полная версия

полная версияThe Myths of the New World

By far the darkest side of such a religion is that which it presents to morality. The religious sense is by no means the voice of conscience. The Takahli Indian when sick makes a full and free confession of sins, but a murder, however unnatural and unprovoked, he does not mention, not counting it crime.440 Scenes of brutal licentiousness were approved and sustained throughout the continent as acts of worship; maidenhood was in many parts freely offered up or claimed by the priests as a right; in Central America twins were slain for religious motives; human sacrifice was common throughout the tropics, and was not unusual in higher latitudes; cannibalism was often enjoined; and in Peru, Florida, and Central America it was not uncommon for parents to slay their own children at the behest of a priest.441 The philosophical moralist, contemplating such spectacles, has thought to recognize in them one consoling trait. All history, it has been said, shows man living under an irritated God, and seeking to appease him by sacrifice of blood; the essence of all religion, it has been added, lies in that of which sacrifice is the symbol, namely, in the offering up of self, in the rendering up of our will to the will of God.442 But sacrifice, when not a token of gratitude, cannot be thus explained. It is not a rendering up, but a substitution of our will for God’s will. A deity is angered by neglect of his dues; he will revenge, certainly, terribly, we know not how or when. But as punishment is all he desires, if we punish ourselves he will be satisfied; and far better is such self-inflicted torture than a fearful looking for of judgment to come. Craven fear, not without some dim sense of the implacability of nature’s laws, is at its root. Looking only at this side of religion, the ancient philosopher averred that the gods existed solely in the apprehensions of their votaries, and the moderns have asserted that “fear is the father of religion, love her late-born daughter;”443 that “the first form of religious belief is nothing else but a horror of the unknown,” and that “no natural religion appears to have been able to develop from a germ within itself anything whatever of real advantage to civilization.”444

Far be it from me to excuse the enormities thus committed under the garb of religion, or to ignore their disastrous consequences on human progress. Yet this question is a fair one—If the natural religious belief has in it no germ of anything better, whence comes the manifest and undeniable improvement occasionally witnessed—as, for example, among the Toltecs, the Peruvians, and the Mayas? The reply is, by the influence of great men, who cultivated within themselves a purer faith, lived it in their lives, preached it successfully to their fellows, and, at their death, still survived in the memory of their nation, unforgotten models of noble qualities.445 Where, in America, is any record of such men? We are pointed, in answer, to Quetzalcoatl, Viracocha, Zamna, and their congeners. But these august figures I have shown to be wholly mythical, creations of the religious fancy, parts and parcels of the earliest religion itself. The entire theory falls to nothing, therefore, and we discover a positive side to natural religions—one that conceals a germ of endless progress, which vindicates their lofty origin, and proves that He “is not far from every one of us.”

I have already analyzed these figures under their physical aspect. Let it be observed in what antithesis they stand to most other mythological creations. Let it be remembered that they primarily correspond to the stable, the regular, the cosmical phenomena, that they are always conceived under human form, not as giants, fairies, or strange beasts; that they were said at one time to have been visible leaders of their nations, that they did not suffer death, and that, though absent, they are ever present, favoring those who remain mindful of their precepts. I touched but incidentally on their moral aspects. This was likewise in contrast to the majority of inferior deities. The worship of the latter was a tribute extorted by fear. The Indian deposits tobacco on the rocks of a rapid, that the spirit of the swift waters may not swallow his canoe; in a storm he throws overboard a dog to appease the siren of the angry waves. He used to tear the hearts from his captives to gain the favor of the god of war. He provides himself with talismans to bind hostile deities. He fees the conjurer to exorcise the demon of disease. He loves none of them, he respects none of them; he only fears their wayward tempers. They are to him mysterious, invisible, capricious goblins. But, in his highest divinity, he recognized a Father and a Preserver, a benign Intelligence, who provided for him the comforts of life—man, like himself, yet a god—God of All. “Go and do good,” was the parting injunction of his father to Michabo in Algonkin legend;446 and in their ancient and uncorrupted stories such is ever his object. “The worship of Tamu,” the culture hero of the Guaranis, says the traveller D’Orbigny, “is one of reverence, not of fear.”447 They were ideals, summing up in themselves the best traits, the most approved virtues of whole nations, and were adored in a very different spirit from other divinities.

None of them has more humane and elevated traits than Quetzalcoatl. He was represented of majestic stature and dignified demeanor. In his train came skilled artificers and men of learning. He was chaste and temperate in life, wise in council, generous of gifts, conquering rather by arts of peace than of war; delighting in music, flowers, and brilliant colors, and so averse to human sacrifices that he shut his ears with both hands when they were even mentioned.448 Such was the ideal man and supreme god of a people who even a Spanish monk of the sixteenth century felt constrained to confess were “a good people, attached to virtue, urbane and simple in social intercourse, shunning lies, skilful in arts, pious toward their gods.”449 Is it likely, is it possible, that with such a model as this before their minds, they received no benefit from it? Was not this a lever, and a mighty one, lifting the race toward civilization and a purer faith?

Transfer the field of observation to Yucatan, and we find in Zamna, to New Granada and in Nemqueteba, to Peru and in Viracocha, or his reflex Manco Capac, the lineaments of Quetzalcoatl—modified, indeed, by difference of blood and temperament, but each combining in himself all the qualities most esteemed by their several nations. Were one or all of these proved to be historical personages, still the fact remains that the primitive religious sentiment, investing them with the best attributes of humanity, dwelling on them as its models, worshipping them as gods, contained a kernel of truth potent to encourage moral excellence. But if they were mythical, then this truth was of spontaneous growth, self-developed by the growing distinctness of the idea of God, a living witness that the religious sense, like every other faculty, has within itself a power of endless evolution.

If we inquire the secret of the happier influence of this element in natural worship, it is all contained in one word—its humanity. “The Ideal of Morality,” says the contemplative Novalis, "has no more dangerous rival than the Ideal of the Greatest Strength, of the most vigorous life, the Brute Ideal” (das Thier-Ideal).450 Culture advances in proportion as man recognizes what faculties are peculiar to him as man, and devotes himself to their education. The moral value of religions can be very precisely estimated by the human or the brutal character of their gods. The worship of Quetzalcoatl in the city of Mexico was subordinate to that of lower conceptions, and consequently the more sanguinary and immoral were the rites there practised. The Algonkins, who knew no other meaning for Michabo than the Great Hare, had lost, by a false etymology, the best part of their religion.

Looking around for other standards wherewith to measure the progress of the knowledge of divinity in the New World, prayer suggests itself as one of the least deceptive. “Prayer,” to quote again the words of Novalis,451 “is in religion what thought is in philosophy. The religious sense prays, as the reason thinks.” Guizot, carrying the analysis farther, thinks that it is prompted by a painful conviction of the inability of our will to conform to the dictates of reason.452 Originally it was connected with the belief that divine caprice, not divine law, governs the universe, and that material benefits rather than spiritual gifts are to be desired. The gradual recognition of its limitations and proper objects marks religious advancement. The Lord’s Prayer contains seven petitions, only one of which is for a temporal advantage, and it the least that can be asked for. What immeasurable interval between it and the prayer of the Nootka Indian on preparing for war!—

“Great Quahootze, let me live, not be sick, find the enemy, not fear him, find him asleep, and kill a great many of him.”453

Or again, between it and the petition of a Huron to a local god, heard by Father Brebeuf:—

“Oki, thou who livest in this spot, I offer thee tobacco. Help us, save us from shipwreck, defend us from our enemies, give us a good trade, and bring us back safe and sound to our villages.”454

This is a fair specimen of the supplications of the lowest religion. Another equally authentic is given by Father Allouez.455 In 1670 he penetrated to an outlying Algonkin village, never before visited by a white man. The inhabitants, startled by his pale face and long black gown, took him for a divinity. They invited him to the council lodge, a circle of old men gathered around him, and one of them, approaching him with a double handful of tobacco, thus addressed him, the others grunting approval:—

“This, indeed, is well, Blackrobe, that thou dost visit us. Have mercy upon us. Thou art a Manito. We give thee to smoke.

“The Naudowessies and Iroquois are devouring us. Have mercy upon us.

“We are often sick; our children die; we are hungry. Have mercy upon us. Hear me, O Manito, I give thee to smoke.

“Let the earth yield us corn; the rivers give us fish; sickness not slay us; nor hunger so torment us. Hear us, O Manito, we give thee to smoke.”

In this rude but touching petition, wrung from the heart of a miserable people, nothing but their wretchedness is visible. Not the faintest trace of an aspiration for spiritual enlightenment cheers the eye of the philanthropist, not the remotest conception that through suffering we are purified can be detected.

By the side of these examples we may place the prayers of Peru and Mexico, forms composed by the priests, written out, committed to memory, and repeated at certain seasons. They are not less authentic, having been collected and translated in the first generation after the conquest. One to Viracocha Pachacamac, was as follows:—

“O Pachacamac, thou who hast existed from the beginning and shalt exist unto the end, powerful and pitiful; who createdst man by saying, let man be; who defendest us from evil and preservest our life and health; art thou in the sky or in the earth, in the clouds or in the depths? Hear the voice of him who implores thee, and grant him his petitions. Give us life everlasting, preserve us, and accept this our sacrifice.”456

In the voluminous specimens of Aztec prayers preserved by Sahagun, moral improvement, the “spiritual gift,” is very rarely if at all the object desired. Health, harvests, propitious rains, release from pain, preservation from dangers, illness, and defeat, these are the almost unvarying themes. But here and there we catch a glimpse of something better, some dim sense of the divine beauty of suffering, some feeble glimmering of the grand truth so nobly expressed by the poet:—

aus des Busens Tiefe strömt GedeihnDer festen Duldung und entschlossner That.Nicht Schmerz ist Unglück, Glück nicht immer Freude;Wer sein Geschick erfüllt, dem lächeln beide.“Is it possible,” says one of them, “that this scourge, this affliction, is sent to us not for our correction and improvement, but for our destruction and annihilation? O Merciful Lord, let this chastisement with which thou hast visited us, thy people, be as those which a father or mother inflicts on their children, not out of anger, but to the end that they may be free from follies and vices.” Another formula, used when a chief was elected to some important position, reads: “O Lord, open his eyes and give him light, sharpen his ears and give him understanding, not that he may use them to his own advantage, but for the good of the people he rules. Lead him to know and to do thy will, let him be as a trumpet which sounds thy words. Keep him from the commission of injustice and oppression.”457

At first, good and evil are identical with pleasure and pain, luck and ill-luck. “The good are good warriors and hunters,” said a Pawnee chief,458 which would also be the opinion of a wolf, if he could express it. Gradually the eyes of the mind are opened, and it is perceived that “whom He loveth, He chastiseth,” and physical give place to moral ideas of good and evil. Finally, as the idea of God rises more distinctly before the soul, as “the One by whom, in whom, and through whom all things are,” evil is seen to be the negation, not the opposite of good, and itself “a porch oft opening on the sun.”

The influence of these religions on art, science, and social life, must also be weighed in estimating their value.

Nearly all the remains of American plastic art, sculpture, and painting, were obviously designed for religious purposes. Idols of stone, wood, or baked clay, were found in every Indian tribe, without exception, so far as I can judge; and in only a few directions do these arts seem to have been applied to secular purposes. The most ambitious attempts of architecture, it is plain, were inspired by religious fervor. The great pyramid of Cholula, the enormous mounds of the Mississippi valley, the elaborate edifices on artificial hills in Yucatan, were miniature representations of the mountains hallowed by tradition, the “Hill of Heaven,” the peak on which their ancestors escaped in the flood, or that in the terrestrial paradise from which flow the rains. Their construction took men away from war and the chase, encouraged agriculture, peace, and a settled disposition, and fostered the love of property, of country, and of the gods. The priests were also close observers of nature, and were the first to discover its simpler laws. The Aztec sages were as devoted star-gazers as the Chaldeans, and their calendar bears unmistakable marks of native growth, and of its original purpose to fix the annual festivals. Writing by means of pictures and symbols was cultivated chiefly for religious ends, and the word hieroglyph is a witness that the phonetic alphabet was discovered under the stimulus of the religious sentiment. Most of the aboriginal literature was composed and taught by the priests, and most of it refers to matters connected with their superstitions. As the gifts of votaries and the erection of temples enriched the sacerdotal order individually and collectively, the terrors of religion were lent to the secular arm to enforce the rights of property. Music, poetic, scenic, and historical recitations, formed parts of the ceremonies of the more civilized nations, and national unity was strengthened by a common shrine. An active barter in amulets, lucky stones, and charms, existed all over the continent, to a much greater extent than we might think. As experience demonstrates that nothing so efficiently promotes civilization as the free and peaceful intercourse of man with man, I lay particular stress on the common custom of making pilgrimages.

The temple on the island of Cozumel in Yucatan was visited every year by such multitudes from all parts of the peninsula, that roads, paved with cut stones, had been constructed from the neighboring shore to the principal cities of the interior.459 Each village of the Muyscas is said to have had a beaten path to Lake Guatavita, so numerous were the devotees who journeyed to the shrine there located.460 In Peru the temples of Pachacamà, Rimac, and other famous gods, were repaired to by countless numbers from all parts of the realm, and from other provinces within a radius of three hundred leagues around. Houses of entertainment were established on all the principal roads, and near the temples, for their accommodation; and when they made known the object of their journey, they were allowed a safe passage even through an enemy’s territory.461

The more carefully we study history, the more important in our eyes will become the religious sense. It is almost the only faculty peculiar to man. It concerns him nearer than aught else. It is the key to his origin and destiny. As such it merits in all its developments the most earnest attention, an attention we shall find well repaid in the clearer conceptions we thus obtain of the forces which control the actions and fates of individuals and nations.

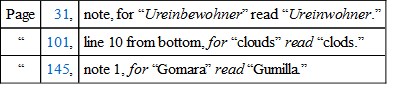

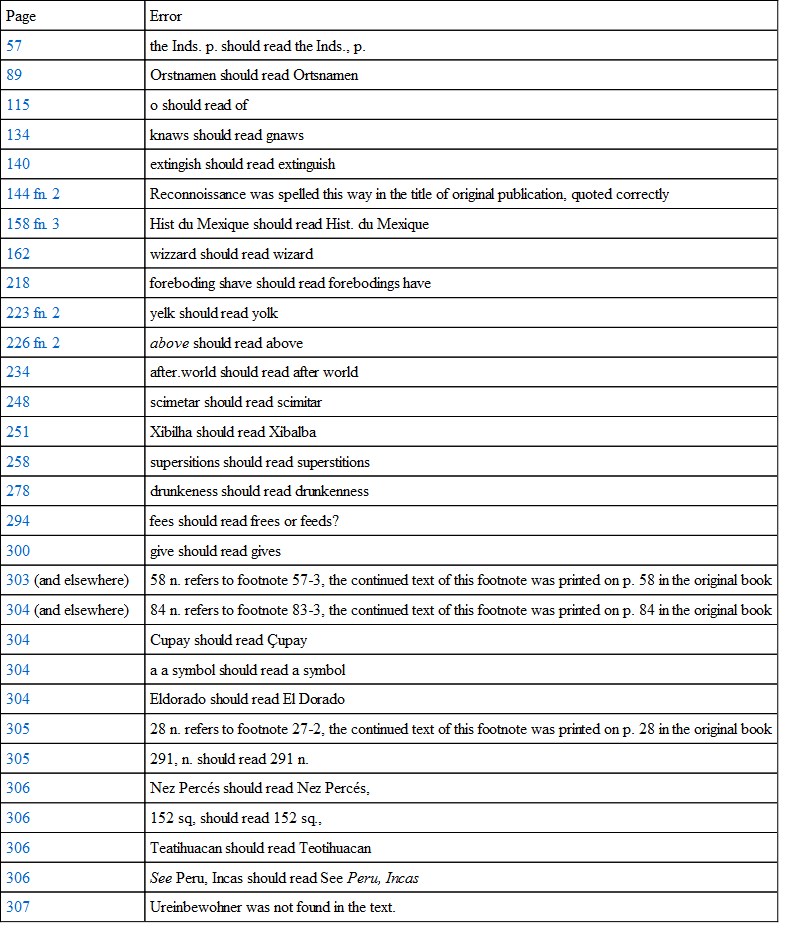

ERRATA

The following errors and inconsistencies have been maintained.

Misspelled words and typographical errors:

The following words had inconsistent spelling:

Mannacicas / Mannicicas

rôle / role

Quiché / Quiche

Tamöi / Tamoi

The following words had inconsistent hyphenation:

Aka-kanet / Akakanet

Ama-livaca / Amalivaca

child-birth / childbirth

Teo-tihuacan / Teotihuacan

under-world / underworld

Ur-religionen / Urreligionen

Yoalli-ehecatl / Yoalliehecatl

Other inconsistencies:

Titles of works referred to in the footnotes are occasionally not italicized. Author names of the works referred to in the footnotes are occasionally italicized.

1

Waitz, Anthropologie der Naturvoelker, i. p. 256.

2

Carriere, Die Kunst im Zusammenhang der Culturentwickelung, i. p. 66.

3

It is said indeed that the Yebus, a people on the west coast of Africa, speak a polysynthetic language, and per contra, that the Otomis of Mexico have a monosyllabic one like the Chinese. Max Mueller goes further, and asserts that what is called the process of agglutination in the Turanian languages is the same as what has been named polysynthesis in America. This is not to be conceded. In the former the root is unchangeable, the formative elements follow it, and prefixes are not used; in the latter prefixes are common, and the formative elements are blended with the root, both undergoing changes of structure. Very important differences.

4

Grimm, Geschichte der Deutschen Sprache, p. 571.

5

Peter Martyr, De Insulis nuper Repertis, p. 354: Colon. 1574.

6

They may be found in Waitz, Anthrop. der Naturvoelker, iv. p. 173.

7

The only authority is Diego de Landa, Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan, ed. Brasseur, Paris, 1864, p. 318. The explanation is extremely obscure in the original. I have given it in the only sense in which the author’s words seem to have any meaning.

8

Humboldt, Vues des Cordillères, p. 72.

9

Desjardins, Le Pérou avant la Conquête Espagnole, p. 122: Paris, 1858.

10

An instance is given by Ximenes, Origen de los Indios de Guatemala, p. 186: Vienna, 1856.

11

George Copway, Traditional History of the Ojibway Nation, p. 130: London, 1850.

12

Morse, Report on the Indian Tribes, App. p. 352.

13

Gomara states that De Ayllon found tribes on the Atlantic shore not far from Cape Hatteras keeping flocks of deer (ciervos) and from their milk making cheese (Hist. de las Indias, cap. 43). I attach no importance to this statement, and only mention it to connect it with some other curious notices of the tribe now extinct who occupied that locality. Both De Ayllon and Lawson mention their very light complexions, and the latter saw many with blonde hair, blue eyes, and a fair skin; they cultivated when first visited the potato (or the groundnut), tobacco, and cotton (Humboldt); they reckoned time by disks of wood divided into sixty segments (Lederer); and just in this latitude the most careful determination fixes the mysterious White-man’s-land, or Great Ireland of the Icelandic Sagas (see the American Hist. Mag., ix. p. 364), where the Scandinavian sea rovers in the eleventh century found men of their own color, clothed in long woven garments, and not less civilized than themselves.

14

The name Eskimo is from the Algonkin word Eskimantick, eaters of raw flesh. There is reason to believe that at one time they possessed the Atlantic coast considerably to the south. The Northmen, in the year 1000, found the natives of Vinland, probably near Rhode Island, of the same race as they were familiar with in Labrador. They call them Skralingar, chips, and describe them as numerous and short of stature (Eric Rothens Saga, in Mueller, Sagænbibliothek, p. 214). It is curious that the traditions of the Tuscaroras, who placed their arrival on the Virginian coast about 1300, spoke of the race they found there as eaters of raw flesh and ignorant of maize (Lederer, Account of North America, in Harris, Voyages).

15

Richardson, Arctic Expedition, p. 374.

16

The late Professor W. W. Turner of Washington, and Professor Buschmann of Berlin, are the two scholars who have traced the boundaries of this widely dispersed family. The name is drawn from Lake Athapasca in British America.

17

The Cherokee tongue has a limited number of words in common with the Iroquois, and its structural similarity is close. The name is of unknown origin. It should doubtless be spelled Tsalakie, a plural form, almost the same as that of the river Tellico, properly Tsaliko (Ramsey, Annals of Tennessee, p. 87), on the banks of which their principal towns were situated. Adair’s derivation from cheera, fire, is worthless, as no such word exists in their language.

18

The term Algonkin may be a corruption of agomeegwin, people of the other shore. Algic, often used synonymously, is an adjective manufactured by Mr. Schoolcraft “from the words Alleghany and Atlantic” (Algic Researches, ii. p. 12). There is no occasion to accept it, as there is no objection to employing Algonkin both as substantive and adjective. Iroquois is a French compound of the native words hiro, I have said, and kouè, an interjection of assent or applause, terms constantly heard in their councils.

19

Apalachian, which should be spelt with one p, is formed of two Creek words, apala, the great sea, the ocean, and the suffix chi, people, and means those dwelling by the ocean. That the Natchez were offshoots of the Mayas I was the first to surmise and to prove by a careful comparison of one hundred Natchez words with their equivalents in the Maya dialects. Of these, five have affinities more or less marked to words peculiar to the Huastecas of the river Panuco (a Maya colony), thirteen to words common to Huasteca and Maya, and thirty-nine to words of similar meaning in the latter language. This resemblance may be exemplified by the numerals, one, two, four, seven, eight, twenty. In Natchez they are hu, ah, gan, uk-woh, upku-tepish, oka-poo: in Maya, hu, ca, can, uk, uapxæ, hunkal. (See the Am. Hist. Mag., New Series, vol. i. p. 16, Jan. 1867.)

20

Dakota, a native word, means friends or allies.