favor of the authenticity of Bristock’s narrative. Exaggerated and distorted though it be, nevertheless it is the product of actual observation, and deserves to be classed among our authorities, though as one to be used with the greatest caution. We have also found that though no general migration took place from the continent southward, nor from the islands northward, yet there was considerable intercourse in both directions; that not only the natives of the greater and lesser Antilles and Yucatan, but also numbers of the Guaranay stem of the southern continent, the Caribs proper, crossed the Straits of Florida and founded colonies on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico; that their customs and language became to a certain extent grafted upon those of the earlier possessors of the soil; and to this foreign language the name Apalache belongs. As previously stated, it was used as a generic title, applied to a confederation of many nations at one time under the domination of one chief, whose power probably extended from the Alleghany mountains on the north to the shore of the Gulf; that it included tribes speaking a tongue closely akin to the Choktah is evident from the fragments we have remaining. This is further illustrated by a few words of “Appalachian,” preserved by John Chamberlayne.175 These, with their congeners in cognate dialects, are as follows:

The location of the tribe in after years is very uncertain. Dumont placed them in the northern part of what is now Alabama and Georgia, near the mountains that bear their name. That a portion of them did live in this vicinity is corroborated by the historians of South Carolina, who say that Colonel Moore, in 1703, found them “between the head-waters of the Savannah and Altamaha.”176 De l’Isle, also, locates them between the R. des Caouitas ou R. de Mai and the R. des Chaouanos ou d’Edisco, both represented as flowing nearly parallel from the mountains.

According to all the Spanish authorities on the other hand, they dwelt in the region of country between the Suwannee and Apalachicola rivers—yet must not be confounded with the Apalachicolos. Thus St. Marks was first named San Marco de Apalache, and it was near here that Narvaez and De Soto found them. They certainly had a large and prosperous town in this vicinity, said to contain a thousand warriors, whose chief was possessed of much influence.177 De l’Isle makes this their original locality, inscribing it “Icy estoient cy devant les Apalaches,” and their position in his day as one acquired subsequently. That they were driven from the Apalachicola by the Alibamons and other western tribes in 1705, does not admit of a doubt, yet it is equally certain that at the time of the cession of the country to the English, (1763,) they retained a small village near St. Marks, called San Juan.178 I am inclined to believe that these were different branches of the same confederacy, and the more so as we find a similar discrepancy in the earliest narratives of the French and Spanish explorers.

In the beginning of the eighteenth century they suffered much from the devastations of the English, French, and Creeks; indeed, it has been said, though erroneously, that the last remnant of their tribe “was totally destroyed by the Creeks in 1719.”179 About the time Spain regained possession of the soil, they migrated to the West and settled on the Bayou Rapide of Red River. Here they had a village numbering about fifty souls, and preserved for a time at least their native tongue, though using the French and Mobilian (Chikasah) for common purposes.180 Breckenridge,181 who saw them here, describes them as “wretched creatures, who are diminishing daily.” Probably by this time the last representative of this once powerful tribe has perished.

CHAPTER III.

PENINSULAR TRIBES OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

§ 1. Situation and Social Condition.—Caloosas.—Tegesta and Ais.—Tocobaga.—Vitachuco.—Utina.—Soturiba.—Method of Government.

§ 2. Civilization.—Appearance.—Games.—Agriculture.—Construction of Dwellings.—Clothing.

§ 3. Religion.—General Remarks.—Festivals in honor of the Sun and Moon.—Sacrifices.—Priests.—Sepulchral Rites.

§ 4. Languages.—Timuquana Tongue.—Words preserved by the French.

§ 1.—Situation and Social Condition

When in the sixteenth century the Europeans began to visit Florida they did not, as is asserted by the excellent bishop of Chiapa, meet with numerous well ordered and civilized nations,182 but on the contrary found the land sparsedly peopled by a barbarous and quarrelsome race of savages, rent asunder into manifold petty clans, with little peaceful leisure wherein to better their condition, wasting their lives in aimless and unending internecine war. Though we read of the cacique Vitachuco who opposed De Soto with ten thousand chosen warriors, of another who had four thousand always ready for battle,183 and other such instances of distinguished power, we must regard them as the hyperbole of men describing an unknown and strange land, supposed to abound in marvels of every description. The natural laws that regulate the increase of all hunting tribes, the analogy of other nations of equal civilization, the nature of the country, and lastly, the adverse testimony of these same writers, forbid us to entertain any other supposition. Including men, women, and children, the aboriginal population of the whole peninsula probably but little exceeded at any one time ten thousand souls. At the period of discovery these were parcelled out into villages, a number of which, uniting together for self-protection, recognized the authority of one chief. How many there were of these confederacies, or what were the precise limits of each, as they never were stable, so it is impossible to lay down otherwise than in very general terms, dependent as we are for our information on the superficial notices of military explorers, who took an interest in anything rather than the political relations of the nations they were destroying.

Commencing at the south, we find the extremity of the peninsula divided into two independent provinces, one called Tegesta on the shores of the Atlantic, the other and most important on the west or Gulf coast possessed by the Caloosa tribe.

The derivation of the name of the latter is uncertain. The French not distinguishing the final letter wrote it Calos and Callos; the Spaniards, in addition to making the same omission, softened the first vowel till the word sounded like Carlos, which is their usual orthography. This suggested to Barcia and others that the country was so called from the name of its chief, who, hearing from his Spanish captives the grandeur and power of Charles of Spain (Carlos V), in emulation appropriated to himself the title. Doubtless, however, it is a native word; and so Fontanedo, from whom we derive most of our knowledge of the province, and who was acquainted with the language, assures us. He translates it “village cruel,”184 an interpretation that does not enlighten us much, but which may refer to the exercise of the sovereign power. As a proper name, it may be the Muskohge charlo, trout, assumed, according to a common custom, by some individual. It is still preserved in the Seminole appellation of the Sanybal river, Carlosa-hatchie and Caloosa-hatchie, and in that of the bay of Carlos, corrupted by the English to Charlotte Harbor, both on the southwestern coast of the peninsula near north latitude 26° 40´.

According to Fontanedo, the province included fifty villages of thirty or forty inhabitants each, as follows: “Tampa, Tomo, Tuchi, Sogo, No which means beloved village, Sinapa, Sinaesta, Metamapo, Sacaspada, Calaobe, Estame, Yagua, Guayu, Guevu, Muspa, Casitoa, Tatesta, Coyovea, Jutun, Tequemapo, Comachica, Quisiyove, and two others; on Lake Mayaimi, Cutespa, Tavaguemme, Tomsobe, Enempa, and twenty others; in the Lucayan Isles, Guarunguve and Cuchiaga.” Some of these are plainly Spanish names, while others undoubtedly belong to the native tongue. Of these villages, Tampa has given its name to the inlet formerly called the bay of Espiritu Santo185 and to the small town at its head. Muspa was the name of a tribe of Indians who till the close of the last century inhabited the shores and islands in and near Boca Grande, where they are located on various old maps. Thence they were driven to the Keys and finally annihilated by the irruptions of the Seminoles and Spaniards.186 Guaragunve, or Guaragumbe, described by Fontanedo as the largest Indian village on Los Martires, and which means “the village of tears,” is probably a modified orthography of Matacumbe and identical with the island of Old Matacumbe, remarkable for the quantity of lignum vitæ there found,187 and one of the last refuges of the Muspa Indians. Lake Mayaimi, around which so many villages were situated, is identical with lake Okee-chobee, called on the older maps and indeed as late as Tanner’s and Carey’s, Myaco and Macaco. When Aviles ascended the St. Johns, he was told by the natives that it took its origin “from a great lake called Maimi thirty leagues in extent,” from which also streams flowed westerly to Carlos.188 In sound the word resembles the Seminole pai-okee or pai-hai-o-kee, grassy lake, the name applied with great fitness by this tribe to the Everglades.189 When travelling in Florida I found a small body of water near Manatee called lake Mayaco, and on the eastern shore the river Miami preserves the other form of the name.

The chief of the province dwelt in a village twelve or fourteen leagues from the southernmost cape.190 The earliest of whom we have any account, Sequene by name, ruled about the period of the discovery of the continent. During his reign Indians came from Cuba and Honduras, seeking the fountain of life. He was succeeded by Carlos, first of the name, who in turn was followed by his son Carlos. In the time of the latter, Francesco de Reinoso, under the command of Pedro Menendez de Aviles, the founder of St. Augustine and Adelantado of Florida, established a colony in this territory, which, however, owing to dissensions with the natives, never flourished, and finally the Cacique was put to death by Reinoso for some hostile demonstration. His son was taken by Aviles to Havana to be educated and there baptized Sebastian. Every attempt was made to conciliate him, and reconcile him to the Spanish supremacy but all in vain, as on his return he became “more troublesome and barbarous than ever.” This occurred about 1565-1575.191 Not long after his death the integrity of the state was destroyed, and splitting up into lesser tribes, each lived independent. They gradually diminished in number under the repeated attacks of the Spaniards on the south and their more warlike neighbors on the north. Vast numbers were carried into captivity by both, and at one period the Keys were completely depopulated. The last remnant of the tribe was finally cooped up on Cayo Vaco and Cayo Hueso (Key West), where they became notorious for their inhumanity to the unfortunate mariners wrecked on that dangerous reef. Ultimately, at the cession of Florida, to England in 1763, they migrated in a body to Cuba, to the number of eighty families, since which nothing is known of their fate.192

Of the province of Tegesta, situate to the west of the Caloosas, we have but few notices. It embraced a string of villages, the inhabitants of which were famed as expert fishers, (grandes Pescadores,) stretching from Cape Cañaveral to the southern extremity.193 The more northern portion was in later times called Ais, (Ays, Is) from the native word aïsa, deer, and by the Spaniards, who had a post here, Santa Lucea.194 The residence of the chief was near Cape Cañaveral, probably on Indian river, and not more than five days journey from the chief town of the Caloosas.

At the period of the French settlements, such amity existed between these neighbors, that the ruler of the latter sought in marriage the daughter of Oathcaqua, chief of Tegesta, a maiden of rare and renowned beauty. Her father, well aware how ticklish is the tenure of such a jewel, willingly granted the desire of his ally and friend. Encompassing her about with stalwart warriors, and with maidens not a few for her companions, he started to conduct her to her future spouse. But alas! for the anticipations of love! Near the middle of his route was a lake called Serrope, nigh five leagues about, encircling an island, whereon dwelt a race of men valorous in war and opulent from a traffic in dates, fruits, and a root “so excellent well fitted for bread, that you could not possibly eat better,” which formed the staple food of their neighbors for fifteen leagues around. These, fired by the reports of her beauty and the charms of the attendant maidens, waylay the party, rout the warriors, put the old father to flight, and carry off in triumph the princess and her fair escort, with them to share the joys and wonders of their island home.

Such is the romantic story told Laudonniére by a Spaniard long captive among the natives.195 Why seek to discredit it? May not Serrope be the beautiful Lake Ware in Marion county, which flows around a fertile central isle that lies like an emerald on its placid bosom, still remembered in tradition as the ancient residence of an Indian prince,196 and where relics of the red man still exist? The dates, les dattes, may have been the fruit of the Prunus Chicasaw, an exotic fruit known to have been cultivated by the later Indians, and the bread a preparation of the coonta root or the yam.

North of the province of Carlos, throughout the country around the Hillsboro river, and from it probably to the Withlacooche, and easterly to the Ocklawaha, all the tribes appear to have been under the domination of one ruler. The historians of De Soto’s expedition called the one in power at that period, Paracoxi, Hurripacuxi, and Urribarracuxi, names, however different in orthography, not unlike in sound, and which are doubtless corruptions of one and the same word, otherwise spelled Paracussi, and which was a generic appellation of the chiefs from Maryland to Florida. The town where they found him residing, is variously stated as twenty, twenty-five, and thirty leagues from the coast,197 and has by later writers been located on the head-waters of the Hillsboro river.198 In later times the cacique dwelt in a village on Old Tampa Bay, twenty leagues from the main, called Tocobaga or Togabaja,199 (whence the province derived its name,) and was reputed to be the most potent in Florida. A large mound still seen in the vicinity marks the spot.

This confederacy waged a desultory warfare with their southern neighbors. In 1567, Aviles, then superintending the construction of a fort among the Caloosas, resolved to establish a peace between them, and for this purpose went himself to Tocobaga. He there located a garrison, but the span of its existence was almost as brief as that of the peace he instituted. Subsequently, when the attention of the Spaniards became confined to their settlements on the eastern coast, they lost sight of this province, and thus no particulars of its after history are preserved.

The powerful chief Vitachuco, who is mentioned in the most extravagant terms by La Vega and the Gentleman of Elvas, seems, in connection with his two brothers, to have ruled over the rolling pine lands and broad fertile savannas now included in Marion and Alachua counties. Though his power is undoubtedly greatly over-estimated by these writers, we have reason to believe, both from existing remains and from the capabilities of the country, that this was the most densely populated portion of the peninsula, and that its possessors enjoyed a degree of civilization superior to that of the majority of their neighbors.

The chief Potavou mentioned in the French accounts, residing about twenty-five leagues, or two days’ journey from the territory of Utina, and at war with him, appears to have lived about the same spot, and may have been a successor or subject of the cacique of this province.200

The rich hammocks that border the upper St. Johns and the flat pine woods that stretch away on either side of this river, as far south as the latitude of Cape Cañaveral,201 were at the time of the first settlement of the country under the control of a chief called by the Spanish Utina, and more fully by the French Olata Ouæ Outina. His stationary residence was on the banks of the river near the northern extremity of Lake George, in which locality certain extensive earthworks are still found, probably referable to this period. So wide was his dominion that it was said to embrace more than forty subordinate chiefs,202 which, however, are to be understood only as the heads of so many single villages. It is remarkable, and not very easy of satisfactory explanation, that among nine of these mentioned by Laudonniére,203 two, Acquera and Moquoso, are the names of villages among the first encountered by De Soto in his march through the peninsula, and said by all the historians of the expedition to be subject to the chief Paracoxi.