полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 6 (of 9)

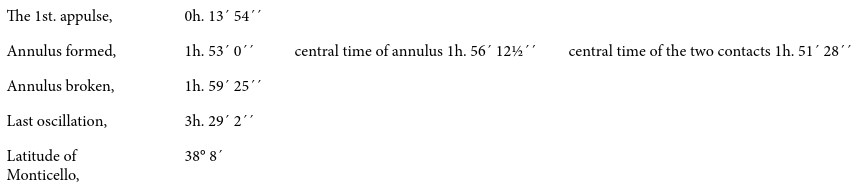

With respect to the eclipse of September 17. I know of no observations made in this State but my own, although I had no doubt that others had observed it. I used myself an equatorial telescope, and was aided by a friend who happened to be with me, and observed through an achromatic telescope of Dollard's. Two others attended the time-pieces. I had a perfect observation of the passage of the sun over the meridian, and the eclipse commencing but a few minutes after, left little room for error in our time. This little was corrected by the known rate of going of the clock. But we as good as lost the first appulse by a want of sufficiently early attention to be at our places, and composed. I have no confidence, therefore, by several seconds, in the time noted. The last oscillation of the two luminaries was better observed. Yet even there was a certain term of uncertainty as to the precise moment at which the indenture on the limb of the sun entirely vanished. It is therefore the forming of the annulus, and its breaking, which alone possess my entire and complete confidence. I am certain there was not an error of an instant of time in the observation of either of them. Their result therefore should not be suffered to be affected by either of the others. The four observations were as follows:

I have thus given you, Sir, my observations, with a candid statement of their imperfections. If they can be of any use to Mr. Bowditch, it will be more than was in view when they were made; and should I hear of any other observations made in this State, I shall not fail to procure and send him a copy of them. Be so good as to present me affectionately to your much-esteemed father, and to accept the tender of my respect.

TO MELATIAH NASH

Monticello, November 15, 1811.Sir,—I duly received your letter of October 24 on the publication of an Ephemeris. I have long thought it desirable that something of that kind should be published in the United States, holding a middle station between the nautical and the common popular almanacs. It would certainly be acceptable to a numerous and respectable description of our fellow citizens, who, without undertaking the higher astronomical operations, for which the former is calculated, yet occasionally wish for information beyond the scope of the common almanacs. What you propose to insert in your Ephemeris is very well so far. But I think you might give it more of the character desired by the addition of some other articles, which would not enlarge it more than a leaf or two. For instance, the equation of time is essential to the regulation of our clocks and watches, and would only add a narrow column to your 2d page. The sun's declination is often desirable, and would add but another narrow column to the same page. This last would be the more useful as an element for obtaining the rising and setting of the sun, in every part of the United States; for your Ephemeris will, I suppose, give it only for a particular parallel, as of New York, which would in a great measure restrain its circulation to that parallel. But the sun's declination would enable every one to calculate sunrise for himself, with scarcely more trouble than taking it from an Almanac. If you would add at the end of the work a formula for that calculation, as, for example, that for Delalande, § 1026, a little altered. Thus, to the Logarithmic tangent of the latitude (a constant number) add the Log. tangent of the sun's declination; taking 10 from the Index, the remainder is the line of an arch which, turned into time and added to 6 hours, gives sunrise for the winter half and sunset for the summer half of the year, to which may be added 3 lines only from the table of refractions, § 1028, or, to save even this trouble, and give the calculation ready made for every parallel, print a table of semi-diurnal arches, ranging the latitudes from 35° to 45° in a line at top and the degrees of declination in a vertical line on the left, and stating, in the line of the declination, the semi-diurnal arch for each degree of latitude, so that every one knowing the latitude of his place and the declination of the day, would find his sunrise or his sunset where their horizontal and vertical lines meet. This table is to be found in many astronomical books, as, for instance, in Wakeley's Mariner's Compass Rectified, and more accurately in the Connoissance des tems, for 1788. It would not occupy more than two pages at the end of the work, and would render it an almanac for every part of the United States.

To give novelty, and increase the appetite for continuing to buy your Ephemeris annually, you might every year select some one or two useful tables which many would wish to possess and preserve. These are to be found in the requisite tables, the Connoissance des tems for different years, and many in Pike's arithmetic.

I have given these hints because you requested my opinion. They may extend the plan of your Ephemeris beyond your view, which will be sufficient reason for not regarding them. In any event I shall willingly become a subscriber to it, if you should have any place of deposit for them in Virginia where the price can be paid. Accept the tender of my respects.

TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN RUSH

Poplar Forest, December 5, 1811.Dear Sir,—While at Monticello I am so much engrossed by business or society, that I can only write on matters of strong urgency. Here I have leisure, as I have everywhere the disposition to think of my friends. I recur, therefore, to the subject of your kind letters relating to Mr. Adams and myself, which a late occurrence has again presented to me. I communicated to you the correspondence which had parted Mrs. Adams and myself, in proof that I could not give friendship in exchange for such sentiments as she had recently taken up towards myself, and avowed and maintained in her letters to me. Nothing but a total renunciation of these could admit a reconciliation, and that could be cordial only in proportion as the return to ancient opinions was believed sincere. In these jaundiced sentiments of hers I had associated Mr. Adams, knowing the weight which her opinions had with him, and notwithstanding she declared in her letters that they were not communicated to him. A late incident has satisfied me that I wronged him as well as her, in not yielding entire confidence to this assurance on her part. Two of the Mr. * * * * *, my neighbors and friends, took a tour to the northward during the last summer. In Boston they fell into company with Mr. Adams, and by his invitation passed a day with him at Braintree. He spoke out to them everything which came uppermost, and as it occurred to his mind, without any reserve; and seemed most disposed to dwell on those things which happened during his own administration. He spoke of his masters, as he called his Heads of departments, as acting above his control, and often against his opinions. Among many other topics, he adverted to the unprincipled licentiousness of the press against myself, adding, "I always loved Jefferson, and still love him."

This is enough for me. I only needed this knowledge to revive towards him all the affections of the most cordial moments of our lives. Changing a single word only in Dr. Franklin's character of him, I knew him to be always an honest man, often a great one, but sometimes incorrect and precipitate in his judgments; and it is known to those who have ever heard me speak of Mr. Adams, that I have ever done him justice myself, and defended him when assailed by others, with the single exception as to political opinions. But with a man possessing so many other estimable qualities, why should we be dissocialized by mere differences of opinion in politics, in religion, in philosophy, or anything else. His opinions are as honestly formed as my own. Our different views of the same subject are the result of a difference in our organization and experience. I never withdrew from the society of any man on this account, although many have done it from me; much less should I do it from one with whom I had gone through, with hand and heart, so many trying scenes. I wish, therefore, but for an apposite occasion to express to Mr. Adams my unchanged affections for him. There is an awkwardness which hangs over the resuming a correspondence so long discontinued, unless something could arise which should call for a letter. Time and chance may perhaps generate such an occasion, of which I shall not be wanting in promptitude to avail myself. From this fusion of mutual affections, Mrs. Adams is of course separated. It will only be necessary that I never name her. In your letters to Mr. Adams, you can, perhaps, suggest my continued cordiality towards him, and knowing this, should an occasion of writing first present itself to him, he will perhaps avail himself of it, as I certainly will, should it first occur to me. No ground for jealousy now existing, he will certainly give fair play to the natural warmth of his heart. Perhaps I may open the way in some letter to my old friend Gerry, who I know is in habits of the greatest intimacy with him.

I have thus, my friend, laid open my heart to you, because you were so kind as to take an interest in healing again revolutionary affections, which have ceased in expression only, but not in their existence. God ever bless you, and preserve you in life and health.

TO DOCTOR CRAWFORD

Monticello, January 2, 1812.Sir,—Your favor of December 17th, has been duly received, and with it the pamphlet on the cause, seat and cure of diseases, for which be pleased to accept my thanks. The commencement which you propose by the natural history of the diseases of the human body, is a very interesting one, and will certainly be the best foundation for whatever relates to their cure. While surgery is seated in the temple of the exact sciences, medicine has scarcely entered its threshold. Her theories have passed in such rapid succession as to prove the insufficiency of all, and their fatal errors are recorded in the necrology of man. For some forms of disease, well known and well defined, she has found substances which will restore order to the human system, and it is to be hoped that observation and experience will add to their number. But a great mass of diseases remain undistinguished and unknown, exposed to the random shot of the theory of the day. If on this chaos you can throw such a beam of light as your celebrated brother has done on the sources of animal heat, you will, like him, render great service to mankind.

The fate of England, I think with you, is nearly decided, and the present form of her existence is drawing to a close. The ground, the houses, the men will remain; but in what new form they will revive and stand among nations, is beyond the reach of human foresight. We hope it may be one of which the predatory principle may not be the essential characteristic. If her transformation shall replace her under the laws of moral order, it is for the general interest that she should still be a sensible and independent weight in the scale of nations, and be able to contribute, when a favorable moment presents itself, to reduce under the same order, her great rival in flagitiousness. We especially ought to pray that the powers of Europe may be so poised and counterpoised among themselves, that their own safety may require the presence of all their force at home, leaving the other quarters of the globe in undisturbed tranquillity. When our strength will permit us to give the law of our hemisphere, it should be that the meridian of the mid-Atlantic should be the line of demarkation between war and peace, on this side of which no act of hostility should be committed, and the lion and the lamb lie down in peace together.

I am particularly thankful for the kind expressions of your letter towards myself, and tender you in return my best wishes and the assurances of my great respect and esteem.

TO MR. THOMAS PULLY

Monticello, January 8, 1812.Sir,—I have duly received your favor of December 22d, informing me that the society of artists of the United States had made me an honorary member of their society. I am very justly sensible of the honor they have done me, and I pray you to return them my thanks for this mark of their distinction. I fear that I can be but a very useless associate. Time, which withers the fancy, as the other faculties of the mind and body, presses on me with a heavy hand, and distance intercepts all personal intercourse. I can offer, therefore, but my zealous good wishes for the success of the institution, and that, embellishing with taste a country already overflowing with the useful productions, it may be able to give an innocent and pleasing direction to accumulations of wealth, which would otherwise be employed in the nourishment of coarse and vicious habits. With these I tender to the society and to yourself the assurances of my high respect and consideration.

TO COLONEL MONROE

Monticello, January 11, 1812.Dear Sir,—I thank you for your letter of the 6th. It is a proof of your friendship, and of the sincere interest you take in whatever concerns me. Of this I have never had a moment's doubt, and have ever valued it as a precious treasure. The question indeed whether I knew or approved of General Wilkinson's endeavors to prevent the restoration of the right of deposit at New Orleans, could never require a second of time to answer. But it requires some time for the mind to recover from the astonishment excited by the boldness of the suggestion. Indeed, it is with difficulty I can believe he has really made such an appeal; and the rather as the expression in your letter is that you have "casually heard it," without stating the degree of reliance which you have in the source of information. I think his understanding is above an expedient so momentary and so finally overwhelming. Were Dearborne and myself dead, it might find credit with some. But the world at large, even then, would weigh for themselves the dilemma, whether it was more probable that, in the situation I then was, clothed with the confidence and power of my country, I should descend to so unmeaning an act of treason, or that he, in the wreck now threatening him, should wildly lay hold of any plank. They would weigh his motives and views against those of Dearborne and myself, the tenor of his life against that of ours, his Spanish mysteries against my open cherishment of the Western interests; and, living as we are, and ready to purge ourselves by any ordeal, they must now weigh, in addition, our testimony against his. All this makes me believe he will never seek this refuge. I have ever and carefully restrained myself from the expression of any opinion respecting General Wilkinson, except in the case of Burr's conspiracy, wherein, after he had got over his first agitations, we believed his decision firm, and his conduct zealous for the defeat of the conspiracy, and although injudicious, yet meriting, from sound intentions, the support of the nation. As to the rest of his life, I have left it to his friends and his enemies, to whom it furnishes matter enough for disputation. I classed myself with neither, and least of all in this time of his distresses, should I be disposed to add to their pressure. I hope, therefore, he has not been so imprudent as to write our names in the pannel of his witnesses.

Accept the assurances of my constant affections.

TO JOHN ADAMS

Monticello, January 21, 1812.Dear Sir,—I thank you before hand (for they are not yet arrived) for the specimens of homespun you have been so kind as to forward me by post. I doubt not their excellence, knowing how far you are advanced in these things in your quarter. Here we do little in the fine way, but in coarse and middling goods a great deal. Every family in the country is a manufactory within itself, and is very generally able to make within itself all the stouter and middling stuffs for its own clothing and household use. We consider a sheep for every person in the family as sufficient to clothe it, in addition to the cotton, hemp and flax which we raise ourselves. For fine stuff we shall depend on your northern manufactories. Of these, that is to say, of company establishments, we have none. We use little machinery. The spinning jenny, and loom with the flying shuttle, can be managed in a family; but nothing more complicated. The economy and thriftiness resulting from our household manufactures are such that they will never again be laid aside; and nothing more salutary for us has ever happened than the British obstructions to our demands for their manufactures. Restore free intercourse when they will, their commerce with us will have totally changed its form, and the articles we shall in future want from them will not exceed their own consumption of our produce.

A letter from you calls up recollections very dear to my mind. It carries me back to the times when, beset with difficulties and dangers, we were fellow-laborers in the same cause, struggling for what is most valuable to man, his right of self-government. Laboring always at the same oar, with some wave ever ahead, threatening to overwhelm us, and yet passing harmless under our bark, we knew not how we rode through the storm with heart and hand, and made a happy port. Still we did not expect to be without rubs and difficulties; and we have had them. First, the detention of the western posts, then the coalition of Pilnitz, outlawing our commerce with France, and the British enforcement of the outlawry. In your day, French depredations; in mine, English, and the Berlin and Milan decrees; now, the English orders of council, and the piracies they authorize. When these shall be over, it will be the impressment of our seamen or something else; and so we have gone on, and so we shall go on, puzzled and prospering beyond example in the history of man. And I do believe we shall continue to growl, to multiply and prosper until we exhibit an association, powerful, wise and happy, beyond what has yet been seen by men. As for France and England, with all their preëminence in science, the one is a den of robbers, and the other of pirates. And if science produces no better fruits than tyranny, murder, rapine and destitution of national morality, I would rather wish our country to be ignorant, honest and estimable, as our neighboring savages are. But whither is senile garrulity leading me? Into politics, of which I have taken final leave. I think little of them and say less. I have given up newspapers in exchange for Tacitus and Thucydides, for Newton and Euclid, and I find myself much the happier. Sometimes, indeed, I look back to former occurrences, in remembrance of our old friends and fellow-laborers, who have fallen before us. Of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, I see now living not more than half a dozen on your side of the Potomac, and on this side, myself alone. You and I have been wonderfully spared, and myself with remarkable health, and a considerable activity of body and mind. I am on horseback three or four hours of every day; visit three or four times a year a possession I have ninety miles distant, performing the winter journey on horseback. I walk little, however, a single mile being too much for me, and I live in the midst of my grand children, one of whom has lately promoted me to be a great grandfather. I have heard with pleasure that you also retain good health, and a greater power of exercise in walking than I do. But I would rather have heard this from yourself, and that, writing a letter like mine, full of egotisms, and of details of your health, your habits, occupations and enjoyments, I should have the pleasure of knowing that in the race of life, you do not keep, in its physical decline, the same distance ahead of me which you have done in political honors and achievements. No circumstances have lessened the interest I feel in these particulars respecting yourself; none have suspended for one moment my sincere esteem for you, and I now salute you with unchanged affection and respect.

TO HIS EXCELLENCY GOVERNOR BARBOUR

Monticello, January 22, 1812.Dear Sir,—Your favor of the 14th has been duly received, and I sincerely congratulate you, or rather my country, on the just testimony of confidence which it has lately manifested to you. In your hands I know that its affairs will be ably and honestly administered.

In answer to your inquiry whether, in the early times of our government, where the council was divided, the practice was for the Governor to give the deciding vote? I must observe that, correctly speaking, the Governor not being a counsellor, his vote could make no part of an advice of council. That would be to place an advice on their journals which they did not give, and could not give because of their equal division. But he did what was equivalent in effect. While I was in the administration, no doubt was ever suggested that where the council, divided in opinion, could give no advice, the Governor was free and bound to act on his own opinion and his own responsibility. Had this been a change of the practice of my predecessor, Mr. Henry, the first governor, it would have produced some discussion, which it never did. Hence, I conclude it was the opinion and practice from the first institution of the government. During Arnold's and Cornwallis' invasion, the council dispersed to their several homes, to take care of their families. Before their separation, I obtained from them a capitulary of standing advices for my government in such cases as ordinarily occur: such as the appointment of militia officers, justices, inspectors, &c., on the recommendations of the courts; but in the numerous and extraordinary occurrences of an invasion, which could not be foreseen, I had to act on my own judgment and my own responsibility. The vote of general approbation, at the session of the succeeding winter, manifested the opinion of the Legislature, that my proceedings had been correct. General Nelson, my successor, staid mostly, I think, with the army; and I do not believe his council followed the camp, although my memory does not enable me to affirm the fact. Some petitions against him for impressment of property without authority of law, brought his proceedings before the next Legislature; the questions necessarily involved were whether necessity, without express law, could justify the impressment, and if it could, whether he could order it without the advice of council. The approbation of the Legislature amounted to a decision of both questions. I remember this case the more especially, because I was then a member of the Legislature, and was one of those who supported the Governor's proceedings, and I think there was no division of the House on the question. I believe the doubt was first suggested in Governor Harrison's time, by some member of the council, on an equal division. Harrison, in his dry way, observed that instead of one governor and eight counsellors, there would then be eight governors and one counsellor, and continued, as I understood, the practice of his predecessors. Indeed, it is difficult to suppose it could be the intention of those who framed the constitution, that when the council should be divided the government should stand still; and the more difficult as to a constitution formed during a war, and for the purpose of carrying on that war, that so high an officer as their Governor should be created and salaried, merely to act as the clerk and authenticator of the votes of the council. No doubt it was intended that the advice of the council should control the governor. But the action of the controlling power being withdrawn, his would be left free to proceed on its own responsibility. Where from division, absence, sickness or other obstacle, no advice could be given, they could not mean that their Governor, the person of their peculiar choice and confidence, should stand by, an inactive spectator, and let their government tumble to pieces for want of a will to direct it. In executive cases, where promptitude and decision are all important, an adherence to the letter of a law against its probable intentions, (for every law must intend that itself shall be executed,) would be fraught with incalculable danger. Judges may await further legislative explanations, but a delay of executive action might produce irretrievable ruin. The State is invaded, militia to be called out, an army marched, arms and provisions to be issued from the public magazines, the Legislature to be convened, and the council is divided. Can it be believed to have been the intention of the framers of the constitution, that the constitution itself and their constituents with it should be destroyed for want of a will to direct the resources they had provided for its preservation? Before such possible consequences all verbal scruples must vanish; construction must be made secundum arbitrium boni viri, and the constitution be rendered a practicable thing. That exposition of it must be vicious, which would leave the nation under the most dangerous emergencies without a directing will. The cautious maxims of the bench, to seek the will of the legislator and his words only, are proper and safer for judicial government. They act ever on an individual case only, the evil of which is partial, and gives time for correction. But an instant of delay in executive proceedings may be fatal to the whole nation. They must not, therefore, be laced up in the rules of the judiciary department. They must seek the intention of the legislator in all the circumstances which may indicate it in the history of the day, in the public discussions, in the general opinion and understanding, in reason and in practice. The three great departments having distinct functions to perform, must have distinct rules adapted to them. Each must act under its own rules, those of no one having any obligation on either of the others. When the opinion first begun that a governor could not act when his council could not or would not advise, I am uninformed. Probably not till after the war; for, had it prevailed then, no militia could have been opposed to Cornwallis, nor necessaries furnished to the opposing army of Lafayette. These, Sir, are my recollections and thoughts on the subject of your inquiry, to which I will only add the assurances of my great esteem and respect.