полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

6. Religion and magic.

The Bharias call themselves Hindus and worship the village deities of the locality, and on the day of Diwāli offer a black chicken to their family god, who may be Bura Deo, Dūlha Deo or Karua, the cobra. For this snake they profess great reverence, and say that he was actually born in a Bharia family. As he could not work in the fields he was usually employed on errands. One day he was sent to the house, and surprised one of his younger brother’s wives, who had not heard him coming, without her veil. She reproached him, and he retired in dudgeon to the oven, where he was presently burnt to death by another woman, who kindled a fire under it not knowing that he was there. So he has been deified and is worshipped by the tribe. The Bharias also venerate Bāgheshwar, the tiger god, and believe that no tiger will eat a Bharia. On the Diwāli day they invite the tiger to drink some gruel which they place ready for him behind their houses, at the same time warning the other villagers not to stir out of doors. In the morning they display the empty vessels as a proof that the tiger has visited them. They practise various magical devices, believing that they can kill a man by discharging at him a mūth or handful of charmed objects such as lemons, vermilion and seeds of urad. This ball will travel through the air and, descending on the house of the person at whom it is aimed, will kill him outright unless he can avert its power by stronger magic, and perhaps even cause it to recoil in the same manner on the head of the sender. They exorcise the Sudhiniyas or the drinkers of human blood. A person troubled by one of these is seated near the Bharia, who places two pots with their mouths joined over a fire. He recites incantations and the pots begin to boil, emitting blood. This result is obtained by placing a herb in the pot whose juice stains the water red. The blood-sucker is thus successfully exorcised. To drive away the evil eye they burn a mixture of chillies, salt, human hair and the husks of kodon, which emits a very evil smell. Such devices are practised by members of the tribe who hold the office of Bhumia or village priest. The Bharias are well-known thieves, and they say that the dark spots on the moon are caused by a banyan tree, which God planted with the object of diminishing her light and giving thieves a chance to ply their trade. If a Bhumia wishes to detect a thief, he sits clasping hands with a friend, while a pitcher is supported on their hands. An oblation is offered to the deity to guide the ordeal correctly, and the names of suspected persons are recited one by one, the name at which the pitcher topples over being that of the thief. But before employing this method of detection the Bhumia proclaims his intention of doing so on a certain date, and in the meantime places a heap of ashes in some lonely place and invites the thief to deposit the stolen article in the ashes to save himself from exposure. By common custom each person in the village is required to visit the heap and mingle a handful of ashes with it, and not infrequently the thief, frightened at the Bhumia’s powers of detection, takes the stolen article and buries it in the ash-heap where it is duly found, the necessity for resorting to the further method of divination being thus obviated. Occasionally the Bharia in his character of a Hindu will make a vow to pay for a recitation of the Satya Nārāyan Katha or some other holy work. But he understands nothing of it, and if the Brāhman employed takes a longer time than he had bargained for over the recitation he becomes extremely bored and irritated.

7. Social life and customs.

The scantiness of the Bharia’s dress is proverbial, and the saying is ‘Bharia bhwāka, pwānda langwāta’, or ‘The Bharia is verily a devil, who only covers his loins with a strip of cloth.’ But lately he has assumed more clothing. Formerly an iron ring carried on the wrist to exorcise the evil spirits was his only ornament. Women wear usually only one coarse cloth dyed red, spangles on the forehead and ears, bead necklaces, and cheap metal bracelets and anklets. Some now have Hindu ornaments, but in common with other low castes they do not usually wear a nose-ring, out of respect to the higher castes. Women, though they work in the fields, do not commonly wear shoes; and if these are necessary to protect the feet from thorns, they take them off and carry them in the presence of an elder or a man of higher caste. They are tattooed with various devices, as a cock, a crown, a native chair, a pitcher stand, a sieve and a figure called dhandha, which consists of six dots joined by lines, and appears to be a representation of a man, one dot standing for the head, one for the body, two for the arms and two for the legs. This device is also used by other castes, and they evince reluctance if asked to explain its meaning, so that it may be intended as a representation of the girl’s future husband. The Bharia is considered very ugly, and a saying about him is: ‘The Bharia came down from the hills and got burnt by a cinder, so that his face is black.’ He does not bathe for months together, and lives in a dirty hovel, infested by the fowls which he loves to rear. His food consists of coarse grain, often with boiled leaves as a vegetable, and he consumes much whey, mixing it with his scanty portion of grain. Members of all except the lowest castes are admitted to the Bharia community on presentation of a pagri and some money to the headman, together with a feast to the caste-fellows. The Bharias do not eat monkeys, beef or the leavings of others, but they freely consume fowls and pork. They are not considered as impure, but rank above those castes only whose touch conveys pollution. For the slaughter of a cow the Bilāspur Bharias inflict the severe punishment of nine daily feasts to the caste, or one for each limb of the cow, the limbs being held to consist of the legs, ears, horns and tail. They have an aversion for the horse and will not remove its dung. To account for this they tell a story to the effect that in the beginning God gave them a horse to ride and fight upon. But they did not know how to mount the horse because it was so high. The wisest man among them then proposed to cut notches in the side of the animal by which they could climb up, and they did this. But God, when he saw it, was very angry with them, and ordered that they should never be soldiers, but should be given a winnowing-fan and broom to sweep the grain out of the grass and make their livelihood in that way.

8. Occupation.

The Bharias are usually farmservants and field-labourers, and their services in these capacities are in much request. They are hardy and industrious, and so simple that it is an easy matter for their masters to involve them in perpetual debt, and thus to keep them bound to service from generation to generation. They have no understanding of accounts, and the saying, ‘Pay for the marriage of a Bharia and he is your bond-slave for ever,’ sufficiently explains the methods adopted by their employers and creditors.

Bhāt

1. Origin of the Bhāts.

Bhāt, Rao, Jasondhi.—The caste of bards and genealogists. In 1911 the Bhāts numbered 29,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berār, being distributed over all Districts and States, with a slight preponderance in large towns such as Nāgpur, Jubbulpore and Amraoti. The name Bhāt is derived from the Sanskrit Bhatta, a lord. The origin of the Bhāts has been discussed in detail by Sir H. Risley. Some, no doubt, are derived from the Brāhman caste as stated by Mr. Nesfield: “They are an offshoot from those secularised Brāhmans who frequented the courts of princes and the camps of warriors, recited their praises in public, and kept records of their genealogies. Such, without much variation, is the function of the Bhāt at the present day. The Mahābhārata speaks of a band of bards and eulogists marching in front of Yudishthira as he made his progress from the field of Kurukshetra towards Hastinapur. But these very men are spoken of in the same poem as Brāhmans. Naturally as time went on these courtier priests became hereditary bards, receded from the parent stem and founded a new caste.” “The best modern opinion,” Sir H. Risley states,281 “seems disposed to find the germ of the Brāhman caste in the bards, ministers and family priests, who were attached to the king’s household in Vedic times. The characteristic profession of the Bhāts has an ancient and distinguished history. The literature of both Greece and India owes the preservation of its oldest treasures to the singers who recited poems in the households of the chiefs, and doubtless helped in some measure to shape the masterpieces which they handed down. Their place was one of marked distinction. In the days when writing was unknown, the man who could remember many verses was held in high honour by the tribal chief, who depended upon the memory of the bard for his personal amusement, for the record of his own and his ancestors’ prowess, and for the maintenance of the genealogy which established the purity of his descent. The bard, like the herald, was not lightly to be slain, and even Odysseus in the heat of his vengeance spares the ἀοιδός Phemius, ‘who sang among the wooers of necessity.’”282

2. Bhāts and Chārans.

There is no reason to doubt that the Birm or Baram Bhāts are an offshoot of Brāhmans, their name being merely a corruption of the term Brāhman. But the caste is a very mixed one, and another large section, the Chārans, are almost certainly derived from Rājpūts. Malcolm states that according to the fable of their origin, Mahādeo first created Bhāts to attend his lion and bull; but these could not prevent the former from killing the latter, which was a source of infinite vexation and trouble, as it compelled Mahādeo to create new ones. He therefore formed the Chāran, equally devout with the Bhāt, but of bolder spirit, and gave him in charge these favourite animals. From that time no bull was ever destroyed by the lion.283 This fable perhaps indicates that while the peaceful Bhāts were Brāhmans, the more warlike Chārans were Rājpūts. It is also said that some Rājpūts disguised themselves as bards to escape the vengeance of Parasurāma.284 The Māru Chārans intermarry with Rājpūts, and their name appears to be derived from Māru, the term for the Rājputāna desert, which is also found in Mārwār. Malcolm states285 that when the Rājpūts migrated from the banks of the Ganges to Rājputāna, their Brāhman priests did not accompany them in any numbers, and hence the Chārans arose and supplied their place. They had to understand the rites of worship, particularly of Siva and Pārvati, the favourite deities of the Rājpūts, and were taught to read and write. One class became merchants and travelled with large convoys of goods, and the others were the bards and genealogists of the Rājpūts. Their songs were in the rudest metre, and their language was the local dialect, understood by all. All this evidence shows that the Chārans were a class of Rājpūt bards.

3. Lower-class Bhāts.

But besides the Birm or Brāhman Bhāts and the Rājpūt Chārans there is another large body of the caste of mixed origin, who serve as bards of the lower castes and are probably composed to a great extent of members of these castes. These are known as the Brid-dhari or begging Bhāts. They beg from such castes as Lodhis, Telis, Kurmis, Ahīrs and so on, each caste having a separate section of Bhāts to serve it; the Bhāts of each caste take food from the members of the caste, but they also eat and intermarry with each other. Again, there are Bairāgi Bhāts who beg from Bairāgis, and keep the genealogies of the temple-priests and their successors. Yet another class are the Dasaundhis or Jasondhis, who sing songs in honour of Devi, play on musical instruments and practise astrology. These rank below the cultivating castes and sometimes admit members of such castes who have taken religious vows.

4. Social status of the caste.

The Brāhman or Birm-Bhāts form a separate subcaste, and the Rājpūts are sometimes called Rājbhāt. These wear the sacred thread, which the Brid-Bhāts and Jasondhis do not. The social status of the Bhāts appears to vary greatly. Sir H. Risley states that they rank immediately below Kāyasths, and Brāhmans will take water from their hands. The Chārans are treated by the Rājpūts with the greatest respect;286 the highest ruler rises when one of this class enters or leaves an assembly, and the Chāran is invited to eat first at a Rājpūt feast. He smokes from the same huqqa as Rājpūts, and only caste-fellows can do this, as the smoke passes through water on its way to the mouth. In past times the Chāran acted as a herald, and his person was inviolable. He was addressed as Mahārāj,287 and could sit on the Singhāsan or Lion’s Hide, the ancient term for a Rājpūt throne, as well as on the hides of the tiger, panther and black antelope. The Rājpūts held him in equal estimation with the Brāhman or perhaps even greater.288 This was because they looked to him to enshrine their heroic deeds in his songs and hand them down to posterity. His sarcastic references to a defeat in battle or any act displaying a want of courage inflamed their passions as nothing else could do. On the other hand, the Brid-Bhāts, who serve the lower castes, occupy an inferior position. This is because they beg at weddings and other feasts, and accept cooked food from members of the caste who are their clients. Such an act constitutes an admission of inferior status, and as the Bhāts eat together their position becomes equivalent to that of the lowest group among them. Thus if other Bhāts eat with the Bhāts of Telis or Kalārs, who have taken cooked food from their clients, they are all in the position of having taken food from Telis and Kalārs, a thing which only the lowest castes will do. If the Bhāt of any caste, such as the Kurmis, keeps a girl of that caste, she can be admitted into the community, which is therefore of a very mixed character. Such a caste as the Kurmis will not even take water from the hands of the Bhāts who serve them. This rule applies also where a special section of the caste itself act as bards and minstrels. Thus the Pardhāns are the bards of the Gonds, but rank below ordinary Gonds, who give them food and will not take it from them. And the Sānsias, the bards of the Jāts, and the Mirāsis, who are employed in this capacity by the lower castes generally, occupy a very inferior position, and are sometimes considered as impure.

5. Social customs.

The customs of the Bhāts resemble those of other castes of corresponding status. The higher Bhāts forbid the remarriage of widows, and expel a girl who becomes pregnant before marriage. They carry a dagger, the special emblem of the Chārans, in order to be distinguished from low-class Bhāts. The Bhāts generally display the chaur or yak-tail whisk and the chhadi or silver-plated rod on ceremonial occasions, and they worship these emblems of their calling on the principal festivals. The former is waved over the bridegroom at a wedding, and the latter is borne before him. The Brāhman Bhāts abstain from flesh of any kind and liquor, and other Bhāts usually have the same rules about food as the caste whom they serve. Brāhman Bhāts and Chārans alone wear the sacred thread. The high status sometimes assigned to this division of the caste is shown in the saying:

Age Brāhman pīchhe Bhāttāke pīchhe aur jāt,or, ‘First comes the Brāhman, then the Bhāt, and after them the other castes.’

6. The Bhāt’s business.

The business of a Bhāt in former times is thus described by Forbes:289 “When the rainy season closes and travelling becomes practicable, the bard sets off on his yearly tour from his residence in the Bhātwāra or bard’s quarter of some city or town. One by one he visits each of the Rājpūt chiefs who are his patrons, and from whom he has received portions of land or annual grants of money, timing his arrival, if possible, to suit occasions of marriage or other domestic festivals. After he has received the usual courtesies he produces the Wai, a book written in his own crabbed hieroglyphics or in those of his father, which contains the descent of the house from its founder, interspersed with many a verse or ballad, the dark sayings contained in which are chanted forth in musical cadence to a delighted audience, and are then orally interpreted by the bard with many an illustrative anecdote or tale. The Wai, however, is not merely a source for the gratification of family pride or even of love of song; it is also a record by which questions of relationship are determined when a marriage is in prospect, and disputes relating to the division of ancestral property are decided, intricate as these last necessarily are from the practice of polygamy and the rule that all the sons of a family are entitled to a share. It is the duty of the bard at each periodical visit to register the births, marriages and deaths which have taken place in the family since his last circuit, as well as to chronicle all the other events worthy of remark which have occurred to affect the fortunes of his patron; nor have we ever heard even a doubt suggested regarding the accurate, much less the honest fulfilment of this duty by the bard. The manners of the bardic tribe are very similar to those of their Rājpūt clients; their dress is nearly the same, but the bard seldom appears without the katār or dagger, a representation of which is scrawled beside his signature, and often rudely engraved upon his monumental stone, in evidence of his death in the sacred duty of trāga (suicide).”290

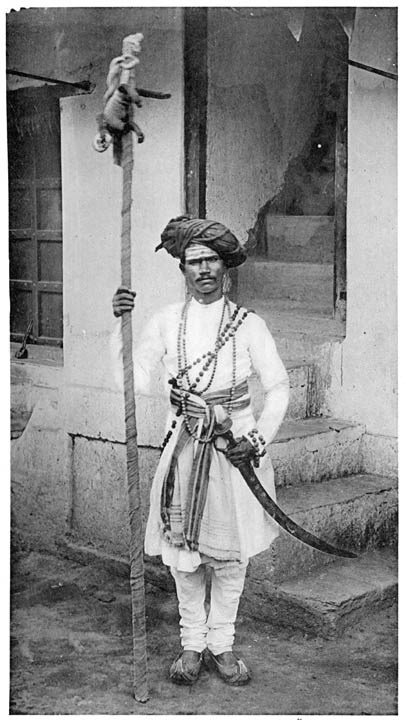

Bhāt with his putla or doll.

7. Their extortionate practices.

The Bhāt thus fulfilled a most useful function as registrar of births and marriages. But his merits were soon eclipsed by the evils produced by his custom of extolling liberal patrons and satirising those who gave inadequately. The desire of the Rājpūts to be handed down to fame in the Bhāt’s songs was such that no extravagance was spared to satisfy him. Chand, the great Rājpūt bard, sang of the marriage of Prithwi Rāj, king of Delhi, that the bride’s father emptied his coffers in gifts, but he filled them with the praises of mankind. A lakh of rupees291 was given to the chief bard, and this became a precedent for similar occasions. “Until vanity suffers itself to be controlled,” Colonel Tod wrote,292 “and the aristocratic Rājpūts submit to republican simplicity, the evils arising from nuptial profusion will not cease. Unfortunately those who should check it find their interest in stimulating it, namely, the whole crowd of māngtas or beggars, bards, minstrels, jugglers, Brāhmans, who assemble on these occasions, and pour forth their epithalamiums in praise of the virtue of liberality. The bards are the grand recorders of fame, and the volume of precedent is always resorted to by citing the liberality of former chiefs; while the dread of their satire293 shuts the eyes of the chief to consequences, and they are only anxious to maintain the reputation of their ancestors, though fraught with future ruin.” Owing to this insensate liberality in the desire to satisfy the bards and win their praises, a Rājpūt chief who had to marry a daughter was often practically ruined; and the desire to avoid such obligations led to the general practice of female infanticide, formerly so prevalent in Rājputāna. The importance of the bards increased their voracity; Mr. Nesfield describes them as “Rapacious and conceited mendicants, too proud to work but not too proud to beg.” The Dholis294 or minstrels were one of the seven great evils which the famous king Sidhrāj expelled from Anhilwāda Pātan in Gujarāt; the Dākans or witches were another.295 Malcolm states that “They give praise and fame in their songs to those who are liberal to them, while they visit those who neglect or injure them with satires in which the victims are usually reproached with illegitimate birth and meanness of character. Sometimes the Bhāt, if very seriously offended, fixes an effigy of the person he desires to degrade on a long pole and appends to it a slipper as a mark of disgrace. In such cases the song of the Bhāt records the infamy of the object of his revenge. This image usually travels the country till the party or his friends purchase the cessation of the curses and ridicule thus entailed. It is not deemed in these countries within the power of the prince, much less any other person, to stop a Bhāt or even punish him for such a proceeding. In 1812 Sevak Rām Seth, a banker of Holkar’s court, offended one of these Bhāts, pushing him rudely out of the shop where the man had come to ask alms. The man made a figure296 of him to which he attached a slipper and carried it to court, and everywhere sang the infamy of the Seth. The latter, though a man of wealth and influence, could not prevent him, but obstinately refused to purchase his forbearance. His friends after some months subscribed Rs. 80 and the Bhāt discontinued his execrations, but said it was too late, as his curses had taken effect; and the superstitious Hindus ascribe the ruin of the banker, which took place some years afterwards, to this unfortunate event.” The loquacity and importunity of the Bhāts are shown in the saying, ‘Four Bhāts make a crowd’; and their insincerity in the proverb quoted by Mr. Crooke, “The bard, the innkeeper and the harlot have no heart; they are polite when customers arrive, but neglect those leaving (after they have paid)”297 The Bhāt women are as bold, voluble and ready in retort as the men. When a Bhāt woman passes a male caste-fellow on the road, it is the latter who raises a piece of cloth to his face till the woman is out of sight.298

8. The Jasondhis.

Some of the lower classes of Bhāts have become religious mendicants and musicians, and perform ceremonial functions. Thus the Jasondhis, who are considered a class of Bhāts, take their name from the jas or hymns sung in praise of Devi. They are divided into various sections, as the Nakīb or flag-bearers in a procession, the Nāzir or ushers who introduced visitors to the Rāja, the Nagāria or players on kettle-drums, the Karaola who pour sesamum oil on their clothes and beg, and the Panda, who serve as priests of Devi, and beg carrying an image of the goddess in their hands. There is also a section of Muhammadan Bhāts who serve as bards and genealogists for Muhammadan castes. Some Bhāts, having the rare and needful qualification of literacy so that they can read the old Sanskrit medical works, have, like a number of Brāhmans, taken to the practice of medicine and are known as Kavirāj.

9. The Chārans as carriers.

As already stated, the persons of the Chārans in the capacity of bard and herald were sacred, and they travelled from court to court without fear of molestation from robbers or enemies. It seems likely that the Chārans may have united the breeding of cattle to their calling of bard; but in any case the advantage derived from their sanctity was so important that they gradually became the chief carriers and traders of Rājputāna and the adjoining tracts. They further, in virtue of their holy character, enjoyed a partial exemption from the perpetual and harassing imposts levied by every petty State on produce entering its territory; and the combination of advantages thus obtained was such as to give them almost a monopoly in trade. They carried merchandise on large droves of bullocks all over Rājputāna and the adjoining countries; and in course of time the carriers restricted themselves to their new profession, splitting off from the Chārans and forming the caste of Banjāras.

10. Suicide and the fear of ghosts.

But the mere reverence for their calling would not have sufficed for a permanent safeguard to the Chārans from destitute and unscrupulous robbers. They preserved it by the customs of Chandi or Trāga and Dharna. These consisted in their readiness to mutilate, starve or kill themselves rather than give up property entrusted to their care; and it was a general belief that their ghosts would then haunt the persons whose ill deeds had forced them to take their own lives. It seems likely that this belief in the power of a suicide or murdered man to avenge himself by haunting any persons who had injured him or been responsible for his death may have had a somewhat wide prevalence and been partly accountable for the reprobation attaching in early times to the murderer and the act of self-slaughter. The haunted murderer would be impure and would bring ill-fortune on all who had to do with him, while the injury which a suicide would inflict on his relatives in haunting them would cause this act to be regarded as a sin against one’s family and tribe. Even the ordinary fear of the ghosts of people who die in the natural course, and especially of those who are killed by accident, is so strong that a large part of the funeral rites is devoted to placating and laying the ghost of the dead man; and in India the period of observance of mourning for the dead is perhaps in reality that time during which the spirit of the dead man is supposed to haunt his old abode and render the survivors of his family impure. It was this fear of ghosts on which the Chārans relied, nor did they hesitate a moment to sacrifice their lives in defence of any obligation they had undertaken or of property committed to their care. When plunderers carried off any cattle belonging to the Chārans, the whole community would proceed to the spot where the robbers resided; and in failure of having their property restored would cut off the heads of several of their old men and women. Frequent instances occurred of a man dressing himself in cotton-quilted cloths steeped in oil which he set on fire at the bottom, and thus danced against the person against whom trāga was performed until the miserable creature dropped down and was burnt to ashes. On one occasion a Cutch chieftain, attempting to escape with his wife and child from a village, was overtaken by his enemy when about to leap a precipice; immediately turning he cut off his wife’s head with his scimitar and, flourishing his reeking blade in the face of his pursuer, denounced against him the curse of the trāga which he had so fearfully performed.299 In this case it was supposed that the wife’s ghost would haunt the enemy who had driven the husband to kill her.