полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

10. Birth customs.

Among the Rāwats of Chhattīsgarh, when a child is shortly to be born the midwife dips her hand in oil and presses it on the wall, and it is supposed that she can tell by the way in which the oil trickles down whether the child will be a boy or a girl. If a woman is weak and ill during her pregnancy it is thought that a boy will be born, but if she is strong and healthy, a girl. A woman in advanced pregnancy is given whatever she desires to eat, and on one occasion especially delicate kinds of food are served to her, this rite being known as Sidhori. The explanation of the custom is that if the mother does not get the food she desires during pregnancy the child will long for it all through life. If delivery is delayed, a line of men and boys is sometimes made from the door of the house to a well, and a vessel is then passed from hand to hand from the house, filled with water, and back again. Thus the water, having acquired the quality of speed during its rapid transit, will communicate this to the woman and cause her quick delivery. Or they take some of the clay left unmoulded on the potter’s wheel and give it her to drink in water; the explanation of this is exactly similar, the earth having acquired the quality of swiftness by the rapid transit on the wheel. If three boys or three girls have been born to a woman, they think that the fourth should be of the same sex, in order to make up two pairs. A boy or girl born after three of the opposite sex is called Titra or Titri, and is considered very unlucky. To avert this misfortune they cover the child with a basket, kindle a fire of grass all round it, and smash a brass pot on the floor. Then they say that the baby is the fifth and not the fourth child, and the evil is thus removed. When one woman gives birth to a male and another to a female child in the same quarter of a village on the same day and they are attended by the same midwife, it is thought that the boy child will fall ill from the contagion of the girl child communicated through the midwife. To avoid this, on the following Sunday the child’s maternal uncle makes a banghy, which is carried across the shoulders like a large pair of scales, and weighs the child in it against cowdung. He then takes the banghy and deposits it at cross-roads outside the village. The father cannot see either the child or its mother till after the Chathi or sixth-day ceremony of purification, when the mother is bathed and dressed in clean clothes, the males of the family are shaved, all their clothes are washed, and the house is whitewashed; the child is also named on this day. The mother cannot go out of doors until after the Bārhi or twelfth-day ceremony. If a child is born at an unlucky astrological period its ears are pierced in the fifth month after birth as a means of protection.

Image of Krishna as Murlidhar or the flute-player, with attendant deities.

11. Funeral rites. Bringing back the soul.

The dead are either buried or burnt. When a man is dying they put basil leaves and boiled rice and milk in his mouth, and a little piece of gold, or if they have not got gold they put a rupee in his mouth and take it out again. For ten days after a death, food in a leaf-cup and a lamp are set out in the house-yard every evening, and every morning water and a tooth-stick. On the tenth day they are taken away and consigned to a river. In Chhattīsgarh on the third day after death the soul is brought back. The women put a lamp on a red earthen pot and go to a tank or stream at night. The fish are attracted towards the light, and one of them is caught and put in the pot, which is then filled with water. It is brought home and set beside a small heap of flour, and the elders sit round it. The son of the deceased or other near relative anoints himself with turmeric and picks up a stone. This is washed with the water from the pot, and placed on the floor, and a sacrifice of a cock or hen is made to it according as the deceased was a man or a woman. The stone is then enshrined in the house as a family god, and the sacrifice of a fowl is repeated annually. It is supposed apparently that the dead man’s spirit is brought back to the house in the fish, and then transferred to the stone by washing this with the water.

12. Religion. Krishna and other deified cowherds.

The Ahīrs have a special relation to the Hindu religion, owing to their association with the sacred cow, which is itself revered as a goddess. When religion gets to the anthropomorphic stage the cowherd, who partakes of the cow’s sanctity, may be deified as its representative. This was probably the case with Krishna, one of the most popular gods of Hinduism, who was a cowherd, and, as he is represented as being of a dark colour, may even have been held to be of the indigenous races. Though, according to the legend, he was really of royal birth, Krishna was brought up by Nānd, a herdsman of Gokul, and Jasoda or Dasoda his wife, and in the popular belief these are his parents, as they probably were in the original story. The substitution of Krishna, born as a prince, for Jasoda’s daughter, in order to protect him from destruction by the evil king Kānsa of Mathura, is perhaps a later gloss, devised when his herdsman parentage was considered too obscure for the divine hero. Krishna’s childhood in Jasoda’s house with his miraculous feats of strength and his amorous sports with Rādha and the other milkmaids of Brindāwan, are among the most favourite Hindu legends. Govind and Gopāl, the protector or guardian of cows, are names of Krishna and the commonest names of Hindus, as are also his other epithets, Murlidhar and Bansidhar, the flute-player; for Krishna and Balārām, like Greek and Roman shepherds, were accustomed to divert themselves with song, to the accompaniment of the same instrument. The child Krishna is also very popular, and his birthday, the Janam-Ashtami on the 8th of dark Bhādon (August), is a great festival. On this day potsful of curds are sprinkled over the assembled worshippers. Krishna, however, is not the solitary instance of the divine cowherd, but has several companions, humble indeed compared to him, but perhaps owing their apotheosis to the same reasons. Bhīlat, a popular local godling of the Nerbudda Valley, was the son of an Ahīr or Gaoli woman; she was childless and prayed to Pārvati for a child, and the goddess caused her votary to have one by her own husband, the god Mahādeo. Bhīlat was stolen away from his home by Mahādeo in the disguise of a beggar, and grew up to be a great hero and made many conquests; but finally he returned and lived with his herdsman parents, who were no doubt his real ones. He performed numerous miracles, and his devotees are still possessed by his spirit. Singāji is another godling who was a Gaoli by caste in Indore. He became a disciple of a holy Gokulastha Gosain or ascetic, and consequently a great observer of the Janam-Ashtami or Krishna’s birthday.26 On one occasion Singāji was late for prayers on this day, and the guru was very angry, and said to him, ‘Don’t show your face to me again until you are dead.’ Singāji went home and told the other children he was going to die. Then he went and buried himself alive. The occurrence was noised abroad and came to the ears of the guru, who was much distressed, and proceeded to offer his condolences to Singāji’s family. But on the way he saw Singāji, who had been miraculously raised from the dead on account of his virtuous act of obedience, grazing his buffaloes as before. After asking for milk, which Singāji drew from a male buffalo calf, the guru was able to inform the bereaved parents of their son’s joyful reappearance and his miraculous powers; of these Singāji gave further subsequent demonstration, and since his death, said to have occurred 350 years ago, is widely venerated. The Gaolis pray to him for the protection of their cattle from disease, and make thank-offerings of butter if these prayers are fulfilled. Other pilgrims to Singāji’s shrine offer unripe mangoes and sugar, and an annual fair is held at it, when it is said that for seven days no cows, flies or ants are to be seen in the place. In the Betūl district there is a village godling called Dait, represented by a stone under a tree. He is the spirit of any Ahīr who in his lifetime was credited in the locality with having the powers of an exorcist. In Mandla and other Districts when any buffalo herdsman dies at a very advanced age the people make a platform for him within the village and call it Mahashi Deo or the buffalo god. Similarly, when an old cattle herdsman dies they do the same, and call it Balki Deo or the bullock god. Here we have a clear instance of the process of substituting the spirit of the herdsman for the cow or buffalo as an object of worship. The occupation of the Ahīr also lends itself to religious imaginations. He stays in the forest or waste grass-land, frequently alone from morning till night, watching his herds; and the credulous and uneducated minds of the more emotional may easily hear the voices of spirits, or in a half-sleeping condition during the heat and stillness of the long day may think that visions have appeared to them. Thus they come to believe themselves selected for communication with the unseen deities or spirits, and on occasions of strong religious excitement work themselves into a frenzy and are held to be possessed by a spirit or god.

13. Caste deities.

Among the special deities of the Ahīrs is Kharak Deo, who is always located at the khirkha, or place of assembly of the cattle, on going to and returning from pasture. He appears to be the spirit or god of the khirkha. He is represented by a platform with an image of a horse on it, and when cattle fall ill the owners offer flour and butter to him. These are taken by the Ahīrs in charge, and it is thought that the cattle will get well. Matar Deo is the god of the pen or enclosure for cattle made in the jungle. Three days after the Diwāli festival the Rāwats sacrifice one or more goats to him, cutting off their heads. They throw the heads into the air, and the cattle, smelling the blood, run together and toss them with their horns as they do when they scent a tiger. The men then say that the animals are possessed by Matar Deo. Guraya Deo is a deity who lives in the cattle-stalls in the village and is worshipped once a year. A man holds an egg in his hand, and walks round the stall pouring liquid over the egg all the way, so as to make a line round it. The egg is then buried beneath the shrine of the god, the rite being probably meant to ensure his aid for the protection of the cattle from disease in their stalls. A favourite saint of the Ahīrs is Haridās Bāba. He was a Jogi, and could separate his soul from his body at pleasure. On one occasion he had gone in spirit to Benāres, leaving his body in the house of one of his disciples, who was an Ahīr. When he did not return, and the people heard that a dead body was lying there, they came and insisted that it should be burnt. When he came back and found that his body was burnt, he entered into a man and spoke through him, telling the people what had happened. In atonement for their unfortunate mistake they promised to worship him.

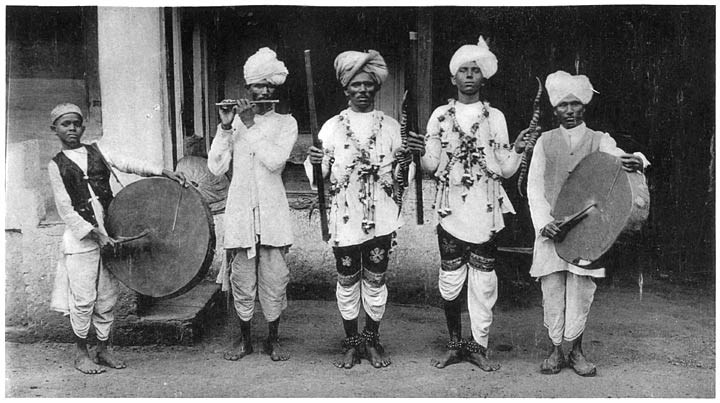

Ahīr dancers in Diwāli costume.

14. Other deities.

The Mahākul Ahīrs of Jashpur have three deities, whom they call Mahādeo or Siva, Sahādeo, one of the five Pāndava brothers, and the goddess Lakshmi. They say that the buffalo is Mahādeo, the cow Sahādeo, and the rice Lakshmi. This also appears to be an instance of the personification of animals and the corn into anthropomorphic deities.

15. The Diwāli festival.

The principal festival of the Ahīrs is the Diwāli, falling about the beginning of November, which is also the time when the autumn crops ripen. All classes observe this feast by illuminating their houses with many small saucer-lamps and letting off crackers and fireworks, and they generally gamble with money to bring them good luck during the coming year. The Ahīrs make a mound of earth, which is called Govardhan, that is the mountain in Mathura which Krishna held upside down on his finger for seven days and nights, so that all the people might gather under it and be protected from the devastating storms of rain sent by Indra. After dancing round the mound they drive their cattle over it and make them trample it to pieces. At this time a festival called Marhai is held, at which much liquor is drunk and all classes disport themselves. In Damoh on this day the Ahīrs go to the standing-place for village cattle, and after worshipping the god, frighten the cattle by waving leaves of the basil-plant at them, and then put on fantastic dresses, decorating themselves with cowries, and go round the village, singing and dancing. Elsewhere at the time of the Marhai they dance round a pole with peacock feathers tied to the top, and sometimes wear peacock feathers themselves, as well as aprons sewn all over with cowries. It is said that Krishna and Balārām used to wear peacock feathers when they danced in the jungles of Mathura, but this rite has probably some connection with the worship of the peacock. This bird might be venerated by the Ahīrs as one of the prominent denizens of the jungle. In Raipur they tie a white cock to the top of the pole and dance round it. In Mandla, Khila Mutha, the god of the threshing-floor, is worshipped at this time, with offerings of a fowl and a goat. They also perform the rite of jagāna or waking him up. They tie branches of a small shrub to a stick and pour milk over the stone which is his emblem, and sing, ‘Wake up, Khila Mutha, this is the night of Amāwas’ (the new moon). Then they go to the cattle-shed and wake up the cattle, crying, ‘Poraiya, god of the door, watchman of the window, open the door, Nānd Gowāl is coming.’ Then they drive out the cattle and chase them with the branches tied to their sticks as far as their grazing-ground. Nānd Gowāl was the foster-father of Krishna, and is now said to signify a man who has a lakh (100,000) of cows. This custom of frightening the cattle and making them run is called dhor jagāna or bichkāna, that is, to wake up or terrify the cattle. Its meaning is obscure, but it is said to preserve the cattle from disease during the year. In Raipur the women make an image of a parrot in clay at the Diwāli and place it on a pole and go round to the different houses, singing and dancing round the pole, and receiving presents of rice and money. They praise the parrot as the bird who carries messages from a lover to his mistress, and as living on the mountains and among the green verdure, and sing:

“Oh, parrot, where shall we sow gondla grass and where shall we sow rice?

“We will sow gondla in a pond and rice in the field.

“With what shall we cut gondla grass, and with what shall we cut rice?

“We shall cut gondla with an axe and rice with a sickle.”

It is probable that the parrot is revered as a spirit of the forest, and also perhaps because it is destructive to the corn. The parrot is not, so far as is known, associated with any god, but the Hindus do not kill it. In Bilāspur an ear of rice is put into the parrot’s mouth, and it is said there that the object of the rite is to prevent the parrots from preying on the corn.

16. Omens.

On the night of the full moon of Jesth (May) the Ahīrs stay awake all night, and if the moon is covered with clouds they think that the rains will be good. If a cow’s horns are not firmly fixed in the head and seem to shake slightly, it is called Maini, and such an animal is considered to be lucky. If a bullock sits down with three legs under him and the fourth stretched out in front it is a very good omen, and it is thought that his master’s cattle will increase and multiply. When a buffalo-calf is born they cover it at once with a black cloth and remove it from the mother’s sight, as they think that if she saw the calf and it then died her milk would dry up. The calf is fed by hand. Cow-calves, on the other hand, are usually left with the mother, and many people allow them to take all the milk, as they think it a sin to deprive them of it.

17. Social customs.

The Ahīrs will eat the flesh of goats and chickens, and most of them consume liquor freely. The Kaonra Ahīrs of Mandla eat pork, and the Rāwats of Chhattīsgarh are said not to object to field-mice and rats, even when caught in the houses. The Kaonra Ahīrs are also said not to consider a woman impure during the period of menstruation. Nevertheless the Ahīrs enjoy a good social status, owing to their relations with the sacred cow. As remarked by Eha: “His family having been connected for many generations with the sacred animal he enjoys a certain consciousness of moral respectability, like a man whose uncles are deans or canons.”27 All castes will take water from the hands of an Ahīr, and in Chhattīsgarh and the Uriya country the Rāwats and Gahras, as the Ahīr caste is known respectively in these localities, are the only caste from whom Brāhmans and all other Hindus will take water. On this account, and because of their comparative purity, they are largely employed as personal servants. In Chhattīsgarh the ordinary Rāwats will clean the cooking-vessels even of Muhammadans, but the Thethwār or pure Rāwats refuse this menial work. In Mandla, when a man is to be brought back into caste after a serious offence, such as getting vermin in a wound, he is made to stand in the middle of a stream, while some elderly relative pours water over him. He then addresses the members of the caste panchāyat or committee, who are standing on the bank, saying to them, ‘Will you leave me in the mud or will you take me out?’ Then they tell him to come out, and he has to give a feast. At this a member of the Meliha sept first eats food and puts some into the offender’s mouth, thus taking the latter’s sin upon himself. The offender then addresses the panchāyat saying, ‘Rājas of the Panch, eat.’ Then the panchāyat and all the caste take food with him and he is readmitted. In Nāndgaon State the head of the caste panchāyat is known as Thethwār, the title of the highest subcaste, and is appointed by the Rāja, to whom he makes a present. In Jashpur, among the Mahākul Ahīrs, when an offender is put out of caste he has on readmission to make an offering of Rs. 1–4 to Bālāji, the tutelary deity of the State. These Mahākuls desire to be considered superior to ordinary Ahīrs, and their social rules are hence very strict. A man is put out of caste if a dog, fowl or pig touches his water or cooking-pots, or if he touches a fowl. In the latter case he is obliged to make an offering of a fowl to the local god, and eight days are allowed for procuring it. A man is also put out of caste for beating his father. In Mandla, Ahīrs commonly have the title of Patel or headman of a village, probably because in former times, when the country consisted almost entirely of forest and grass land, they were accustomed to hold large areas on contract for grazing.

18. Ornaments.

In Chhattīsgarh the Rāwat women are especially fond of wearing large churas or leg-ornaments of bell-metal. These consist of a long cylinder which fits closely to the leg, being made in two halves which lock into each other, while at each end and in the centre circular plates project outwards horizontally. A pair of these churas may weigh 8 or 10 lbs., and cost from Rs. 3 to Rs. 9. It is probable that some important magical advantage was expected to come from the wearing of these heavy appendages, which must greatly impede free progression, but its nature is not known.

19. Occupation.

Only about thirty per cent of the Ahīrs are still occupied in breeding cattle and dealing in milk and butter. About four per cent are domestic servants, and nearly all the remainder cultivators and labourers. In former times the Ahīrs had the exclusive right of milking the cow, so that on all occasions an Ahīr must be hired for this purpose even by the lowest castes. Any one could, however, milk the buffalo, and also make curds and other preparations from cow’s milk.28 This rule is interesting as showing how the caste system was maintained and perpetuated by the custom of preserving to each caste a monopoly of its traditional occupation. The rule probably applied also to the bulk of the cultivating and the menial and artisan castes, and now that it has been entirely abrogated it would appear that the gradual decay and dissolution of the caste organisation must follow. The village cattle are usually entrusted jointly to one or more herdsmen for grazing purposes. The grazier is paid separately for each animal entrusted to his care, a common rate being one anna for a cow or bullock and two annas for a buffalo per month. When a calf is born he gets four annas for a cow-calf and eight annas for a she-buffalo, but except in the rice districts nothing for a male buffalo-calf, as these animals are considered useless outside the rice area. The reason is that buffaloes do not work steadily except in swampy or wet ground, where they can refresh themselves by frequent drinking. In the northern Districts male buffalo-calves are often neglected and allowed to die, but the cow-buffaloes are extremely valuable, because their milk is the principal source of supply of ghī or boiled butter. When a cow or buffalo is in milk the grazier often gets the milk one day out of four or five. When a calf is born the teats of the cow are first milked about twenty times on to the ground in the name of the local god of the Ahīrs. The remainder of the first day’s milk is taken by the grazier, and for the next few days it is given to friends. The village grazier is often also expected to prepare the guest-house for Government officers and others visiting the village, fetch grass for their animals, and clean their cooking vessels. For this he sometimes receives a small plot of land and a present of a blanket annually from the village proprietor. Mālguzārs and large tenants have their private herdsmen. The pasturage afforded by the village waste lands and forest is, as a rule, only sufficient for the plough-bullocks and more valuable milch-animals. The remainder are taken away sometimes for long distances to the Government forest reserves, and here the herdsmen make stockades in the jungle and remain there with their animals for months together. The cattle which remain in the village are taken by the owners in the early morning to the khirkha or central standing-ground. Here the grazier takes them over and drives them out to pasture. He brings them back at ten or eleven, and perhaps lets them stand in some field which the owner wants manured. Then he separates the cows and milch-buffaloes and takes them to their masters’ houses, where he milks them all. In the afternoon all the cattle are again collected and driven out to pasture. The cultivators are very much in the grazier’s hands, as they cannot supervise him, and if dishonest he may sell off a cow or calf to a friend in a distant village and tell the owner that it has been carried off by a tiger or panther. Unless the owner succeeds by a protracted search or by accident in finding the animal he cannot disprove the herdsman’s statement, and the only remedy is to dispense with the latter’s services if such losses become unduly frequent. On this account, according to the proverbs, the Ahīr is held to be treacherous and false to his engagements. They are also regarded as stupid because they seldom get any education, retain their rustic and half-aboriginal dialect, and on account of their solitary life are dull and slow-witted in company. ‘The barber’s son learns to shave on the Ahīr’s head.’ ‘The cow is in league with the milkman and lets him milk water into the pail.’ The Ahīrs are also hot-tempered, and their propensity for drinking often results in affrays, when they break each other’s head with their cattle-staffs. ‘A Gaoli’s quarrel: drunk at night and friends in the morning.’

20. Preparations of milk.

Hindus nearly always boil their milk before using it, as the taste of milk fresh from the cow is considered unpalatable. After boiling, the milk is put in a pot and a little old curds added, when the whole becomes dahi or sour curds. This is a favourite food, and appears to be exactly the same substance as the Bulgarian sour milk which is now considered to have much medicinal value. Butter is also made by churning these curds or dahi. Butter is never used without being boiled first, when it becomes converted into a sort of oil; this has the advantage of keeping much better than fresh butter, and may remain fit for use for as long as a year. This boiled butter is known as ghī, and is the staple product of the dairy industry, the bulk of the surplus supply of milk being devoted to its manufacture. It is freely used by all classes who can afford it, and serves very well for cooking purposes. There is a comparatively small market for fresh milk among the Hindus, and as a rule only those drink milk who obtain it from their own animals. The acid residue after butter has been made from dahi (curds) or milk is known as matha or butter-milk, and is the only kind of milk drunk by the poorer classes. Milk boiled so long as to become solidified is known as khīr, and is used by confectioners for making sweets. When the milk is boiled and some sour milk added to it, so that it coagulates while hot, the preparation is called chhana. The whey is expressed from this by squeezing it in a cloth, and a kind of cheese is obtained.29 The liquid which oozes out at the root of a cow’s horns after death is known as gaolochan and sells for a high price, as it is considered a valuable medicine for children’s cough and lung diseases.