полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Nelson, Volume 2

The ten days that followed were for him, necessarily, very busy; but mental preoccupation—definiteness of object—was always beneficial to him. Even the harassing run to and from the West Indies had done him good. "I am but so-so," he had written to his brother upon arrival; "yet, what is very odd, the better for going to the West Indies, even with the anxiety." To this had succeeded the delightful fortnight at home, and now the animation and stir of expected active service. Minto had already noted his exhilaration amid the general public gloom, and after his death, speaking of these last days, said, "He was remarkably well and fresh, and full of hope and spirit." The care of providing him with adequate force he threw off upon the Admiralty. There was, of course, a consultation between him and it as to the numbers and kind of vessels he thought necessary, but his estimate was accepted without question, and the ships were promised, as far as the resources went. When Lord Barham asked him to select his own officers, he is said to have replied, "Choose yourself, my lord, the same spirit actuates the whole profession; you cannot choose wrong." He did, nevertheless, indicate his wishes in individual cases; and the expression, though characteristic enough of his proud confidence in the officers of the navy, must be taken rather as a resolve not to be burdened with invidious distinctions, than as an unqualified assertion of fact.

Nelson, however, gave one general admonition to the Cabinet which is worthy to be borne in mind, as a broad principle of unvarying application, more valuable than much labored detail. What is wanted, he said, is the annihilation of the enemy—"Only numbers can annihilate."119 It is brilliant and inspiring, indeed, to see skill and heroism bearing up against enormous odds, and even wrenching victory therefrom; but it is the business of governments to insure that such skill and heroism be more profitably employed, in utterly destroying, with superior forces, the power of the foe, and so compelling peace. No general has won more striking successes over superior numbers than did Napoleon; no ruler has been more careful to see that adequate superiority for his own forces was provided from the beginning. Nelson believed that he had fully impressed the Prime Minister that what was needed now, after two and a half years of colorless war, was not a brilliant victory for the British Navy, but a crushing defeat for the foe. "I hope my absence will not be long," he wrote to Davison, "and that I shall soon meet the combined fleets with a force sufficient to do the job well: for half a victory would but half content me. But I do not believe the Admiralty can give me a force within fifteen or sixteen sail-of-the-line of the enemy; and therefore, if every ship took her opponent, we should have to contend with a fresh fleet of fifteen or sixteen sail-of-the-line. But I will do my best; and I hope God Almighty will go with me. I have much to lose, but little to gain; and I go because it's right, and I will serve the Country faithfully." He doubtless did not know then that Calder, finding Villeneuve had gone to Cadiz, had taken thither the eighteen ships detached with him from the Brest blockade, and that Bickerton had also joined from within the Mediterranean, so that Collingwood, at the moment he was writing, had with him twenty-six of the line. His anticipation, however, was substantially correct. Despite every effort, the Admiralty up to a fortnight before Trafalgar had not given him the number of ships he thought necessary, to insure certain watching, and crushing defeat. He was particularly short of the smaller cruisers wanted.

On the 12th of September Minto took his leave of him. "I went yesterday to Merton," he wrote on the 13th, "in a great hurry, as Lord Nelson said he was to be at home all day, and he dines at half-past three. But I found he had been sent for to Carleton House, and he and Lady Hamilton did not return till half-past five." The Prince of Wales had sent an urgent command that he particularly wished to see him before he left England. "I stayed till ten at night," continues Minto, "and I took a final leave of him. He goes to Portsmouth to-night. Lady Hamilton was in tears all day yesterday, could not eat, and hardly drink, and near swooning, and all at table. It is a strange picture. She tells me nothing can be more pure and ardent than this flame." Lady Hamilton may have had the self-control of an actress, but clearly not the reticence of a well-bred woman.

On the following night Nelson left home finally. His last act before leaving the house, it is said, was to visit the bed where his child, then between four and five, was sleeping, and pray over her. The solemn anticipation of death, which from this time forward deepened more and more over his fearless spirit, as the hour of battle approached, is apparent in the record of his departure made in his private diary:—

Friday Night, September 13th.

At half-past ten drove from dear dear Merton, where I left all which I hold dear in this world, to go to serve my King and Country. May the great God whom I adore enable me to fulfil the expectations of my Country; and if it is His good pleasure that I should return, my thanks will never cease being offered up to the Throne of His Mercy. If it is His good Providence to cut short my days upon earth, I bow with the greatest submission, relying that He will protect those so dear to me, that I may leave behind. His will be done: Amen, Amen, Amen.

At six o'clock on the morning of the 14th Nelson arrived at Portsmouth. At half-past eleven his flag was again hoisted on board the "Victory," and at 2 P.M. he embarked. His youngest and favorite sister, Mrs. Matcham, with her husband, had gone to Portsmouth to see him off. As they were parting, he said to her: "Oh, Katty! that gypsy;" referring to his fortune told by a gypsy in the West Indies many years before, that he should arrive at the head of his profession by the time he was forty. "What then?" he had asked at the moment; but she replied, "I can tell you no more; the book is closed."120 The Battle of the Nile, preceding closely the completion of his fortieth year, not unnaturally recalled the prediction to mind, where the singularity of the coincidence left it impressed; and now, standing as he did on the brink of great events, with half-acknowledged foreboding weighing on his heart, he well may have yearned to know what lay beyond that silence, within the closed covers of the book of fate.

CHAPTER XXII.

THE ANTECEDENTS OF TRAFALGAR

SEPTEMBER 15—OCTOBER 19, 1805. AGE, 47The crowds that had assembled to greet Nelson's arrival at Portsmouth, four weeks before, now clustered again around his footsteps to bid him a loving farewell. Although, to avoid such demonstrations, he had chosen for his embarkation another than the usual landing-place, the multitude collected and followed him to the boat. "They pressed forward to obtain sight of his face," says Southey; "Many were in tears, and many knelt down before him, and blessed him as he passed. England has had many heroes, but never one," he justly adds, "who so entirely possessed the love of his fellow countrymen as Nelson." There attached to him not only the memory of many brilliant deeds, nor yet only the knowledge that more than any other he stood between them and harm,—his very name a tower of strength over against their enemies. The deep human sympathy which won its way to the affections of those under his command, in immediate contact with his person, seamen as well as officers, had spread from them with quick contagion throughout all ranks of men; and heart answered to heart in profound trust, among those who never had seen his face. "I had their huzzas before," he said to Captain Hardy, who sat beside him in the boat. "Now I have their hearts."

He was accompanied to the ship by Mr. Canning and Mr. Rose, intimate associates of Mr. Pitt, and they remained on board to dine. Nelson noted that just twenty-five days had been passed ashore, "from dinner to dinner." The next morning, Sunday, September 15th, at 8 A.M., the "Victory" got under way and left St. Helen's, where she had been lying at single anchor, waiting to start. Three other line-of-battle ships belonging to his fleet, and which followed him in time for Trafalgar, were then at Spithead, but not yet ready. The "Victory" therefore sailed without them, accompanied only by Blackwood's frigate, the "Euryalus." The wind outside, being west-southwest, was dead foul, and it was not till the 17th that the ship was off Plymouth. There it fell nearly calm, and she was joined by two seventy-fours from the harbor. The little squadron continued its course, the wind still ahead, until the 20th of the month, when it had not yet gained a hundred miles southwest from Scilly. Here Nelson met his former long-tried second in the Mediterranean, Sir Richard Bickerton, going home ill; having endured the protracted drudgery off Toulon only to lose, by a hair's breadth, his share in the approaching triumph.

On the 25th the "Victory" was off Lisbon. "We have had only one day's real fair wind," wrote Nelson to Lady Hamilton, "but by perseverance we have done much." The admiral sent in letters to the British consul and naval officers, urging them to secure as many men as possible for the fleet, but enjoining profound secrecy about his coming, conscious that his presence would be a deterrent to the enemy and might prevent the attempt to leave Cadiz, upon which he based his hopes of a speedy issue, and a speedy return home for needed repose. His departure from England, indeed, could not remain long unknown in Paris; but communications by land were slow in those times, and a few days' ignorance of his arrival, and of the reinforcement he brought, might induce Villeneuve to dare the hazard which he otherwise might fear. "Day by day," he wrote to Davison, "I am expecting the allied fleet to put to sea—every day, hour, and moment." "I am convinced," he tells Blackwood, who took charge of the inshore lookout, "that you estimate, as I do, the importance of not letting these rogues escape us without a fair fight, which I pant for by day, and dream of by night." For the same reasons of secrecy he sent a frigate ahead to Collingwood, with orders that, when the "Victory" appeared, not only should no salutes be fired, but no colors should be shown, if in sight of the port. The like precautions were continued when any new ship joined. Every care was taken to lull the enemy into confidence, and to lure him out of port.

At 6 P.M. of Saturday, September 28th, the "Victory" reached the fleet, then numbering twenty-nine of the line; the main body being fifteen to twenty miles west of Cadiz, with six ships close in with the port. The next day was Nelson's birthday—forty-seven years old. The junior admirals and the captains visited the commander-in chief, as customary, but with demonstrations of gladness and confidence that few leaders have elicited in equal measure from their followers. "The reception I met with on joining the fleet caused the sweetest sensation of my life. The officers who came on board to welcome my return, forgot my rank as commander-in-chief in the enthusiasm with which they greeted me. As soon as these emotions were past, I laid before them the plan I had previously arranged for attacking the enemy; and it was not only my pleasure to find it generally approved, but clearly perceived and understood." To Lady Hamilton he gave an account of this scene which differs little from the above, except in its greater vividness. "I believe my arrival was most welcome, not only to the Commander of the fleet, but also to every individual in it; and, when I came to explain to them the 'Nelson touch,' it was like an electric shock. Some shed tears, all approved—'It was new—it was singular—it was simple!' and, from admirals downwards, it was repeated—'It must succeed, if ever they will allow us to get at them! You are, my Lord, surrounded by friends whom you inspire with confidence.' Some may be Judas's: but the majority are certainly much pleased with my commanding them." No more joyful birthday levee was ever held than that of this little naval court. Besides the adoration for Nelson personally, which they shared with their countrymen in general, there mingled with the delight of the captains the sentiment of professional appreciation and confidence, and a certain relief, noticed by Codrington, from the dry, unsympathetic rule of Collingwood, a man just, conscientious, highly trained, and efficient, but self-centred, rigid, uncommunicative; one who fostered, if he did not impose, restrictions upon the intercourse between the ships, against which he had inveighed bitterly when himself one of St. Vincent's captains. Nelson, on the contrary, at once invited cordial social relations with the commanding officers. Half of the thirty-odd were summoned to dine on board the flagship the first day, and half the second. Not till the third did he permit himself the luxury of a quiet dinner chat with his old chum, the second in command, whose sterling merits, under a crusty exterior, he knew and appreciated. Codrington mentions also an incident, trivial in itself, but illustrative of that outward graciousness of manner, which, in a man of Nelson's temperament and position, is rarely the result of careful cultivation, but bespeaks rather the inner graciousness of the heart that he abundantly possessed. They had never met before, and the admiral, greeting him with his usual easy courtesy, handed him a letter from his wife, saying that being intrusted with it by a lady, he made a point of delivering it himself, instead of sending it by another.

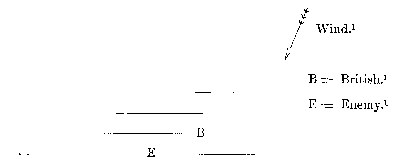

The "Nelson touch," or Plan of Attack, expounded to his captains at the first meeting, was afterwards formulated in an Order, copies of which were issued to the fleet on the 9th of October. In this "Memorandum," which was doubtless sufficient for those who had listened to the vivid oral explanation of its framer, the writer finds the simplicity, but not the absolute clearness, that they recognized. It embodies, however, the essential ideas, though not the precise method of execution, actually followed at Trafalgar, under conditions considerably different from those which Nelson probably anticipated; and it is not the least of its merits as a military conception that it could thus, with few signals and without confusion, adapt itself at a moment's notice to diverse circumstances. This great order not only reflects the ripened experience of its author, but contains also the proof of constant mental activity and development in his thought; for it differs materially in detail from the one issued a few months before to the fleet, when in pursuit of Villeneuve to the West Indies. As the final, and in the main consecutive, illustrations of his military views, the two are presented here together.

PLAN OF ATTACK.121

The business of an English Commander-in-Chief being first to bring an Enemy's Fleet to Battle, on the most advantageous terms to himself, (I mean that of laying his Ships close on board the Enemy, as expeditiously as possible;) and secondly, to continue them there, without separating, until the business is decided; I am sensible beyond this object it is not necessary that I should say a word, being fully assured that the Admirals and Captains of the Fleet I have the honour to command, will, knowing my precise object, that of a close and decisive Battle, supply any deficiency in my not making signals; which may, if extended beyond these objects, either be misunderstood, or, if waited for, very probably, from various causes, be impossible for the Commander-in-Chief to make: therefore, it will only be requisite for me to state, in as few words as possible, the various modes in which it may be necessary for me to obtain my object, on which depends, not only the honour and glory of our Country, but possibly its safety, and with it that of all Europe, from French tyranny and oppression.

Plan of Attack, issued May, 1805, Figures 1, 2, and 3

If the two Fleets are both willing to fight, but little manoeuvring is necessary; the less the better;—a day is soon lost in that business: therefore I will only suppose that the Enemy's Fleet being to leeward, standing close upon a wind on the starboard tack, and that I am nearly ahead of them, standing on the larboard tack, of course I should weather them. The weather must be supposed to be moderate; for if it be a gale of wind, the manoeuvring of both Fleets is but of little avail, and probably no decisive Action would take place with the whole Fleet. Two modes present themselves: one to stand on, just out of gunshot, until the Van-Ship of my Line would be about the centre Ship of the Enemy, then make the signal to wear together, then bear up, engage with all our force the six or five Van-Ships of the Enemy, passing, certainly, if opportunity offered, through their Line. This would prevent their bearing up, and the Action, from the known bravery and conduct of the Admirals and Captains, would certainly be decisive: the second or third Rear-Ships of the Enemy would act as they please, and our Ships would give a good account of them, should they persist in mixing with our Ships. The other mode would be, to stand under an easy but commanding sail, directly for their headmost Ship, so as to prevent the Enemy from knowing whether I should pass to leeward or windward of him. In that situation, I would make the signal to engage the Enemy to leeward, and to cut through their Fleet about the sixth Ship from the Van, passing very close; they being on a wind, and you going large, could cut their Line when you please. The Van-Ships of the Enemy would, by the time our Rear came abreast of the Van-Ship, be severely cut up, and our Van could not expect to escape damage. I would then have our Rear Ship, and every Ship in succession, wear, continue the Action with either the Van-Ship, or second Ship, as it might appear most eligible from her crippled state; and this mode pursued, I see nothing to prevent the capture of the five or six Ships of the Enemy's Van. The two or three Ships of the Enemy's Rear122 must either bear up, or wear; and, in either case, although they would be in a better plight probably than our two Van-Ships (now in the Rear) yet they would be separated, and at a distance to leeward, so as to give our Ships time to refit; and by that time, I believe, the Battle would, from the judgment of the Admiral and Captains, be over with the rest of them. Signals from these moments are useless, when every man is disposed to do his duty. The great object is for us to support each other, and to keep close to the Enemy, and to leeward of him.

If the Enemy are running away, then the only signals necessary will be, to engage the Enemy as arriving up with them; and the other ships to pass on for the second, third, &c., giving, if possible, a close fire into the Enemy in passing, taking care to give our Ships engaged notice of your intention.

MEMORANDUM.

(Secret)

Victory, off CADIZ, 9th October, 1805.

General Considerations.

Thinking it almost impossible to bring a Fleet of forty Sail of the Line into a Line of Battle in variable winds, thick weather, and other circumstances which must occur, without such a loss of time that the opportunity would probably be lost of bringing the Enemy to Battle in such a manner as to make the business decisive, I have therefore made up my mind to keep the Fleet in that position of sailing (with the exception of the First and Second in Command) that the Order of Sailing is to be the Order of Battle, placing the Fleet in two Lines of sixteen Ships each, with an Advanced Squadron of eight of the fastest sailing Two-decked Ships, which will always make, if wanted, a Line of twenty-four Sail, on whichever Line the Commander-in-Chief may direct.

Powers of Second in Command.

The Second in Command will, after my intentions are made known to him, have the entire direction of his Line to make the attack upon the Enemy, and to follow up the blow until they are captured or destroyed.

The Attack from to Leeward.

If the Enemy's Fleet should be seen to windward in Line of Battle, and that the two Lines and the Advanced Squadron can fetch them, they will probably be so extended that their Van could not succour their Rear.

I should therefore probably make the Second in Command's signal to lead through, about their twelfth Ship from their Rear, (or wherever he could fetch, if not able to get so far advanced); my Line would lead through about their Centre, and the Advanced Squadron to cut two or three or four Ships a-head of their Centre, so as to ensure getting at their Commander-in-Chief, on whom every effort must be made to capture.

The General Controlling Idea, under all Conditions.

The whole impression of the British Fleet must be to overpower from two or three Ships a-head of their Commander-in-Chief supposed to be in the Centre, to the Rear of their Fleet. I will suppose twenty Sail of the Enemy's Line to be untouched, it must be some time before they could perform a manoeuvre to bring their force compact to attack any part of the British Fleet engaged, or to succour their own Ships, which indeed would be impossible without mixing with the Ships engaged.

Something must be left to chance; nothing is sure in a Sea Fight beyond all others. Shot will carry away the masts and yards of friends as well as foes; but I look with confidence to a Victory before the Van of the Enemy could succour their Rear, and then that the British Fleet would most of them be ready to receive their twenty Sail of the Line, or to pursue them, should they endeavour to make off.

Plan of Attack for Trafalgar, Figure 1

If the Van of the Enemy tacks, the Captured Ships must run to leeward of the British Fleet; if the Enemy wears, the British must place themselves between the Enemy and the Captured, and disabled British Ships; and should the Enemy close, I have no fears as to the result.

Duties of Subordinate.

Second in Command will in all possible things direct the movements of his Line, by keeping them as compact as the nature of the circumstances will admit. Captains are to look to their particular Line as their rallying point. But, in case Signals can neither be seen or perfectly understood, no Captain can do very wrong if he places his Ship alongside that of an Enemy.

Of the intended attack from to windward, the Enemy in Line of Battle ready to receive an attack,

The Attack from to Windward.

The divisions of the British Fleet will be brought nearly within gun shot of the Enemy's Centre. The signal will most probably then be made for the Lee Line to bear up together, to set all their sails, even steering sails, in order to get as quickly as possible to the Enemy's Line, and to cut through, beginning from the 12 Ship from the Enemy's Rear. Some Ships may not get through their exact place, but they will always be at hand to assist their friends; and if any are thrown round the Rear of the Enemy, they will effectually complete the business of twelve Sail of the Enemy.

Should the Enemy wear together, or bear up and sail large, still the twelve Ships composing, in the first position, the Enemy's Rear, are to be the object of attack of the Lee Line, unless otherwise directed from the Commander-in-Chief, which is scarcely to be expected, as the entire management of the Lee Line, after the intentions of the Commander-in-Chief, is signified, is intended to be left to the judgment of the Admiral commanding that Line.

Special Charge of the Commander-in-Chief.

The remainder of the Enemy's Fleet, 34 Sail, are to be left to the management of the Commander-in-Chief, who will endeavour to take care that the movements of the Second in Command are as little interrupted as is possible.

NELSON AND BRONTE.It will be borne in mind that the first of these instructions was issued for the handling of a small body of ships—ten—expecting to meet fifteen to eighteen enemies; whereas the second contemplated the wielding of a great mass of vessels, as many as forty British, directed against a possible combination of forty-six French and Spanish. In the former case, however, although the aggregate numbers were smaller, the disproportion of force was much greater, even after allowance made for the British three-deckers; and we know, from other contemporary remarks of Nelson, that his object here was not so much a crushing defeat of the enemy—"only numbers can annihilate"—as the disorganization and neutralization of a particular detachment, as the result of which the greater combination of the enemy would fall to pieces. "After they have beaten our fleet soundly, they will do us no more harm this summer."124 Consequently, he relies much upon the confusion introduced into the enemy's movements by an attack, which, though of much inferior force, should be sudden in character, developing only at the last moment, into which the enemy should be precipitated unawares, while the British should encounter it, or rather should enter it, with minds fully prepared,—not only for the immediate manoeuvre, but for all probable consequences.