полная версия

полная версияThe Stones of Venice, Volume 2 (of 3)

§ XXIII. We have next to examine those features of the Gothic palaces in which the transitions of their architecture are most distinctly traceable; namely, the arches of the windows and doors.

It has already been repeatedly stated, that the Gothic style had formed itself completely on the mainland, while the Byzantines still retained their influence at Venice; and that the history of early Venetian Gothic is therefore not that of a school taking new forms independently of external influence, but the history of the struggle of the Byzantine manner with a contemporary style quite as perfectly organized as itself, and far more energetic. And this struggle is exhibited partly in the gradual change of the Byzantine architecture into other forms, and partly by isolated examples of genuine Gothic taken prisoner, as it were, in the contest; or rather entangled among the enemy’s forces, and maintaining their ground till their friends came up to sustain them. Let us first follow the steps of the gradual change, and then give some brief account of the various advanced guards and forlorn hopes of the Gothic attacking force.

XIV.

THE ORDERS OF VENETIAN ARCHES.

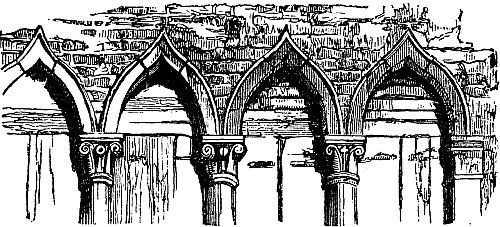

§ XXIV. The uppermost shaded series of six forms of windows in Plate XIV., opposite, represents, at a glance, the modifications of this feature in Venetian palaces, from the eleventh to the fifteenth century. Fig. 1 is Byzantine, of the eleventh and twelfth centuries; figs. 2 and 3 transitional, of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries; figs. 4 and 5 pure Gothic, of the thirteenth, fourteenth and early fifteenth; and fig. 6. late Gothic, of the fifteenth century, distinguished by its added finial. Fig. 4 is the longest-lived of all these forms: it occurs first in the thirteenth century; and, sustaining modifications only in its mouldings, is found also in the middle of the fifteenth.

I shall call these the six orders82 of Venetian windows, and when I speak of a window of the fourth, second, or sixth order, the reader will only have to refer to the numerals at the top of Plate XIV.

Then the series below shows the principal forms found in each period, belonging to each several order; except 1 b to 1 c, and the two lower series, numbered 7 to 16, which are types of Venetian doors.

§ XXV. We shall now be able, without any difficulty, to follow the course of transition, beginning with the first order, 1 and 1 a, in the second row. The horse-shoe arch, 1 b, is the door-head commonly associated with it, and the other three in the same row occur in St. Mark’s exclusively; 1 c being used in the nave, in order to give a greater appearance of lightness to its great lateral arcades, which at first the spectator supposes to be round-arched, but he is struck by a peculiar grace and elasticity in the curves for which he is unable to account, until he ascends into the galleries whence the true form of the arch is discernible. The other two—1 d, from the door of the southern transept, and 1 c, from that of the treasury,—sufficiently represent a group of fantastic forms derived from the Arabs, and of which the exquisite decoration is one of the most important features in St. Mark’s. Their form is indeed permitted merely to obtain more fantasy in the curves of this decoration.83 The reader can see in a moment, that, as pieces of masonry, or bearing arches, they are infirm or useless, and therefore never could be employed in any building in which dignity of structure was the primal object. It is just because structure is not the primal object in St. Mark’s, because it has no severe weights to bear, and much loveliness of marble and sculpture to exhibit, that they are therein allowable. They are of course, like the rest of the building, built of brick and faced with marble, and their inner masonry, which must be very ingenious, is therefore not discernible. They have settled a little, as might have been expected, and the consequence is, that there is in every one of them, except the upright arch of the treasury, a small fissure across the marble of the flanks.

Fig. XXVI.

§ XXVI. Though, however, the Venetian builders adopted these Arabian forms of arch where grace of ornamentation was their only purpose, they saw that such arrangements were unfit for ordinary work; and there is no instance, I believe, in Venice, of their having used any of them for a dwelling-house in the truly Byzantine period. But so soon as the Gothic influence began to be felt, and the pointed arch forced itself upon them, their first concession to its attack was the adoption, in preference to the round arch, of the form 3 a (Plate XIV., above); the point of the Gothic arch forcing itself up, as it were, through the top of the semicircle which it was soon to supersede.

§ XXVII. The woodcut above, Fig. XXVI., represents the door and two of the lateral windows of a house in the Corte del Remer, facing the Grand Canal, in the parish of the Apostoli. It is remarkable as having its great entrance on the first floor, attained by a bold flight of steps, sustained on pure pointed arches wrought in brick. I cannot tell if these arches are contemporary with the building, though it must always have had an access of the kind. The rest of its aspect is Byzantine, except only that the rich sculptures of its archivolt show in combats of animals, beneath the soffit, a beginning of the Gothic fire and energy. The moulding of its plinth is of a Gothic profile,84 and the windows are pointed, not with a reversed curve, but in a pure straight gable, very curiously contrasted with the delicate bending of the pieces of marble armor cut for the shoulders of each arch. There is a two-lighted window, such as that seen in the vignette, on each side of the door, sustained in the centre by a basket-worked Byzantine capital: the mode of covering the brick archivolt with marble, both in the windows and doorway, is precisely like that of the true Byzantine palaces.

Fig. XXVII.

§ XXVIII. But as, even on a small scale, these arches are weak, if executed in brickwork, the appearance of this sharp point in the outline was rapidly accompanied by a parallel change in the method of building; and instead of constructing the arch of brick and coating it with marble, the builders formed it of three pieces of hewn stone inserted in the wall, as in Fig. XXVII. Not, however, at first in this perfect form. The endeavor to reconcile the grace of the reversed arch with the strength of the round one, and still to build in brick, ended at first in conditions such as that represented at a, Fig. XXVIII., which is a window in the Calle del Pistor, close to the church of the Apostoli, a very interesting and perfect example. Here, observe, the poor round arch is still kept to do all the hard work, and the fantastic ogee takes its pleasure above, in the form of a moulding merely, a chain of bricks cast to the required curve. And this condition, translated into stone-work, becomes a window of the second order (b5, Fig. XXVIII., or 2, in Plate XIV.); a form perfectly strong and serviceable, and of immense importance in the transitional architecture of Venice.

Fig. XXVIII.

§ XXIX. At b, Fig. XXVIII., as above, is given one of the earliest and simplest occurrences of the second order window (in a double group, exactly like the brick transitional form a), from a most important fragment of a defaced house in the Salizzada San Liò, close to the Merceria. It is associated with a fine pointed brick arch, indisputably of contemporary work, towards the close of the thirteenth century, and it is shown to be later than the previous example, a, by the greater developement of its mouldings. The archivolt profile, indeed, is the simpler of the two, not having the sub-arch; as in the brick example; but the other mouldings are far more developed. Fig. XXIX. shows at 1 the arch profiles, at 2 the capital profiles, at 3 the basic-plinth profiles, of each window, a and b.

Fig. XXIX.

§ XXX. But the second order window soon attained nobler developement. At once simple, graceful, and strong, it was received into all the architecture of the period, and there is hardly a street in Venice which does not exhibit some important remains of palaces built with this form of window in many stories, and in numerous groups. The most extensive and perfect is one upon the Grand Canal in the parish of the Apostoli, near the Rialto, covered with rich decoration, in the Byzantine manner, between the windows of its first story; but not completely characteristic of the transitional period, because still retaining the dentil in the arch mouldings, while the transitional houses all have the simple roll. Of the fully established type, one of the most extensive and perfect examples is in a court in the Calle di Rimedio, close to the Ponte dell’ Angelo, near St. Mark’s Place. Another looks out upon a small square garden, one of the few visible in the centre of Venice, close by the Corte Salviati (the latter being known to every cicerone as that from which Bianca Capello fled). But, on the whole, the most interesting to the traveller is that of which I have given a vignette opposite.

But for this range of windows, the little piazza SS. Apostoli would be one of the least picturesque in Venice; to those, however, who seek it on foot, it becomes geographically interesting from the extraordinary involution of the alleys leading to it from the Rialto. In Venice, the straight road is usually by water, and the long road by land; but the difference of distance appears, in this case, altogether inexplicable. Twenty or thirty strokes of the oar will bring a gondola from the foot of the Rialto to that of the Ponte SS. Apostoli; but the unwise pedestrian, who has not noticed the white clue beneath his feet,85 may think himself fortunate, if, after a quarter of an hour’s wandering among the houses behind the Fondaco de’ Tedeschi, he finds himself anywhere in the neighborhood of the point he seeks. With much patience, however, and modest following of the guidance of the marble thread, he will at last emerge over a steep bridge into the open space of the Piazza, rendered cheerful in autumn by a perpetual market of pomegranates, and purple gourds, like enormous black figs; while the canal, at its extremity, is half-blocked up by barges laden with vast baskets of grapes as black as charcoal, thatched over with their own leaves.

Looking back, on the other side of this canal, he will see the windows represented in Plate XV., which, with the arcade of pointed arches beneath them, are the remains of the palace once belonging to the unhappy doge, Marino Faliero.

The balcony is, of course, modern, and the series of windows has been of greater extent, once terminated by a pilaster on the left hand, as well as on the right; but the terminal arches have been walled up. What remains, however, is enough, with its sculptured birds and dragons, to give the reader a very distinct idea of the second order window in its perfect form. The details of the capitals, and other minor portions, if these interest him, he will find given in the final Appendix.

XV.

WINDOWS OF THE SECOND ORDER.

CASA FALIER.

§ XXXI. The advance of the Gothic spirit was, for a few years, checked by this compromise between the round and pointed arch. The truce, however, was at last broken, in consequence of the discovery that the keystone would do duty quite as well in the form b as in the form a, Fig. XXX., and the substitution of b, at the head of the arch, gives us the window of the third order, 3 b, 3 d, and 3 e, in Plate XIV. The forms 3 a and 3 c are exceptional; the first occurring, as we have seen, in the Corte del Remer, and in one other palace on the Grand Canal, close to the Church of St. Eustachio; the second only, as far as I know, in one house on the Canna-Reggio, belonging to the true Gothic period. The other three examples, 3 b, 3 d, 3 e, are generally characteristic of the third order; and it will be observed that they differ not merely in mouldings, but in slope of sides, and this latter difference is by far the most material. For in the example 3 b there is hardly any true Gothic expression; it is still the pure Byzantine arch, with a point thrust up through it: but the moment the flanks slope, as in 3 d, the Gothic expression is definite, and the entire school of the architecture is changed.

Fig. XXX.

This slope of the flanks occurs, first, in so slight a degree as to be hardly perceptible, and gradually increases until, reaching the form 3 e at the close of the thirteenth century, the window is perfectly prepared for a transition into the fifth order.

§ XXXII. The most perfect examples of the third order in Venice are the windows of the ruined palace of Marco Querini, the father-in-law of Bajamonte Tiepolo, in consequence of whose conspiracy against the government this palace was ordered to be razed in 1310; but it was only partially ruined, and was afterwards used as the common shambles. The Venetians have now made a poultry market of the lower story (the shambles being removed to a suburb), and a prison of the upper, though it is one of the most important and interesting monuments in the city, and especially valuable as giving us a secure date for the central form of these very rare transitional windows. For, as it was the palace of the father-in-law of Bajamonte, and the latter was old enough to assume the leadership of a political faction in 1280,86 the date of the accession to the throne of the Doge Pietro Gradenigo, we are secure of this palace having been built not later than the middle of the thirteenth century. Another example, less refined in workmanship, but, if possible, still more interesting, owing to the variety of its capitals, remains in the little piazza opening to the Rialto, on the St. Mark’s side of the Grand Canal. The house faces the bridge, and its second story has been built in the thirteenth century, above a still earlier Byzantine cornice remaining, or perhaps introduced from some other ruined edifice, in the walls of the first floor. The windows of the second story are of pure third order; four of them are represented above, with their flanking pilaster, and capitals varying constantly in the form of the flower or leaf introduced between their volutes.

Fig. XXXI.

§ XXXIII. Another most important example exists in the lower story of the Casa Sagredo, on the Grand Canal, remarkable as having the early upright form (3 b, Plate XIV.) with a somewhat late moulding. Many others occur in the fragmentary ruins in the streets: but the two boldest conditions which I found in Venice are those of the Chapter-House of the Frari, in which the Doge Francesco Dandolo was buried circa 1339; and those of the flank of the Ducal Palace itself absolutely corresponding with those of the Frari, and therefore of inestimable value in determining the date of the palace. Of these more hereafter.

XVI.

WINDOWS OF THE FOURTH ORDER.

Fig. XXXII.

§ XXXIV. Contemporarily with these windows of the second and third orders, those of the fourth (4 a and 4 b, in Plate XIV.) occur, at first in pairs, and with simple mouldings, precisely similar to those of the second order, but much more rare, as in the example at the side, Fig. XXXII., from the Salizada San Liò; and then, enriching their mouldings as shown in the continuous series 4 c, 4 d, of Plate XIV., associate themselves with the fifth order windows of the perfect Gothic period. There is hardly a palace in Venice without some example, either early or late, of these fourth order windows; but the Plate opposite (XVI.) represents one of their purest groups at the close of the thirteenth century, from a house on the Grand Canal, nearly opposite the Church of the Scalzi. I have drawn it from the side, in order that the great depth of the arches may be seen, and the clear detaching of the shafts from the sheets of glass behind. The latter, as well as the balcony, are comparatively modern; but there is no doubt that if glass were used in the old window, it was set behind the shafts, at the same depth. The entire modification of the interiors of all the Venetian houses by recent work has however prevented me from entering into any inquiry as to the manner in which the ancient glazing was attached to the interiors of the windows.

The fourth order window is found in great richness and beauty at Verona, down to the latest Gothic times, as well as in the earliest, being then more frequent than any other form. It occurs, on a grand scale, in the old palace of the Scaligers, and profusely throughout the streets of the city. The series 4 a to 4 e, Plate XIV., shows its most ordinary conditions and changes of arch-line: 4 a and 4 b are the early Venetian forms; 4 c, later, is general at Venice; 4 d, the best and most piquant condition, owing to its fantastic and bold projection of cusp, is common to Venice and Verona; 4 e is early Veronese.

§ XXXV. The reader will see at once, in descending to the fifth row in Plate XIV., representing the windows of the fifth order, that they are nothing more than a combination of the third and fourth. By this union they become the nearest approximation to a perfect Gothic form which occurs characteristically at Venice; and we shall therefore pause on the threshold of this final change, to glance back upon, and gather together, those fragments of purer pointed architecture which were above noticed as the forlorn hopes of the Gothic assault.

Fig. XXXIII.

Fig. XXXIV.

The little Campiello San Rocco is entered by a sotto-portico behind the church of the Frari. Looking back, the upper traceries of the magnificent apse are seen towering above the irregular roofs and chimneys of the little square; and our lost Prout was enabled to bring the whole subject into an exquisitely picturesque composition, by the fortunate occurrence of four quaint trefoiled windows in one of the houses on the right. Those trefoils are among the most ancient efforts of Gothic art in Venice. I have given a rude sketch of them in Fig. XXXIII. They are built entirely of brick, except the central shaft and capital, which are of Istrian stone. Their structure is the simplest possible; the trefoils being cut out of the radiating bricks which form the pointed arch, and the edge or upper limit of that pointed arch indicated by a roll moulding formed of cast bricks, in length of about a foot, and ground at the bottom so as to meet in one, as in Fig. XXXIV. The capital of the shaft is one of the earliest transitional forms;87 and observe the curious following out, even in this minor instance, of the great law of centralization above explained with respect to the Byzantine palaces. There is a central shaft, a pilaster on each side, and then the wall. The pilaster has, by way of capital, a square flat brick, projecting a little, and cast, at the edge, into the form of the first type of all cornices (a, p. 63, Vol. I.; the reader ought to glance back at this passage, if he has forgotten it); and the shafts and pilasters all stand, without any added bases, on a projecting plinth of the same simple profile. These windows have been much defaced; but I have not the least doubt that their plinths are the original ones: and the whole group is one of the most valuable in Venice, as showing the way in which the humblest houses, in the noble times, followed out the system of the larger palaces, as far as they could, in their rude materials. It is not often that the dwellings of the lower orders are preserved to us from the thirteenth century.

XVII.

WINDOWS OF THE EARLY GOTHIC PALACES.

§ XXXVI. In the two upper lines of the opposite Plate (XVII.), I have arranged some of the more delicate and finished examples of Gothic work of this period. Of these, fig. 4 is taken from the outer arcade of San Fermo of Verona, to show the condition of mainland architecture, from which all these Venetian types were borrowed. This arch, together with the rest of the arcade, is wrought in fine stone, with a band of inlaid red brick, the whole chiselled and fitted with exquisite precision, all Venetian work being coarse in comparison. Throughout the streets of Verona, arches and windows of the thirteenth century are of continual occurrence, wrought, in this manner, with brick and stone; sometimes the brick alternating with the stones of the arch, as in the finished example given in Plate XIX. of the first volume, and there selected in preference to other examples of archivolt decoration, because furnishing a complete type of the master school from which the Venetian Gothic is derived.

§ XXXVII. The arch from St. Fermo, however, fig. 4, Plate XVII., corresponds more closely, in its entire simplicity, with the little windows from the Campiello San Rocco; and with the type 5 set beside it in Plate XVII., from a very ancient house in the Corte del Forno at Santa Marina (all in brick); while the upper examples, 1 and 2, show the use of the flat but highly enriched architrave, for the connection of which with Byzantine work see the final Appendix, Vol. III., under the head “Archivolt.” These windows (figs. 1 and 2, Plate XVII.) are from a narrow alley in a part of Venice now exclusively inhabited by the lower orders, close to the arsenal;88 they are entirely wrought in brick, with exquisite mouldings, not cast, but moulded in the clay by the hand, so that there is not one piece of the arch like another; the pilasters and shafts being, as usual, of stone.

§ XXXVIII. And here let me pause for a moment, to note what one should have thought was well enough known in England,—yet I could not perhaps touch upon anything less considered,—the real use of brick. Our fields of good clay were never given us to be made into oblong morsels of one size. They were given us that we might play with them, and that men who could not handle a chisel, might knead out of them some expression of human thought. In the ancient architecture of the clay districts of Italy, every possible adaptation of the material is found exemplified: from the coarsest and most brittle kinds, used in the mass of the structure, to bricks for arches and plinths, cast in the most perfect curves, and of almost every size, strength, and hardness; and moulded bricks, wrought into flower-work and tracery as fine as raised patterns upon china. And, just as many of the finest works of the Italian sculptors were executed in porcelain, many of the best thoughts of their architects are expressed in brick, or in the softer material of terra cotta; and if this were so in Italy, where there is not one city from whose towers we may not descry the blue outline of Alp or Apennine, everlasting quarries of granite or marble, how much more ought it to be so among the fields of England! I believe that the best academy for her architects, for some half century to come, would be the brick-field; for of this they may rest assured, that till they know how to use clay, they will never know how to use marble.