полная версия

полная версияThe Posthumous Works of Thomas De Quincey, Vol. 1

10

'Postern-gate.' See the legend of Sir Eustace the Crusader, and the good Sir Hubert, who 'sounded the horn which he alone could sound,' as told by Wordsworth.

11

'The passion which made Juvenal a poet.' The scholar needs no explanation; but the reader whose scholarship is yet amongst his futurities (which I conceive to be the civilest way of describing an ignoramus) must understand that Juvenal, the Roman satirist, who was in fact a predestined poet in virtue of his ebullient heart, that boiled over once or twice a day in anger that could not be expressed upon witnessing the enormities of domestic life in Rome, was willing to forego all pretensions to natural power and inspiration for the sake of obtaining such influence as would enable him to reprove Roman vices with effect.

12

'That tamer of housemaids': Εκτορος ιπποδαμοιο—of Hector, the tamer of horses ('Iliad').

13

'On pinion of expectation.' Here I would request the reader to notice that it would have been easy for me to preserve the regular dactylic close by writing 'pinion of anticipation;' as also in the former instance of 'many a dark December' to have written 'many a rainy December.' But in both cases I preferred to lock up by the massy spondaic variety; yet never forgetting to premise a dancing dactyle—'many a'—and 'pinion of.' Not merely for variety, but for a separate effect of peculiar majesty.

14

Alluding to a ridiculous passage in Thomson's 'Seasons':

'Delightful task! to teach the young idea how to shoot.'

15

All these arts, viz., teaching the horse to fight with his forelegs or lash out with his hind-legs at various angles in a general melée of horse and foot, but especially teaching him the secret of 'inviting' an obstinate German boor to come out and take the air strapped in front of a trooper, and do his duty as guide to the imperial cavalry, were imported into the Austrian service by an English riding-master about the year 1775-80. And no doubt it must have been horses trained on this learned system of education from which the Highlanders of Scotland derived their terror of cavalry.

16

'Blind rams, brainless wild asses,' etc. The 'arietes,' or battering-rams with iron-bound foreheads, the 'onagri,' or wild asses, etc., were amongst the poliorcetic engines of the ancients, which do not appear to have received any essential improvement after the time of the brilliant Prince Demetrius, the son of Alexander's great captain, Antigonus.

17

In Mrs. Hannah More's drawing-room at Barley Wood, amongst the few pictures which adorned it, hung a kit-kat portrait of John Henderson. This, and our private knowledge that Mrs. H. M. had personally known and admired Henderson, led us to converse with that lady about him. What we gleaned from her in addition to the notices of Aguttar and of some amongst Johnson's biographers may yet see the light.

18

'Six thousand per annum,' viz., on the authority of his own confession to Pinkerton.

19

'To horsewhip,' etc. Let it not be said that this is any slander of ours; would that we could pronounce it a slander! But those who (like ourselves) have visited Ireland extensively know that the parish priest uses a horsewhip, in many circumstances, as his professional insigne.

20

Look at Lord Waterford's case, in the very month of November, 1843. Is there a county in all England that would have tamely witnessed his expulsion from amongst them by fire, and by sword and by poison?

21

One pretended proof of a decline is found in the supposed substitution of slave labour for free Italian labour. This began, it is urged, on the opening of the Nile corn trade. Unfortunately, that is a mere romance. Ovid, describing rural appearances in Italy when as yet the trade was hardly in its infancy, speaks of the rustic labourer as working in fetters. Juvenal, in an age when the trade had been vastly expanded, notices the same phenomenon almost in the same terms.

22

'The best raw material.' Some people hold that the Romans and Italians were a cowardly nation. We doubt this on the whole. Physically, however, they were inferior to their neighbours. It is certain that the Transalpine Gauls were a conspicuously taller race. Cæsar says: 'Gallis, præ magnitudine corporum quorum, brevitas nostra contemptui est' ('Bell. Gall.' 2, 30 fin.); and the Germans, in a still higher degree, were both larger men and every way more powerful. The kites, says Juvenal, had never feasted on carcases so huge as those of the Cimbri and Teutones. But this physical superiority, though great for special purposes, was not such absolutely. For the more general uses of the legionary soldier, for marching, for castrametation, and the daily labours of the spade or mattock, a lighter build was better. As to single combats, it was one effect from the Roman (as from every good) discipline—that it diminished the openings for such showy but perilous modes of contest.

23

'Any considerable portion of this provincial corn growth,' i.e., of the provincial culture which was pursued on account of Rome, meaning not the government of Rome, but, in a rigorous sense, on account of Rome the city. For here lies a great oversight of historians and economists. Because Rome, with a view to her own privileged population, i.e., the urban population of Rome, the metropolis, in order that she might support her public distributions of grain, almost of necessity depended on foreign supplies, we are not to suppose that the great mass of Italian towns and municipia did so. Maritime towns, having the benefit of ports or of convenient access, undoubtedly were participators in the Roman advantage. But inland towns would in those days have forfeited the whole difference between foreign and domestic grain by the enormous cost of inland carriage. Of canals there was but one; the rivers were not generally navigable, and ports as well as river shipping were wanting.

24

'Heraclius.' The same prosodial fault affects this name as that of Alexandria. In each name the Latin i represents a Greek ei, and in that situation (viz., as a penultimate syllable) should receive the emphasis in pronunciation as well as the sound of a long i (that sound which is heard in Longinus). So again Academia, not Academia. The Greek accentuation may be doubted, but not the Roman.

25

We have already said that Heraclius, who and whose family filled the throne of Eastern Cæsar for exactly one hundred years (611-711), consequently interesting in this way (if in no other), that he, as the reader will see by considering the limits in point of time, must have met and exhausted the first rage of the Mahometan avalanche, merits according to our estimate the title of first and noblest amongst the Oriental Cæsars. There are records or traditions of his earliest acts that we could wish otherwise. Which of us would not offend even at this day, if called upon to act under one scale of sympathies, and to be judged under another? In his own day, too painfully we say it, Heraclius could not have followed what we venture to believe the suggestions of his heart, in relation to his predecessor, because a policy had been established which made it dangerous to be merciful, and a state of public feeling which made it effeminate to pardon. First make it safe to permit a man's life, before you pronounce it ignoble to authorize his death. Strip mercy of ruin to its author, before you affirm upon a judicial punishment of death (as then it was) cruelty in the adviser or ignobility in the approver. Escaping from these painful scenes at the threshold of his public life, we find Heraclius preparing for a war, the most difficult that in any age any hero has confronted. We call him the earliest of Crusaders, because he first and literally fought for the recovery of the Cross. We call him the most prosperous of Crusaders, because he first—he last—succeeded in all that he sought, bringing back to Syria (ultimately to Constantinople) that sublime symbol of victorious Christianity which had been disgracefully lost at Jerusalem. Yet why, when comparing him not with Crusaders, but with Cæsars, do we pronounce him the noblest? Reader, which is it that is felt by a thoughtful man—supposing him called upon to select one act by preference before all others—to be the grandest act of our own Wellesley? Is it not the sagacious preparation of the lines at Torres Vedras, the self-mastery which lured the French on to their ruin, the long-suffering policy which reined up his troops till that ruin was accomplished? 'I bide my time,' was the dreadful watchword of Wellington through that great drama; in which, let us tell the French critics on Tragedy, they will find the most absolute unity of plot; for the forming of the lines as the fatal noose, the wiling back the enemy, the pursuit when the work of disorganization was perfect, all were parts of one and the same drama. If he (as another Scipio) saw another Zama, in this instance he was not our Scipio or Marcellus, but our Fabius Maximus:

26

A brutal outrage on a Captain Jenkins—i.e., cutting off his ears—was the cause of a war with Spain in the reign of George II.—Ed.

27

'The diaulos of the journey.' We recommend to the amateur in words this Greek phrase, which expresses by one word an egress linked with its corresponding regress, which indicates at once the voyage outwards and the voyage inwards, as the briefest of expressions for what is technically called 'course of post,' i.e., the reciprocation of post, its systole and diastole.

28

Wordsworth.

29

Between the forms modal, modish, and modern, the difference is of that slight order which is constantly occurring between the Elizabethan age and our own. Ish, ous, ful, some, are continually interchanging; thus, pitiful for piteous, quarrelous for quarrelsome.

30

I deny that there is or could have been one truant fluttering murmur of the heart against the reality of glory. And partly for these reasons: 1st, That, hoc abstracto, defrauding man of this, you leave him miserably bare—bare of everything. So that really and sincerely the very wisest men may be seen clinging convulsively, and clutching with their dying hands the belief that glory, that posthumous fame (which for profound ends of providence has been endowed with a subtle power of fraud such as no man can thoroughly look through; for those who, like myself, despise it most completely, cannot by any art bring forward a rationale, a theory of its hollowness that will give plenary satisfaction except to those who are already satisfied). Thus Cicero, feeling that if this were nothing, then had all his life been a skirmish, one continued skirmish for shadows and nonentities; a feeling of blank desolation, too startling—too humiliating to be faced. But (2ndly), the unsearchable hypocrisy of man, that hypocrisy which even to himself is but dimly descried, that latent hypocrisy which always does, and most profitably, possess every avenue of every man's thoughts, hence a man who should openly have avowed a doctrine that glory was a bubble, besides that, instead of being prompted to this on a principle which so far raised him above other men, must have been prompted by a principle that sank him to the level of the brutes, viz., acquiescing in total ventrine improvidence, imprescience, and selfish ease (if ease, a Pagan must have it cum dignitate), but above all he must have made proclamation that in his opinion all disinterested virtue was a chimera, since all the quadrifarious virtue of the scholastic ethics was founded either on personal self-sufficiency, on justice, moderation, etc., etc., or on direct personal and exclusive self-interest as regarded health and the elements of pleasure.

31

The tower of Siloam.

32

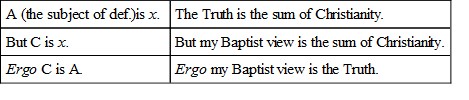

Every definition is a syllogism. Now, because the minor proposition is constantly false, this does not affect the case; each man is right to fill up the minor with his own view, and essentially they do not disagree with each other.

33

It seems that Herod made changes so vast—certainly in the surmounting works, and also probably in one place as to the foundations, that it could not be called the same Temple with that of the Captivity, except under an abuse of ideas as to matter and form, of which all nations have furnished illustrations, from the ship Argo to that of old Drake, from Sir John Cutler's stockings to the Highlander's (or Irishman's) musket.

34

Just as if a man spending his life to show the folly of Methodism should burst into maudlin tears at sight of John Wesley, and say, 'Oh, if all men, my dear brothers, were but Methodists!'

35

How so? If the Jews were naturally infidels, why did God select them? But, first, they might have, and they certainly had, other balancing qualities; secondly, in the sense here meant, all men are infidels; and we ourselves, by the very nature of one object which I will indicate, are pretty generally infidels in the same sense as they. Look at our evidences; look at the sort of means by which we often attempt to gain proselytes among the heathen and at home. Fouler infidelities there are not. Special pleading, working for a verdict, etc., etc.

36

[This idea is expanded and followed out in detail in the opening of 'Homer and the Homeridæ;' but this is evidently the note from which that grew, and is here given alike on account of its compactness and felicity.—Ed.]

37

Satire ix., lines 60, 61.

38

Who can answer a sneer?

39

Butler—'unanswerable ridicule.'

40

Said of members of the Bristol family.

41

[Born 1746, died 1800.—Ed.]